Children as Levels: Early Understandings of Reading Development Conceptualized by Preservice Teachers

Andrea Fraser, Mount St. Vincent University

Author’s Note

Andrea Fraser https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5288-1685

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Andrea Fraser at andrea.fraser10@msvu.ca

Abstract

This qualitative study surfaced beliefs around reading instruction and reading development at the onset of an elementary literacy methods course. Prior understandings and knowledge around reading instruction and reading acquisition emerge through various experiences and have the potential to contradict notions presented by teacher educators. This inquiry explored prior beliefs held by five preservice teachers (PSTs) about the nature of reading and the teaching of reading, drawing on a thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) of a pre-course survey. Results indicated that early understandings of reading development and pedagogy appear to rely on levelling systems for assessing and identifying students’ acquisition of reading skills, as well as organizing students into levels for instruction. Beliefs that reading development progresses through a levelled gradient are problematic for both teacher and student, shifting attention away from the complex nature of reading acquisition and the skills required to develop proficiency. While no generalizable statement can be made regarding PSTs’ most frequently held beliefs, this pilot study puts forward the idea that understanding PSTs’ prior beliefs is a critical part of teacher education. Intentional opportunities to unpack prior beliefs and understandings may offer insight for teacher educators to engage students in discourse and experience cognitive dissonance around inconsistencies, making space for learning and unlearning.

Keywords: preservice teachers, teacher education, levels, reading, reading assessment

Children as Levels: Early Understandings of Reading Development Conceptualized by Preservice Teachers

The impact of beliefs and prior assumptions about reading acquisition and development cannot be underestimated. Instructional decisions and designs are often influenced by belief systems held by teachers (Bryan, 2003; Richardson et al., 1991; Skott, 2014), and the relationship between instruction and student achievement is well-researched (Otaiba et al., 2016; Darling-Hammond, 1996, 2000; Guerriero, 2017; International Literacy Association, 2018; Muñoz et al., 2011; Rivkin et al., 2005; Wright et al., 1997). Given that instructional decisions are often grounded in teacher beliefs and that student achievement is directly linked to instructional approach, it is therefore critical to examine how teachers form foundational beliefs regarding all aspects of learning, instruction, and pedagogy.

In a 2000 analysis of state policy surveys and case study data, Darling-Hammond suggests that variables related to teacher quality, such as teacher preparation, certification, and a major in the content area, are more influential in predicting student achievement levels than factors including class size, heterogeneity, poverty, and language status. The focus of teacher education is, therefore, a significant variable in determining teacher efficacy. For example, in reading instruction, Piasta et al. (2009) consider the relationship between teachers’ code-related knowledge, explicit decoding instruction, and word reading gains of grade one students. Their findings suggest that teacher knowledge of code-related skills, as demonstrated in the Teacher Knowledge Assessment: Language and Print assessment (Piasta et al., 2009), is positively related to reading gains. Interestingly, despite the use of a highly scripted core curriculum, the students receiving instruction from teachers with lower scores on the Teacher Knowledge Assessment had weaker reading gains. The authors of this study highlight that the use of a core curriculum may provide an instructional base but suggest that specialized knowledge of language and literacy offers teachers the skills to approach instruction flexibly to address the individual needs of students. They suggest that when teachers have specialized knowledge, they are better able to interpret and respond to student errors, engage students in appropriate material for instruction and practice outside the scripted curricula, and adapt the pacing, intensity, and sequence of the curricula to meet the needs of the students. Given the importance of teachers’ underlying beliefs about education and content knowledge, teacher educators must be attentive to preservice teachers’ learning and unlearning processes. The area of reading is one key area where the need for this dual approach is readily apparent.

Approximately 40% of students learn to read with relative ease (Hempenstall, 2016; Lyon, 1998; State Collaborative on Reforming Education, 2020; Young, 2017). However, many find it considerably difficult, and this level of difficulty is compounded by intersectional factors: students navigating poverty, students who identify as racial minorities or as English language learners, and students with disabilities are at increased risk (Fien et al., 2021; Snow et al., 1998). This is not to suggest that students who find learning to read difficult have a disability. Studies demonstrate that most children can learn to read proficiently when provided explicit instruction and targeted intervention, when necessary, of foundational reading skills (Lesaux & Siegel, 2003; Otaiba & Torgesen, 2007; Savage et al., 2018).

Data reported by Saskatchewan's Ministry of Education (2024) demonstrates a persistent gap in reading achievement between Indigenous and non-indigenous students. Reading data outlined in the Ministry of Education 2023-24 annual report reflected that in the 2022-23 school year, 70% of Grade 3 students achieved the provincially developed grade-level benchmarks using the approved levelled reading assessments (Saskatchewan Ministry of Education, 2021), while the percentage of self-identified First Nations, Inuit, and Métis students who achieved this level of proficiency was reported at 45.5%. This disparity in reading achievement has been reported consistently from 2014 through 2023 (Saskatchewan Ministry of Education, 2020; Saskatchewan Ministry of Education, 2024). Despite provincial efforts through education sector strategic plans (Government of Saskatchewan, 2014; Ministry of Education, n.d.), literacy rates in Saskatchewan continue to remain below the 80% at or above grade level target set by the province, and Indigenous students continue to perform below their peers, highlighting issues related to equity.

The Ontario Human Rights Commission’s (2022) Right to Read inquiry report addressed issues related to equity. They suggested that families from historically marginalized backgrounds may not have the access or financial resources to navigate the system or obtain reading support services outside of the school system. The OHRC report calls on faculties of education to promote the goal of equity through the broader topic of culturally responsive instruction, defined by Hammond (2020) as educational practices focused on the cognitive development of under-served students alongside the development of a deeper understanding of scientifically supported pedagogy. It should be noted that culturally responsive pedagogy is not reflected through a distinct routine or program but rather “shaped by the sociocultural characteristics of the settings in which they occur, and the populations for whom they are designed” (Gay, 2013, p. 63) and, while important, are beyond the scope of this article. Rather, this article examines the specific orientation towards reading instruction—balanced literacy—and specific themes related to levelling that should be addressed in literacy methods courses as an act of learning and unlearning.

Literacy is recognized as a human right (Derby & Ranginui, 2018; OHRC, 2022; UNESCO, 2019) and attention to how early reading is taught in schools is influencing state legislature in the United States (Neuman et al., 2023) and has prompted inquiries by provincial human rights commissions in Saskatchewan and Ontario. There is a long history of the debate centred around how reading skills develop and, therefore, how reading should be taught. Known as the “reading wars” (Castles et al., 2018), exchanges centre around instructional approaches favouring a code-based approach—where letter and sound relationships are explicitly and systematically taught (Adams, 1991; Chall, 1967, 1983)—and a meaning-centred approach where students are encouraged to draw on oral language skills to recognize unfamiliar words (Goodman, 1970). The term balanced literacy is often used to exemplify an instructional approach that combines skill and meaning (Pressley et al., 2002) and many provincial curricula (see, British Columbia, 2016; Manitoba, 2019; Saskatchewan, 2010) reflect tenets of this approach where skill instruction is to be embedded within meaningful contexts and inquiry learning. Included in this approach is the use of levelled texts for assessment and instruction. Children are ascribed an instructional level based on a combined accuracy and comprehension score with the purpose of matching text difficulty to the reader, then using the levels to create instructional groupings of students (Pratt & Urbanowski, 2015). However, studies have called into question the reliability of commercially produced levelled reading assessments (Parker et al., 2015), the text complexity within and between levels (Burns et al., 2015; Pitcher & Fang, 2007), and the notion of instructional levels (Burns et al., 2015).

The three cueing system is another feature of a balanced approach to literacy instruction and is predicated on the notion that skilled reading draws on three information sources—semantic, syntactic, and graphophonic—represented in decreasing order of importance (Hempenstall, 2006). Semantic cues utilize the meaning of the surrounding text to assist with decoding unknown words, and syntactic cues consider the grammatical structure of the sentence wherein unknown words may be guessed based on grammatical rules. Graphophonic cues refer to the correspondence between sounds and symbols, and students may be encouraged to look at the first letter when approaching an unknown word or confirming a word choice (Hempenstall, 2006). In this approach, accurate word reading is not necessary if the meaning of the text is retained (Hempenstall, 2006). Goodman (1970) characterized reading as a “psycholinguistic guessing game” (p. 127) in which readers use graphic, semantic, and syntactic knowledge to guess the meaning of printed words. However, research indicates that accurate word identification based on contextual cues is limited (Gough et al., 1981) and that skilled readers, although attentive to the use of context to derive meaning from unfamiliar words, rely on word structure for decoding (Tunmer & Hoover, 1993). As indicated by the tension between research-informed practices and policies around reading instruction dominant in curricular design, the subject of reading instruction requires thoughtful consideration in teacher education instruction.

The reports from the Ontario Human Rights Commission (2022) and Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission (2023) call for changes in provincial curricula to align with scientific evidence for reading instruction. References to reading levels and three cueing are prevalent in the Saskatchewan English Language Arts (2010) curriculum. For example, a Grade 1 indicator that supports the outcome of reading and comprehending grade-appropriate texts is that students read aloud any text that is familiar and at an independent reading level. For the same outcome, another indicator is that students will use applicable pragmatic, textual, syntactic, semantic/lexical/morphological, graphophonic, and other communication cues and conventions to construct and communicate meaning when reading. Several provinces, such as Ontario, Alberta, and New Brunswick, have made shifts to curricular models that reflect a scientific evidence base, thus signalling a move away from levelled frameworks for reading assessment.

There has been an increase in calls for teacher education programs to prepare teacher candidates better to be teachers of reading. The Ontario Human Rights Commission's (2022) Right to Read inquiry report included six recommendations for higher education, drawing attention to the content of required literacy methods courses, the administration and use of valid assessment tools, and supporting students with exceptionalities—including students who struggle with reading and writing. In a recent review of nearly 700 elementary teacher education programs in the United States, the National Council on Teacher Quality (2023) reported that only 25% of programs adequately addressed the essential components for reading instruction (as identified in the National Reading Panel, 2000), and 40% of programs focused on content and instructional methods deemed contrary to the relevant research-base. Recommendations in this report call for critical examinations and revisions to methods courses to align with compelling research and understandings around reading instruction, as well as continued training and professional learning opportunities for the instructors of these courses.

Moats (2014) poses critical questions about the design and content of literacy methods courses that teacher education programs should consider in preparing preservice teachers with the knowledge and skills necessary to address the range of individual aptitudes for reading and includes the importance of surfacing beliefs held by PSTs and challenging those, if necessary, “in ways that engender cognitive shifts” (p. 88). Often overlooked when considering the efficacy of literacy methods courses are the beliefs about literacy pedagogy and content that preservice teachers approach coursework and learning with (Ciampa & Gallagher, 2018). Although some studies suggest that new knowledge presented in methods courses is resisted by PSTs when it contradicts personal beliefs (Clift & Brady, 2009; Massey, 2010), there is evidence that supports methods courses as avenues for negotiated understandings (Brodeur & Ortmann, 2018; Duffy & Atkinson, 2001; Leko & Mundy, 2011; Nierstheimer et al., 2000).

Kagan (1992) stressed the central role of pre-existing beliefs held by preservice and beginning teachers and concluded that beginning teachers are strongly influenced by their experiences as learners. Their pre-existing beliefs filtered the content of coursework, remained relatively unchanged, and were translated into classroom practice. Hence, beliefs may act as a barrier to new or conflicting beliefs (Risko et al., 2008) and serve as a filter to either accept or reject knowledge presented in reading methods courses (Vieira, 2019). As such, how do pedagogical decisions rooted in teachers’ beliefs influence students’ development and proficiency in reading—particularly those with increased risk factors and intersectional factors such as developmental language disorders (Snowling et al., 2021) and poverty (Buckingham et al., 2013)—when those beliefs run counter to research-informed understandings about reading? Taking this broader question into account, this paper explores the early understandings related to levelling systems to consider the narrower question: What particular beliefs, held early in a required literacy methods course, do preservice teachers surface about reading development and reading instruction?

Learning to read is one of the most complex skills students will acquire (Liu et al., 2016) as the act of reading is comprised of many skills and described by Dr. G. Reid Lyon (2003) as “one of the most complex, unnatural cognitive interactions that brain and environment have to coalesce together to produce” (para. 51). Teaching children to read is also complex and requires knowledge and skills across components of word recognition, language comprehension, spelling, and writing (Moats, 2020). However, research suggests that preservice and in-service teachers lack the depth of knowledge required to teach reading effectively, particularly to those children at risk for reading difficulties (Bos et al., 2001; CLLRN, 2009; Cheesman et al., 2010; Cohen et al., 2016; Cunningham et al., 2004; Lyon & Weiser, 2009; McCutchen et al., 2002; Meeks & Kemp, 2017; Meeks et al., 2016; Moats, 1994, 2009; Moats & Foorman, 2003; Moore, 2020; Piasta et al., 2009; Stark et al., 2016). Across Canada, changes in provincial curricula reflect current calls to align content and instruction with compelling scientific research. Literacy methods courses can help PSTs unpack their own histories and beliefs about reading acquisition and help them navigate politically charged discourses around reading by focusing on evidence-based practices while critically examining their own orientations.

Unlike many other professions, PSTs in teacher education programs bring vast classroom experiences, albeit as students. Findings from Debreli (2016), Smagorisnky and Barnes (2014), and Vieira (2019) suggest that instructional choices and learning experiences made by teachers early in their careers are primarily influenced by the experiences they enjoyed or did not enjoy as students. Accumulated and internalized beliefs about reading may also begin with literacy experiences in the home, through parent modelling, encouraged reading habits, and the ease at which an individual learns to read (Vieira, 2019). Findings by Gregoire (2003) and, more recently, Vieira (2019) highlighted the obstinate nature of beliefs whereby prior understandings served to filter the new learning presented in literacy methods courses.

Bandura (1986) suggests that beliefs may be more prone to modification in early learning experiences. As such, teacher education programs can, in fact, serve as a catalyst for shifting misaligned or outdated beliefs held by PSTs. Contrary to findings that indicated minimal shifts in understandings held by PSTs, several studies demonstrated negotiated beliefs when offered new learning in methods courses (Brodeur & Ortmann, 2018; Duffy & Atkinson, 2001; Leko & Mundy, 2011; Nierstheimer et al., 2000), highlighting the value of surfacing and interrogating beliefs and focusing on meaningful, integrated opportunities for new learning (Yost et al., 2000).

Through a social constructivist lens, this inquiry investigated the early understandings and beliefs about reading development and instruction, constructed through prior experiences, brought forward by PSTs into their first required literacy course in their teacher education program. Social constructivism is positioned on the belief that knowledge is a social construct fashioned through the interconnectedness between environment, individual, and others (Azzarito & Ennis, 2003; Olson, 1995; Vygotsky, 1978; Young & Collin, 2004). Distinctive of a social constructivist lens is the essential role of groups in constructing knowledge through collaboration, questioning, and discussions among peers with the guidance of a mentor (Yost et al., 2000). New knowledge is socially constructed and filtered through existing knowledge, creating space for revision and reconstruction of existing beliefs (Andrew et al., 2018). This inquiry sought to create space to surface initial beliefs and understandings about reading development and instruction so that they can subsequently be critically engaged. This paper accordingly presents one method through which those initial beliefs can be brought forward.

This study aimed to investigate the early understandings and knowledge of reading development and reading instruction that preservice teachers (n=5) brought with them to a required literacy methods course, guided by the research question: What particular beliefs, held early in a required literacy methods course, do preservice teachers surface about reading development and reading instruction? This study was a pilot for research completed as part of a doctoral program dissertation (Dunk, 2021). The findings from this study may serve as a catalyst for teacher educators to consider the relevance of and how to create intentional opportunities to unpack and confront prior understandings and beliefs about teaching and learning held by PSTs.

This study examines the beliefs and understandings about reading shared by participants and interpreted by the researcher. Hence, an interpretive case study design (Merriam, 1988) was suited to this study as data were collected to capture individual perspectives, which were interpreted by the researcher (Lincoln et al., 2018). Case study research has a place in investigating various aspects of teacher education programs as it can shift attention “from a ‘macro’ level encompassing broad issues of content, standards, and other program components to a ‘micro’ level for a close, in-depth look at issues that affect learning” (Maloch et al., 2003, p. 434, emphasis in original). This study examined the realities presented by the participants at a moment in time and invites readers to consider participant perspectives alongside their own knowledge, beliefs, and experiences (Merriam, 2009).

This study took place at a Canadian university where all students in the College of Education must take a literacy methods course grounded in the principle that every teacher is a teacher of reading. It is offered in students' first semester of their Bachelor of Education program. As such, it is the first literacy methods course that PSTs take in their teacher education program and is therefore well-situated as a space within which PSTs might examine their foundational beliefs prior to instructional intervention. Participants from two sections of this course were invited to participate in this study, which involved completing an online survey.

I came to this research with my own lived experiences, both personally and professionally, as do all researchers. As a classroom teacher who spent many years teaching children to read, I have lived the shifting landscape of ‘trends’ and approaches to reading instruction, often influenced by professional learning offered by the system and schools I worked with and the curricular resources provided to me for instructional use. I have had to learn, unlearn, and relearn, question my own practices, and consider how my own knowledge and approaches to instruction may be hindering the reading development of some students and what I need to do to ensure I am supporting all children as they learn to read. Through that process, I humbly come to my work as a teacher educator and researcher with the belief that ‘when we know better, we do better’ (Angelou, 2012).

Effective teachers are critical in supporting students' reading development, particularly those for whom learning to read is challenging. These teachers know when and how to adjust instruction to respond to the varied needs of students and ensure that instructional decisions are grounded in compelling evidence rather than philosophical beliefs. Teacher education programs play an essential role in developing the knowledge and experiences necessary for PSTs to be highly effective teachers of reading. This work is guided by the foundational view that all teachers, regardless of grade level or subject-area specialty, are teachers of reading (Draper, 2008; Fang, 2012; Shanahan & Shanahan, 2008). This has deeply influenced my own views on reading pedagogy and reading development.

Interpretations of the data shared by participants were constructed through the perspectives I brought forward to the study. Situated within a social constructivist lens, my role as a researcher can be described as a co-constructor of knowledge through interactions with the data. However, the participants remained the centre of the inquiry, and it is through their contributions of individual perspectives that truth emerged from a shared consensus between all constructors. These truths, or subjective human realities, reflect individual understandings of reality through one’s perspective (Erlingsson & Brysiewicz, 2013).

Following REB ethics approval, recruitment for the study took place early in the fall semester of 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, and at this time, courses transitioned from in-person to online. Consent was obtained from the instructors of two sections of a literacy methods course. The researcher shared information about the study via a virtual presentation for each section, and instructors were absent during this online recruitment presentation. Students were made aware that instructors would not be privy to who participated in the study. The researcher shared a recruitment poster with the instructors to distribute to the students enrolled in the course. This poster included a link to the online survey used to collect data for this study. Five participants across the two courses engaged in the study through this process. Participant consent was embedded in the survey, indicating the conditions of participation and that free and informed consent was implied through survey completion and submission. Participants chose a pseudonym for identification; the researcher did not know their real identities.

Fundamental to social constructivism is the recognition of social and cultural influences on learning (Adams, 2006), and it is understood that beliefs about reading development and pedagogy have accumulated and formed through various lived experiences. Although the participants in this study were enrolled in their first required course focused on literacy, they were asked on the survey if they had experience working with children learning to read (see Appendix, question 30). For context, Table 1 outlines the participants and their relevant experience. Highlighting these experiences is not presented with the intent to suggest causal or correlational connections to the findings in this study. Instead, it is to acknowledge that PSTs bring established beliefs and understandings constructed through lived experiences, some of which may be indicated here, to initial coursework in their teacher education programs.

|

Participant |

Experience |

|

Marie |

Special needs worker; EA in general and specialized classrooms; work with ELL students in various grades

|

|

Pam |

Daughter who struggled with learning to read |

|

Elizabeth Marie |

Tutor for a Grade 4 student in English |

|

Rae |

Tutor for a student with a learning disability |

|

Candace |

Parent, EA, volunteer for a city organization |

A PhD candidate conducted this research as part of a more extensive study examining the early and negotiated understandings of reading development and instruction pre- and post- a required literacy methods course. All students enrolled in the required literacy methods course were invited to participate. As this course was offered early in the teacher education program, information provided on the survey was based on the participants' experiences and reading knowledge before engaging in any other required literacy methods courses. Participants were five teacher candidates invited from two sections of the same literacy course who completed a pre-course semi-structured survey (see Appendix for survey questions). The survey was created using SurveyMonkey and hosted on the university platform. Participant access to the survey was included via a link on the recruitment poster, and all surveys were completed within one month of the start of the semester.

The pre-course survey utilized in this study was adapted from an original instrument created to track teacher beliefs related to literacy teaching by Gove (1983) and Vacca et al. (1991) and used in subsequent studies by Brenna and Dunk (2018, 2019). This survey was used to collect data on participant accounts of reading-related beliefs and knowledge and was administered and collected by the researcher.

Survey data were coded following the thematic analysis phases outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006), which served as a fitting method to report participants' shared experiences and realities (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Based on the repeated readings of the survey results, ideas resonated under the following headings: assessment and achievement, understanding of reading development, and teaching of reading. Although data were limited in scope, patterned responses around the concept of levels were intriguing and noteworthy.

Participants in this study (n=5) were required to take the literacy methods course at the onset of their teacher education program. This course was a requirement for all students in the teacher education program, not only those interested in pursuing elementary (Kindergarten to Grade 3) or middle years (Grade 4 to Grade 8) teaching careers. The survey included questions that asked respondents to consider aspects of reading development and pedagogy that would apply specifically to beginning readers and other questions addressed aspects of reading applicable to any grade level.

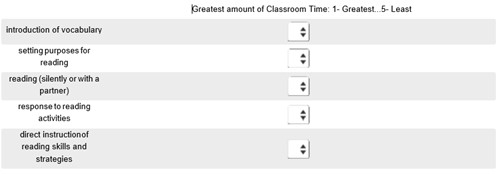

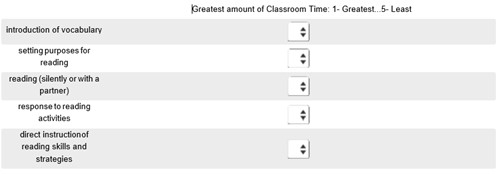

Respondents were asked to identify their preferred grade level. Based on these responses, three participants identified a preferred interest in elementary teaching (Kindergarten-Grade 3), and two identified a preferred interest in teaching middle years (Grades 4-8). Most questions on the survey were broad in scope; however, four questions asked respondents to consider their preferred grade level when answering. Additionally, one question asked respondents to consider their response through the lens of a Grade 1 teacher and another through the lens of a Grade 8 teacher. Specific questions related to reading development and instruction include but are not limited to:

· What would you consider to be key factors that support the reading development of students?

· How will you know if your students are reaching their full potential as readers?

· What kinds of things do you think are important for teachers to teach directly, in support of children’s reading progress?

· When teaching beginning readers, what type of text would you want to use to support reading development? Why?

o “A fat rat sat. The cat ran at the rat. Sad rat.”

o “I like to run. I like to skip. I like to jump. I love to play.”

An emergent theme, based on the coding process, reflected the popularity and use in classrooms of various levelling systems (Fountas & Pinnell, 2006) for the assessment of and instruction in reading. Characterized through a balanced literacy approach, levelled texts are often used for instruction during guided reading, shared reading, and independent reading opportunities (Glasswell & Ford, 2010). Noted in the surveys was the broad scope of the understood use of levelled texts and levelling systems, not only as instructional and assessment tools but also as a way to depict reading development and reading proficiency. While the scope of the study sought to investigate early beliefs pertaining to reading development and instruction, aspects related to assessment are included in the findings as the theme of levelling inextricably linked the use of a levelled reading assessment system to recognize reading development and to guide instructional decisions.

Participants who identified a desire to teach elementary grade levels (n=3) appeared to believe that children's reading development is primarily assessed through a levelling system. In response to a question about how one would assess reading development, “Candace,” a parent and educational assistant, noted that they would use “standardized reading assessments such as F&P” along with reading in small groups. Specific reference to Fountas and Pinnell (F&P) suggests prior experiences with this assessment system, characterized by a progression through texts that are levelled as a representation of increasing difficulty. Additional responses suggested that reading development might be measured by achieving benchmarks when students demonstrate the use of the three cueing systems (i.e., relying on syntax, semantics, and graphic cues for reading) )Clay, 1993) and the students' ability to respond to comprehension questions based on levelled texts. When asked about key components to look for when assessing reading development, “Candace” listed “looking at the pictures for clues” and “contextual clues” as indicators. In response to a question asking what Grade 1 teachers should do regularly, “Marie,” a participant with experience as an educational assistant, emphasized using levelled assessments to identify the reading levels of students "regularly throughout the year."

The two participants interested in teaching middle years (n=2) seemed to consider the assessment of reading development in terms of a demonstrated proficiency in reading-related skills and strategies (e.g., reading fluently, ability to decode, knowledge of vocabulary, summarizing text). However, “Pam,” who indicated that she has a child who had difficulty learning to read, added that the assessment of reading development should consider the student’s ability to use “level-appropriate vocabulary” and “level-appropriate comprehension.”

Questions on the survey asked participants to consider key factors that support students’ reading development. Findings demonstrated that several of the participants referenced levelled texts in some capacity. “Marie” addressed the need for students to develop comprehension skills by reading texts “not below or above” but at the appropriate level. Similarly, “Rae,” a tutor for a student with a learning disability, indicated that a key factor in developing reading is for students to engage in interesting texts that are “reading level appropriate.”

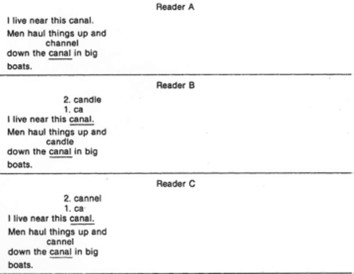

This study identified the use of the three cueing system as an indicator of children's reading development. When asked to identify the more proficient reader based on miscues, several respondents chose the reader who substituted a word with a word of similar meaning (reflective of the three cueing approach), one respondent chose the reader who attempted, unsuccessfully, to read the word phonetically, and one respondent justified both types of readers as being the more proficient reader, as one is attempting to decode the written word and the other considers that replacing the word with a synonym retains the meaning of the text.

When considering aspects of reading instruction, survey responses appeared to cover a spectrum ranging from dispositional characteristics (e.g., exemplary reading teachers are patient, ignite passion, empower students, and support success) to emphasis on the direct teaching of skills and strategies. However, the data showed the use of levelling systems for instructional purposes. One participant referenced that directing instruction to the identified level is critical to supporting reading acquisition. “Marie” noted that part of their home reading program would be:

for students to take books from their reading level home to read with their parents. This allows the parents to see where I have assessed their reading level to be and for them to engage with them in a level-appropriate manner around reading development.

Relatedly, participants were asked to identify which type of text they would use to support the reading development of beginning readers. One example reflected decodable text, focusing on regular letter-sound patterns (Bogan, 2012). Words in this text were tightly controlled—including one vowel sound, seven consonants, and one high-frequency word (“the”). The other example reflected a pattern or predictable text. The phrase "I like to" was repeated three times and changed to "I love to" in the last sentence. The last word of each sentence exhibited an action (e.g., run, skip, jump, play) that could be demonstrated in the illustration. A characteristic of many early-level texts for beginning readers is the repetition of words or phrases, often referred to as pattern (or predictable) texts. In these books, illustrations serve to enhance the relationship between pictures and written words, offering support to predict the text (Bogan, 2012). Predictable texts encourage beginning readers to draw on semantic, syntactic, and visual cues (three cueing system) for word reading. When asked to consider the type of text they would use with beginning readers to support reading development, several respondents chose the text that would be considered predictable, or patterned, emphasizing the use of the pictures and context to support word reading. Participants who chose the decodable text reasoned that this type of text focused attention on the letter-sound correspondences.

Preservice teachers who participated in this study emphasized levelling systems that permeated through their understandings of reading development and pedagogical approaches. However, identifying children's reading development through the lens of a levelling gradient limits understanding of the complex nature of reading and the depth of knowledge required to support children as they learn to read, especially the high number of those who find learning to read difficult. Results of this study highlight the importance of surfacing the beliefs and prior understandings (or misunderstandings) that PSTs bring with them early in their teacher education programs—primarily the reductive narrative framing of children as ‘levels’—and the benefit that required methods courses have as an avenue to address misconceptions.

When teacher educators are aware of the understandings PSTs hold, courses can be shaped to address and provoke shifts in understanding. Hikida et al. (2019) suggest:

The activities undertaken in classrooms during “reading time” are what students come to believe reading to be. We argue that teacher educators and researchers could benefit from being (re) reminded of this axiom. That is, what preservice teachers do during their literacy preparation is what they believe the teaching of reading to be. (p. 191)

Literacy courses offer the opportunity to revise preservice teachers' beliefs with content and pedagogical approaches that align with an interdisciplinary evidence base.

The prominence of associating levels with reading development requires attention. Responses to the survey by some PSTs suggested that they would know children are developing their reading skills if they achieved identified benchmarks throughout the year. When reading development is correlated to advancing through a levelled gradient, studies have shown that children define themselves as readers in terms of a level and ascertain who amongst their peers is a strong reader and who is a weak reader based on those levels (Forbes, 2008; Pierce, 1999). Identifying one's reading development along a levelled gradient may have a negative influence (Forbes, 2008) and has the potential to hinder factors for learning to read, such as motivation, interest, and self-efficacy, all of which Tunmer and Hoover (2019) suggested may indirectly impact reading acquisition.

Levelling systems assign a rank, or level, based on characteristics of the text, which are highly subjective (Moats, 2017). In fact, in an analysis of sample texts from one series of levelled books published in the United States, Picher and Fang (2007) found that the levelling system was not a reliable indicator of text difficulty, and the quality varied substantially between and within levels. The authors cautioned that reliance on text levels could be unfavourable in the reader–text matching process. Research has cast doubt on the notion of “instructional levels” (Jorgenson et al., 1977; Kuhn et al., 2006; Morgan et al., 2000; O'Connor et al., 2010; Stahl & Heubach, 2005); however, this term is widely used in education (Burns et al., 2015). PSTs in this study placed importance on matching text to the readers. “Marie” noted that "reading things that are their reading level" was critical in supporting reading development. “Elizabeth Marie” suggested that exemplary reading teachers "teach to the level that each student requires" and identified her strength as a reading teacher, ensuring each child is at the correct level. As well, “Marie” indicated that levelled texts would be used as part of a home reading program, providing opportunities for the child to practice these texts at home and "for the parents to see where I have assessed their reading level to be." Attention here appeared to focus on assessing the progression and identification of levels instead of assessing and identifying reading-related skills.

Participants in this study did not refer to reading development in terms of the acquisition and development of processes and skills required to move from learning the alphabetic principle to applying that knowledge to written words. Ehri (1995) considers word reading development through a series of qualitatively distinct phases, described as pre-alphabetic, partial alphabetic, full alphabetic, and consolidated alphabetic. Central to the characteristics of each phase are the reader's knowledge of the alphabetic system and mastery of the sound/spelling correspondences in words. Knowledge and understanding of the qualitative characteristics of reading development provide a basis for monitoring progress and differentiating instruction. As PSTs in the current study presented their understandings of reading development and instruction in relation to a levelled gradient and matching texts to readers, it would be necessary for teacher educators to unpack those beliefs and facilitate opportunities to build understandings of reading acquisition and the most effective instruction that is supported by evidence.

Using levelled texts to teach early reading is prevalent in classrooms (Cunningham et al., 2005; Moats, 2017). Early levels often appear as predictable texts characterized by semantically predictable and repeated language patterns and with illustrations that match the print. These sources support the use of the three cueing systems for word recognition. As texts increase along the levelled gradient, predictability declines; however, the instructional emphasis of the earlier texts is to foster the coordinated use of the three cueing systems, which is then applied to texts of increased difficulty. The three cueing model, which focuses on the semantic system, is a foundational component of balanced literacy instruction (Kilpatrick, 2015). Reference to utilizing the three cueing systems model permeated the surveys in responses around supporting word reading and identifying proficient readers, which is reflective of a balanced literacy influence.

Kilpatrick (2015) further suggested that the three cueing model is problematic as it pertains to word reading and suggests that weak readers, not skilled readers, rely heavily on context for word reading. Rather than the semantic system, the connection between the orthographic and phonological systems supports skilled word reading. Reading materials that promote the application of students' knowledge of sound/symbol relationships facilitate storing familiar letter sequences for later recognition and retrieval. These texts, referred to as decodables, accelerate mastery of phonics skills and increase activity in those areas of the brain wired for skilled reading (Kilpatrick, 2015). However, findings in this study reflect PSTs' privileging of levelled, or predictable texts, over decodable texts for beginning readers and reasoned that the repeated words and phrases supported reading development.

PSTs in this study initially appeared to have a narrow understanding of how reading materials can be used to support reading development. “Rae” suggested that decodable texts allow students to "fully comprehend the sound that the letters make" and “Pam” stated that "it's good to start with soft vowels and similar sounds." PSTs who identified they would use predictable texts for beginning readers justified their choice, sighting that the text's meaning, pattern, and predictability, along with picture cues, best supported reading development. Participant responses demonstrated limited knowledge of how decodable texts should be used to support reading development in the transitory phase as students are learning and applying the code in connected text and that once students reach the consolidated phase, their print lexicons and knowledge of letter patterns enable them to read a variety of text types, including levelled texts. While a deep understanding of reading acquisition is not expected or required at the beginning of a PST’s first literacy methods course, this data suggests that many PSTs do come with deeply entrenched beliefs on reading that must be articulated and, subsequently, engaged within the teacher education instruction that follows.

Data from this study in surfacing the beliefs and understandings of PSTs demonstrated a limited, narrow view of various aspects of reading development and instruction. This is problematic when these beliefs and understandings do not reflect current evidence on reading acquisition and instruction. Methods courses offer the opportunity to examine pre-existing beliefs and begin to develop knowledge of the foundational processes required for skilled reading (Stainthorp, 2004). In response to criticism indicating that teacher education programs do not adequately prepare teacher candidates for early reading instruction (Bos et al., 2001; Carlisle et al., 2009; Cheesman et al., 2010; Joshi et al., 2009; Mathes & Torgesen, 1998; Moats, 1994, 2014; Piasta et al., 2009), instructors in literacy methods courses can create space to surface prior understandings held by PSTs and shape course content to address misconceptions and gaps in understandings.

Surfacing the beliefs and understandings that PSTs bring to literacy methods courses can shape the content and experiences of these courses, providing one avenue for PSTs to examine and refine their understandings related to reading instruction and development. Findings from Massey (2010) support the benefit of deep, concentrated instruction and the necessity to surface prior knowledge and beliefs to provide opportunities to add to or change existing knowledge. Duffy and Atkinson (2001) and Brenna and Dunk (2018) also noted the importance of providing preservice teachers with opportunities to address misunderstandings about reading and reading instruction.

Although based on a small participant pool, the results of this pilot study are significant as we consider how children are defined as readers by policy and pre-/in-service teachers alike. Current practices, guided by provincial curricula, rely heavily on the use of levelled reading assessments and instructional/independent level texts for instruction, perpetuating the identification of children as levels. Teachers emphasize the levelled gradient and the defined benchmarks reflecting reading development throughout each grade. Implications of the prevalence of a levelled gradient are apparent in the reliance on this gradient to measure growth and proficiency, make instructional decisions, and limit text choice. Notable is that PSTs who participated in this study brought these beliefs and understandings around the use of levelling systems to their initial literacy methods course, begging the question: Where are these beliefs stemming from? Literacy methods courses have the capacity to offer PSTs a deep knowledge of the phases of reading acquisition, characteristics within these phases, and pedagogical expertise to support development through these phases, providing a more robust understanding of how children develop as readers. A narrow, limited view of reading development through the lens of a levelled gradient is not the only implication of an over-reliance on these systems. Children also identify themselves as readers with reference to a level, comparing themselves to their peers—both of which have the potential to be detrimental to their confidence and belief about their identity as readers.

Learning to read is a complex process that requires teachers to have a depth of knowledge of content—the skills and strategies required for proficient reading, and of pedagogy—and the instructional approaches that best facilitate the acquisition of those skills and strategies. This depth of knowledge also allows teachers to be flexible in their approaches to adjust instruction to support struggling students skillfully. This is not a trivial undertaking. It is recommended that post-secondary institutions recognize the intricacy that is learning to read and that literacy methods courses are not only required but that the sequence of these courses is designed to facilitate learning experiences for PSTs to unpack and negotiate prior beliefs while engaging in learning opportunities to develop knowledge and application of instruction reflective of current research. "Candace" made a striking statement in a survey response: "I wish that there was a university course that provided more direction in teaching reading." Perhaps it is necessary to evaluate currently required literacy methods courses to ensure they are designed in a way that develops and builds critical knowledge of content and instruction. This study offers findings that have the potential to influence aspects of teacher education programs, including the value of surfacing beliefs and understandings and adjusting course content to address possible misconceptions about reading development and reading pedagogy.

Although the results of this study are limited in scope, the findings offer avenues for further consideration. The emphasis placed on levelling systems to define reading development and focus instructional decisions is fascinating. Future studies could unpack these beliefs and how these understandings are negotiated after completing literacy methods courses. Additionally, it is worthy of further inquiry to examine the understandings PSTs bring with them from their experiences in learning to read and how that may influence their pedagogical decisions.

The qualitative approach to this inquiry recognizes that interpretations of the data were constructed through the insights and perspectives that I, as the researcher, carried forward to the study. It is possible that the use of the term “levels” (or variations of this term) by the participants could have held an intention different than that interpreted by the researcher. References to the notion of "levels" surfaced over various questions (e.g., in a question relating to assessment or a question relating to a type of instructional text), and all of the participants in the study referred to "levels" at some point in their responses.

As is the nature of qualitative research, this study's findings reflect the participants' shared understandings at a moment in time. These findings are not meant to reflect the PSTs enrolled in the literacy methods course who did not participate in the study nor generalized beyond the scope of this study.

The number of participants in this study reflected a small sample size. This research was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, and it was the first semester that instructors and students were forced to learn online. Site recruitment posed a challenge as many instructors were shifting courses to online platforms and felt they were not in a place to offer engagement in a study to their students. The limited participation in this study may reflect the additional factors impacting student learning and engagement during this time. Despite these limitations, examining PSTs’ initial beliefs remains a generative avenue of exploration as teacher educators consider how to best prepare PSTs through meaningful teacher education courses that are responsive to PSTs' needs, and, ultimately, the needs of the students they will teach. Initial course surveys, such as the one this article discusses, are a meaningful avenue through which researchers and educators can engage in this exploration toward PST learning and unlearning.

Adams, M. J. (1991). Beginning to read: Thinking and learning about print. MIT Press.

Adams, P. (2006). Exploring social constructivism: Theories and practicalities. Education 3-13, 34(3), 243-257. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004270600898893

Andrew, K., Richards, R., Graber, K. C., & Woods, A. M. (2018). Using theory to guide research: Applications of constructivist and social justice theories. Kinesiology Review, 7, 218-225. https://doi.org/10.1123/kr.2018-0018

Angelou, M. (2012). The collected autobiographies of Maya Angelou. Random House Publishing.

Azzarito, L., & Ennis, C. D. (2003). A sense of connection: Toward social constructivist physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 8(2), 179-198. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573320309255

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall.

Bogan, B. L. (2012). Decodable and predictable texts: Forgotten resources to teach the beginning reader. International Journal of Arts and Commerce, 1(6), 1-8.

Bos, C., Mather, N., Dickson, S., Podhajski, B., & Chard, D. (2001). Perceptions and knowledge of preservice and inservice educators about early reading instruction. Annals of Dyslexia, 51, 97-120. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11881-001-0007-0

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brenna, B. & Dunk, A. (2018). Preservice teachers explore their development as teachers of reading. In E. Lyle (Ed.), The negotiated self: Employing reflexive inquiry to explore teacher identity (197-212). Brill Sense. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004388901_017

Brenna, B. & Dunk, A. (2019). Preservice teachers defining and redefining reading and the teaching of reading. Language and Literacy, 21(4), 21-40. https://doi.org/10.20360/langandlit29442

Building Student Success - B.C. curriculum. (n.d.). https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/curriculum/english-language-arts/1/core

Brodeur, K., & Ortmann, L. (2018). Preservice teachers’ beliefs about struggling readers and themselves. Mid-Western Educational Researcher, 30(1-2), 1-27. https://www.mwera.org/MWER/volumes/v30/issue1_2/V30n1_2-Brodeur-FEATURE-ARTICLE.pdf

Bryan, L. A. (2003). Nestedness of beliefs: Examining a prospective elementary teacher’s belief system about science teaching and learning. Journal of Research in Science Training, 40(9), 835–868. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.10113

Buckingham, J., Beaman, R., & Wheldall, K. (2013). Why poor children are more likely to become poor readers: The school years. Australian Journal of Education, 57(3), 187-311. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004944113495500

Burns, M. K., Pulles, S. M., Maki, K. E., Kanive, R., Hodgson, J., Helman, L. A., McComas, J. J., & Preast, J. L. (2015). Accuracy of student performance while reading leveled books rated at their instructional level by a reading inventory. Journal of School Psychology, 53, 437-445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2015.09.003

Canadian Language and Literacy Research Network (CLLRN). (2009). National strategy for early literacy: Report and recommendations. http://en.copian.ca/library/research/nsel/report/report.pdf

Carlisle, J., Correnti, R., Phelps, G., & Zeng, J. (2009). Exploration of the contribution of teachers’ knowledge about reading to their students’ improvement in reading. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 22(4), 457-486. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-009-9165-y

Castles, A., Rastle, K., & Nation, K. (2018). Ending the reading wars: Reading acquisition from novice to expert. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 19, 5-51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100618772271

Chall, J. (1967). Learning to read: The great debate. McGraw-Hill.

Chall J. S. (1983). Learning to read: The great debate (updated edition). McGraw-Hill.

Cheesman, E. A., Hougen, M., & Smartt, S. M. (2010). Higher education collaboratives: Aligning research and practice in teacher education. Perspectives on Language and Literacy, 36(4), 31-35. https://meadowscenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/highereducationcollaboratives20101.pdf

Ciampa, K., & Gallagher, T. L. (2018). A comparative examination of Canadian and American preservice teachers' self-efficacy beliefs for literacy instruction. Reading and Writing, 31(2), 457-481. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11145-017-9793-6

Clay, M. M. (1993). Reading recovery: A guidebook for teachers in training. Heinemann.

Clift, R. T., & Brady, P. (2009). Research on methods courses and field experiences. In M. Cochran-Smith & K. M. Zeichner (Eds.), Studying teacher education: The report of the AERA panel on research and teacher education (pp. 309-424). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cohen, R. A., Mather, N., Schneider, D. A., & White, J. M. (2016). A comparison of schools: Teacher knowledge of explicit code-based reading instruction. Reading and Writing, 30, 653-690. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-016-9694-0

Cunningham, A. E., Perry, K. E., Stanovich, K. E., & Stanovich, P. J. (2004). Disciplinary knowledge of K-3 teachers and their knowledge calibration in the domain of early literacy. Annals of Dyslexia, 54(1), 139-167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11881-004-0007-y

Cunningham, J. W., Spadorcia, S. A., Erickson, K. A., Koppenhaver, D. A., Sturm, J. M., & Yoder, D. E. (2005). Investigating the instructional supportiveness of leveled texts. Reading Research Quarterly, 40(4), 410-427. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.40.4.2

Darling-Hammond, L. (1996). What matters most: A competent teacher for every child. Phi Delta Kappan, 78(3), 193-200.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2000). Teacher quality and student achievement: A review of state policy evidence. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 8(1), 1-44. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v8n1.2000

Debreli, E. (2016). Preservice teachers' belief sources about learning and teaching: An exploration with the consideration of the educational programme nature. Higher Education Studies, 6(1), 116-127. https://doi.org/10.5539/hes.v6n1p116

Derby, M., & Ranginui, N. (2018). ‘H’ is for human right: An exploration of literacy as a key contributor to indigenous self-determination. Kairaranga, 19(2), 39-46. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1240207.pdf

Draper, R. J. (2008). Redefining content-area literacy teacher education: Finding my voice through collaboration. Harvard Educational Review, 78(1), 60-83. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.78.1.k104608143l205r2

Duffy, A. M., & Atkinson, T. S. (2001). Learning to teach struggling (and non-struggling) elementary school readers: An analysis of preservice teachers’ knowledges. Reading Research and Instruction, 41, 83-102. https://doi.org/10.1080/19388070109558359

Dunk, A. (2021). Identifying as a teacher of reading: A case study of pre-service teachers’ beliefs about reading and the teaching of reading over the duration of a required ELA course. [Doctoral dissertation, University of Saskatchewan]. Harvest. https://hdl.handle.net/10388/13734

Ehri, L. C. (1995). Phases of development in learning to read words by sight. Journal of Research in Reading, 18(2), 116-125. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1111/j.1467-9817.1995.tb00077.x

Erlingsson, C., & Brysiewicz, P. (2013). Orientation among multiple truths: An introduction to qualitative research. African Journal of Emergency Medicine, 3(2), 92-99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.afjem.2012.04.005

Fang, Z. (2012). The challenges of reading disciplinary texts. In T. L. Jetton & C. Shanahan (Eds.), Adolescent literacy in the academic disciplines: General principles and practical strategies (pp. 34-68). The Guildford Press.

Fien, H., Chard, D. J., & Baker, S. K. (2021). Can the evidence revolution and multi-tiered systems of support improve education equity and reading achievement? Reading Research Quarterly, 56(S1), S105-S118. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.391

Forbes, D. C. (2008). “I wanted to lie about my level” A self study: How my daughter’s experiences with leveled books became a lens for re-imaging myself as a literacy educator [Master’s thesis, University of Manitoba]. ProQuest. https://mspace.lib.umanitoba.ca/server/api/core/bitstreams/16802866-643d-4ef8-8440-891beb0bc071/content

Fountas, I. C., & Pinnell, G. S. (2006). Leveled books K-8: Matching texts to readers for effective teaching. Heinemann.

Gay, G. (2013). Teaching to and through cultural diversity. Curriculum Inquiry, 43(1), 48-70. https://doi.org/10.1111/curi.12002

Glasswell, K., & Ford, M. P. (2010). Teaching flexibly with leveled texts: More power for your reading block. The Reading Teacher, 64(1), 57-60. https://doi.org/10.1598/RT.64.1.7

Goodman, K. S. (1967). Reading: A psycholinguistic guessing game. Journal of the Reading Specialist, 6(4), 126–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/19388076709556976

Gough, P. B., Alford, J. A. Jnr., & Holley-Wilcox, P. (1981). Words and contexts. In O. J. L. Tzeng & H. Singer (Eds.), Perception of print: Reading research in experimental psychology (pp. 85-102). Erlbaum Associates.

Gove, M. K. (1983). Clarifying teachers’ beliefs about reading. The Reading Teacher, 37(3), 261-268. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20198450

Government of Saskatchewan. (2014). Education sector strategic plan, 2014-2020. https://www.saskatchewan.ca/-/media/news-release-backgrounders/2014/april/education-strategic-sector-plan-2014.pdf

Gregoire, M. (2003). Is it a challenge or a threat? A dual-process model of teachers’ cognition and appraisal processes during conceptual change. Educational Psychology Review, 15(2), 147-179. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023477131081

Guerriero, S. (Ed.) (2017). Pedagogical knowledge and the changing nature of the teaching profession. OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264270695-en

Hammond, Z. (2020). Distinctions of equity. Crtandthebrain. https://crtandthebrain.com/wp-content/uploads/Hammond_Full-Distinctions-of-Equity-Chart.pdf

Hempenstall, K. (2006). The three-cueing model: Down for the count? EdNews.org https://www.thereadingleague.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/3-Cueing-Systems-Hempenstall-2006.pdf

Hempenstall, K. (2016). Read about it: Scientific evidence for effective teaching of reading. CIS Research Report 11. Sydney: The Centre for Independent Studies. https://dataworks-ed.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Kerry.pdf

Hikida, M., Chamberlain, K., Tily, S., Daly-Lesch, A., Warner, J. R., & Schallert, D. L. (2019). Reviewing how preservice teachers are prepared to teach reading processes: What the literature suggests and overlooks. Journal of Literacy Research, 50(2), 177-195. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086296X19833297

International Literacy Association. (2018). Standards for the preparation of literacy professionals 2017. https://literacyworldwide.org/get-resources/standards/standards-2017

Jorgenson, G. W., Klein, N., & Kumar, V. K. (1977). Achievement and behavioral correlates of matched levels of student ability and materials difficulty. Journal of Educational Research, 71(2), 100-103. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.1977.10885045

Joshi, R. M., Binks, E., Hougen, M., Dahlgren, M. E., Ocker-Dean, E., & Smith, D. L. (2009). Why elementary teachers might be inadequately prepared to teach reading. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 42(5), 392-402. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219409338736

Kagan, D. M. (1992). Professional growth among preservice and beginning teachers. Review of Educational Research, 62(2), 129-169. https://doi.org/10.3102%2F00346543062002129

Kilpatrick, D. A. (2015). Essentials of assessing, preventing, and overcoming reading difficulties. Wiley.

Kuhn, M. R., Schwanenflugel, P. J., Morris, R. D., Morrow, L. M., Woo, D. G., Meisinger, E. B., Sevcik, R, A., Bradley, B. A., & Stahl, S. A. (2006). Teaching children to become fluent and automatic readers. Journal of Literacy Research, 38(4), 357-387. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15548430jlr3804_1

Leko, M., & Mundy, C. A. (2011). Understanding preservice teachers’ beliefs and their constructions of knowledge for teaching reading to struggling readers. Kentucky Teacher Education Journal: The Journal of the Teacher Education Division of the Kentucky Council for Exceptional Children, 1(1), 1-19. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/ktej/vol1/iss1/1

Lesaux, N. K., & Siegel, L. S. (2003). The development of reading in children who speak English as a second language. Developmental Psychology, 39(6), 1005-1019. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.39.6.1005

Lincoln, Y. S., Lynham, S. A., & Guba, E. G. (2018). Paradigmatic controversies: Contradictions, and emerging confluences, revisited. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (5th ed., pp. 108-150). SAGE.

Liu, K., Robinson, Q., & Braun-Monegan, J. (2016). Pre-service teachers identify connections between teaching-learning and literacy strategies. Journal of Education and Training Studies, 4(8), 93-98. http://dx.doi.org/10.11114/jets.v4i8.1538

Lyon, G. R. (1998). Why reading is not a natural process. Educational Leadership, 55(6), 14-18. https://www.buddies.org/articles/extlyon.pdf

Lyon, G. R. (2003, September 11). An interview…Dr. G. Reid Lyon- Converging evidence- Reading research what it takes to read [Interview]. Children of the Code. https://childrenofthecode.org/interviews/lyon.htm

Lyon, G. R., & Weiser, B. (2009). Teacher knowledge, instructional expertise, and the development of reading proficiency. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 42(5), 475-480. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0022219409338741

Maloch, B., Seely Flint, A., Eldridge, D., Harmon, J., Loven, R., Fine, J. C., Bryant-Shanklin, M., & Martinez, M. (2003). Understandings, beliefs, and reported decision making of first-year teachers from different reading teacher preparation programs. The Elementary School Journal, 103(5), 431-457. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1002112

Manitoba Ministry of Education (2019). English language arts curriculum framework: A living document. https://www.edu.gov.mb.ca/k12/cur/ela/framework/index.html

Massey, D. D. (2010). Personal journeys: Teaching teachers to teach literacy. Literacy Research and Instruction, 41(2), 103-125. https://doi.org/10.1080/19388070209558361

Mathes, P. G., & Torgesen, J. K. (1998). All children can learn to read: Critical care for the prevention of reading failure. Peabody Journal of Education, 73(3/4), 317-340. https://doi.org/10.1080/0161956X.1998.9681897

McCutchen, D., Harry, D. R., Cunningham, A. E., Cox, S., Sidman, S., & Covill, A. E. (2002). Reading teachers’ knowledge of children’s literature and English phonology. Annals of Dyslexia, 52, 207-228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11881-002-0013-x

Meeks, L. J., & Kemp, C. R. (2017). How well prepared are Australian preservice teachers to teach early reading skills? Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 42(11), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2017v42n11.1

Meeks, L., Stephenson, J., Kemp, C., & Madelaine, A. (2016). How well prepared are pre-service teachers to teach early reading? A systematic review of the literature. Australian Journal of Learning Difficulties, 21(2), 69-98. https://doi.org/10.1080/19404158.2017.1287103

Merriam, S. B. (1988). Case study research in education: A qualitative approach. Jossey-Bass Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001416-199101000-00021

Merriam, S. B. (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. Jossey-Bass.

Ministry of Education. (n.d.). Framework for a provincial education plan 2020-2030. https://publications.saskatchewan.ca/#/products/103407

Moats, L. C. (1994). The missing foundation in teacher education: Knowledge of the structure of spoken and written language. Annals of Dyslexia, 44, 81-102. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02648156

Moats, L. (2009). Still wanted: Teachers with knowledge of language. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 42(5), 387-391. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219409338735

Moats, L. (2014). What teachers don’t know and why they aren’t learning it: Addressing the need for content and pedagogy in teacher education. Australian Journal of Learning Difficulties, 19(2), 75–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/19404158.2014.941093

Moats, L. (2017). Can prevailing approaches to reading instruction accomplish the goals of RTI? Perspectives on Language and Literacy, 43(3), 15-22. https://dyslexialibrary.org/wp-content/uploads/file-manager/public/1/Summer%202017%20Final%20Moats%20p15-22.pdf

Moats, L. C. (2020). Teaching reading is rocket science, 2020: What expert teachers of reading should know and be able to do. American Federation of Teachers. https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/moats.pdf

Moats, L. C., & Foorman, B. R. (2003). Measuring teachers’ content knowledge of language and reading. Annals of Dyslexia, 53, 23-45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11881-003-0003-7

Moore, H. (2020). Investigating preservice teachers’ instructional decision-making for reading [Doctoral dissertation, University of North Carolina at Greensboro]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. https://www.proquest.com/openview/80b8c05003e648ff1d7ee97563d49310/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=51922&diss=y

Morgan, A., Wilcox, B. R., & Eldredge, J. L. (2000). Effect of difficulty levels on second-grade delayed readers using dyad reading. Journal of Educational Research, 94(2), 113-119. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220670009598749

Muñoz, M. A., Prather, J. R., & Stronge, J. H. (2011). Exploring teacher effectiveness using hierarchical linear models: Student- and classroom- level predictors and cross- year stability in elementary school reading. Planning and Changing, 42(3/4), 241-273. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ975995.pdf

National Council on Teacher Quality. (2023). Teacher prep review: Strengthening elementary reading instruction. https://www.nctq.org/dmsView/Teacher_Prep_Review_Strengthening_Elementary_Reading_Instruction

National Reading Panel (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel: Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction: Reports of the subgroups. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/sites/default/files/publications/pubs/nrp/Documents/report.pdf

Neuman, S. B., Quintero, E., & Reist, K. (2023, July). Reading reform across America: A survey of state legislation. Albert Shanker Institute. https://www.shankerinstitute.org/sites/default/files/2023-07/ReadingReform%20ShankerInstitute%20FullReport%20072723.pdf

Nierstheimer, S. L., Hopkins, C. J., Dillon, D. R., & Schmitt, M. C. (2000). Preservice teachers’ shifting beliefs about struggling literacy learners. Literacy Research and Instruction, 40(1), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/19388070009558331

O’Connor, R. E., Swanson, L. H., & Geraghty, C. (2010). Improvement in reading rate under independent and difficult text levels: Influences on word and comprehension skills. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(1), 1-19. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/a0017488

Olson, M. R. (1995). Conceptualizing narrative authority: Implications for teacher education. Teaching & Teacher Education, 11(2), 119-135. https://doi.org/10.1016/0742-051X(94)00022-X

Ontario Human Rights Commission. (2022). Right to read: Public inquiry into human rights issues affecting students with reading disabilities. Ontario Human Rights Commission. https://www.ohrc.on.ca/sites/default/files/FINAL%20R2R%20REPORT%20DESIGNED%20April%2012.pdf

Otaiba, S. A., Lake, V. E., Scarborough, K., Allor, J., & Carreker, S. (2016). Preparing beginning reading teachers for K-3: Teacher preparation in higher education. Perspectives on Language and Literacy, 42(4), 25-32. http://www.onlinedigeditions.com/publication/?m=13959&i=346259&p=2&ver=html5

Otaiba, S. A., & Torgesen, J. (2007). Effects from intensive standardized kindergarten and first-grade interventions for the prevention of reading difficulties. In S. R. Jimerson, M. K. Burns, & A. M. VanDerHeyden (Eds.), Handbook of Response to Intervention (pp. 212-222). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-49053-3_15

Parker, D. C., Zaslofsky, A. F., Burns, M. K., Kanive, R., Hodgson, J., Scholin, S. E., & Klingbeil, D. A. (2015). A brief report of the diagnostic accuracy of oral reading fluency and reading inventory levels for reading failure risk among second- and third- grade students. Reading and Writing Quarterly, 31(1), 56-67. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573569.2013.857970

Piasta, S. B., McDonald Connor, C., Fishman, B. J., & Morrison, F. J. (2009). Teachers’ knowledge of literacy concepts, classroom practices, and student reading growth. Scientific Studies of Reading, 13(3), 224-248. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888430902851364

Picher, B., & Fang, Z. (2007). Can we trust levelled texts? An examination of their reliability and quality from a linguistic perspective. Literacy, 41(1), 43-51. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9345.2007.00454.x

Pierce, K. M. (1999). “I am a level 3 reader: Children’s perceptions of themselves as readers. New Advocate, 12(4), 359–375.

Pratt, S. M., & Urbanowski, M. (2015). Teaching early readers to self-monitor and self-correct. The Reading Teacher, 69(5), 559-567. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1443

Pressley, M., Roehrig, A., Bogner, K., Raphael, L. M., & Dolezal, S. (2002). Balanced literacy instruction. Focus on Exceptional Children, 34(5), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.17161/foec.v34i5.6788

Richardson, V., Anders, P., Tidwell, D., & Lloyd, C. (1991). The relationship between teachers’ beliefs and practices in reading comprehension instruction. American Educational Research Journal, 28(3), 559-586. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312028003559

Risko, V. J., Roller, C. M., Cummins, C., Bean, R. M., Collins Block, C., Anders, P. L., & Flood, J. (2008). A critical analysis of research on reading teacher education. Reading Research Quarterly, 43(3), 252-288. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.43.3.3

Rivkin, S. G., Hanushek, E. A., & Kain, J. F. (2005). Teachers, schools, and academic achievement. Econometrica, 73(2), 417-458. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0262.2005.00584.x

Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission. (2023). Equitable education for students with reading disabilities in Saskatchewan’s K to 12 schools: A systemic investigation report. Systemic Initiatives. https://saskatchewanhumanrights.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SHRC-Reading-Disabilities-Report-Sept-2023.pdf

Saskatchewan Ministry of Education. (2010). Saskatchewan English Language Arts Curriculum. https://www.edonline.sk.ca/webapps/moe-curiculum-BBLEARN/CurriculumHome?id=27

Saskatchewan Ministry of Education. (2020). Annual report for 2019-2020. https://pubsaskdev.blob.core.windows.net/pubsask-prod/119955/2019-20EducationAnnualReport.pdf

Saskatchewan Ministry of Education (2021), Grades 1-3 reading data collection information booklet. Government of Saskatchewan. https://www.edonline.sk.ca/bbcswebdav/pid-84319-dt-content-rid-9687994_1/xid-9687994_1

Saskatchewan Ministry of Education (2024). Annual report 2023-24. https://publications.saskatchewan.ca/api/v1/products/124182/formats/144629/download

Savage, R., Georgiou, G., Parrila, R., & Maiorino, K. (2018). Preventative reading interventions teaching direct mapping of graphemes in texts and set-for-variability aid at-risk learners. Scientific Studies of Reading, 22(3), 225-247. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2018.1427753

Shanahan, T., & Shanahan, C. (2008). Teaching disciplinary literacy to adolescents: Rethinking content-area literacy. Harvard Educational Review, 78(1), 40-59. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.78.1.v62444321p602101

Skott, J. (2014). The promises, problems, and prospects of research on teacher beliefs. In H. Fives & M. G. Gill (Eds.), International handbook of research on teachers’ beliefs (pp. 13-30). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203108437-8

Smagorinsky, P., & Barnes, M. E. (2014). Revisiting and revising the apprenticeship of observation. Teacher Education Quarterly, 41(4), 29-52. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/teaceducquar.41.4.29

Snow, C. E., Burns, M. S., & Griffin, P. (1998). Preventing reading difficulties in young children. National Academy Press. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.10011

Snowling, M. J., Moll, K., & Hulme, C. (2021). Language difficulties are a shared risk factor for both reading disorder and mathematics disorder. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 202, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2020.105009

Stahl, S. A., & Heubach, K. M. (2005). Fluency-oriented reading instruction. Journal of Literacy Research, 37, 25-60. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15548430jlr3701_2

Stainthorp, R. (2004). W(h)ither phonological awareness? Literate trainee teachers’ lack of stable knowledge about the sound structure of words. Educational Psychology, 24(6), 753-765. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144341042000271728

Stark, H. L., Snow, P. C., Eadie, P. A., & Goldfeld, S. R. (2016). Language and reading instruction in early years’ classrooms: The knowledge ad self-rated ability of Australian teachers. Annals of Dyslexia, 66, 28-54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11881-015-0112-0

State Collaborative on Reforming Education. (2020). The science of reading. https://tnscore.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Science-of-Reading-2020.pdf

Tunmer, W. E., & Hoover, W. A. (1993). Phonological recoding skill and beginning reading. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 5, 161-179. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01027482

Tunmer, W. E., & Hoover, W. A. (2019). The cognitive foundations of learning to read: A framework for preventing and remediating reading difficulties. Australian Journal of Learning Difficulties, 24(1), 75-93. https://doi.org/10.1080/19404158.2019.1614081

UNESCO (2019). UNESCO strategy for youth and adult literacy (2020-2025). https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000371411?posInSet=2&queryId=fab6406f-989c-4049-b36b-a2fb1c00bda3

Vacca, J. L., Vacca, T. T., & Gove, M. K. (1991). Reading and learning to read (2nd ed.). HarperCollins.

Vieira, A. (2019). Becoming a teacher of reading: Preservice teachers develop their understanding of teaching reading [Doctoral dissertation, University of Victoria]. UVicSpace Electronic Theses and Dissertations. http://hdl.handle.net/1828/11195

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvjf9vz4.5

Wright, S. P., Horn, S. P., & Sanders, W. L. (1997). Teacher and classroom context effects on student achievement: Implications for teacher evaluation. Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education, 11, 57-67. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007999204543