Artëm Ingmar Benediktsson

Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences

Artëm Ingmar Benediktsson http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6435-7485

There are no competing interests to declare.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Artëm Ingmar Benediktsson at artem.benediktsson@inn.no

This paper explores teacher educators’ endeavours to enhance their students’ cultural competence in the context of Danish teacher education. It analyses how these endeavours resonate with the theoretical principles of critical multiculturalism and multicultural education. The study employed dyadic interviews as its primary method for data collection. The findings revealed that the educators felt constrained by the lack of awareness among politicians and policymakers of the significance of multicultural education, which made it difficult for them to develop in-depth knowledge and critical views on culture among students. The educators emphasized a need for a holistic approach that encompasses systemic changes and a shift in mindset toward critical multiculturalism in teacher education. This study calls for more institutional accountability to invest in preparing future teachers to work in multicultural classrooms.

Keywords: teacher education, critical multiculturalism, cultural diversity, dyadic interviews, Denmark.

In the contemporary era of globalization, cultural and linguistic diversity in educational settings has evolved into an undeniable reality, offering a multitude of opportunities and advantages. Nevertheless, previous international research indicates that educational professionals at different educational levels continue to grapple with the establishment of learning environments that embrace this diversity (Benediktsson, 2023b; Borrero et al., 2018; Dervin, 2023; Dixson, 2021; Obondo et al., 2016; Ragnarsdóttir et al., 2023). In the context of Danish compulsory education, cultural and linguistic diversity has likewise become an everyday reality. Yet, a body of research indicates that school personnel are inadequately equipped, both in theoretical and practical terms, to implement teaching and assessment methods that incorporate pupils’ diverse cultural and linguistic identities into their education (Frederiksen et al., 2022; Häggström et al., 2020; Steffensen & Kjeldsen, 2021).

The Danish educational system is distinguished by its focus on the concept of togetherness [Danish: fællesskab], underscoring the significance of cultivating a sense of community and common spirit (Jantzen, 2020; Mason, 2020; Nielsen & Ma, 2021). In this context, togetherness is not just about being physically together; it also involves a shared feeling of belonging and collective purpose. Furthermore, the concept of togetherness stems from the philosophical tenets advocating that individual enlightenment and a fortified sense of belonging attained through education are essential for societal well-being (Jantzen, 2020; Mason, 2020). Nonetheless, within contemporary multicultural settings, school personnel need to examine this concept critically, particularly its merits and constraints. Such reflective practice may enable the effective adaptation of the concept of togetherness to foster learning environments characterized by cultural and linguistic diversity. In the absence of a comprehensive understanding of the concept of togetherness within contemporary contexts, educational institutions may fail to equip young people with a robust sense of empathy, social justice, and a critical view of policies and practices designed to advance equity (Nielsen & Ma, 2021).

The critical responsibility of higher education institutions offering teacher education programs is to provide future teachers with both theoretical knowledge and practical skills for empowering all children, regardless of their cultural, linguistic, socio-economic, or any other status. However, existing research within teacher education in Denmark and other Nordic countries has identified certain challenges in cultivating holistic perspectives on diversity and adequately preparing future teachers for work in multicultural classrooms. For instance, Ozuna (2022) conducted a comparative study of teacher education programs in California and Denmark, concluding that while Danish student teachers exhibited some understanding of methodologies appropriate for multicultural settings, they witnessed limited application of these methods during their practical training. Another comparative study involving Danish and Icelandic student teachers highlighted gaps in their understanding of assessment methods that account for cultural diversity (Benediktsson, 2023a). Both groups expressed the need for greater support and specialized training to implement these assessment methods effectively (Benediktsson, 2023a). Similarly, a Norwegian study within a five-year integrated teacher education program emphasized the need for improved preparation, specifically in teaching methods pertinent to cultural diversity, along with stronger connections between theoretical instruction and practical experience (Tavares, 2023).

This paper examines the perspectives of Danish teacher educators, specifically focusing on how they perceive and engage with cultural perspectives within teacher education programs. It explores their reflections on recognizing and incorporating the existing cultural diversity of contemporary Danish society into the education of future teachers. Utilizing data from three dyadic interviews with six teacher educators, the study seeks to address three central research questions:

What place do cultural perspectives hold in teacher education, as perceived by six teacher educators from three Danish university colleges?

What methods do these educators employ to enhance their students’ cultural competence?

How do these methods resonate with the theoretical principles of critical multiculturalism and multicultural education?

In the context of this paper, cultural competence is defined as teachers’ ability to understand, respect, and actively integrate cultural and linguistic diversity into teaching practices, aiming to establish empowering learning environments.

This study provides a critical analysis of Danish teacher education, offering valuable insights relevant both within the domestic context and for international educational stakeholders. This relevance is substantiated by the study’s alignment with global research trends concerning cultural and linguistic diversity in education.

The study’s theoretical framework builds upon critical multiculturalism as conceptualized by May and Sleeter (2010). In the educational context, critical multiculturalism diverges from trivialized multicultural education by not merely promoting awareness and appreciation of cultural diversity but also seeking to interrogate the underlying power structures that perpetuate inequities among different cultural groups (May & Sleeter, 2010; Vavrus, 2010). By employing a lens of critical analysis to scrutinize systemic inequalities, critical multiculturalism encourages both teachers and students to challenge and transform oppressive systems of power (May & Sleeter, 2010; Vavrus, 2010). Hence, it aims for a more comprehensive and transformative impact on educational settings.

When it comes to the practical implementation of the theory of critical multiculturalism, Skrefsrud (2022) critically examined the underpinnings of multicultural education and concluded that it is a multifaceted concept which should not be narrowed down to a single approach. This perspective challenges traditional Eurocentric curricula by advocating for a more inclusive educational system. Aligning with May and Sleeter (2010), Skrefsrud (2022) also highlighted the pitfalls of trivialized multicultural education practices that lack integration into everyday school activities, arguing that such isolated approaches can be counterproductive and may perpetuate existing structural inequalities. This argument is supported by Dervin (2023), who discussed the general reluctance among teachers to address issues related to power and social justice, largely due to the lack of confidence and fear of being labelled as troublemakers by other school personnel. The matter is further complicated by the imprecise and often problematic use of terms such as ‘ethnic’ and ‘cultural’, which can lead to stereotyping and treating minority students as spokespersons for ‘their culture’ (Dervin, 2023).

Borrero et al. (2018) add another layer to this discussion by investigating the constraints teachers face in implementing culturally relevant pedagogy, which is a pedagogical approach introduced by Ladson-Billings (1995). Culturally relevant pedagogy aims at empowering students academically and socially by actively integrating their cultural backgrounds into the educational process (Ladson-Billings, 1995). The study by Borrero et al. (2018) indicates that administrative demands often hinder teachers’ abilities to engage in culturally relevant pedagogy. Moreover, a lack of peer support and the absence of established curricular models further discourage teachers from adopting more holistic, culturally relevant strategies (Borrero et al., 2018).

In the Danish context, various studies explored the practical implementation of multicultural education, focusing on linguistic and cultural minority students. For instance, Steffensen and Kjeldsen (2021) criticized Danish curriculum documents for the lack of a comprehensive understanding of culture, suggesting that its pedagogical discourse tended to overlook the cultural diversity present among students, thus enforcing colour-blind views. A study conducted by Frederiksen et al. (2022) indicated that ethnic minority schoolchildren faced academic challenges and lacked scaffolding. Moreover, their findings revealed that the teachers predominantly adopted monocultural deficit-based perspectives on their students while positioning ‘Danish culture’ as the norm (Frederiksen et al., 2022). Both studies called for a more nuanced and holistic approach to multicultural education in Danish schools. This can be achieved by, for instance, viewing children’s diverse cultural and linguistic resources as assets and prerequisites for learning that enrich their educational experience (Martin & Pirbhai-Illich, 2019).

Different ways of promoting multiculturalism and critical thinking were researched and discussed in the international literature. Dunn et al. (2022) described a creative approach to fostering an empowering learning environment by designing activities focused on helping youths of colour from urban communities articulate their experiences with discriminatory narratives. Particularly innovative was a ‘hacking’ project, where students were tasked with transforming a social injustice into visual counternarratives while critically reflecting on the value of their voices and experiences. Through these counternarratives, the students revealed a disconnect between governmental promises and lived realities (Dunn et al., 2022). This underscored the importance of an education rooted not solely in theory but in students’ lived experiences and critical perspectives.

Regarding assessment in multicultural classrooms, the existing literature underscores the significance of adopting holistic assessment methods that incorporate diverse approaches, including peer, group, and self-assessment (Brookhart & Nitko, 2019; Kirova & Hennig, 2013). Specifically, language portraits are recognized as an effective self-assessment tool that facilitates the exploration of an individual’s linguistic identity. Conceptualized by Busch (2012), language portraits serve as visual representations that plurilingual individuals create to depict their linguistic repertoire. They illustrate the array of languages an individual interacts with and the specific contexts in which these languages are utilized.

Teacher education plays a significant role in equipping future teachers with the necessary practical skills to implement culturally relevant pedagogy and to create and sustain empowering multicultural school environments (Carter Andrews, 2021; Ladson-Billings, 2021). Abel (2019) and Navarro et al. (2019) call for a substantive transformation in teacher education programs, moving from a superficial commitment to diversity toward actively disrupting systems of inequity. This can be achieved by active involvement in critical discussions about the positions of minority groups within dominant society. Maloney et al. (2019) argue for transformative teacher education that builds meaningful relationships with communities, thus echoing the need for a praxis-oriented approach. This conveys the imperative for not only teacher education programs but also practicing educators to continually engage in critical reflection and community collaboration as a route to social justice in education (Maloney et al., 2019).

Andrzejewski et al. (2019) emphasized critical collaborative work and knowledge exchange as necessary strategies in multicultural teacher education. To have an empowering effect, such collaboration should extend beyond faculty to include students, thereby breaking down traditional hierarchies and facilitating a more dialogic learning environment. This approach involves embracing teaching as a humanizing and holistic approach, recognizing and challenging power dynamics (Andrzejewski et al., 2019). Nevertheless, in reality, multicultural education courses within teacher education curricula continue to fall short of adopting a critical orientation, opting instead for conservative or liberal perspectives centred on simple diversity appreciation (Gorski & Parekh, 2020). The absence of in-depth critical engagement with multiculturalism could compromise the empowerment of future teachers, who need to experience such nuanced understanding to effectively incorporate it into their own pedagogical approaches (Carter Andrews, 2021; Ladson-Billings, 2021).

In summary, critical multiculturalism diverges from the theoretical framework of multicultural education. Although multicultural education offers a promising avenue for fostering inclusivity and equity, its practical implementation is fraught with challenges. These challenges range from the superficiality of poorly integrated interventions to constraints imposed by administrative requirements and a lack of resources or support for school personnel (Borrero et al., 2018; Ladson-Billings, 2021; Vavrus, 2010). Thus, critical multiculturalism, as argued by scholars like May and Sleeter (2010), offers a foundation for interrogating these issues in a more comprehensive manner. It seeks to not just insert diversity into existing power structures but to fundamentally transform them.

This study employs a qualitative research approach, utilizing dyadic interviews as its primary method for data collection. Dyadic interviews are an effective mechanism for gathering rich and nuanced data, facilitating interaction between a researcher and two participants, thereby allowing them to reflect upon and critically engage with each other’s perspectives and experiences (Morgan, 2015). This active interaction often leads to the introduction of topics that might otherwise remain unexplored in individual interviews. Previous research by Lobe and Morgan (2021), which compared the efficacy of dyadic interviews with focus groups, found that participants and researchers generally felt more comfortable in dyadic settings. Furthermore, dyadic interviews offer pragmatic advantages compared to focus groups, particularly in participant recruitment and scheduling. These logistical benefits enhance the feasibility of the research process, making dyadic interviews not only academically robust but also a pragmatic choice for qualitative inquiry.

Given that the study was conducted by a researcher based in Norway, it underwent evaluation by the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research. The agency concluded that the study’s handling of personal data complies fully with all relevant data protection legislation.

Denmark has a total of six university colleges with multiple campuses throughout the country. These university colleges offer four-year teacher education programs designed to prepare student teachers for careers in Danish compulsory schools [Danish: folkeskole], which encompass both primary and lower-secondary education. The teacher education curriculum is highly organized and divided into distinct modules that are largely predetermined by the Ministry of Higher Education and Science. These modules cover general pedagogical competencies as well as subject-specific expertise, reflecting the subjects taught in compulsory schools. Students are normally required to choose three school subjects as their specializations (Ministry of Higher Education and Science, 2023).

Since the study’s objective was to explore teacher educators’ perspectives on ways to enhance students’ cultural competence, the initial step in participant recruitment involved reaching out to the international offices at all six university colleges. The researcher’s request was to distribute a call for participation to teacher educators facilitating subjects on bilingual education, foreign language instruction, or teaching Danish as a second language. Three university colleges agreed to participate in the study. The recruitment target was six teacher educators in total – two from each participating university college. This objective was achieved, facilitating a balanced representation across the institutions involved.

All six participants in the study are female teacher educators with over five years of experience in the field. They identify themselves as ethnically Danes, having Danish as their first language. Their specific areas of interest include multicultural education and cultural diversity. The participants have experience facilitating subjects on bilingual education, foreign language instruction, and/or teaching Danish as a second language. This wealth of expertise adds a layer of depth and nuance to the study, enriching the data collected and their subsequent analysis.

The teacher educators were invited to participate in dyadic interviews conducted via video conferencing software. Each participant took part in one dyadic interview. In total, three interviews were conducted with six participants. Prior to the interviews, they were provided with an information sheet and a consent form, both written in Danish. They were also encouraged to pose any questions they might have regarding the study and their participation in it. By signing the consent form, the participants agreed to be audio-recorded during the interview. The interviews were conducted in Danish by the researcher (author of this paper). Table 1 provides information on the interviews and includes pseudonyms for the participants involved in each session.

Table 1

Interview information

|

Interview |

Interview duration (min) |

University College |

Participants’ pseudonyms |

|

Dyadic interview 1 |

39 |

University College A |

Veronika, Vibeke |

|

Dyadic interview 2 |

37 |

University College B |

Kirsten, Karen |

|

Dyadic interview 3 |

39 |

University College C |

Ursula, Ulrikke |

The interviews were guided by a semi-structured interview guide with open-ended questions designed to prompt discussion between the participants (Braun & Clarke, 2013). The interview guide was developed based on the literature review, ensuring the questions were grounded in the research objectives. Echoing techniques commonly employed in group interviews, the researcher facilitated the discussion but allowed the participants to lead the conversation, encouraging interaction between the pair to elicit natural, co-constructed responses (Morgan, 2015; Smithson, 2000). The dyadic nature of the interviews created a dynamic atmosphere of opinion sharing and reflection on the interview topics. During the interviews, the researcher remained attentive to the dynamics between the participants, subtly steering the conversation to cover all relevant topics while allowing a space for free discussion.

Data Analysis

The audio recordings of the interviews were transcribed verbatim. During the transcription phase, the participants’ names were substituted with the selected pseudonyms to protect their anonymity. As presented in Table 1, the pseudonyms assigned in this study were Veronika, Vibeke, Kirsten, Karen, Ursula, and Ulrikke. Quotations cited in the findings section were translated into English by the author of this paper. Efforts were made to ensure that the English translations adhered as closely as possible to the original Danish text. These efforts included engaging a colleague to review the translations, followed by a back-translation to verify the alignment with the original meanings.

The interviews underwent a thematic analysis, as delineated by Braun and Clarke (2013). ATLAS.ti software was utilized to manage the data throughout the entire analytical process. Initially, the interview transcriptions were subjected to close reading, during which annotative observations were made to identify the main topics in the interviews. These observations facilitated the construction of a codebook that was subsequently employed to code the data. Following this, a full-coding approach was utilized which involved the use of both researcher-derived codes and data-derived codes. The former were developed based on theoretical considerations and a literature review. The latter emerged from patterns identified through a detailed examination of the transcriptions, where recurring or significant concepts were formulated as codes and subsequently added to the codebook. After completing the coding process, the codebook was reviewed and refined. This review involved evaluating each code for its relevance and applicability by comparing them against the transcriptions and checking for consistency in code application. Codes sharing thematic commonalities were then grouped into categories and subsequently brought together to form themes.

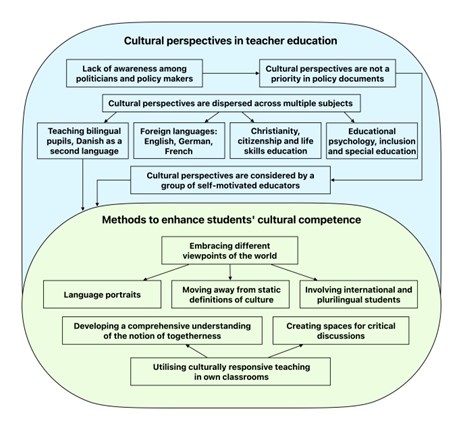

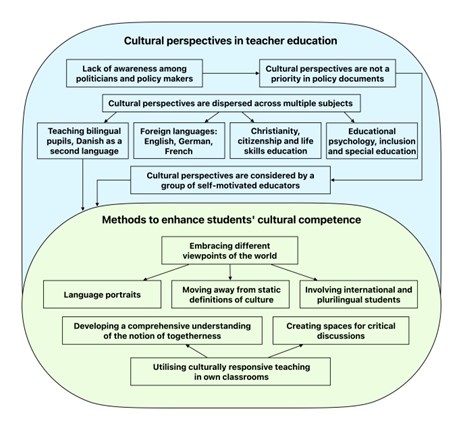

For the objectives of this paper, two interrelated themes have been selected: Cultural perspectives in teacher education and Methods to enhance students’ cultural competence. The theme of Cultural perspectives in teacher education included categories that presented different aspects of how cultural issues are recognized, discussed, and integrated within teacher education programs. This theme encapsulated data related to curricular content, educator attitudes, and institutional policies. The theme of Methods to enhance students’ cultural competence included categories that illustrated specific strategies, pedagogical approaches, and programmatic initiatives aimed at enhancing students’ cultural competence. To increase the conceptual clarity of the themes, a visual representation was developed in the form of a content network, which illustrated the content of the themes and their interconnections. Figure 1 displays this content network and presents the outcomes of the analytical process.

Figure 1

Teacher educators’ reflections on cultural perspectives in teacher education and methods used to enhance students’ cultural competence

During the interviews, the participants reflected on the place of multicultural education within the context of teacher education in their respective university colleges. Furthermore, they shared a range of methods and strategies they utilized to enhance students’ cultural competence. All participants underscored the importance of systematic integration of cultural perspectives in teacher education to prepare future teachers to better accommodate the needs of children from diverse cultural backgrounds in Danish compulsory schools.

This section presents findings related to the participants’ reflections on the place of cultural perspectives in policy documents concerning teacher education, the integration of cultural perspectives across various subjects, and the continual shifts in the subject of Danish as a second language.

Cultural Perspectives in Policy Documents

When contemplating the place of multicultural education and cultural perspectives within teacher education, the participants emphasized that both were challenging to define due to the ever-changing nature of the Danish policies governing teacher education. Overall, they pointed out a lack of awareness among politicians and policymakers of the importance of integrating cultural perspectives into teacher education. The participants emphasized that the absence of clear guidelines and objectives for fostering student teachers’ cultural competence exacerbates this issue. For instance, Kirsten explained this by saying:

When it comes to cultural competence, the students have few opportunities to develop it. However, there is no need for it based on what is written on paper. And there have been some political movements in Denmark in recent years that have influenced the development of teacher education and what is considered necessary in teacher education. It has been decided, for instance, that technology is important and essential in teacher education. So, it becomes necessary to make room for it. And culture may be one of the areas that is deprioritized in this context.

Kirsten’s statement reveals how educational policies may reinforce existing cultural hierarchies by failing to systematically integrate cultural perspectives. She highlighted the issue of accountability, implying that without appropriate attention to cultural competence, this topic might end up being side-lined.

Integration of Cultural Perspectives across Various Subjects

According to the participats, although some traces of cultural perspectives can be found across various subjects within teacher education, they are mainly introduced to students specializing in foreign language teaching (i.e., English, German, and French). However, the participants expressed concern that the current approach to integrating cultural perspectives in these subjects is notably narrow. As an illustration, they shared that in courses designed for preparing English language teachers, there is a pronounced emphasis on literature from American and British sources. Veronika, who taught a module for future English language teachers, illustrated this point by sharing:

For example, the students who specialize in teaching English mostly read American or British texts. Sometimes, I include texts from other English-speaking countries. But really, we [educators] should be doing this consistently to make sure our students actually bring this knowledge into their classrooms.

The participants pointed out that the subject of Christianity, citizenship, and life skills education might incorporate certain cultural perspectives when discussing aspects such as upbringing, socialization, and identity formation. However, Karen explained that the depth of exposure to cultural perspectives varies depending on the specific interests of each individual educator:

Cultural perspectives are sometimes included in subjects such as KLM [Christianity, citizenship, and life skills education – Danish: Kristendomskundskab, livsoplysning og medborgerskab]. But it depends on who is teaching the subject. If the educator is interested in culture or multicultural education, [they] may include it in KLM. But it is totally up to them, it is not required.

Additionally, the participants pointed out that cultural perspectives are incorporated within the subject of Educational psychology, inclusion, and special education. However, similar to the situation described by Karen, the depth of integration of these perspectives varies depending on the individual educator.

Continual Shifts in the Subject of Danish as a Second Language

The participants noted that the most attention to cultural perspectives is given within the subject of Danish as a second language. However, they have witnessed significant changes and transformations in this subject over the course of their professional careers, including name changes between Danish as a second language and Teaching bilingual pupils, as well as adjustments in the ECTS credit value (ECTS referring to the European Credit Transfer System). Ulrikke pointed out how the decision-making process surrounding the subject’s development and adjustments is heavily influenced by politicians, who often possess limited knowledge of teacher education and follow the prevailing political agenda. She summarized these continual shifts:

In the old days there was Danish as a second language as an elective teaching subject. It dealt with the entire field – culture, language acquisition, language pedagogy, language assessment, etc. Then it became a compulsory subject [Teaching bilingual pupils] worth 10 ECTS credits as part of the general pedagogical competencies. So, now we have both a compulsory subject and an elective one. But the compulsory one was reduced to 5 ECTS credits, which meant cutting out a lot because you cannot fit everything into one semester. It is a political decision. But let’s be honest, politicians don’t really understand what goes on in teacher education and what teachers need to know nowadays. So, they just mess around with the number of credits.

The participants also underlined that the subject has never included a comprehensive examination of cultural diversity in the context of compulsory schooling, nor has it focused on equipping students with knowledge of culturally relevant pedagogy and assessment methods. Instead, developing students’ knowledge of second language teaching methods has always been the primary objective. Similar to the subject of Christianity, citizenship, and life skills education, the integration of multicultural education and cultural perspectives is, according to the participants, systematically undertaken only by a small group of self-motivated educators. This situation potentially leaves many students at risk of completing their education without receiving training on working with children’s cultural diversity. Vibeke encapsulated this by saying:

There is a very big discussion about whether you should work with multicultural education. And we have colleagues who don’t do it at all, who only talk about language in that subject [Danish as a second language]. And then we have others who insist on working with multicultural education, even though it is not part of the learning objectives. I personally think that you cannot work with language and plurilingualism without working with multicultural education. That is where I want to start every time.

The participants also observed that the subject of Danish as a second language (previously Teaching bilingual pupils) was the only chance many students had to encounter the ideas of multicultural education. Hence, equipping them with holistic theoretical knowledge and practical skills within the relatively short timeframe of the subject, typically spanning several months, presented a considerable challenge for the participants. Despite these challenges, they remained dedicated to enhancing students’ cultural competence and employed various methods to do so, which will be presented under the second theme found in the data analysis in the following section.

This section presents findings related to the second main theme encapsulating the participants’ reflections on the diverse methods they employed to enhance student teachers’ cultural competence. These methods include fostering a holistic understanding of culture, differentiating between intercultural and multicultural concepts, employing language portraits, leveraging diversity within teacher education, creating spaces for critical discussion, and exploring the notion of togetherness.

Fostering a Holistic Understanding of Culture

The participants were highly positive toward the tenets of multicultural education. They firmly believed that integrating cultural perspectives into their teaching practices is essential for developing their students’ cultural competence and equipping them for future work with children from diverse cultural backgrounds. However, one of the participants’ main challenges was fostering a holistic understanding of culture among their students. They observed that students often enter their classrooms with a narrow and static perspective on culture, associating it solely with factors such as nationality, ethnicity, race, or language. Vibeke, who taught a module for future French language teachers, expressed the concern that some learning materials contribute to this static understanding of culture:

It is challenging with language-related subjects because textbooks often present a classic and static view of culture. For example, they depict school and life in France as being fixed in a particular way. Incorporating a modern view of culture within a textbook context is very difficult.

Therefore, the participants considered expanding students’ views on culture beyond fixed stereotypes and generalizations as crucial, as necessary to developing students’ cultural competence.

Differentiating between Intercultural and Multicultural Concepts

Another challenge faced by the participants in their teaching practices was addressing students’ confusion regarding terms such as intercultural and multicultural. While the participants acknowledged that there is an ongoing debate about potential differences in terminology, they explained that these terms are used interchangeably within the context of the teacher education program in their respective university colleges. During the interview with Ursula and Ulrikke from University College C, a discussion on the choice of terminology emerged. Ulrikke contributed to this topic by stating:

Differences between inter- and multicultural in the long run depend on whom you read. I think more that it is a question of discourse – what kind of definition lies behind the different terms rather than that there is actually a difference in the meaning of the terms. I don’t think there is a discrepancy between the terms as such.

While Ulrikke was speaking, Ursula nodded in agreement and eventually shared her own thoughts:

I think there is a tendency to use them interchangeably here. I have a feeling we [educators] do not distinguish. And I do not think students do. Like once in a while when there are some conversations about [these terms]. Otherwise, they are used interchangeably.

Overall, the participants stressed the significance of equipping students with a more nuanced and dynamic understanding of culture, prioritizing the embracement of different worldviews over engaging in theoretical debates about terminology.

Employing Language Portraits

The participants from University Colleges A and B viewed language portraits as a powerful method to embrace different viewpoints and promote active knowledge exchange in multicultural classrooms. Veronika explained that she developed an activity for her students that was linked to their on-site training in schools. This activity involved the student teachers creating language portraits for themselves and guiding their pupils to create theirs. Later, the student teachers had to present and discuss the portraits in Veronika’s class. She described the exercise:

I always focus my students’ attention on how important it is to understand children’s language repertoires. One activity I use involves sending them out to schools to create language portraits together with children. This helps them understand children’s language repertoires and reflect on their own. When they come back to my class, they share their experiences. It has been both fun and good exercise that broadens their [student teachers’] views on linguistic diversity.

By introducing the concept of drawing language portraits, the participants aimed to give student teachers a creative means to express their linguistic backgrounds and to reflect on the linguistic diversity among children in schools. Furthermore, by sharing their experiences with their peers, student teachers were able to involve themselves in discussions about how language portraits can serve as a useful self-assessment tool within educational settings.

Leveraging Diversity within Teacher Education

The student body at the participating university colleges mirrored the cultural diversity of Danish society. This diversity was considered by the participants as an invaluable asset that deserves greater recognition. They believed that the diverse student population possesses unique perspectives, experiences, and knowledge that have the potential to enrich the learning environment and contribute to the overall quality of teacher education. During the interview with participants from University College B, Karen posed several rhetorical questions:

In the teacher education program, we have a diverse classroom. We have minority and majority ethnic students. We [educators] have discussed multiple times about what we do ourselves as teachers. How should we approach our classrooms? How do we establish relationships with our students? How can we incorporate more multicultural education into our own teaching to become role models? We could do much more. But these discussions tend to arise periodically and then fade away again.

In her quote, Karen is alluding to student cultural resources not being incorporated into the teacher education program in a systematic manner. In the interview at University College A, Veronika echoed similar concerns. She argued that instead of merely presenting the theory of multicultural education, educators should provide student teachers with hands-on experiences and opportunities to actively engage in culturally relevant teaching:

We [educators] did small exercises on how to implement multicultural education. My experience is that when they [students] are presented with approaches, activities, and assessment forms, they tend to want to try them. And as soon as we [educators] use these methods in our own teaching and the students experience them first-hand, they tend to really want to go ahead with them.

Veronika later elaborated that she aims to serve as a role model for her students, demonstrating that it is possible to employ a variety of teaching methods and to capitalize on the cultural and linguistic diversity present in the classrooms.

Creating Spaces for Critical Discussion

The participants from University College B shared a story about a group of motivated students and academic staff who took the initiative to establish a critical discussion club focused on addressing various forms of discrimination within teacher education, including diversity-related issues. The primary objective of this group, they noted, is to foster an environment where every student feels valued and to explore ways to enhance critical perspectives within the field. Kirsten described the group as follows:

On a positive note, there is a group of both students and teachers who have set up what they call a norm-critical forum – as a meeting space. They are interested in, among other things, supporting more norm-critical views in general and finding a way to make [University College B] more inclusive.

During the interview at University College A, Veronika mentioned that she, along with her colleagues, facilitated a series of workshops for student teachers. These workshops aimed to create spaces for discussions, as they required student teachers to work in groups to reflect on various issues related to multicultural education. Veronika explained:

In the module on teaching bilingual pupils, we facilitated a series of workshops – a social media workshop, a workshop about mother-tongue education, a workshop about refugees, and a workshop about family-school cooperation. The students mainly worked in groups and presented the results of their group work. I have a feeling that these workshops were quite effective.

However, echoing previous findings, the participants noted that the initiatives, such as discussion groups and workshops, are inconsistent in terms of frequency and lack implementation at the institutional level.

Exploring the Notion of Togetherness

The notion of togetherness was also discussed during the interviews. The participants revealed that togetherness holds great importance within the context of teacher education, since compulsory schools are regarded as key institutions for fostering a shared sense of community and unity. Furthermore, they revealed that compared to multicultural education, the notion of togetherness is more prominently emphasized within Danish teacher education, and students generally demonstrate an awareness of its significance. For instance, Ulrikke mentioned that teacher educators at University College C devote considerable time to discussing the notion of togetherness with student teachers:

We talk a lot about the notion of togetherness. And we talk about public schools as community-building institutions, and that public schools are in some way a place to develop a sense of belonging. So, we spend much time discussing various methods to facilitate togetherness within school environments.

In the same interview, Ursula expressed some skepticism about how the concept of togetherness is presented in teacher education. She voiced concerns over the lack of critical perspectives on this topic, especially regarding its application in contemporary Danish schools:

I hope they [students] really think about it when they say togetherness. However, I almost think that it is something that is implied in teacher education, and they [students] take it nearly mindlessly without being critical of what we mean when we talk about togetherness. And how much space do we have in our so-called togetherness? If it is a narrow togetherness. Is there space for diversity?

At the end of the interviews, the participants were prompted to consider potential changes in the teacher education program to elevate cultural perspectives. In response, they emphasized that merely adding ECTS credits or incorporating additional subjects on cultural perspectives in education would not be sufficient. Karen advocated for a holistic approach that entails systemic changes and a fundamental shift in the underlying mindset of the program:

It is the entire system that needs to be reformed. I do not think that it would make a big difference if we had five subjects about multicultural education. There is more that needs to be done. There must be a more systematic approach to integrating multicultural education in teacher education to really have an impact.

In summary, the findings from this study suggest that Danish teacher education predominantly adheres to a monocultural framework, with the integration of multicultural education occurring sporadically and largely dependent on the initiative of individual teacher educators, such as those participating in this study. Despite the constraints imposed by the monocultural policies concerning teacher education, the participants discussed various methods and strategies they employ to enhance their students’ cultural competence. The participants primarily concentrated on cultivating a dynamic understanding of culture among their students by incorporating authentic learning materials and facilitating workshops and discussions, whilst adapting their work in the face of the monocultural reality.

The analysis of the interviews revealed two interrelated themes, which encapsulated the views of the participating teacher educators on the place of cultural perspectives in teacher education in their respective university colleges. Furthermore, this paper elaborated on the methods and strategies the participants employed to enhance their students’ cultural competence.

Overall, the participants pointed out the lack of awareness among politicians and policymakers of the importance of cultural perspectives, which manifests in the unclear status of multicultural education in the documents regulating teacher education. The continuously changing policies and regulations add a degree of uncertainty and inconsistency that hinders teacher educators’ ability to establish a clear focus and formulate reliable strategies to successfully incorporate cultural perspectives in their classrooms. This challenge is further exacerbated by the prevailing Eurocentrism within teacher education, as illustrated by the participants who pointed out the lack of cultural diversity in the current contents of Danish teacher education curriculum.

The literature on multicultural teacher education highlights the issue of unexamined whiteness and privilege, wherein dominant cultural norms and perspectives are privileged at the expense of minority voices and experiences (Carter Andrews, 2021; Gorski & Parekh, 2020; May & Sleeter, 2010; Navarro et al., 2019; Vavrus, 2010). According to Gorski and Parekh (2020), teacher education programs often relegate multicultural education to isolated courses, which adopt a liberal or conservative stance, and focus predominantly on ‘appreciating diversity’ while bypassing the crucial aspect of fostering a critical orientation that prepares future teachers to confront and challenge educational inequities The implication of this limited approach is that it perpetuates existing systemic injustices and fails to address the discriminatory practices within educational institutions that affect minority groups (Gorski & Parekh, 2020; Vavrus, 2010). Therefore, it is urgent to critically examine and reform educational practices and policies to dismantle entrenched power structures, discriminatory discourses, and monocultural curricula. Such reform is necessary because it has the potential to confront the oppression and injustice that minority groups face due to the Eurocentric nature of schooling in Western societies. By advocating for a holistic approach to teacher education that includes systemic changes and a paradigm shift toward critical multiculturalism, educational institutions can achieve more substantial and enduring outcomes (Dixson, 2021; Gorski & Parekh, 2020; Ladson-Billings, 2021). These changes would not only help eradicate various forms of oppression but also ensure that cultural perspectives are not treated as additional or optional components but rather as integral aspects of teacher education.

During the research interviews, the study participants indicated that current teacher education in Denmark predominantly situates cultural perspectives within the domain of language teaching. However, they criticized positioning American and British cultural viewpoints and their respective linguistic variations as the standard, which tends to overlook other English-speaking cultures and global perspectives. Such a narrow scope neglects the opportunity to broaden students’ cultural understandings and fails to challenge the dominance of ‘traditional’ cultural narratives in English language education (Kubota, 2010).

When it comes to the subject of Danish as a second language (previously Teaching bilingual pupils), the study participants pointed out that the discussions about diversity within educational institutions are predominantly confined to language-related topics. This narrow focus not only limits the scope of discussions but also leads to generalizations and objectivizations of culture. Moreover, such an approach embodies essentialist views that are deeply rooted in Eurocentrism by simplifying complex cultural identities into fixed, homogenous categories, ignoring the dynamic and multifaceted nature of individual cultural experiences (Abel, 2019; Gorski & Parekh, 2020; Maloney et al., 2019; Navarro et al., 2019; Tavares, 2023). By perpetuating this simplistic view of culture, educational practices inadvertently reinforce systemic oppressions, further entrenching the power structures that privilege dominant cultural norms. In the context of critical multiculturalism, it is imperative to challenge these entrenched systems and advocate for a broader, more inclusive approach to understanding cultural diversity, one that transcends mere linguistic considerations and addresses the underlying social inequities embedded within educational policies and practices (Dixson, 2021; Gorski & Parekh, 2020; Ladson-Billings, 2021; Vavrus, 2010). As illustrated by Dervin (2023), many teachers still refrain from tackling issues of social inequities out of fear of being labelled as troublemakers or because they lack confidence in their own understanding of complex, culturally sensitive subjects. Therefore, it is essential for future teachers to be involved in critical discussions about topics that are politically or culturally sensitive (Dervin, 2023; Dixson, 2021; Ladson-Billings, 2021; Skrefsrud, 2022; Vavrus, 2010). By discussing these topics head-on, future teachers can be better empowered to challenge oppressive power structures and advocate for culturally relevant pedagogy (Ladson-Billings, 2021).

Despite the challenges related to the constraints imposed by the monocultural educational policies, the teacher educators in this study demonstrated a strong commitment to enhancing their students’ cultural competence, employing a range of pedagogical strategies. Moreover, their decision to participate in this study and share their insights can be viewed as an act supporting social justice. However, the success of their efforts is undermined by the lack of comprehensive, institution-wide support. As previously highlighted in this paper, integrating critical multiculturalism into teacher education will likely falter without robust institutional support. The urgency of implementing social justice initiatives is clear, yet their success still depends solely on the goodwill or discretion of individual educators. Therefore, this research aims not only to highlight the gaps in Danish teacher education but also to illustrate how the absence of institutional backing for critical multiculturalism impedes the potential impact motivated educators can have on enhancing students’ cultural competence. The study by Dunn et al. (2022) demonstrates that a holistic approach to program development is essential for incorporating critical perspectives and empowering students to reflect on the value of their own voices and experiences, thereby contributing to the transformation of dominant narratives.

The concept of togetherness holds significant relevance in a Danish educational context. It is rooted in the belief that individual enlightenment and a strong communal identity fostered through education are vital for societal well-being (Jantzen, 2020; Mason, 2020). Cultivating the ethos of togetherness has a potential to generate motivation “to act as both a recipient and contributor in the community of practice. This means that togetherness is an important key when it comes to creating meaningful and inclusive processes in schools” (Jantzen, 2020, p. 36). However, in the context of this study, the participants highlighted the necessity of investigating this notion more thoroughly. Specifically, they called for an exploration of the complexities and practical applications of togetherness within the contemporary context of multicultural classrooms. While acknowledging the importance of cultivating a sense of togetherness, the participants also emphasized how crucial it is to strike a balance between fostering a shared community spirit and creating an inclusive space for unique cultural backgrounds, experiences, and perspectives. Along these lines, the participants expressed skepticism regarding how togetherness is presented, raising concerns about the lack of depth and critical perspectives surrounding this concept.

As previously emphasized by Nielsen and Ma (2021), while it is valuable to foster a common spirit, the concept of togetherness should go beyond surface-level unity by critically engaging with questions of equity and social justice. This deeper engagement is imperative to examining and confronting the underlying power dynamics and discriminatory narratives that may exploit the concept of togetherness for exclusive purposes. In this context, Nielsen and Ma (2021) underscore that “any ‘togetherness’ education must be fluid and adaptable to changing contexts in order to prevent reductionism and, simultaneously, be strongly rooted in guiding ideals, values, and principles from which all pedagogy and practice is influenced” (p. 185). When student teachers are encouraged to think critically about the notion of togetherness, they can develop a deeper understanding of its limitations and potential pitfalls, enabling them to navigate the challenges and dilemmas that may arise in the future when working in multicultural school settings.

Finally, the participants in this study addressed a key aspect of teacher education, namely their role in serving as positive exemplars for a transformative change. For instance, they emphasized the need for embracing diversity within their university colleges and leveraging student teachers’ cultural backgrounds and resources, thereby illustrating the practical foundations of culturally relevant pedagogy. Within the literature on multicultural education, there is a compelling argument for a systematic integration of diverse cultures into educational contexts (Ladson-Billings, 2021; May & Sleeter, 2010; Nieto, 2010). Systematically integrating the diversity of student teachers has the potential to enrich the learning environment within teacher education programs and exemplify the promotion of equity in educational settings (Abel, 2019; Dunn et al., 2022; Navarro et al., 2019). This approach can serve as a model for student teachers to replicate in their future workplaces, thereby perpetuating a cycle of equity in education.

This paper emphasized the critical need for a stable policy framework that adopts a holistic approach to cultural diversity, transcending narrow perspectives on culture in contemporary educational settings. Previous scholarly works underscore that clear guidelines and emphasis on social justice in policy documents are important for facilitating a shift from a monocultural orientation to a critical multicultural orientation in teacher education (Carter Andrews, 2021; May & Sleeter, 2010; Vavrus, 2010). A holistic integration of cultural diversity across an entire teacher education program can benefit future teachers in developing the knowledge, competence, and skills necessary to navigate cultural complexities, challenge discriminatory discourses, and facilitate empowering educational experiences for all children.

The teacher educators in the study reported on in this paper emphasized that exposing students to different cultural perspectives is necessary to enhance their cultural competence. However, the current placement of cultural perspectives mainly within language-related subjects, together with constant amendments and readjustment of regulations, makes it difficult to draw clear pedagogical trajectories toward developing critical views on culture among students. Furthermore, as underlined by the participants, the depth of students’ exposure to cultural perspectives varies significantly between subjects, or even within a subject, depending on the specific interests of each individual educator. This brings attention to the absence of institutional accountability to invest in preparing future teachers to work in multicultural classrooms. It is also imperative for teacher educators, curriculum developers, and policy makers to acknowledge their crucial role in equipping future teachers with the knowledge required for successful engagement in multicultural environments, as this directly correlates with a meaningful commitment to social justice and equity.

Abel, Y. (2019). “Still going… sometimes in the dark”: Reflections of a woman of color educator. Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies, 41(4-5), 352-359. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714413.2019.1684163

Andrzejewski, C. E., Baker-Doyle, K. J., Glazier, J. A., & Reimer, K. E. (2019). (Re)framing vulnerability as social justice work: Lessons from hacking our teacher education practices. Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies, 41(4-5), 317-351. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714413.2019.1694358

Benediktsson, A. I. (2023a). Culturally responsive assessment in compulsory schooling in Denmark and Iceland - An illusion or a reality? A comparative study of student teachers’ experiences and perspectives. Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education, 7(2), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.5392

Benediktsson, A. I. (2023b). Navigating the complexity of theory: Exploring Icelandic student teachers’ perspectives on supporting cultural and linguistic diversity in compulsory schooling. International Journal of Educational Research, 120, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2023.102201

Borrero, N., Ziauddin, A., & Ahn, A. (2018). Teaching for change: New teachers’ experiences with and visions for culturally relevant pedagogy. Critical Questions in Education, 9(1), 22-39. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1172314.pdf

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research. Sage.

Brookhart, S. M., & Nitko, A. J. (2019). Educational assessment of students. Pearson.

Busch, B. (2012). The linguistic repertoire revisited. Applied Linguistics, 33(5), 503-523. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/ams056

Carter Andrews, D. J. (2021). Preparing teachers to be culturally multidimensional: Designing and implementing teacher preparation programs for pedagogical relevance, responsiveness, and sustenance. The Educational Forum, 85(4), 416-428. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131725.2021.1957638

Dervin, F. (2023). Interculturality, criticality and reflexivity in teacher education. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009302777

Dixson, A. D. (2021). But be ye doers of the word: Moving beyond performative professional development on culturally relevant pedagogy. The Educational Forum, 85(4), 355-363. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131725.2021.1957633

Dunn, A. H., Neville, M. L., & Vellanki, V. (2022). #UrbanAndMakingIt: Urban youth’s visual counternarratives of being #MoreThanAStereotype. Urban Education, 57(1), 58-82. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085918798065

Frederiksen, P. S., Løkkegaard, L., & Rasmussen, A. Ø. (2022). Etniske minoritetsdrenges læring i folkeskolen. CEPRA-Striben, 30, 42-53. https://doi.org/10.17896/UCN.cepra.n30.482

Gorski, P. C., & Parekh, G. (2020). Supporting critical multicultural teacher educators: Transformative teaching, social justice education, and perceptions of institutional support. Intercultural Education, 31(3), 265-285. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2020.1728497

Häggström, F., Borsch, A. S., & Skovdal, M. (2020). Caring alone: The boundaries of teachers' ethics of care for newly arrived immigrant and refugee learners in Denmark. Children and Youth Services Review, 117, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105248

Jantzen, C. A. (2020). Two perspectives on togetherness: Implications for multicultural education. Multicultural Education Review, 12(1), 31-37. https://doi.org/10.1080/2005615X.2020.1720136

Kirova, A., & Hennig, K. (2013). Culturally responsive assessment practices: Examples from an intercultural multilingual early learning program for newcomer children. Power and Education, 5(2), 106-119. https://doi.org/10.2304/power.2013.5.2.106

Kubota, R. (2010). Critical multicultural education and second/foreign language teaching. In S. May & C. Sleeter (Eds.), Critical multiculturalism: Theory and praxis (pp. 99-111). Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203858059-13

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 465-491. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312032003465

Ladson-Billings, G. (2021). Three decades of culturally relevant, responsive, & sustaining pedagogy: What lies ahead? The Educational Forum, 85(4), 351-354. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131725.2021.1957632

Lobe, B., & Morgan, D. L. (2021). Assessing the effectiveness of video-based interviewing: a systematic comparison of video-conferencing based dyadic interviews and focus groups. International Journal Of Social Research Methodology, 24(3), 301-312. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2020.1785763

Maloney, T., Hayes, N., Crawford-Garrett, K., & Sassi, K. (2019). Preparing and supporting teachers for equity and racial justice: Creating culturally relevant, collective, intergenerational, co-created spaces. Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies, 41(4-5), 252-281. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714413.2019.1688558

Martin, F., & Pirbhai-Illich, F. (2019). At the nexus of critical interculturalism and plurilingualism: Theoretical considerations for language education. Language Education and Multilingualism – The Langscape Journal, 2, 136-150. https://doi.org/10.18452/20616

Mason, J. (2020). Togetherness in Denmark: A view from the bridge. Multicultural Education Review, 12(1), 38-52. https://doi.org/10.1080/2005615X.2020.1720135

May, S., & Sleeter, C. (2010). Critical multiculturalism: Theory and praxis. In S. May & C. Sleeter (Eds.), Critical multiculturalism: Theory and praxis (pp. 1-16). Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203858059-4

Ministry of Higher Education and Science. (2023). Bekendtgørelse om uddannelsen til professionsbachelor som lærer i folkeskolen (BEK nr 374 af 29/03/2023). https://www.retsinformation.dk/eli/lta/2023/374

Morgan, D. L. (2015). Essentials of dyadic interviewing. Left Coast Press.

Navarro, O., Quince, C. L., Hsieh, B., & Deckman, S. L. (2019). Transforming teacher education by integrating the funds of knowledge of teachers of Color. Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies, 41(4-5), 282-316. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714413.2019.1696616

Nielsen, T. W., & Ma, J. S. (2021). Examining the social characteristics underpinning Danish ‘hygge’ and their implications for promoting togetherness in multicultural education. Multicultural Education Review, 13(2), 179-189. https://doi.org/10.1080/2005615X.2021.1919964

Nieto, S. (2010). The light in their eyes: Creating Multicultural Learning Communities. Teachers College Press.

Obondo, M. A., Lahdenperä, P., & Sandevärn, P. (2016). Educating the old and newcomers: Perspectives of teachers on teaching in multicultural schools in Sweden. Multicultural Education Review, 8(3), 176-194. https://doi.org/10.1080/2005615X.2016.1184021

Ozuna, C. (2022). To sider af samme sag: A comparative study of teacher education programs in California and Denmark. Journal of the International Society for Teacher Education, 26(1), 8-24. https://doi.org/10.26522/jiste.v26i1.3721

Ragnarsdóttir, H., Benediktsson, A. I., & Emilsson Peskova, R. (2023). Language policies and multilingual practices in Icelandic preschools. Multicultural Education Review, 15(2), 81-98. https://doi.org/10.1080/2005615X.2023.2250711

Skrefsrud, T.-A. (2022). Enhancing social sustainability through education: Revisiting the concept of multicultural education. In L. Hufnagel (Ed.), Sustainability, ecology, and religions of the world (pp. 1-16). https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.103028

Smithson, J. (2000). Using and analysing focus groups: Limitations and possibilities. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 3(3), 103-119. https://doi.org/10.1080/136455700405172

Steffensen, T., & Kjeldsen, K. (2021). Er kulturbegrebet danskfagets blinde vinkel? Et dokument- og casestudie af kulturforståelser i dansk og dansk som andetsprog. Acta Didactica Norden, 15(1), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.5617/adno.8080

Tavares, V. (2023). Teaching in diverse lower and upper secondary schools in Norway: The missing links in student teachers’ experiences. Education Sciences, 13(4), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13040420

Vavrus, M. (2010). Critical multiculturalism and higher education. In S. May & C. Sleeter (Eds.), Critical multiculturalism: Theory and praxis (pp. 19-31). Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203858059-6