A Teacher’s Perspective on Grit and Student Success in a High School Physics Classroom

Matthew T. Ngo, St. Francis Xavier University

Author’s Note

Matthew Minh Triet Ngo https://orcid.org/0009-0004-8282-486X

Correspondence concerning this article can be directed to Matthew Ngo at mngo@stfx.ca

Abstract

In a high school classroom, there are many factors that may influence academic achievement. One such factor may be due to the grit of individual learners. While much of the literature related to grit is focused on deficit ideological elements, structural elements, which are often overlooked, may also be present and could impact a student’s ability to be ‘gritty’ and successful in school. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to understand, from a teacher’s perspective, whether these structural elements, in addition to deficit elements, also impact student achievement. This autoethnographic study explores the culture of grit and student success in relation to three former students enrolled in Grades 11 and/or 12 Physics as they progress in their coursework. While deficit ideological elements exist within my autoethnographic narratives, structural ideological elements also implicate crucial moments when a student’s grit and success either radically improved or declined. Consequently, for those who support learners, the argument put forth in this paper suggests that being mindful of structural circumstances is essential if educators are to use grit to reinforce achievement.

Keywords: grit, student success, high school, physics, deficit ideology, structural ideology

A Teacher’s Perspective on Grit and Student Success in a High School Physics Classroom

As a high school Physics teacher, I have always been fascinated by students who, day in and day out, make incredible strides toward success. I am often left to wonder what elements and circumstances lead to academic achievement in students. Through much contemplation, early investigation and reflection, I discovered a phenomenon called grit. In the study informing this paper, I sought to investigate this construct to understand how it may enhance success in learners.

It is important for me to explain why I positioned grit as the focal point of this investigation. As a second-generation Vietnamese-Canadian, growing up was not easy. I was the eldest child in a poor, single-income family. Making friends and blending into society was difficult. Looking back, I believe it was likely due to the significant cultural differences between my at-home Vietnamese culture and that of the broader society. In addition to the differing culture, all the things associated with being poor (e.g., not wearing brand-name clothes or having money to attend social functions) also contributed to this difficulty. Sadly, for much of my childhood, I experienced hardships which negatively influenced my life. This negative influence made me doubt my abilities, self-worth, and my overall confidence. I did not believe I could amount to anything.

Throughout my childhood, education was the most dominant aspect of my life. Every day, my parents pushed me to excel. They believed that if I could sustain a high degree of academic excellence, I could one day escape poverty and have a promising future. While I was initially skeptical of this view, my parents instilled a belief in the importance of taking measured steps toward a larger goal. They believed that if I put in tremendous amounts of effort, I would experience success. Eventually, my dedication, persistence, and effort paid off; I was not only able to graduate high school, but I also maintained the mindset necessary to succeed at more challenging goals, such as graduating with a Bachelor of Science in Physics and Mathematics, completing a master’s thesis, and beginning a Doctor of Philosophy in Educational Studies.

In examining the phenomenon known as grit, I note that it is defined as passion and perseverance for long-term goals (Duckworth et al., 2007; Duckworth & Quinn, 2009). These scholars indicate that highly accomplished learners tend to have a high degree of grit. While much of the literature related to grit is connected to deficit ideological elements (Gorski, 2016, 2018; Kohn, 2014; Williams et al., 2020), there are often overlooked structural elements. For example, as a child, I was lucky to have two very involved parents who supported my education. While financial hardships existed, my parents made sacrifices to ensure we had the necessary money to buy notepads, calculators, or computers to be successful. However, not all families have the same privileges that I did, and consequently, this may also impact achievement. Therefore, such structural elements prove to be worthy of investigation when one intentionally utilizes the construct of grit to promote achievement in schools. As these educational scholars have identified, an overemphasis on grit can communicate that mindsets, personality, and attitudes are more important for success than the recognition of structural elements. In considering my own circumstances, if I did not have two involved parents who prioritized schooling, I do not believe I would have been at all successful. These structural elements may play a role for learners. Therefore, while one should not abandon the study of the concept of grit, the purpose of this paper is to understand how such structural elements, in addition to deficit elements, impact achievement.

In the following literature review section, I provide readers with an account of the ideological spectrum related to grit and student success. At one end of this continuum is deficit ideology, which positions itself on attributes such as mindsets, personalities, and motivation as factors for achievement. At the other end is structural ideology, which attributes achievement to elements such as social and familial structures, race, and income. While the study discussed in this paper examined these elements, it is conceivable that there are other significant elements at play.

The literature review presented here encompasses an overview related to the phenomenon of grit, which spans three main areas. The first section chronicles the notion of grit and its relationship to mindsets. This includes the exploration of Dweck et al.’s (1995) research related to entity and incremental theory. The second section describes the aspect of personality and motivation being embedded with grit. This includes the exploration of the Big Five factors and how certain personality factors may have relationships with an individual’s grit. It also includes the examination of Ryan and Deci’s (2000) research related to intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Finally, the third section illustrates how social and familial elements are related to grit. In addition to understanding the structural and deficit elements related to achievement, this paper reports on research that attempts to understand the phenomenon of grit and its impact on student success within a high school physics classroom.

Duckworth was originally a teacher who also wrote the 2016 book Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance. Duckworth wondered why some students were outperforming others. In trying to understand the reasoning behind this, she compiled the intelligence quotient (IQ) scores of her students and found that some of the top performers did not have the highest IQs; in fact, some of her best performers had lower IQs (Hochanadel & Finamore, 2015). Through further investigation, however, the one quality her highest performers did possess was grit (Duckworth, 2016).

Grit was a term coined by Duckworth et al. (2007) as passion and perseverance for long-term goals. An individual can persist and overcome challenges when faced with significant obstacles and barriers. Since the introduction of the term grit, a great deal of research has been conducted to determine its legitimacy (Datu, 2021). To measure grit, a numeric score is found by using a survey with a Likert scale, as reported by Duckworth et al. (2007) and Duckworth and Quinn (2009). After an individual completes the survey, results are averaged to determine an overall grit score. Since this groundbreaking research on grit, the phenomenon has received significant attention from both researchers and classroom teachers. The question remains, however, whether grit alone can support achievement within today’s classrooms.

One possible reason why certain individuals possess more grit than others may be due to their mindsets. In examining Duckworth et al. (2007) and Dweck et al. (1995), these scholars argued that it was not a lack of intelligence (lower IQ) that led students to failure but, rather, it was a lack of effort which caused some students to question their belief systems. As Dweck et al. (1995) identify, “people’s assumptions about the fixedness or malleability of human attributes predict the way they seek to know their social reality, as well as how that reality is experienced and responded to” (p. 282). It can be said that individuals who believe that they have fixed, non-malleable qualities of intelligence are bound by entity theory (i.e., fixed mindset). According to Dweck and colleagues, individuals who lean into entity theory, have a worldview that is relatively stable and predictable. However, for those who believe that intelligence is malleable and can be progressively changed, these individuals follow incremental theory (i.e., growth mindset).

Dweck et al.’s (1995) research illustrates that individuals with fixed mindsets tend to have less grit, less adaptability, and poor coping mechanisms. Such individuals are more likely to blame themselves for not being born more capable of achieving success. As Dweck and colleagues note, “this tendency towards global self-judgments is usually accompanied by a greater vulnerability to other aspects of a helpless reaction, such as negative affect, disrupted performance, or the abandonment of constructive strategies” (p. 275). In contrast, those who subscribe to a growth mindset, these authors believe that such individuals are more likely to attribute negative outcomes to a lack of effort and use strategies to overcome such situations.

Research from Duckworth et al. (2007) and Duckworth and Quinn (2009) identify the success of individuals as being tied to having a high degree of grit. Consequently, individuals with a high degree of grit tend to experience greater achievements. Examples include the prediction of first-year GPA scores (Akos & Kretchmar, 2017), a greater chance of success in graduating from high school (Eskreis-Winkler et al., 2014), higher test score gains in Mathematics and English Language Arts (West et al., 2015), a reduction in absenteeism (West et al., 2015), and excellent productive behaviours from fourth to eighth grades (West et al., 2015).

While these examples provide some indication of the value of grit and its probable implications for academic success, it is worth mentioning that Duckworth et al.’s (2007) and Duckworth and Quinn’s (2009) data were largely derived from specific populations. For example, Duckworth et al.’s investigation focused on cumulative grade point averages (GPA) among undergraduate students at an elite university; thus, such findings may not apply to those at non-elite institutions. Ivcevic and Brackett (2014) acknowledge this limitation in the work of Duckworth et al. (2007) and Duckworth and Quinn (2009) noting that participants were largely drawn from private schools and middle-class family backgrounds. Such a sample could obscure how socioeconomic status or systemic barriers may impact grit.

In Muenks et al. (2017), the researchers demonstrate the relationship between grit and personality theory. There are five main attributes that make up a person’s personality. According to Rimfeld et al. (2016), these Big Five factors are, “extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, openness, and neuroticism” (p. 780).

To define the Big Five factors, Caspi et al. (2005) describe those with extraversion to be expressive, energetic, and sociable. Such individuals have strong positive emotions. This can be contrasted with those who are introverted; that is, quiet and reserved individuals, seldom drawn to socialize. Those who have a high degree of agreeableness (the second Big Five factor) have positive traits such as cooperation, empathy, and politeness and are willing to accept other individuals’ points of view. This is contrasted with disagreeable individuals who are aggressive, stubborn, and set in their ways. Interestingly, as Caspi et al. (2005) and Poropat (2009) have identified, the personality traits related to openness are similar to those of extraversion and agreeableness.

Grit is found to be more closely affiliated with conscientiousness (the third Big Five factor) than the other factors (Duckworth et al., 2007; Poropat, 2009; West et al., 2015). Conscientious individuals are described by Caspi et al. (2005) and Poropat (2009) as being incredibly persistent and determined in their tasks, responsible, independent, and attentive. Other scholars have also identified conscientiousness, agreeableness, and low neuroticism (the fifth Big Five factor) as relevant factors for cultivating success (Noftle & Robins, 2007; Poropat, 2009). Interestingly, in Noftle and Robins’ (2007) research, these scholars identified their surprise, finding that openness (the fourth Big Five factor) was weakly related to academic performance for college students. This aligns with Poropat’s (2009) research, which found that openness and extraversion (the first Big Five Factor) have only minor effects on academic success.

Motivation is related to grit because individuals may be motivated by internal interest or by the desire for an external reward (e.g., social reinforcement or tangible prizes such as tokens or stickers) (Ryan & Deci, 2000; Von Culin et al., 2014). Ryan and Deci’s research (2000) outlines a range of factors that impact the motivation of individuals, including resistance, perceived control, disinterest, attitude, resentment, and a lack of acceptance of the value of a task. Individual differences in mindsets are one possible reason why individuals are either motivated or unmotivated (Poropat, 2009; Von Culin et al., 2014).

According to Radl et al. (2017), degrees of motivation vary based on an individual’s perceived locus of control, where “locus of control is the belief that life events are causally attributable to one’s own actions” (p. 221). Intrinsic motivation is defined as “the doing of an activity for its inherent satisfaction rather than for some separable consequence” (Ryan & Deci, 2000, p. 56). As these researchers describe, intrinsically motivated individuals act not for any instrumental reason but purely for the positive experiences gained from extending themselves further.

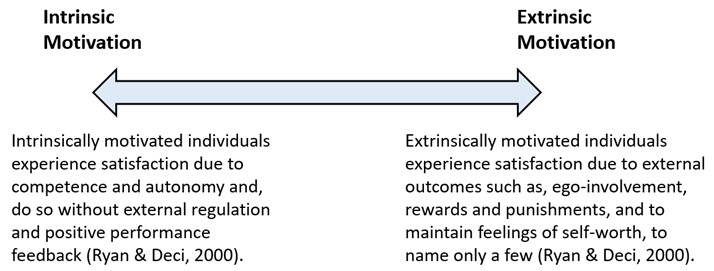

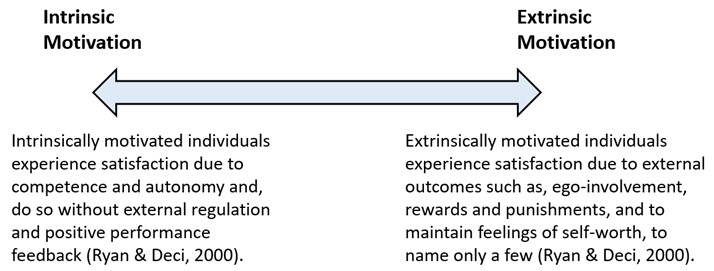

Figure 1

The Spectrum of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation (adapted from the work of Ryan and Deci, 2000)

Individuals with a high degree of intrinsic motivation experience satisfaction through competence and autonomy, and without external regulation or positive performance feedback (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Extrinsically motivated individuals differ because the performance of an activity is used to satisfy external outcomes such as ego involvement or rewards and punishments and to maintain feelings of self-worth, among other factors (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

Intrinsic motivation is related to grit because “intrinsic motivation [is] the inherent tendency to seek out novelty and challenges, to extend and exercise one’s capacities, to explore, and to learn” (Ryan & Deci, 2000, p. 70). This quote highlights the theme of grit. In examining Von Culin et al.’s (2014) research, these scholars showed that individuals who were extrinsically motivated were less gritty than their intrinsically motivated peers. While grit is important and has gained significant attention, as indicated in Duckworth et al.’s (2007) and Duckworth and Quinn’s (2009) research, it is equally important to consider that an understanding of structural elements, such as social and familial, needs to be considered as well.

Despite the advances and good intentions of many educational researchers studying grit, it would be imprudent to overlook the social, racial, and familial structures related to grit and the success of students. In today’s schools, students enter classrooms with unequal privileges and opportunities. These unequal power structures are sometimes overlooked or insufficiently examined.

In reviewing Gorski’s (2016, 2018) research, the author examines the social structures related to grit ideology. One prominent theme in Gorski’s research is the concept of meritocracy. Meritocracy is the belief that individuals are rewarded with opportunities based on their hard work, abilities, and talents rather than factors such as social class, family background, or wealth. It is the belief that regardless of one’s positionality in society, one could, through their efforts, end up becoming Prime Minister. This idea of meritocracy also extends to the student context, suggesting that students who can demonstrate hard work and considerable effort are able to achieve positive future outcomes (Carter, 2008). Unfortunately, research from critical educational scholars reveals that meritocracy is largely a myth (Apple, 2010; Cummins, 2021; Ladson-Billings, 2021).

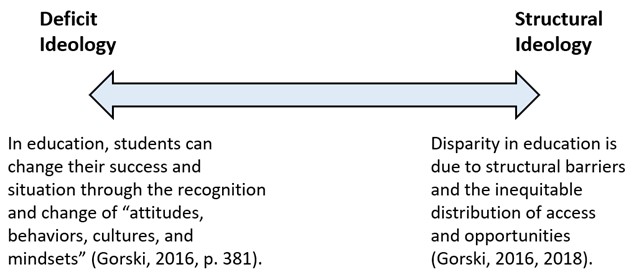

According to Gorski (2016, 2018), in a world of diverse educational ideologies, educators, policymakers, and researchers span different ideological spectrums. Gorski (2016, 2018) identifies deficit and structural ideologies as existing at two opposing ends of a broad spectrum, cautioning that they are not to be treated as binary concepts. For those in education who subscribe to a deficit ideology, there is a belief that students can change their success through recognition and change of attitudes, mindsets, and behaviours (Gorski, 2016, 2018), often overlooking or underestimating the significance of structural inequities. In a world marked by inequity and deeply rooted issues, such as unequal power structures, equal opportunity simply does not exist (Gorski, 2016, 2018; McIntosh, 2005). As a result, the term ‘equal opportunity’ serves only to obscure the existence of systems of dominance (McIntosh, 2005).

Figure 2

The Spectrum of Deficit and Structural Ideology (adapted from the work of Gorski, 2016, 2018)

As shown in Figure 2, structural ideology is on the opposite end of the spectrum from deficit ideology. Educators who identify more with structural ideology believe that disparity in education is due to structural barriers and the inequitable distribution of access and opportunities (Gorski, 2016, 2018). While there is recognition of structural barriers within Duckworth et al.’s (2007) and Duckworth and Quinn’s (2009) research, the questions asked in their grit test exclude aspects of poverty, instability, and structural inequities. With that said, and as Gorski acknowledges, when individuals overemphasize grit, “we tend to attribute a student’s underachievement to personality deficits like laziness” (Gorski, 2016, p. 383). Consequently, according to Gorski, grit ideology appears to lean more towards deficit ideology on the spectrum.

Students who identify as Black, Indigenous and/or People of Colour (BIPOC) are often at a disadvantage due to unequal power structures within a predominately White culture. The racism and other compounding oppression they face at the macro level of society are too often replicated at the micro level of the school. Unfortunately, the prevailing belief from politicians, policymakers, and researchers is that students can succeed and improve in school by focusing on changing mindsets, behaviours, and attitudes, and without significant and meaningful consideration of systemic and structural barriers (Gorski, 2016, 2018).

In examining immigrant and non-immigrant students in German schools, Hannover et al. (2013) showed that immigrant students who did not identify as part of the overall German school culture were not as successful as their native-born counterparts. The researchers describe the barriers to academic success as being deeply rooted in negative peer interactions, stereotypes in the school environment, and a vulnerability to discrimination. However, as evidenced by Hannover et al.’s research, students who can identify themselves within both ethnic and German cultures “outperformed students with purely ethnic school-related selves” (Hannover et al., 2013, p. 175). This may be due to what Carter (2008) identifies as effective cultural straddling. Students in school who are able to maintain and successfully negotiate between primary and secondary cultures while also affirming and reinforcing their cultural, ethnic, and racial identities, are likely to experience higher levels of academic success (Carter, 2008).

That said, the social environment and attitudes of people in schools are crucial for maintaining the success of students. Students who feel connected to their school and their fellow peers ultimately experience much more success because their social needs are met (Gore et al., 2016). In reviewing the work of Gore et al., the power of connectedness for all students is abundantly clear. Students who are able to form meaningful connections with other students, teachers, and staff, in addition to being actively involved in schools, have shown significant and positive academic results.

While some researchers have claimed that extroverted students tend to experience positive grade outcomes (Caspi et al., 2005; Noftle & Robins, 2007), new research is rethinking whether introversion is perhaps a more desirable quality (Cain, 2013). In Cain’s research, the scholar describes the different mindsets, motivations and personality characteristics between extroverted and introverted individuals. According to Cain (2013), society appears to have linked extroversion to success in different realms; however, introverted individuals are just as likely to be successful.

Educational performance, grit, and student success appear to be linked to poverty. Although poverty impacts all students from different backgrounds, social class intersects with race and racialized people are more likely to experience poverty. Therefore, this situation reinforces the need to consider how some students come to school with a certain set of privileges while other students come to school with few (or no) privileges. Thus, the concept of grit, without considering structural inequities, may be flawed (Gorski, 2016, 2018).

Family structures are also a major consideration when discussing wealth and poverty in today’s homes. Because family resources are finite, having many children in the household often reduces the financial resources available to each child (Radl et al., 2017). It is also common for children to be raised in lone-parent households. Frank and Fisher (2020) report, “children living in lone-parent families experience a much greater likelihood of living in poverty than children living in coupled families” (p. 24). Therefore, success can be seen as closely tied to income disparity, poverty, and family structures.

Theoretical Framework and Methodology

Here, I provide readers with a brief account of qualitative research and why I chose autoethnography as my methodology. I also believe it is crucial for researchers to reveal their positionality because not only do researchers have a direct influence on how they view, interpret, and construct the world (Mason-Bish, 2019) but the researcher’s use of language and how they pose questions are also linked to this positionality (Berger, 2015). Finally, I will provide readers with details on how I collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data.

Using Qualitative Research

Prior to conducting research for my master’s thesis, my methodological toolbox contained only quantitative approaches. As a physicist, my entire adult life was steeped in positivism. As a physics teacher, I once believed that the positivist tradition, in which quantitative research designs exist, was the gold standard for research (Denzin & Lincoln, 2011). When the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown occurred in March 2020, my research was put on hold. It was only in June of 2020, when I had a lot of time on my hands, that I decided to investigate whether other approaches could work for me. Fortunately, at that time, I was introduced to autoethnography, and I decided to adopt qualitative approaches for my research. That monumental decision opened a whole new world of epistemological ways of thinking. The seismic shift was not an easy one for me; however, over time and through deep reflection, I realized that quantitative and qualitative approaches have different merits for answering different research questions.

If researchers are attempting to ascertain statistical trends and patterns, they would lean on hypothesis testing and statistical treatments for data analysis. However, as Denzin and Lincoln (2011) have identified, if a researcher wants to understand how and why questions, qualitative methods shed new light on these questions. Rather than solidifying human experiences into numerical data, qualitative researchers focus on “understanding how people interpret their experiences, how they construct their worlds, and what meaning they attribute to their experiences” (Merriam, 2009, p. 5). Therefore, instead of doing research that aims to make generalized claims, I chose to use qualitative methods, specifically autoethnography, for my research design.

Why Autoethnography

Autoethnography originated as a merging of autobiography and ethnography (Adams & Ellis, 2012). According to these scholars, when an individual writes an autobiography, they retrospectively select and write past stories, assembling them using a recollection of memories. These researchers describe an ethnographer as someone who enters a defined culture for an extended amount of time. Such ethnographers use their observations and experiences, such as “repeated feelings, stories and happenings” (p. 201), to write a thick and vivid description of a culture (Geertz, 1973). Then, ethnographers often connect their experiences and findings to formalized research. Ultimately, as Adams and Ellis (2012) describe, ethnography aims to describe the cultural practices happening within an insider culture so that it becomes familiar to cultural outsiders. Because autoethnography exists at an intersection between autobiography and ethnography, it provides a medium for a researcher to draw upon their own experience, story, and self-narrative (Savin-Baden & Major, 2013) and to critically reflect on oneself in the context of a culture (Adams et al., 2015).

Regardless of one’s practice or genre of research, critical reflection is vital for a greater understanding of future practices and actions (Hamilton et al., 2008). As a teacher, I believe deep reflection is crucial for gaining long-term success. Deep reflection compels me to re-examine past assumptions, actions, and interpretations and whether different choices may have yielded different results. As addressed by Adams et al. (2017), rigorous self-reflection is typically referred to as reflexivity since it allows individuals to identify and interrogate the intersections between oneself and one's social life. To create an environment where all my students have the capacity to be successful, the constant need for my reflexivity is vital. At first glance, autoethnography gave me a positive impression due to its ability to help me sustain this practice. Additionally, as a researcher who shares cultural membership with cultural insiders, I aim to share my findings so that cultural outsiders (e.g., people whose identity is outside the classroom setting) can better understand, from a teacher’s perspective, what is happening within a high school physics classroom.

The draw to centre oneself within a defined culture also piqued my interest in autoethnography. This is because autoethnographic stories are stories positioned from an individual’s self through a cultural lens (Ellis et al., 2011). As Walford (2021) claims, the careful placement of the researcher at the centre of the research is helpful in arriving at a deep sense of understanding of oneself within a culture with others.

The positionality of a researcher is “where one stands in relation to the other” (Merriam et al., 2001, p. 411). Walford (2021) emphasizes the importance of identifying and clearly articulating one’s positionality and background when undertaking and publishing qualitative research. As this scholar asserts, without the identification of a researcher’s position and bias, a reader may not be able to critically evaluate a “researcher’s emotional, ethical, and personal dilemmas” (p. 34). Consequently, as Mason-Bish (2019) also affirms, not only do researchers have a direct influence on how they view, interpret, and construct the world but it is also linked to what Berger (2015) claims as the researcher’s use of language and how they pose questions.

As a second-generation Vietnamese-Canadian teacher, I had to tackle many different life circumstances. I lived a childhood where I had a misunderstood sense of classism, marginalization from a dominant society, social isolation, and other systemic structures that made it incredibly difficult for me to be successful. As noted earlier in this text, my family did not have money growing up, as we lived in a poor, single-income household. Yet, while I did not have much in the way of financial resources, my parents reinforced education as a way of escaping poverty. My success came from my parents’ continuous encouragement as they instilled in me a deep sense of determination and hard work.

Additionally, as a seasoned high school teacher, I share the cultural insider membership with the students that I teach. That is, these students attend the school where I teach, they come into my classroom, and they are involved with school functions. In other words, all these students interact with me on a daily basis. Therefore, I take ownership of these forthcoming stories as they are positioned within my classroom, and these stories are written through my lens and viewpoint. Such stories do not happen in isolation from me. It is important to recognize that my positionality has likely influenced my students and my decisions, as well as how I perceived certain events. Therefore, while the upcoming stories are centred on three students, their degrees of success were also influenced by my interventions, choices, and actions.

The purpose of this study was to understand whether the social and familial structural elements, in addition to deficit elements, also impact achievement and grit. Simply stated, I, as the researcher, was the primary participant in data collection (Savin-Baden & Major, 2013). As Adams and Ellis (2012) explain, an autoethnographic researcher retrospectively and selectively writes about their deep and meaningful experiences (i.e., epiphanies) that are made by being part of the culture through possessing a cultural identity (i.e., positionality).

Life experiences can be marked by significant events, and such events can be classified as epiphanic. Denzin (2014) describes an epiphany as a transformative moment of revelations that drastically alter the fundamental meanings of an individual’s psyche. These epiphanies are important because they “encourage us to explore aspects of our identities, relationships, and communities that, before the incident, we might not have had the occasion or courage to explore” (Adams et al., 2017, p. 7). Not all life experiences are epiphanic; some experiences may be aesthetic, since, as Bolen (2014) asserts, these insignificant moments may lack transformative power.

To conduct this autoethnographic research, I took the opportunity to deeply reflect upon the hundreds of students I have taught, as well as those with whom I had meaningful stories and experiences. Ultimately, I drew upon past epiphanic moments with three of them (using the pseudonyms of Caleb, Adhira, and Violet), as my experiences with these students not only drastically altered my understanding of the culture of grit and student success but also contained detail, the happenings and feelings that occurred at the time, even though some of these experiences happened quite some time ago. Recalling these epiphanic moments led me to share my personal narratives in the form of story, utilizing Denzin’s (2014) structure. Denzin depicts autoethnographic stories similar to those of performances. People are depicted as characters within a scene or context where the story is told in chronological order (Denzin, 2014). An epiphany or dynamic tension occurs between characters, which eventually leads to a point or moral of a story that gives meaning to an experience (Denzin, 2014). Consequently, to create these stories, I utilized Geertz’s (1973) notion of thick description. Drawing on these two sources was an intentional act on my part, as I wanted to engage readers by creating a sense of “being there in the moment” (Adams & Ellis, 2012, p. 3). Thick descriptions provide a sense of verisimilitude, making it feel ‘real’ to a reader and, in doing so, promote a deeper understanding of the stories and experiences being told (Adams et al., 2015).

Introducing the Students

In teaching Caleb, I recall that my experiences with him were negative. The two years that I taught Caleb were among the most difficult experiences I faced as a high school teacher. He came from a low socioeconomic, single-parent household. Through the daily behavioural issues and challenges, I often butted heads with him. Every day was a challenge, and often I felt let down because many of my interventions, such as building rapport, providing him with treats and rewards, or enforcing disciplinary consequences, failed. At some point, I gave up on him, and that was a difficult thing for me to do. However, when there is adversity, there is also often opportunity. During the height of the COVID-19 lockdown, he slowly changed his behaviours and, each day, worked very hard to be successful. He made it a point to overcome all odds and adversities in his life and, as a result, significantly turned around and ended up far exceeding his original goal of simply passing. What led him to this turnaround was important to my understanding of success.

In the past decade, I have taught many first/second-generation Canadians. I chose to write here about Adhira because, through our conversations, it seemed her upbringing closely resembled my own. Adhira was a very hard-working and determined student. She gave me every indication that she would be a gritty student. For example, she was always conscientious, ambitious, and self-motivated to succeed. Although she experienced a high degree of success, her success looked as if it was tied to her parents. At some point in Adhira’s Grade 12 year, her grades started to decline. She missed several classes, was inattentive in class, and often displayed a lack of focus on certain tasks. I originally believed it was what some Grade 12 students refer to as having ‘Senioritis,’ a feeling identified by students as having a lack of motivation because they were reaching the end of their high school experience. However, for Adhira, this was not the case. Adhira’s role as a translator, advocate, and support person for her parents was something I had not considered. Due to this role, many unknowns appeared to negatively impact Adhira’s schooling. For example, on the days she missed classes, I learned that she acted as a translator with doctors when her parents faced significant health concerns. This reality would appear to conflict with my initial assumptions about Adhira’s situation and, consequently, led me to consider the structural inequities that may exist behind the scenes. It was this reflection that led me to select Adhira as part of my research autoethnography. It is my view that parental expectations, students’ mindsets, and the relationships developed between the student, educator, and school have very profound impacts on student success.

When Violet first came into my class, she appeared to exhibit many signs opposite to grit. While she tried her best to be successful, she showed signs of agitation, anxiety, and stress when completing assessments, frequently expressing self-doubt and often becoming irritated by not remembering general concepts. It was Violet’s self-defeating words and attitudes that sometimes caused her to experience major setbacks in achieving academic success. Although it was likely unintentional for her to hold these self-defeating attitudes, they appeared to be linked to possibly unrealistic parental expectations that contributed to her negative sense of self. In other words, Violet’s success was not necessarily related to changing her own mindset and beliefs, but instead changing her mother’s mindset and beliefs around the idea of success. It was this change that ultimately led to Violet becoming one of my top Grade 12 Physics students. Overall, a major part of my understanding of grit and student success came from Violet. To this day, her difficult journey and her turnaround bring me great satisfaction. The experience demonstrates to me how her persistence and effort ultimately paid off in the end.

Data Analysis and Interpretations

To initiate the analysis of my stories, I began interpreting each epiphany and aesthetic event by assigning codes to the data. “Codes tend to be based upon themes, topics, ideas, phrases, and keywords” (Savin-Baden & Major, 2013, p. 422). I had a rationale for why I assigned codes to each event: Coding helped me sort clues and connections between each string of text, which would later allow me to compare and contrast during future interpretations and analyses. After I coded the entirety of the stories, I began the process of cutting, which Savin-Baden and Major (2013) refer to as snipping texts into small, meaningful segments. I looked at cues between these stories. Oftentimes, certain keywords stood out; other times, it was the similarities between the events. Based on this strategy, certain themes emerged. These themes included personality, motivation, perseverance, passion, cultural circumstances, familial structures, social structures, and income disparity.

As I continued the process of cutting, I noticed that most of the themes emerging in my data were also explored within the literature and discussed previously in the literature review of this paper. Essentially, as addressed by Adams and Ellis (2012), I connected my experiences from the narratives to the existing research and, in doing so, used the literature review to “interrogate the meaning of [the] experience” (p. 199). Therefore, the literature acted as a filter to support my interpretations; however, “the key [was] to ensure that these frameworks do not force interpretations but [merely] serve as a way to view them” (Savin-Baden & Major, 2013, p. 457). In other words, these authors propose that if interpretations contradict existing research literature, such interpretations are important to state as a possible contribution to new knowledge production. As such, what made autoethnography a powerful choice was the ability to either elaborate and critique or extend knowledge in relation to existing research (Adams et al., 2015). This was particularly valuable to me because, through this research, I could determine whether my “theory supports, elaborates, and/or contradicts personal experience … [and whether it] provides a foundation on which to elaborate or provide a counter narrative to the meanings and implications” (Adams et al., 2015, p. 94) involved.

The three students in my autoethnographic stories achieved varying degrees of success, and while success is not a fixed bar that everyone must reach, it remains a fluid and ever-changing goal. Research suggests that students with higher levels of grit tend to exhibit qualities such as ferocious determination, conscientiousness, self-control, sustained effort, and a strong ability to persevere when challenges arise (Duckworth et al., 2007; Duckworth & Quinn, 2009; Muenks et al., 2017). Although my students Caleb and Violet initially displayed few, if any, of these qualities, over time, both began to exhibit several of these traits. Grit appeared to change daily for these students, depending on the ongoing circumstances each student faced.

Personality also played an important role in influencing grit. When Caleb and Violet first began physics class, both exhibited many fixed-minded traits. They showed signs of poor coping mechanisms, frequently blaming themselves or others, and appeared neither resilient nor adaptable when physics questions were slightly altered from their practice questions or when new topics were built on from previous concepts. Adhira, on the other hand, demonstrated many growth-minded traits, including taking responsibility for successes and failures, a willingness to accept challenges, and the ability to turn areas of weaknesses into areas for growth.

Grit is found to be closely associated with conscientiousness, more so than the other Big Five factors (Duckworth et al., 2007; Poropat, 2009; West et al., 2015), which reflects Adhira’s experiences. From the outset, Adhira had the appearance of several conscientiousness traits, as described by Caspi et al. (2005) and Poropat (2009), including being self-motivated to learn, highly inquisitive, and actively taking control of her learning by seeking further enrichment for future growth. Her success was consistent throughout Grades 11 and 12, although her familial difficulties did impact her conscientiousness.

Given that conscientiousness is significantly tied to grit, literature from Noftle and Robins (2007) and Poropat (2009) also indicate that agreeableness and low neuroticism are contributing factors. This aligns with what Caleb and Violet demonstrated in class. I observed that both students were notably vulnerable to anxiety and stress. However, with my interventions and support, both appeared to be coping much better; their stress seemed significantly reduced, and they began to display traits associated with conscientiousness. While the success of all three students might suggest a connection to extraversion, I observed that Violet was successful despite being strongly introverted.

At the beginning of the Grade 11 Physics course, I noticed that both Caleb and Violet exhibited a low grit, poor academic performance, and a fixed mindset. I initially thought these attributes would negatively impact their long-term academic success. To address their fixed mindsets, I decided it was important to examine what motivated Caleb and Violet. For Caleb, his journey in Physics seemed particularly challenging. He appeared to be motivated by extrinsic rewards, which encouraged growth, though often temporarily. In contrast, both Adhira and Violet were not extrinsically motivated like Caleb.

I needed to offer frequent positive and meaningful reinforcement to encourage and motivate both Caleb and Violet’s self-worth. Through these supportive verbal affirmations, I aimed to strengthen Caleb’s and Violet’s sense of self-worth, and through this process, I observed that their stress level decreased, they became less agitated, and they showed signs of educational satisfaction. Over time, as evidenced by their gradual but steady growth, they were motivated to take on small yet challenging goals.

Ryan and Deci (2000) note that feelings of self-worth are linked to internal regulation, since such feelings are connected to extrinsic motivation through an external locus of control. Cultural influences are another external locus of control that need to be recognized. Although Adhira was pleased to receive positive reinforcement, I believe the primary motivation driving her to success was her Indian culture. When Adhira and I spoke about the commonalities between our cultures, Adhira shared that failure was not an option and, therefore, there was always this continuous pressure to succeed through effort and hard work. My experiences with Adhira in relation to this research suggests that as researchers deepen their understanding of human differences, diversity, and equity, these perspectives become essential for investigating students' grit and achievement. As it can be for many learners, success looked to be addictive for Caleb, Adhira, and Violet. As these three students experienced higher levels of academic success, they began to act with a sense of independence and autonomy, which gave me the indication that it reinforced their internal locus of control and, therefore, promoted a high degree of intrinsic motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Caleb began to develop many intrinsically motivated traits when schools shifted to an online learning approach due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Caleb controlled his environment. He did not have to worry about others watching him; he could regulate his own pace and progress, and no longer needed to be micromanaged. Through such independent actions, he achieved significant academic success.

Like Caleb, Violet began to experience even more substantial growth and success as she adopted more independent actions, initiatives, and proactive strategies toward completing minor assessments, such as probes, and major assessments, such as quizzes and tests. Through these efforts, she not only improved in areas where she previously had deficiencies, such as gaps in content understanding, but she also became one of the highest-achieving students in Grade 12 Physics.

The greatest strides in all three students’ successes stemmed from their independent actions and autonomy. I noticed that for Caleb and Violet, extrinsic motivators became less important, with intrinsic motivators eventually taking over as a primary driving force for their significant transformations. Although Adhira continued to face challenging familial issues, she moved toward success through her own intrinsically motivated choices (e.g., willingness to extend her abilities, seeking out enrichment opportunities, or leaning on peers for assistance). From my perspective as her teacher, this represented a major shift for Adhira. Her efforts to manage both her academic responsibilities and her parents’ health circumstances demonstrated to me a high degree of grit in both her academic and personal realms.

As Caleb, Adhira, and Violet developed progressively stronger intrinsically motivated traits, they displayed a high level of grit as defined by Von Culin et al. (2014). It is worth noting that, without the extrinsic motivators to initially stimulate and drive Caleb’s and Violet’s successes, they may have struggled to succeed in Physics. Finally, before moving into the structural ideology section, I wish to remind readers that these autoethnographic stories are presented from my perspective as a Physics teacher. It is possible that others with different positionalities might draw alternative conclusions.

In this section, I will connect my analysis to structural ideology; that is, the implications of social, income, and familial structures.

It is a reality that some students enter school with a certain set of privileges when compared to others. Consequently, it can be suggested that social, income, and familial structures are ongoing elements that impact grit and student success for these three students and many others. Prior to this research, as a teacher, I was involved in many school-led strategies and interventions to address student failure and learning deficits. In relation to the deficit ideology discussed by Gorski (2016, 2018), I noticed that although addressing learning deficits helped some students, I do not recall it significantly improving my students’ academic skills overall. In fact, for some students who showed brief improvement, others quickly reverted to their original routines. Given my experience doing this research, I now believe it is vital to consider the negative implications that structural deficits such as poverty, familial structures, race, ethnicity, culture, and social status have on students. By addressing deficit ideology solely by promoting grit through changes in personality, work habits, and effort, structural deficits are likely to be, consciously or unconsciously, overlooked.

In my experience with these three students, social structures played varying roles, depending on the individual. Although Violet was socially isolated and did not have other peers to rely on for help, it did not appear to have a major impact on her success. Even at her highest point of academic success, Violet socialized very little. For Caleb and Adhira, however, their contexts were significantly different. One of the significant elements that negatively impacted Caleb’s grit and academic success was his difficulty in forming meaningful and strong relationships with other students in the physics class. Hannover et al. (2013) describe one barrier to academic success as negative peer interactions. While some social bonds already existed among students, Caleb did not seem to have connections to many of them.

Adhira’s situation was different, as she was culturally straddling between two cultures. This likely impacted Adhira’s grit and success in physics. Due to Adhira’s ability to adapt and move between her insider and outsider cultural identities, she was able to form meaningful connections and minimize negative peer interactions.

While Carter (2008) uses cultural straddling in the context of racial and ethnic heritage, I believe this concept can also apply to Caleb. Caleb appeared to struggle significantly with adapting and balancing between the culture of his social group and that of the physics classroom. In class, it seemed Caleb aimed to maintain an appearance of toughness and avoid showing vulnerabilities, even at the cost of his academic success. Perhaps, within his social group, being perceived as smart was at odds with the image of being ‘cool,’ and excelling in school might have diminished his social standing. It is important to recognize that while the COVID-19 pandemic necessitated Caleb’s shift to online schooling, it effectively removed the issue of cultural straddling. Once Caleb participated in online schooling, I noticed major strides in his grit and academic success. I believe this progress had occurred largely because Caleb could avoid social pressures and keep his academic achievements private from his peer group.

Family income is also known to have substantial impacts on individual student’s success, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic (Alvarez-Rivero et al., 2023). Caleb was an only child, living in a single-parent household. I believe he experienced significant economic disadvantages, as demonstrated by how he came to school each day with limited learning resources. While many students had the latest technological gadgets, Caleb used a broken but still functional, older-generation iPhone. He lacked access to a laptop, which created challenges for enhancing his at-home learning. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted significant economic disparities among my students. Those with abundant economic resources (e.g., access to the Internet and a computer) maintained or even improved their academic performance, whereas students with little to no resources suffered. This aligns with the findings of Alvarez-Rivero et al (2023). For Caleb, if he had not had access to the public Internet or his iPhone, he would likely have failed. This contrasts with students like Adhira and Violet, who came to school every day with the necessary resources needed for success. Therefore, students with privileges, such as adequate resources, have a higher likelihood of experiencing sustained success.

Family dynamics also play a critical role in grit and student success. In examining Violet’s story, parental expectations may have played a key role in her sense of self-worth, possibly impacting Violet’s high levels of agitation, stress, and frustration. It seemed that Violet derived part of her self-worth from what the important people in her life thought of her. While Violet’s mother wanted Violet to excel, the constant pressures, high expectations, and perceived parental disappointment appeared to weigh heavily on Violet. Although it was not just one factor that led to Violet’s overwhelming success, I believe part of her academic progress was connected to her mother’s changing ideas about what it means to be successful. It might be reasonable to suggest that when Violet’s mother’s mindset shifted, parental pressure and demands may have lessened. As a result, Violet exhibited a much happier, stress-reduced attitude, possibly because she no longer had to worry about what her mother thought of her.

For much of her time in Grades 11 and 12, Adhira maintained a high degree of academic success. However, the moment her parents became ill and needed Adhira as a translator, everything abruptly changed. I observed that Adhira’s greatest barrier to her grit and academic success was the difficulty she experienced balancing both her scholarly commitments and obligations to her sick parents. In many instances, she had to assume an adult role in her family while simultaneously trying to complete her academic studies. It was likely she was overwhelmed and worried due to the responsibilities placed upon her. As a result, she frequently missed class or arrived late. Adhira’s story demonstrates that uncontrollable elements, such as family dynamics and parental obligations, can have negative impacts on students’ academics, grit, and chances of high-level success. In my view, if Adhira’s parents had not depended so heavily on her, I strongly believe she would have maintained her upward trajectory of growth and academic success.

Through stories like those of Adhira and Violet, it is reasonable to claim that familial dynamics played a contributory role in their grit and success. From my observations, I believe Caleb lived in a family where economic barriers existed. I experienced many failed attempts to collaborate with Caleb’s mother in supporting him, even though I believe that her inability to do so was for legitimate reasons. In my experience as a high school teacher, I have never met a parent who did not care about their child’s education. While Violet’s and Caleb’s parents offered different levels of support, I noticed how significant parental guidance and involvement can be in steering students onto a pathway to success.

Discussion

In a world of different educational ideologies, educators, policymakers, and researchers exist across different ideological spectrums. For Gorski (2016, 2018), deficit and structural ideologies exist on two ends of a wide spectrum and should not be treated as binary concepts. In education, educators who believe in deficit ideology believe that people can change their success and situations through the recognition and alteration of attitudes, behaviours, and mindsets. On the other end of the spectrum, educators who identify with structural ideology believe that disparity in education is due to structural barriers and the inequitable distribution of access and opportunities (Gorski, 2016, 2018). As Gorski noted, grit aligns more closely with deficit ideology.

Throughout this research, the three learners within these stories appeared to have their grit change daily depending on the ongoing circumstances that each student faced. Consequently, deficit ideological elements such as personality, mindset, and motivation played important roles. For example, in my view, the personality traits from the Big Five factors which gave the impression of significantly influencing grit were conscientiousness, agreeableness, and what Rimfeld et al. (2016) identify as neuroticism.

Another important attribute influencing my students’ grit was whether they had indications of fixed or growth mindset traits. From my viewpoint, when some of my students leaned into a fixed mindset, they gave the indication that they were not as adaptable to different circumstances and, consequently, displayed poor coping mechanisms. As Dweck et al. (1995) illustrated, such individuals with fix mindsets tend to have less grit because they often fault themselves for not being born more capable of achieving success. Through my support and interventions, my students eventually responded and slowly embraced a growth-minded attitude. This adoption of a growth mindset was essential because, as these authors have identified, such individuals would likely blame their negative outcome on a lack of study commitment and effort.

In investigating motivation and its relationship to grit in my classroom, I noticed that different motivators had varying levels of impact. While I offered small prizes as extrinsic rewards, they were often short-lived. What had the most impact on my students was addressing and reinforcing their sense of self-worth. To do this, I frequently provided positive and meaningful reinforcement, not only to sustain achievement but also to minimize their vulnerability to frustration, stress, and agitation. Eventually, through such sustained efforts, I began to see my students take even more responsibility through independence and autonomy. As a result, my students required fewer extrinsic motivators because they indicated to me that their apparent success was what drove them to succeed at even harder goals, thereby reinforcing their grittiness.

It should be noted that while cultural influences may be perceived as a structural ideological factor, for one student (Adhira), cultural influences also acted as a relevant external locus of control. Therefore, it appears that, as we deepen our understanding of human differences, diversity, and equity, these perspectives need to be considered.

Depending on the student, social structures seemed to play differing roles. In one case (Caleb), a student’s inability to form meaningful and strong relationships with other peers may have negatively contributed to their academic success. However, in the case of another student (Violet), success did not hinge on making social connections because, at this student’s highest point of academic success, they did not socialize with many individuals. This highlights the issue of students potentially culturally straddling between dominant and non-dominant cultures. As was the case for one student in my autoethnographic story (Adhira), ethnic students who are not from the dominant culture may need to negotiate between dominant and non-dominant customs, attitudes, and practices to be successful in school. Outside of ethnicity, it could be the difficulty associated with straddling the cultural codes between social groups that conflict with the culture of scholarly success.

In any society, students arrive at school from different types of households. Students who arrive with limited financial means may experience this limitation as a detrimental impact on success and learning, as evidenced by one of the students in my autoethnographic story (Caleb). This was particularly evident during the COVID-19 pandemic when the shift to online learning occurred. For students with the financial means to access the Internet and technology, they continued with online learning. However, those with limited access likely struggled to participate in schooling. As investigated by Alvarez-Rivero et al. (2023), this disparity was evident for children from different socio-economic classes throughout the United States and Canada.

Within different households, diverse family dynamics play a critical role in grit and student success. While well-intentioned, some parents may be too invested, which may consequently contribute to a child’s anxiety, agitation, and stress. This was the impression I had with one of my students in this research (Violet) because, as the constant pressures continued, I believed it negatively impacted their sense of self-worth. However, in supporting parents and redefining their supportive roles, such actions likely facilitated a better pathway to reinforcing a child’s sense of self-worth, grit, and ultimate success. It is important to consider that, for some students, parents may not be involved for a multitude of legitimate reasons. Educators must not resort to deficit ideological thinking (i.e., parents do not care about their child’s education). In my experience, I have not encountered even one parent who does not care about their child’s education. This thinking applies to two of the students in this story. One student lived in a single-parent household (Caleb), while another student’s parents did not speak English and always required a translator (Adhira). As both stories reveal, there are structural implications at play.

Culturally, in Western society, there is a narrative which focuses on the individual and, as a result, the issue of meritocracy prevails. Subsequently, it could be said that meritocracy is embedded into society’s mindset (Gorski, 2016, 2018; Ladson-Billings, 2006, 2021; Williams et al., 2020). What initially came across as a way to address inequities in society (e.g., an individual’s failings) has now become a justification for such. Therefore, the perception is that if individuals put in tremendous efforts, they could, through these efforts, end up being successful at addressing inequity. Sadly, such a meritocratic view also extends into the student context, as the view holds that if students can demonstrate hard work and considerable effort, they could also achieve positive future outcomes (Carter, 2008). While this may be true for some students, for others, it may not be the case.

An idolization of meritocracy can be damaging and dismissive of the very real issues students face. While I do not suggest that educators abandon addressing effort and hard work, there are concrete justifications as to why educators also need to take structural elements into account. As illustrated by my autoethnographic reflections in this paper, structural considerations have an influential role to play. As a practicing teacher, when supporting struggling students, I now take both deficit and structural elements into consideration; I use such knowledge to facilitate a pathway to support my learners, providing them with the greatest chance to improve their grit and achieve a high degree of success.

This research was limited to three learners. As a qualitative methodology, the purpose of this autoethnographic research was not to generalize findings to the entirety of a population. However, this medium was a space for me to elaborate on, critique, and extend knowledge from existing research (Adams et al., 2015) concerning my experience as a Physics teacher. Interpretations within this research were filtered through both the literature review and my own positionality. As Mason-Bish (2019) affirms, this positionality ultimately influences how I view, interpret, and construct the realities within my classroom, as well as how I interact with my learners. Researchers with different positionalities may have arrived at different conclusions. That said, because autoethnography is a qualitative methodology, qualitative approaches embrace the multiplicity of plausible truths within the universe (Denzin & Lincoln, 2011).

My experiences teaching Caleb, Adhira, and Violet suggest that changes are needed in K-12 education. Given the number of students who do not graduate high school, have lower-than-expected grades, or are disengaged in today’s classrooms, attention must be given to addressing the disconnect between students and schools, with the aim of improving students’ sense of self-worth, developing their personality profiles, and building on gritty traits. For too long, I have struggled with the widening achievement gap related to student success within my physics classroom. I have tried to find ways to progressively change my teaching practice through reviewing current educational research. However, few topics ever piqued my interest until the research on grit came along. Prior to doing this research, I held the belief that if learners could embrace grit, they would eventually have the capacity to experience success. However, as this research brings to light, when addressing student achievement, it is vital not to dismiss the elements related to structural ideology. Because students exist within unequal power structures (e.g., social, income, and familial), these structural elements also need to be addressed to promote conditions of academic success.

Ultimately, in a world where there is an uneven playing field, it would be short-sighted to focus purely on grit ideology as a way of fostering academic success. Since grit ideology is dominated by deficit ideology (Gorski, 2016, 2018), this approach would be a disservice to the students coming into our schools. As a result, students grappling with different life circumstances will require a teacher’s awareness and consideration of such structural barriers. Once acknowledged, grit may then be used to help educators facilitate and improve upon their pupils’ success and goals.

Adams, T. E., & Ellis, C. (2012). Trekking through autoethnography. In S. D. Lapan, M. T. Quartaroli, & F. J. Riemer (Eds.), Qualitative research: An introduction to methods and designs (pp. 189-212). Jossey-Bass.

Adams, T. E., Ellis, C., & Jones, S. H. (2017). Autoethnography. In J. Matthes, C. S. Davis, & R. F. Potter (Eds.), The international encyclopedia of communication research methods (pp. 1-10). John Wiley & Sons.

Adams, T. E., Jones, S. H., & Ellis, C. (2015). Autoethnography: Understanding and research. Oxford University Press.

Akos, P., & Kretchmar, J. (2017). Investigating grit at a non-cognitive predictor of college success. Review of Higher Education, 40(2), 163-186. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2017.0000

Alvarez-Rivero, A., Odgers, C., & Ansari, D. (2023). Elementary school teachers’ perspectives about learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. npj Science of Learning, 8(1), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-023-00191-w

Apple, M. (2010). Global crises, social justice, and education. Routledge.

Berger, R. (2015). Now I see it, now I don’t: Researcher’s position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 15(2), 219-234. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794112468475

Bolen, D. M. (2014). After dinners, in the garage, out of doors, and climbing on rocks: Writing aesthetic moments of father-son. In J. Wyatt & T. E. Adams (Eds.), On (writing) families: Autoethnographies of presence and absence, love and loss (pp. 141-147). Brill.

Cain, S. (2013). Quiet: The power of introverts in a world that can’t stop talking. Crown.

Carter, D. (2008). Achievement as resistance: The development of a critical race achievement ideology among black achievers. Harvard Educational Review, 78(3), 466-497. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.78.3.83138829847hw844

Caspi, A., Roberts, B., & Shiner, R. (2005). Personality development: Stability and change. Annual Review of Psychology, 56(1), 453-484. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141913

Cummins, J. (2021). Rethinking the education of multilingual learners: A critical analysis of theoretical concepts. Multilingual Matters.

Datu, J. A. D. (2021). Beyond passion and perseverance: Review and future research initiatives on the science of grit. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.545526

Denzin, N. K. (2014). Interpretive autoethnography (2nd ed.). Sage.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2011). The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (4th ed.). Sage.

Duckworth, A. (2016). Grit: The power of passion and perseverance. Collins.

Duckworth,

A. L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M. D., & Kelly, D. R. (2007).

Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal

of Personality and Social Psychology,

92(6),

1087-

1101. http://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1087

Duckworth, A. L., & Quinn, P. D. (2009). Development and validation of the short grit scale (grit-s). Journal of Personality Assessment, 91(2), 166-174. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890802634290

Dumfart,

B., & Neubauer, A. C. (2016). Conscientiousness is the most

powerful noncognitive predictor of school achievement in adolescents.

Journal

of Individual Differences,

37(1),

8-15.

http://doi.org/10.1027/1614-0001/a000182

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Ballantine Books.

Dweck, C. S., Chiu, C., & Hong Y. (1995). Implicit theories and their role in judgments and reactions: A world from two perspectives. Psychological Inquiry, 6(4), 267-285. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli0604_1

Ellis, C., Adams, T. E., & Bochner, A. P. (2011). Autoethnography: An overview. Historical Social Research, 36(4), 273-290. https://doi.org/10.12759/hsr.36.2011.4.273-290

Eskreis-Winkler, L., Shulman, E. P., Beal, S. A., & Duckworth, A. L. (2014). The grit effect: Predicting retention in the military, the workplace, school and marriage. Frontiers in Psychology, 5(36), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00036

Frank, L., & Fisher, L. (2020). 2019 report card on child and family poverty in Nova Scotia: Three decades lost. Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, Nova Scotia. https://www.policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/Nova%20Scotia%20Office/2020/01/2019%20report%20card%20on%20child%20and%20family%20poverty.pdf

Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures selected essays. Basic Books.

Gore, J. S., Thomas, J., Jones, S., Mahoney, L., Dukes, K., & Treadway, J. (2016). Social factors that predict fear of academic success. Educational Review, 68(2), 155-170. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2015.1060585

Gorski, P. C. (2016). Poverty and the ideological imperative: A call to unhook from deficit and grit ideology and to strive for structural ideology in teacher education. Journal of Education for Teaching, 42(4), 378-386. http://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2016.1215546

Gorski, P. C. (2018). Poverty ideologies and the possibility of equitable education: How deficit, grit, and structural views enable or inhibit just policy and practice for economically marginalized students. In R. Ahlquist, P. C. Gorski, & T. Montaño (Eds.), Assault on kids and teachers: Countering privatization, deficit ideologies and standardization in U.S. schools (pp. 99-120). Peter Lang.

Hamilton, M. L., Smith, L., & Worthington, K. (2008). Fitting the methodology with the research: An exploration of narrative, self-study and auto-ethnography. Studying Teacher Education, 4(1), 17-28. https://doi.org/10.1080/17425960801976321

Hannover, B., Morf, C. C., Neuhaus, J., Rau, M., Wolfgramm, C., & Zander-Music, L. (2013). How immigrant adolescents’ self-views in school and family context relate to academic success in Germany. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43(1), 175-189. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2012.00991.x

Hill, P. L., Burrow, A. L., & Bronk, K. C. (2016). Persevering with positivity and purpose: An examination of purpose commitment and positive affect as predictors of grit. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(1), 257-269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9593-5

Hochanadel, A., & Finamore, D. (2015). Fixed and growth mindset in education and how grit helps students persist in the face of adversity. Journal of International Education Research, 11(1), 47-50. https://doi.org/10.19030/jier.v11i1.9099

Ivcevic, Z., & Brackett, M. (2014). Predicting school success: Comparing conscientiousness, grit and emotion regulation ability. Journal of Research in Personality, 52, 29-36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2014.06.005

Kohn, A. (2014). Grit? A skeptical look at the latest educational fad. Independent School, 74(1), 104-108. https://www.alfiekohn.org/article/grit/

Ladson‐Billings,

G. (2006). It's not the culture of poverty, it's the poverty of

culture: The problem with teacher education. Anthropology

& Education Quarterly,

37(2),

104-109.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1525/aeq.2006.37.2.104

Ladson-Billings, G. (2021). Culturally relevant pedagogy: Asking a different question. Teachers College Press.

Mason-Bish, H. (2019). The elite delusion: Reflexivity, identity and positionality in qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 19(3), 263-276. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1468794118770078

McIntosh, P. (2005). White privilege: Unpacking the invisible knapsack. In M. B. Zinn, P. Hondagneu-Sotelo, & M. A. Messner (Eds.), Gender through the prism of difference (3rd ed.) (pp. 278–281). Oxford University Press.

Merriam, S. B. (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. Jossey-Bass.

Merriam, S. B., Johnson-Bailey, J., Lee, M., Kee, Y., Ntseane, G., & Muhamad, M. (2001). Power and positionality: Negotiating insider/outsider status within and across cultures. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 20(5), 405-416. http://doi.org/10.1080/02601370120490

Muenks, K., Wigfield, A., Yang, J. S., & O'Neal, C. R. (2017). How true is grit? Assessing its relations to high school and college students' personality characteristics, self-regulation, engagement, and achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 109(5), 599-620. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/edu0000153

Noftle, E. E., & Robins, R. W. (2007). Personality predictors of academic outcomes: Big five correlates of GPA and SAT scores. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(1), 116-130. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.1.116

Poropat, A. E. (2009). A meta-analysis of the five-factor model of personality and academic performance. Psychological Bulletin, 135(2), 322-338. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0014996

Radl, J., Salazar, L., &

Cebolla-Boado, H. (2017). Does

living in a fatherless household compromise educational success? A

comparative study of cognitive and non-cognitive skills. European

Journal of Population,

33,

217-242.

http://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-017-9414-8

Riemer, F. J. (2012). Ethnographic research. In S. D. Lapan, M. T. Quartaroli, & F. J. Riemer (Eds.), Qualitative research: An introduction to methods and designs (pp. 163-188). Jossey-Bass.

Rimfeld,

K., Kovas, Y., Dale, P. S., & Plomin, R. (2016). True

grit and genetics: Predicting academic achievement from personality.

Journal

of Personality and Social Psychology,

111(5),

780-789. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000089

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 54-67. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1020

Savin-Baden, M., & Major, C. H. (2013). Qualitative research: The essential guide to theory and practice. Routledge.

Steinmayr, R., Weidinger, A. F., & Wigfield, A. (2018). Does students’ grit predict their school achievement above and beyond their personality, motivation, and engagement? Contemporary Educational Psychology, 53, 106-122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2018.02.004

Von Culin, K. R., Tsukayama, E., & Duckworth A. L. (2014). Unpacking grit: Motivational correlates of perseverance and passion or long-term goals. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 9(4), 306-312. http://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.898320

Walford, G. (2021). What is worthwhile auto-ethnography? Research in the age of the selfie. Ethnography and Education, 16(1), 31-43. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457823.2020.1716263

West, M. R., Kraft, M. A., Finn, A. S., Martin, R. E., Duckworth, A. L., Gabrieli, C. F., & Gabrieli, J. D. (2015). Promise and paradox: Measuring students’ non-cognitive skills and the impact of schooling. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 38(1), 1-23. http://doi.org/10.3102/0162373715597298

Williams, K. L., Coles, J. A., & Reynolds, P. (2020). (Re) creating the script: A framework of agency, accountability, and resisting deficit depictions of black students in P-20 education. Journal of Negro Education, 89(3), 249-266.