What’s With All This Race Talk Anyway? A Literature Review on Antiracist Education

Ashlee Sandiford

University of Regina

Author’s Note

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Ashlee Sandiford at ashleesandiford@outlook.com

Abstract

This article reviews the developing literature on antiracist education and the emerging frameworks for recognizing racism in educational spaces. Much of the literature draws on critical race theory as the underlying framework to conceptualize race and racism. Many scholars emphasize the need for antiracist practices in K-12 education. There was, however, significant research evidence that suggested a gap between antiracist pedagogy and knowledge and the actual implementation into everyday teaching practices. The review also found evidence of suggested strategies teacher education and school division professional development programs should engage with to help aid the implementation of antiracist education in schools and classrooms— evidently, the review points to the importance of faculty (educators, support staff, administrators, superintendents and school division employees involved in policy development) to reflect on their experiences with race. I conclude with an invitation to recognize and understand how to show up as an antiracist educator, today, tomorrow and for the future.

Keywords: race, racism, antiracist education, critical race theory, racialized students

What’s With All This Race Talk Anyway? A Literature Review on Antiracist Education

Racialized students and educators are victims of a system that exacerbates institutional racism (Boykin, et al., 2020). Whiteness is engendered and reinforced in many facets of education, such as, but not limited to, interpersonal relationships, curriculum, pedagogical approaches and policies (Arneback & Jamte, 2022; Boykin, et al., 2020; Hambacher & Ginn, 2021; Sleeter, 2017). The socially constructed ideas of race and racism are both psychologically and physiologically harmful and stressful for racialized students and teachers (Boykin, et al., 2020). In this literature review, race refers to the classification of individuals based on physical characteristics such as skin colour and hair texture which have helped shape systems of privilege and oppression. Race was created as a result of white supremacist ideologies, birthing the term Whiteness which I refer to in this paper as the invisible normative standard where individuals perceived as white benefit from unearned privileges and power dynamics between racialized groups (Hambacher & Ginn, 2021). I also theorize Whiteness similarly to Bonilla-Silva’s (2023) definition, “Whiteness emerged as the imperative of categorizing the ‘us’ to conquer or control the colonial ‘them’…” (p. 194). From this lens, racism is defined as a systemic injustice that disadvantages racialized groups and individuals based on their race or perceived racial identity. Another perspective of racism comes from Moreton-Robinson's (2015) concept that racism is the child of colonialism and therefore is connected to the theft and appropriation of Indigenous lands in Canada (Bonilla-Silva, 2023). This definition is imperative to understanding the depths of racism towards Indigenous students in Canadian schools and the effects of anti-Indigenous hate. Furthermore, the term racialized refers to individuals or groups who do not benefit from Whiteness, rather, this term is coined out of the comparison of whiteness. Bonilla-Silva (2023) theorizes racialization as “race-making” where we “racialize as we enforce racial order, and we enforce racial order as we racialize. The nuances of race, racism, Whiteness and racialization contribute to the analysis of what it means to be antiracist.

Discussions involving race and racism have increased over the past few years, bringing awareness of antiracist education to the forefront of learning institutions. For example, Berchini (2017) calls on antiracist faculty to “enact pedagogies that connect knowledge of personal privilege with understandings of [W]hiteness in relation to institutional power” (Hambacher & Ginn, 2021, p. 332). I conceptualize antiracism with the help of Berchini (2017), while also considering antiracism as the intentional opposition to racism through the promotion of racial equity that works to disrupt and dismantle systems of oppression derived from race and racism. Situated in a Canadian context, in this literature review, antiracism includes racial equity for Black, Indigenous, people of colour, newcomer students and all other racialized groups.

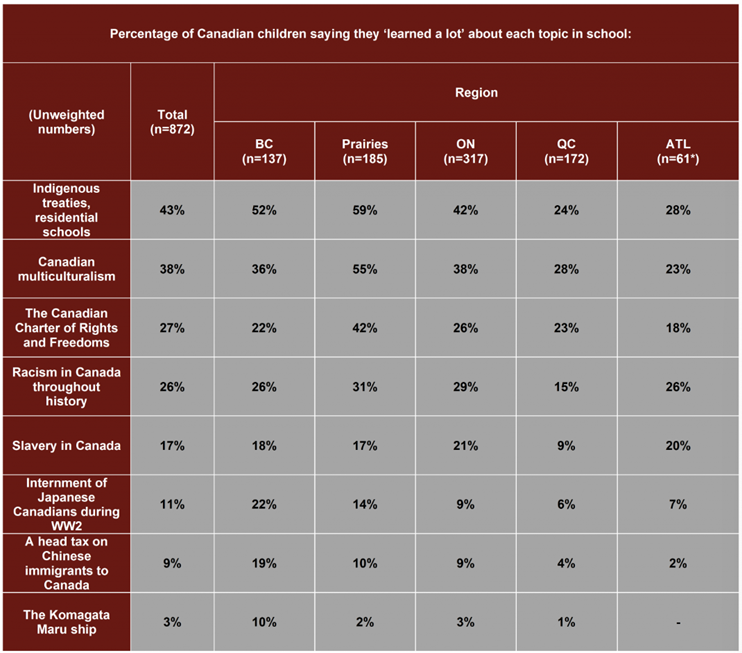

The University of British Columbia in conjunction with the Angus Reid Institute conducted a study involving 872 Canadian youth aged 12 -17. According to the study, over half (54%) of students declared that “kids name call or use insults based on racial or ethnic background at their school, while smaller proportions say kids are made to feel unwelcome (38%) or are bullied (42%) based on their racial or ethnic background” (Angus Reid Institute, 2021). The study also revealed the depth of teaching about racism across Canada and what students say they did, or did not learn, about Canada’s history with racism. This research (see Figure 1) demonstrates some of the ways that racism is prevalent in Canadian schools. Therefore, a review of the literature is necessary to understand how to combat unsafe and unhealthy learning environments faced by racialized students.

Figure 1

Percentage of Canadian children saying they ‘learned a lot’ about each topic in school (retrieved from Angus Reid Institute, 2021).

I conducted this literature review as a result of being witness to racism in Saskatchewan schools. As a practicing teacher who embeds antiracist approaches into the classroom, I observe first-hand, the benefits, questions and critical analyses from students about the world around them. However, I could not help but notice the overall hesitation from educators when it comes to ‘knowing what to do when racism occurs’ and ‘how to disrupt Whiteness and structures of power (places of oppression) within schools. Even after a few mandatory antiracist professional development sessions, I continued to question the confidence of educators to feel equipped to teach and respond to students in antiracist ways. With a large focus on mental health and post-COVID-19 recovery, I find it paramount to investigate the ways racism shows up in education.

Implementing and fostering anti-oppressive practices within schools positively affects the mental health and well-being of racialized students and teacher educators. Stanley (2022) suggests, “to unmake racisms in the first place, we not only need to undo inherited racist practices, we also need to find and build connections that cross over racist exclusions and dismantle the systems of power that divide us” (p. 141). To do so, I argue that two questions must be asked:

· Where does racism show up in education and how do teacher educators identify various forms of racism?

· What strategies and best practices are recommended for implementing antiracist education in educational systems, classrooms and curriculum development?

Teachers dedicated to providing social justice practices recognize the need for combative solutions to racism in education (Hambacher & Ginn, 2021). Incorporating antiracist education allows teachers to make a positive difference in the lives of racialized students and their colleagues (Kumashiro, 2000). That being said, disrupting oppressive learning spaces becomes challenging due to the reliance on teachers’ beliefs, practices and values upheld by educational systems such as school divisions and faculties of education. Within the overall field of education, there needs to be significant changes to professional development, curriculum and pedagogy to adopt anti-oppressive policies and practices.

Positioning Myself in This Work

To situate myself within the realm of antiracist education, I (Ashlee) am biracial (Black and white) and am confronted with the nuances of navigating and deconstructing racism in both my personal and professional life. Given firsthand encounters with racial discrimination, I find myself aware of racial disparities happening in the classroom and question the capacity with which faculty feel equipped to respond. My reluctancy stems from research by Kishimoto (2018) who argues, “…in order to effectively incorporate anti-racist pedagogy into courses, awareness and, more importantly, self-reflection regarding the faculty’s positionality has to begin before going into the classroom and that these issues need to be continuously revisited alongside the teaching” (p. 543). Based on this positionality, at what point are faculty expected and willing to critically self-reflect?

Further, I wonder about the possibilities of working in an education system that no longer contributes to experiences of racism but works to dismantle and disrupt Whiteness—the ways that white people benefit from unearned privileges (Hambacher & Ginn, 2021). Within these educational spaces, ranging from bathrooms and lockers to desks and playgrounds, to conversations with white students and colleagues, both hidden and nuanced as well as overt and unambiguous acts of racism manifest themselves. My lived experiences represent a unique dichotomy that includes the realities of both racism and privilege. Being biracial has provided meaningful insights to understand and relate to the perspectives of many. However, my reality should not be misconstrued with the challenges being biracial presents. I navigate my experiences with an invitation to explore, question and challenge race and racism. This is the exact reason for the writing of this literature review—to invite practitioners to question, challenge and sit with the uncomfortability of race and racism as it pertains to educational settings.

Methodology

To conceptualize the positionality of racism and how it transpires in educational spaces, I conducted a literature review which extended to theorizing and compiling strategies and best practices to implement antiracist pedagogy in schools and classrooms. The University of Regina’s library database was the primary search engine used. Additionally, Google Scholar and Theses Canada searches were performed. Keyword searches included ‘antiracism,’ ‘antiracist,’ ‘antiracist education,’ and ‘antiracist pedagogy.’ I also utilized the ‘snowball effect’ method to gather additional literature cited in previously searched and found literature. I mainly focused on literature situated in Canadian and US contexts, however, literature from New Zealand is also referenced. No specific parameters on the timeframe of the literature were followed but attention was given to more recent literature.

Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework underlying this literature review is firmly grounded in the principles of critical race theory (CRT). CRT serves as the guiding lens through which the dynamics of racism are comprehended and analyzed (Ladson-Billings & Tate, 1995; Solorzano & Huber, 2020). This conceptual framework enables educators to gain a profound understanding of the multifaceted nature of racism and its various forms within educational contexts. By employing CRT, educators can effectively understand the contexts in which racism is rooted, thereby enhancing their ability to identify, address, and dismantle systemic racial inequalities within educational spaces. Ladson-Billings and Tate (1995) affirm CRT as an “…intellectual and social tool for deconstruction, reconstruction, and construction: deconstruction of oppressive structures and discourses, reconstruction of human agency, and construction of equitable and socially just relations of power” (p. 9).

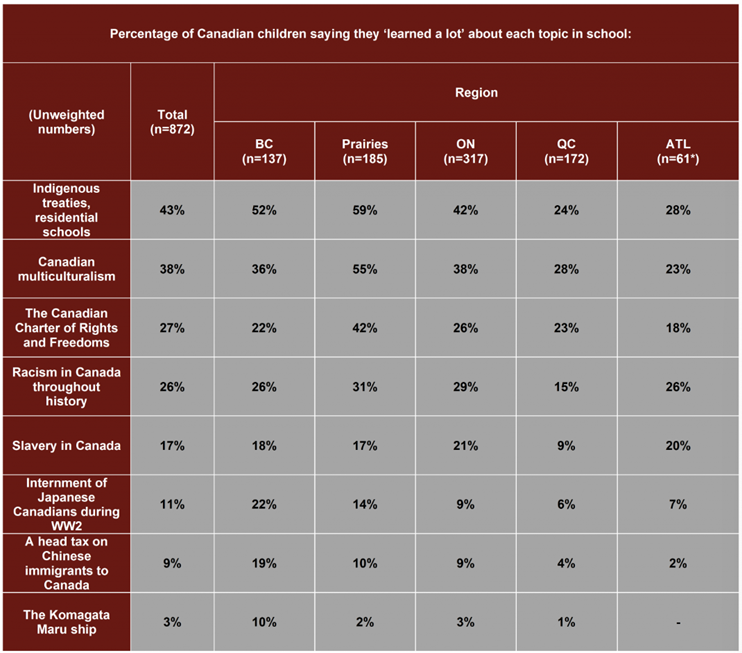

Within the framework of CRT, multiple tenets exist (Bell, 1987; Ladson-Billings & Tate, 1995; Solorzano & Huber, 2015, 2020; Solorzano, 1998). For this literature review, I address four specific tenets (see Figure 2): (1) the permanence of racism; (2) the value of experiential knowledge and counter-storytelling; (3) the concept of interest convergence; (4) and critiques of liberalism (Sleeter, 2017). These foundational tenets, interwoven within the fabric of this review, serve to strengthen educators' comprehension of the acts of racism within educational settings. Moreover, these tenets offer insights into proactive strategies that educators can employ to dismantle racial inequities and foster an environment conducive to antiracist practices within schools.

Figure 2

Tenets of Critical Race Theory (retrieved from Bedford & Shaffer, 2023, p. 7).

Note: Adapted from Bell (1980, 1991), DeCuir and Dixson (2004), Delgado and Stefancic (2017), Sleeter (2017), and Solorzano and Yosso (2001, 2002). First published in (Shaffer et al., in press).

Critical Race Theory to Understand Racism in Schools

The Permanence of Racism

Central to critical race theory (CRT) is the fundamental principle that racism possesses an enduring presence. CRT posits that race and racism are socially constructed concepts influenced by political forces (Lopez & Jean-Marie, 2021) and reinforced by institutional structures. Gillborn (2015) expands on this notion, asserting that critical race theorists argue the majority of racism remains hidden beneath a veneer of normalcy, with only the most overt and blatant forms being acknowledged as problematic by the general public. However, Bonilla-Silva (1997, 2023) contends that the permanence of racism is perpetuated through a circular pattern rooted in the belief that racist behaviour establishes racism, which in turn validates the existence of racism. This circularity arises from a failure to ground racism in social relations among different racialized groups. Neglecting to acknowledge racism as a socially constructed phenomenon only serves to exacerbate its continuing nature. Ladson-Billings and Tate (1995) propose that if racism were truly isolated and manifested solely through random acts of violence, society would witness educational excellence and equity within public school environments. However, they argue that African American students often experience success outside of the public school system, indicating the continued vitality of racism within educational spaces. In other words, structural and systemic racism in which the education system is grounded in prevails. Therefore, the entirety of the education system must be challenged and reworked from an anti-racist viewpoint. Other relevant research points out that anti-Indigenous racism such as Residential Schools, Indian Hospitals, the “60s Scoop” and the overwhelming population of Indigenous children in child and family services play a significant role in education, specifically the effects of racism towards Indigenous student's school experiences (Efimoff and Sarzyk, 2023). In essence, Partridge (2014) suggests that society incorrectly assumes that white individuals incidentally or coincidentally hold the majority of power and privilege within society. However, CRT compels us to explore alternative perspectives that challenge white supremacist ideologies, which devalue and dehumanize racialized communities, thus, creating a comprehensive understanding of the prevailing social order that rejects such arguments and promotes an inclusive and equitable society.

Experiential Knowledge and Counter-Storytelling

A second principle central to critical race theory proclaims the significance of listening to the experiences and stories of racialized groups. Because of their omnipresence and normalization in schools, racist experiences tend to go unacknowledged (Hambacher & Ginn, 2021). Therefore, stories of racialized groups become seemingly important. Counternarratives give racialized people an opportunity to name their own reality which consequently illuminates sociopolitical complexities in education (Vesley et al., 2023). Solorzano and Yosso (2002) assert that experiential knowledge intentionally calls majoritarian stories into question. Majoritarian stories purposefully discount racism to “maintain dominant group status over People of Colour” (Solorzano & Huber, 2020, p. 22). Solorzano and Huber (2020) go on to suggest, that “majoritarian stories (re)construct and justify systems of subordination that lead to inequitable social arrangements and, consequently, disparate outcomes of Community of Colour in nearly every sphere of social life, including education, health, wealth, and politics” (p. 9). The power of story creates connections between individuals which become a necessity for comprehending, identifying and disrupting racism within educational spaces. A portion of this literature review is aimed at amplifying the voices of racialized individuals and their experiences within school settings.

Interest Convergence

As articulated by Bell (1987), interest convergence refers to the prevailing notion that white individuals advocate for the interests of people of colour only when such interests align with and promote their own interests. White individuals experience fragility regarding the possibility of their status and power eroding, despite the fact that the actual pursuit is that of racial equity (Sleeter, 2017). Therefore, to ameliorate the effects of racism, educators must actively dismantle and interrogate white supremacist ideologies. Moreover, it becomes crucial to delve deeper into the examination of privilege, encouraging teachers and community members to reflect upon how their perceptions of school may be influenced by underlying interest convergence dynamics. Undeniably, interest convergence plays a pervasive role in perpetuating white supremacist ideologies within educational environments, necessitating the implementation of a CRT perspective to identify acts of racism. Interest convergence shows up throughout this literature review by addressing the necessary reflections faculty must commit toward antiracist education.

Critiques of Liberalism

The final tenet to be considered here is the critique of liberalism and the inadvertent dynamics of neutrality, colour blindness, and meritocracy that continue to shape and maintain the dominant group. Neutrality and colour-blindness discount any and all experiences of racism while at the same time mask white privilege and power (Sleeter, 2017). CRT scholars explain meritocracy to be the belief that success in society is solely dependent on the hard work and determination of individuals—neglecting to consider the influences and results of power dynamics (Solorzano & Huber, 2020). Microaggressions are presented through this review as a way to draw attention to nuanced identify racism in addition to showcasing how liberalism upholds the ideas of neutrality and colour blindness. CRT’s critique of liberalism challenges deficit thinking models as they often justify poor academic success through group membership, “…typically, the combination of racial minority status and economic disadvantagement” (Valencia, 2010, p. 18). In other words, Valencia (2010) conceptualizes deficit thinking as a framework that blames “students’ poor schooling performance [on] their alleged cognitive and motivational deficits” (p. 18), rather than questioning institutional and personal biases and the ways these injustices have historically influenced student learning. Such a lens, liberalism overlooks the consequences of deficit thinking by situating racism and Whiteness as “not our problem” and continues to preserve the status quo. Valencia and Solorzano (1997) speak against liberalism as it ignores structural barriers and, rather than eradicating racism, liberalism focuses on assimilating people, families, and communities into a society grounded in Whiteness. In other words, “the formula for action becomes extraordinarily simple: change the victim” (Ryan, 1971, p. 8). Therefore, a neutral discourse can become an oppressive technique to withhold optimal learning opportunities for school success for such students.

Bedford and Shaffer (2023) draw attention to the necessity of CRT in educational spaces, “employing key tenets established by critical race theorists can confront systems of injustice and provide tools for teachers, preservice teachers, and you to engage in change” (p. 5). By conceptualizing racism through the following four central tenets, the permanence of racism, experiential knowledge and counter-storytelling, interest convergence and critique of liberalism educators can talk about and understand race and racism in tangible ways. CRT should extend beyond this literature review as a grounding foundation for educators to generate thoughtful conversations and critical learning opportunities.

Considering Intersectionality in Relation to CRT

A considerable amount of literature pointed to the idea that antiracist frameworks present intersectional systems of oppression such as class, gender, and sexual orientation (Annamma & Winn, 2019; Kishimoto, 2022; Luft, 2010; Mutitu, 2010; Partridge, 2014), suggesting that these systems of oppressions are ‘mutually sustaining’ (Partridge, 2014) and that dismantling one enables/requires the dismantling of all. Scholars Russel Bishop et. al., (2003) conducted several studies to investigate how educators could provide a better learning space for Maori students. Bishop (n.d, 0:10).), conceptualizes intersectionality and the benefit of antiracist education for all students:

…[W]hat’s good for Māori is good for everybody,’ … [and] ‘What’s good for everybody is not necessarily good for Māori.’ … [R]eally what our data is showing really, really, really, really clearly which is just great news for us is that as Māori students improve their achievement in our schools so do non-Māori as well. But what we’re really delighted about in the latest evidence that we’re gathering as well, is that after five- or six-years teachers get more and more effective. And as they get more and more effective Māori student’s achievement is improving. What’s really quite wonderful on the latest data we’ve got is in fact that Māori are now achieving at the same levels as non-Māori students in our schools.

In offering a critique of intersectionality, Kishimoto (2022) argues that intersectionality can sometimes be used to avoid discussions of race by intentionally focusing on other forms of oppression. Luft (2010) emphasizes the importance of intersectionality, while at the same time arguing that “…intersectionality is not the most strategic methodological principle for the early stages of microinterventions [classrooms, workplaces and workshops] when the objective includes antiracist consciousness change”. (p. 103). In other words, intersectionality is complex and “a crucial premise when seeking broad interventions”, but when initiating early stages of microinterventions, one must begin with racism (Luft, 2010, p. 102). Focusing on race must be “centrally” and “singularly” discussed to reintroduce it to the conscious discourse (Luft, 2010, p. 103). Because I am taking my direction from Luft, the scope of this literature review focuses on the singularity of race and the ways racism manifests in school learning environments.

Conceptualizing Antiracism in Education

Microaggressions in the Classroom

Racism in school learning spaces significantly impacts racialized students and teachers. However, overt and obvious forms of racism do not exceed all variants of racism. In other words, racist acts can be directed at immigration status, language, and culture which are affiliated to race (Kohli, 2009). CRT scholars refer to these subtle racially charged actions as microaggressions (Hantke, 2022; Kohli & Solorzano, 2012). Scholar Derald Wing Sue (2010) identifies microaggressions in three forms: race, gender and sexual orientation. Sue (2010) defines the act of microaggressions as “the brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioural, and environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative racial, gender, sexual orientation, and religious slights and insults to the target person or group” (p. 5). Although all of the encompassing forms of microaggressions are important to note, I highlight ‘racial microaggressions’, a term coined by Chester Pierce in the 1970s. Pierce defines racial microaggressions as, “…the everyday subtle and often automatic ‘put-downs’ and insults directed toward Black [People of Colour and Indigenous] Americans (Pierce et al., 1977; Sue, 2010).

Microaggressions within education can be the cause of inequalities which directly impacts the success of marginalized groups (Murray, 2020). The harm caused by microaggressions towards racialized groups cannot be underestimated. Pierce (1974) builds on the impact of microaggressions and states:

These [racial] assaults to black dignity and black hope are incessant and cumulative. Any single one may be gross. In fact, the major vehicle for racism in this country is offenses done to Blacks by Whites in this sort of gratuitous never-ending way. These offenses are microaggressions. Almost all black–white racial interactions are characterized by white put-downs, done in automatic, preconscious, or unconscious fashion. These mini disasters accumulate. It is the sum total of multiple microaggressions by whites to blacks that has pervasive effect to the stability and peace of this world. (p. 515)

This explanation of microaggressions conceptualizes the dangers not exclusive to Black students and teachers, but for all racialized groups. Therefore, overlooking microaggressions can lead to students feeling invalidated, devalued and under-respected, particularly as a result of belonging to a certain group (Murray, 2020; Sue, 2010). The damage caused by microaggressions on racial groups in learning spaces consequently hinders students from “underperform[ing] despite having the ability to succeed” (Murray, 2020, p. 184). Even further, racialized students subject to experiencing trauma in their lives are significantly impacted by microaggressions (Woods-Jaeger et al., 2021). A clinical study by Woods-Jaeger et al. (2021) examined the correlation between childhood trauma and resilience and whether microaggressions furthered a person’s ability to demonstrate resilience. They found that racial microaggressions negatively impacted the resilience of African-American adolescents who previously experienced trauma (Woods-Jaeger et al., 2021).

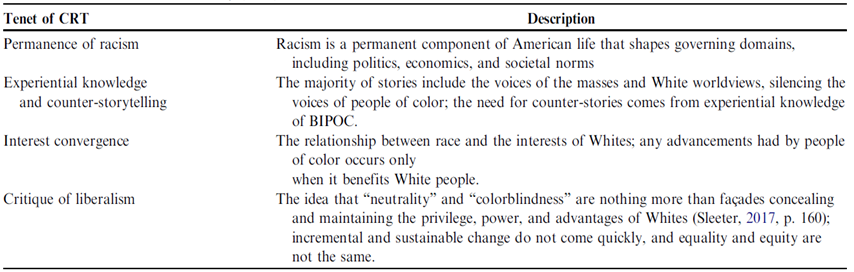

In order to identify and respond to racial microaggressions, Kohli and Solorzano (2012) amplify the importance of understanding different types of microaggressions, the context in which they occur, and the effects microaggressions present (see Figure 3). By engaging in this process, educators will find themselves better equipped to respond to racial microaggressions as they arise.

Figure 3

A model for understanding microaggressions (from Kohli & Solorzano, 2012, p. 447).

There are layers to understanding racial microaggressions and where they manifest in education. It becomes paramount then to have a rich and comprehensive grasp of where, how, and when, microaggressions occur. As defined earlier, microaggressions are discrete, unconscious acts of violence toward racialized groups (Hantke, 2022; Kohli & Solorzano, 2012; Pierce, 1974; Sue, 2010). Perez and Solorzano (2014) remind educators:

They are: (1) verbal and non-verbal assaults directed toward People of Color, often carried out in subtle, automatic or unconscious forms; (2) layered assaults, based on race and its intersections with gender, class, sexuality, language, immigration status, phenotype, accent, or surname; and (3) cumulative assaults that take a psychological, physiological, and academic toll on People of Color. (p. 302)

With the context of microaggressions in mind, several types and examples of microaggressions are laid out by Murray (2020) from Lynch (2019) and Sue (2010). Identifying microaggressions can be challenging, therefore the following quotes offer examples from Murray (2020):

1) Prejudging academic ability:

· Setting low expectations for students from certain groups or backgrounds.

· Believing that a student’s dialect or language skills are problematic.

· Stating how a nonwhite student is articulate or well-spoken.

2) Devaluing culture, heritage, and religious traditions:

· Scheduling assignments, projects, and examinations on cultural or religious holidays

· Disregarding religious traditions

· Expressing Eurocentric and ethnocentric views

3) Criminalizing behaviour:

· Referring to undocumented students as illegals

· Making assumptions about students and their backgrounds

· Banning certain ethnic clothing, head coverings, such as hats or hoodies, or hairstyles

4) Disregarding income inequality:

· Assigning class projects that disregard socioeconomic status and penalize students with fewer financial resources

· Assuming all students have access to and are proficient with the use of computers, technology, and applications for communications related to academic assignments

· Excluding students from accessing certain activities due to the expense of the activity

5) Making politically charged statements:

· Expressing racially charged political opinions in class

· Using inappropriate political and partisan humour in class that degrades members from other groups

· Hosting debates in class that place students holding opposing views in bad predicaments

6) Dismissing difference:

· Conveying only heteronormative examples in class

· Calling on, engaging, and validating one gender, class, or race of students while ignoring other students during class

· Requiring students with nonvisible disabilities to identify themselves in class. (pp. 184 – 185)

Being able to name various racial microaggressions is helpful in critically recognizing them in schools. Additionally, these examples of microaggressions within a school context are seemingly complex, Kohli and Solórzano (2012) studied the importance of knowing and properly pronouncing someone else’s name. Within the study, Nitin, a South Asian man, shared an example from middle school.

Rather than learning a name outside his cultural comfort zone, a teacher decided to change this young student’s name to his own. He explained: When I was in the seventh grade, I missed my first day of class. One of my teachers was calling roll and couldn’t pronounce my name – Nitin. As a joke, he crossed my name out of the gradebook and told the class he was renaming me ‘[Frank]’…. after himself. Everyone thought it was pretty funny and the next day at school, everyone kept calling me ‘[Frank].’ I soon grew used to the name and within a few months, I was introducing myself as ‘[Frank].’ I went to that school for six years - seventh through twelfth grade. By the time I graduated, I firmly thought of myself as ‘[Frank],’ so much so that at college, I introduced myself as ‘[Frank]’ to everyone, including other South Asians. (Kohli & Solórzano, 2012, p. 451)

Name-changing derives from a long history of slavery and colonization (Fryer & Levitt, 2004). However, the teacher in Nitin’s situation, unknowing of this history, caused harm and stripped a piece of Nitin’s cultural identity away (Kohli & Solorzano, 2012). Kay (2018) articulates this experience as passing – a term he defines as “members of a minority cultural group/race might ‘pass’ when, for whatever reason, they can present themselves as majority” (p. 184). This includes but is not limited to name-changing on resumes, self-identifying as the majority race, and disowning aspects of one’s marginalized identity to pass in society (Fryer & Levitt, 2004; Kay, 2018; Kohli & Solorzano, 2012).

Based on personal school experiences as a student and now educator, I can attest to the negative impacts microaggressions have on identity and the capability to feel confident in one’s skin. Therefore, I find it significant to suggest additional microaggressions often experienced in schools:

· Getting asked “where are you from” and then being called into question because the response does not line up with the answer the questioner was hoping for. This question is often followed up by “but, where are you really from?”;

· Othering (Kumashiro, 2000) racialized people by assuming their culture, country, and nationality based on race;

· Using literature as a means to justify slur-terminology;

· Using the same consequence or reaction for non-racialized incidents in racist situations;

· Tokenism as a form of microaggression. For example, asking racialized students or teachers to speak or provide their opinion on behalf of their racialized group. This behaviour assumes all racialized groups have the same experiences and results in individual invisibility; also known as assimilation (Hasberry, 2013) or role entrapment (Hasberry, 2013).

Evidently, microaggressions are often the result of good intentions with negative impacts. They can be challenging specifically for white educators to identify as they often are subtle and inadvertent (Sue, 2010). It is important that educators can confidently identify microaggressions to disrupt racism in schools. Showing consideration for racialized groups means the recognition of microaggressions should not be the responsibility of racialized groups. Faculty (educators, administrators, and school districts) must become aware of the choice of words and behaviours used while promoting a climate of empathy and cultural humility (Murray, 2020). Failure to challenge microaggressions can lead to negative school experiences for racialized students (Woods-Jaeger et al., 2021). Therefore, the need for antiracist education and practices is imperative for a more equitable education.

Analyzing Everyday Racism in Schools

Antiracist education utilizes critical thinking skills to deconstruct power relations (Mark, 2003) by acknowledging an unequal distribution of knowledge and resources based on the social construct of race (Dei & Vickers, 1997). Noteworthy comments from Boykin et al. (2020) include:

· Black people are experiencing exhaustion and other physiological effects resulting from racism;

· Racism extends far beyond police brutality and into most societal structures;

· Despite being the targets of racism, Black people are often blamed for their oppression and retaliated against for their response to it;

· Everyone must improve their awareness and knowledge (through both formal education and individual motivation) to fight racism;

· Anti-racist policies and accountability are key to enact structural reformation. (p. 776)

These quotes point to the significance and necessity for antiracism practices. Additionally, Arneback and Jamte (2022) point out that racist acts manifest in schools in, “prejudice, microaggressions, discrimination, exclusionary practices, ethnocentric education, hate speech and racial violence” (p. 192). Therefore, implementing antiracist actions provides environments where everyone can learn, see themselves as learners and feel confident to be themselves. Efimoff and Sarzyk (2023) investigated the impacts of historical education and systemic racism specifically involving anti-Indigenous racism and found promising impressions on how students thought, felt and behaved towards Indigenous students. In this case, antiracist education helped to build empathy within a community to understand the lasting effects of racism. Antiracist education benefits everyone.

A consistent theme showed up throughout the research that emphasizes the need for antiracist education as it relates to the psychological well-being of racialized students and educators (Boykin et al., 2020; Vesley et al., 2023; Sleeter, 2017). The lack of equity in learning spaces results in negative experiences for racialized students that lead to disengagement from learning. For racialized students and educators to feel confident in learning environments, attention to antiracist practices is crucial. Walker and Wellington (2022) critique that changing how we teach and research is not sufficient but rather “recognizing and overturning racist complicity in classrooms and academic departments […] means reckoning the colour-evasiveness that pervades the constructions of education” (p. 31). To say you are an antiracist but lack any sort of initiative to deconstruct racist acts only perpetuates the problem further. Those who benefit from white supremacy are required to make sacrifices in order to bring about sufficient change (Lopez & Jean-Marie, 2021). Unfortunately, colour blindness and meritocracy challenge the existence of racism and prevent sacrifices to dismantle white supremacy.

What’s With All This Race Talk Anyway?

“Why can’t we just leave race out of it?” “I don’t see colour, I see a person”. “Racism doesn’t exist anymore; leave it in the past!” Consistent with CRT, colour blindness, meritocracy, and the emphasis on the permanence of race, demonstrate why we cannot just leave race out of it. Solomon et al. (2005) suggest, “[w]hite people, who overwhelmingly take up positions of power, remain committed to the myth of a meritocratic system (p. 68, as cited in Partridge, 2014). The phrases stated above are a few examples that maintain the deficit discourse that belittles racialized people and justifies white supremacy in schools. Confronting white supremacy in schools requires the dismantling and reconstruction of the colonial status quo which often is challenged or overlooked by white people, as the knowledge, histories and theories benefit them (Partridge, 2014). As such, the embodiment of white supremacy lives through the refusal to acknowledge the way Whiteness shows up in schools—pointing to neutrality and colour-evasiveness. In a comparable manner, Leonardo (2004) states,

It is not only the case that whites are taught to normalize their dominant position in society; they are susceptible to the forms of teachings because they benefit from them. It is not a process that is somehow done to them, as if they were duped, are victims of manipulation, or lacked certain learning opportunities. Rather, the colour-blind discourse is one that they fully endorse (p. 144).

Although ignoring the way racism manifests in schools seems like an endearing “out”, ignorance of racism is inexcusable and must be recognized to disrupt systemic racism to move towards antiracist education (Vesley et al., 2023). Perspective shifting is challenging because often as humans, we only view the world through our own experiences which explains why “to whites…many of whom think of race as something that comes up only occasionally in specific situations… is a very hard reality to appreciate” (Brookfield, 2017, p. 208). Vesley et al. (2023) help us understand that those who benefit from systems of power find it challenging to recognize white supremacist privilege and often respond defensively towards racialized groups only further perpetuating deficit discourse and structural inequity. Schumacher-Martinez and Proctor (2020) attribute these feelings to Critical Whiteness Studies that suggest, “nice white people are complicit in maintaining systemic oppression through the superficial need to be seen as good and not part of the problem, instead of an openness to engage in critical self-audit awareness” (p. 251). Undergirding the necessity of this work, Hambacher and Ginn's (2021) exploration of race-visible education revealed the benefits of disruptive self-reflection to help repair injustices experienced by racialized groups. Such that, Williams et al. (2020) promote the necessity for educators to be well-equipped in responsive teaching so that “…practitioners [can] foster inclusive classrooms, facilitate difficult dialogues, and support all voices in the classroom” (p. 370). Undoubtedly, the literature calls on faculty and teacher-education programs to embrace and enact antiracist frameworks and pedagogy.

Challenges and Resistance Towards Antiracist Education

Hambacher and Ginn’s (2021) comprehensive review of the past decades’ race-visible education proved the tenets of CRT, mentioned earlier, permeate resistance from educators. Ill-equipped teacher education programs prevent the production of antiracist education in schools (Andrews et al., 2021, Browne et al., 2023; Sleeter, 2017,). Excluding antiracist pedagogy inhibits the ability to create just environments of learning for everyone which provides opportunities for “the reproduction of whiteness in structures [continues] to oppress raced, gendered, and classed individuals and communities who deviate from the norms established by the ideology of whiteness” (Calderon, 2006, p. 73). Therefore, the absence of antiracist education presents dangerous consequences for racialized students. Boykin et al. (2020) explain how individuals who are faced with racism experience heightened levels of psychological and physiological stress which require constant emotional regulation strategies. Donaldson (1997) echoes such experiences and proclaims, “Students become angry, withdrawn, less confident, depressed, guilty, and many times hostile toward their educational experiences” (p. 31) when incidents of racial violence frequently occur at school. It is clear a focus on teacher education programs and professional development for experienced teachers becomes essential to dismantling and addressing racism in schools. First, attention to personal values and beliefs must be addressed as Hambacher and Ginn (2021) have observed skeptical, discouraging and at times aggressive resistance from educators.

Personal Values and Implicit Bias

The dilemma of enacting antiracist education can be that educators may find antiracist pedagogy contradicts their own personal values and beliefs (Hickling‐Hudson & Ahlquist, 2003). This is referred to as implicit bias—unconscious and automatic associations and interpretations—which has a tremendous impact on learning environments (Staats, 2016). Decision-making, disciplinary actions and treatment of racialized students are tremendously affected by implicit bias (Staats, 2016). A study on discipline disparities proved that K-12 students of colour were sent to the principal’s office more regularly, and experienced disciplinary measures that were more subjective in nature, such as disrespect, behaviour issues or excessive noise, versus their white counterparts who were disciplined for objective infractions such as smoking and vandalism (Skiba et al., 2002). Disproportionate discipline can lead to adverse effects as Annamma and Winn (2019) emphasize, “pervasive deficit mindsets reinforce and (re)produce societal inequities” (p. 318). Mutitu (2010), explains how teachers will often predetermine and nurture students they perceive should be successful which results in a deficit mindset for the rest of the students. In addition, Scheff (2000), recognizes these nurtured students are usually “talented, middle class or closest in action and appearance to middle class” (p. 91). Therefore, faculty need opportunities to unpack their own implicit bias before implementing an antiracist framework (Hambacher & Ginn, 2021). It is important to note, self-reflections on race and racism do not solely pertain to white faculty, but also to racialized faculty and their experiences with racism. Mutitu (2010) highlights the necessity for educators of colour to reflect on their personal experiences with race, “students will not learn to address issues of racial inequity if the teacher hasn’t come to terms with [their] own experiences of race, because the teacher isn’t a neutral participant in this process” (p. 44). Additionally, Partridge (2014), explores the significance for white educators to address the role they play in sustaining white supremacy within schools. She asserts, “When white bodies come to understand themselves as agents of white supremacy, unwilling agents perhaps but agents nonetheless, we are better able to address how our bodies continue to function in this manner and see the ways we can contribute to anti-racism and anti-colonial agendas” (Partridge, 2014, p. 74).

Although research points to a commitment to self-reflection, emotionality is a major factor that must be considered when attempting to create change and disrupt social norms. Zembylas (2010) identifies, “[w]hen teachers resist reform efforts, it is often because it threatens their self-image, their sense of identity, and their emotional bonds with students and colleagues by overloading the curriculum and intensifying teachers’ work and control from the outside” (p. 222). This type of hesitation can be conceptualized as white fragility, a term coined by Robin Diangelo (2011) in her article White Fragility. In the context of education, Jayakumar and Adamian (2017) point to white fragility manifesting in university programs:

White college students are often protected from confronting their own racial biases and assumptions … primarily due to the centering of [W]hiteness in curricula and instruction, the predominance of whites on higher education campuses, and the absence of challenges to white students’ dispositions in regard to race and racism. (p. 916)

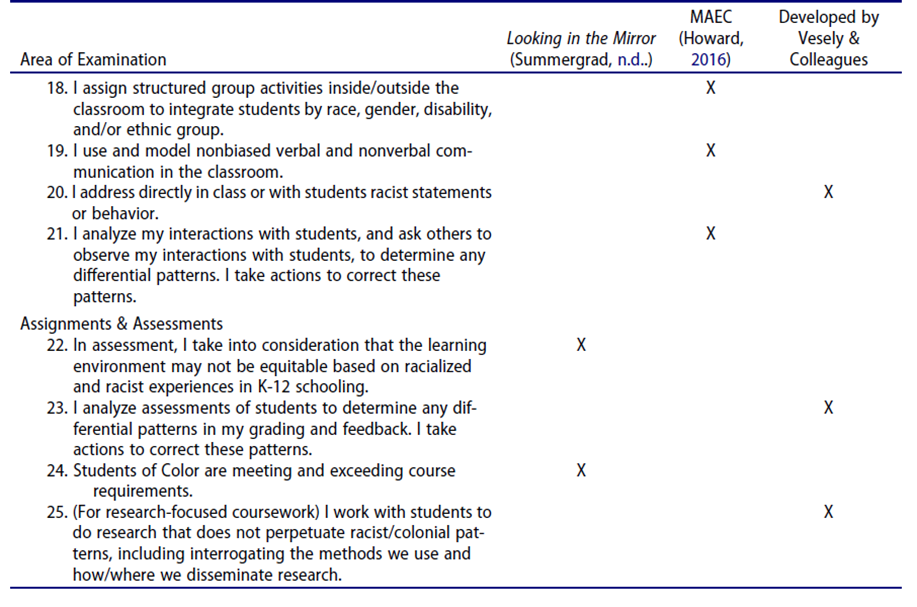

Participating in self-reflection is a critical tool for implementing an antiracist framework. Faison and McArthur (2020) identify the necessity for “critical reflection and deliberate action” (as cited in Vesley et al., 2023, p. 5) in order for transformative practices to surface in schools. Vesley et al. (2023) describe these actions to be “…de-centering the most privileged voices, surfacing racist structures, and teacher[s] looking inward and outward to actively promote antiracism” (p. 6). To guide educators to critically reflect and engage in transformational work, Vesley et al. (2023) created an Antiracist Pedagogy Course Audit tool, see Figure 4. Adapted from Summergrad (n.d) and Howard (2016), Vesley et al.’s (2023) audit tool draws on CRT tenets similar to the ones that informed this literature review. Additionally, their audit tool is grounded in Friere’s (2013) conceptualization of critical consciousness, specifically paying attention to the influence and outcomes of power and the results of societal inequities. Lastly, the audit tool reminds us (learners) that “antiracist action is not possible without ongoing interrogation of self and one’s positionality” (Vesley et al., 2023, p. 6).

Figure 4

Antiracist Pedagogy Audit Tool (from Vesley et al., 2023, p. 7-8).

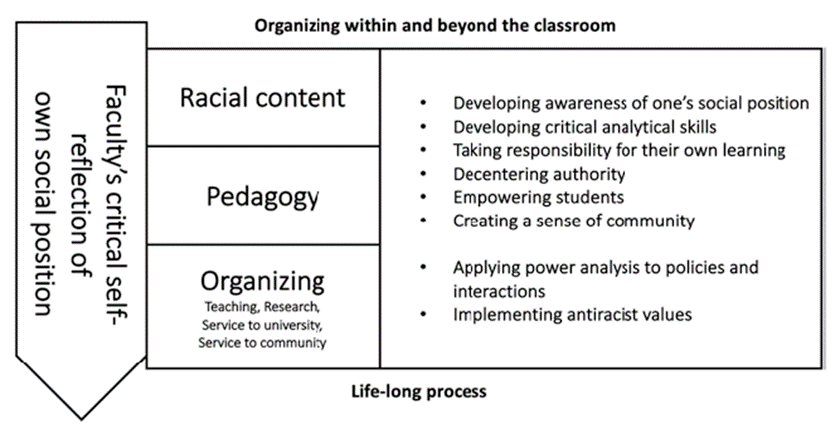

In addition to Vesley et al.’s (2023) audit tool, Kishimoto (2022) created a framework (see Figure 5) that helps faculty address their social position within education. By becoming aware of one’s social positionality and power within society and the classroom, the learning environment can be positively impacted (Kishimoto, 2018, 2022). Kishimoto (2022) summarizes the three components of antiracist pedagogy as:

1) Incorporating topics of race and inequality into course content

2) Teaching from an antiracist approach, for example, through decentering authority and creating community in the classroom

3) Antiracist organizing within the campus are linking efforts to the surrounding community (p. 116)

The proposed frameworks are starting points for self-reflection, the reduction of racial biases and the transition for teaching towards an antiracism approach.

Figure 5

Antiracist pedagogy as an organizing project (from Kishimoto, 2022, p. 117).

Teacher Education Programs

Although the curriculum offers a foundation for what to teach, antiracist education offers a framework for how to teach. Kishimoto (2022) asserts that “antiracist pedagogy not only raises students’ awareness of their social positions in society but also requires faculty to become aware of their social position and think about their roles and responsibilities in a racialized society” (p. 115). Because of the interpretation freedom educators have with the curriculum, the choice of teaching through an antiracist lens then becomes optional. Also referred to as the social and political influences (interest convergence) that continue to uphold systems of power and influence (Kishimoto, 2022). In more recent cases, teacher-education programs are implementing antiracist pedagogy and theories in university courses (McGregor, 2020, as cited in Kishimoto, 2022). Ladson-Billings (1995) argues that “teacher education programs throughout the nation have coupled their efforts at reform with revised programs committed to social justice and equity (p. 466). More recent events such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the killing of George Floyd and an influx of race-visible literature hitting the shelves “pushed race, antiracism, and systemic racism into mainstream discussions” (Kishimoto, 2022, p. 105). In turn, this shifts the focus in education for prospective teachers to “…support equitable and just educational experiences for all students” (Ladson–Billing, 1995, p. 466).

A report carried out in Saskatchewan (Barreno, 2016) focused on analyzing a 1988 study that examined the Saskatchewan curriculum for implementation of Global Education—a term related to antiracist education. In this 2016 report, Barreno concluded the need for pre-service teacher programs to include Global Education theories (p. 7). Education Social Studies (ESST) 317: Teaching Engaged Citizenship: Social Studies and Social Environmental Activism is a course now offered by the University of Regina’s Faculty of Education program, evidently, a by-product of the current academic push towards teaching for social justice (Barreno, 2016). Marilyn Cochran-Smith (1991, as cited in Browne et al., 2023) vocalizes the need for pre-service teachers to see themselves engaged in systems of power and privilege and to understand how to make decisions critically based on these findings. To conceptualize the need for teacher education programs, Nieto (2000), outlines the pervasiveness of antiracist education. She asserts,

A concern for social justice means looking critically at why and how our schools are unjust for some students. It means analyzing school policies and practices—the curriculum, textbooks and materials, instructional strategies, tracking, recruitment and hiring of staff, and parent involvement strategies—that devalue the identities of some students while overvaluing others. (p. 183)

Additionally, Sleeter (2017) recognizes that post-secondary institutions are structuring the orientation of programs toward social justice and culturally responsive teaching, however, she also identifies “the great majority continue to turn out roughly 80% [w]hite cohorts of teachers even though [w]hite students are less than half of the K-12 population” (p. 155). Although these statistics represent the context in the US, many Canadian scholars point to similar findings (Hampton, 2016; Partridge, 2014; Robinson, 2005). Therefore, the initiation of providing antiracist education in teacher education programs will increase awareness and at the very least help towards the development of antiracist action within schools.

Professional Development for Educators: Accountability

In her article, Kishimoto (2022) addresses the uncertainty of the longevity of antiracism education as these mainstream discussions can be a temporary trend. Therefore, professional development for practicing teachers and administrators becomes essential (Sleeter, 2017; Hambacher & Ginn, 2021). Mutitu (2010) further asserts the need for professional development, “More often than not, teachers will hold negative and lowered expectations for lower class and minority students than middle to upper-class white students” (p. 45). Consequently, this type of expectation disparity focuses more on the emotional toll on white students rather than on students [and teachers] of colour (Sleeter, 2017), also recognized in CRT as interest convergence.

Providing teachers with additional professional development and mandating antiracist education through pedagogical practices, curriculum and antiracist policy changes are approaches to combat the avoidance of antiracist education. Love (2019) argues, “At the end of the day, white teachers need to want to address how they contribute to structural racism. They need to join the fight for education justice, racial justice, housing justice, immigration justice, food justice, queer and trans justice, labour justice, and, above all, the fight for humanity” (para. 12). However, conversations and professional development centred around antiracist education cannot solely rely on staff meetings or book clubs; professional development must be continuous (Boulden & Borden, 2022). Implementing professional development that involves the sharing of personal stories and narratives typically sways others to act (King, 2023). From a CRT perspective, counterstories give space for racialized individuals to share their experiences and provide a voice to help reform education (Sleeter, 2017). In psychology, this strategy is known as the identifiable victim approach which is used to increase empathy toward a personal situation (King, 2023). This is also known as “pedagogies of strategic empathy—“personal experiences evoke[ing] an emotional response which, in turn, can increase a desire to enact change” (King, 2023, p. 32). In addition to personal narratives and strategic empathy, Boulden and Borden (2022) suggest, [i]ncorporating teachers, for example, as co-presenters can help ensure that the professional development clearly speaks to teachers’ interests and is digestible to individuals who may not be as far along in their journey toward being anti-racist educators” (p. 319). While the literature pointed to themes of increased awareness through self-reflection, teacher education programs and professional development for antiracist education, the sections that follow offer an invitational approach to continue beyond this review for engaging in antiracism work.

Looking Forward: An Invitation to Engage

Overall, this literature review highlights the need for antiracist education. Although a call for antiracist education has been sought after in research, scholars point out the absence of practical frameworks and suggestions for what antiracist actions look like in educational environments (Arneback & Jamte, 2022). For action to come to fruition, antiracist practices must be embedded in ongoing practice. To dissect all the ways antiracist education can show up in schools is out of the scope of this literature review. However, moving towards an antiracist approach, I invite you, educator, to continue on the journey of self-reflection and enlightenment to the ways racism shows up in education. The following frameworks found within the review are presented as an invitation to how you can show up as an antiracist educator, today, tomorrow and for the future.

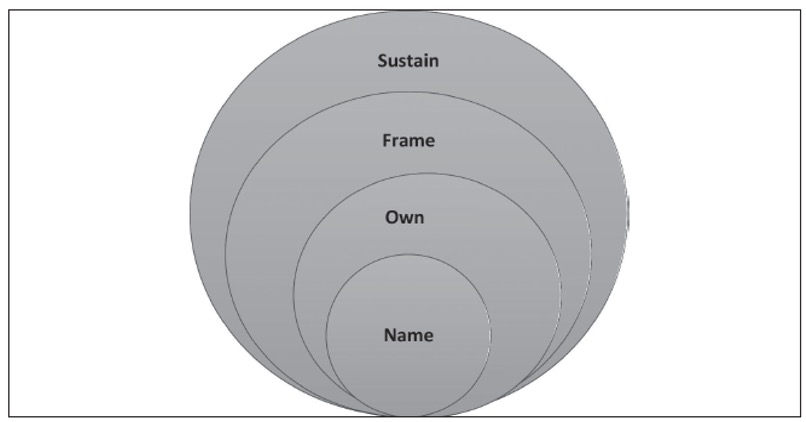

Name, Own, Frame and Sustain (NOFS) Framework

Drawn from the lived experiences and stories of Black and white school leaders, Lopez and Jean-Marie (2021) developed a framework (Figure 6) to address specifically anti-Black racism in schools. However, the concept of intersectionality can be used to adapt the following framework for marginalized experiences such as anti-Indigenous racism, anti-immigrant racism, and gender and sexually diverse groups.

Figure 6

Framework for Action – Name, Own, Frame, and Sustain (NOFS) (from Lopez & Jean-Marie, 2021, p. 58).

Naming is the understanding and categorizing of racist occurrences in everyday school practices. Through this process, educators must question their positionality, self-reflect, and examine what they need to learn and unlearn. Antiracist action cannot come solely from racialized educators as this responsibility heightens the pain, trauma, and suffering of racialized educators (Lopez & Jean-Marie, 2021). The ability to identify microaggressions would be an example of naming.

Second, owning that there is a racism problem is fundamental to antiracist action. When faculty take ownership of racial issues, it allows them to: 1) see how they and others are complicit; and 2) reflect on possible and necessary actions. By owning, educators recognize racism within schools and take responsibility to act. Critical Race Theory would suggest owning is conceptualized as the permanence of racism.

Thirdly, framing is the ability to intentionally dismantle practices and policies that continue to uphold racism within schools. Educators need to reframe how they understand curriculum, assessment and evaluation practices, school discipline structures, and spaces where racialized students can talk openly and safely about their experiences of trauma in school settings. By reframing school structures, attention to deficit notions must be challenged—racialized students deserve to see themselves as worthy and excellent. In addition, framing focuses on moving beyond performative actions and instead uplifts, supports, and provides racialized students with a welcoming school environment.

The final step in the NOFS framework is sustaining the three aforementioned structures. By sustaining antiracist policies and practices, schools become a safer learning environment for everyone. Additionally, Lopez and Jean-Marie (2021) emphasize the importance of “collaborative mentorship”, in order to sustain antiracist actions. Dismantling racist structures is a journey that takes time and effort. Educators must be willing to be vulnerable in questioning the role they themselves play in schools while embracing the tensions involved in antiracist work. The NOFS framework meets educators where they are in their antiracist journey and provides a cushion for faculty to seek change. Saying you are an antiracist and implementing an antiracist framework will require sacrifices. Soltani (2017) insists that performative and tokenistic gestures will not bring about change.

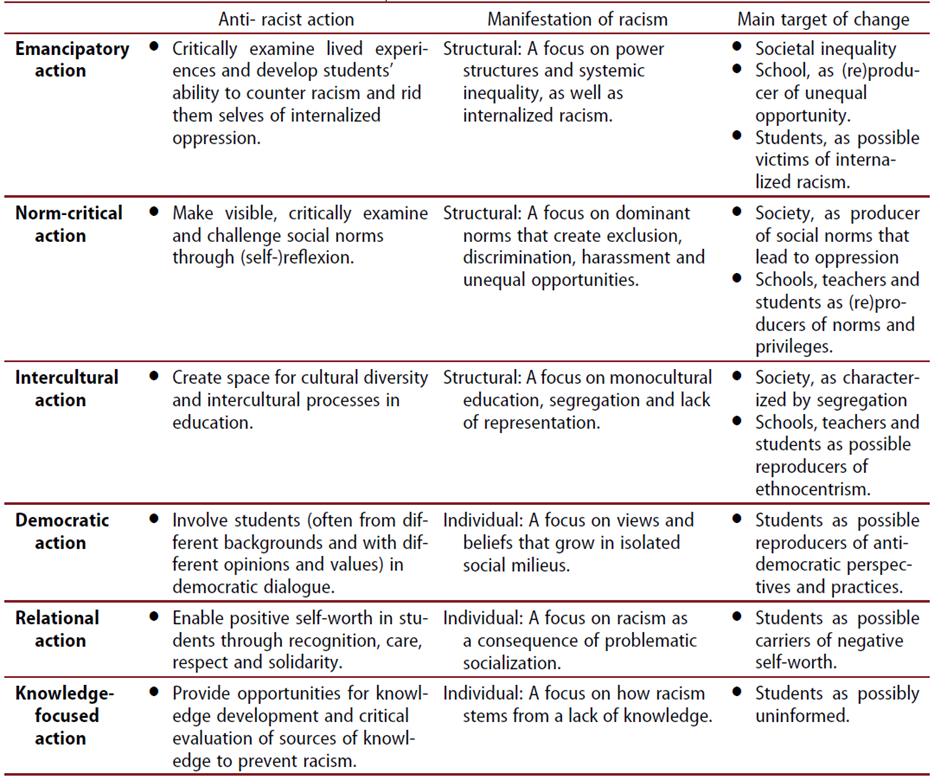

Typology Framework

There is no one-size-fits-all solution that can be applied to combat racism in school environments. Arneback and Jamte (2022) conducted an empirical investigation, drawing on the work of 27 teachers in the UK who all work to counteract racism in educational settings. Analyzing their qualitative research results, Arneback and Jamte (2022) produced a typology “that makes the complexity of both racism and antiracism visible and serves as a tool to help educators make active decisions regarding what type of antiracist action would best be used about the specific form of racism manifested” (p. 193). Figure 7 outlines six approaches to antiracist action and highlights the complexities of these approaches that educators might choose to engage in when dealing with the challenges of racism in schools.

This typology not only represents individual action but also provides a framework for dismantling structures within education. The breakdown between antiracist action and the manifestation of racism gives critical insight into counteracting and dismantling racial issues.

Figure 7

A typology of anti-racist actions (from Arneback & Jamte, 2022, p. 207).

Based on my findings from the literature review, I have conceptualized a framework that I feel holds faculty accountable for antiracist education. Inspired by the work of others (Arneback & Jamte, 2022; Kishimoto, 2022; Lopez & Jean-Marie, 2021), I synthesized and created the RAISE theory as a helpful tool for emerging and practicing educators to begin or continue on their antiracist teaching journey. I anticipate the RAISE theory (Figure 8) will be utilized as a safe tool to call individuals in, rather than call out. Most importantly, the RAISE theory invites teachers to rise up and put in the difficult work that antiracist education requires.

Figure 8

The RAISE Theory

Relationships

Relationships are integral to student learning—"if you can’t reach ‘em’, you can’t teach ‘em”. Teacher–student relationships are foundational for providing an antiracist education. In fact, “[p]ositive interpersonal relationships have been proposed as a buffer against stress and risk, instrumental help for tasks, emotional support in daily life, companionship in shared activities, and a basis for social and emotional development” (Marten, 2014, p. 10). Experiencing racism—overtly or explicitly—is traumatic and can have damaging results (Sue, 2010). Racialized students need to know they are loved, appreciated and seen for who they are. They need a judgement-free, compassionate, and safe place in school that allows them to talk about their experiences with racism. Although I have focused on the interpersonal relationship between teacher and student, racialized staff should be considered here as well.

To provide antiracist pedagogy in schools, educators must hold a high standard for themselves, school districts and boards of education. As mentioned above, dismantling race and racism is undoubtedly challenging—but not impossible. Performative measures are only tokenistic gestures that act as blanket statements. Raising flags, timely posts, or publicly announcing inclusive ideas are empty promises when followed up by the exclusion of antiracist actions. Boykin et al. (2020), assert that “combating systemic racism requires a transformation of the national education curriculum. Our call for education is very specific. Rather than additional implicit bias workshops that gesture broadly at discrimination, we call for a formal education on racism – an education that starts from elementary school and continues through high school” (p.779). Holding stakeholders accountable to produce policies embedded in antiracist theories is the way forward for a more equitable and just education system.

Solidarity amongst faculty in antiracist work acts as an invigorating measure for people – especially racialized groups. Racialized educators are not responsible for upholding antiracist accountability in schools (Boykin et al., 2020). Because those who face racism experience negative psychological and physiological effects (Boykin et al., 2020), non-racialized colleagues must help invigorate their racialized colleagues in the form of solidarity and allyship. In order to obtain solidarity, non-racialized educators must reflect on themselves and their position of power within school spaces.

In order for teachers to engage in antiracist work, they must first engage in self-reflexivity (Cole-Malott & Samuels, 2022). Schools continue to be hosts for maintaining power and privilege structures and therefore, one must first recognize, question, learn and unlearn their positionality. The process of self-reflexivity is foundational to The RAISE Theory. Cole-Malott and Samuels (2022) describe reflexivity as,

A process of questioning your unexamined assumptions about a wide range of ideas. It demands the interrogation of implicit bias and actively countering those biases when and where they are identified. Reflexivity asks you to step away from your thinking and to determine how your actions, beliefs, and practices shape outcomes as an educator. Reflexivity is actionable; it demands that you take action with what you know (p. 56).

Additionally, the audit tool aforementioned in the previous section can be utilized for self-reflexivity.

To effectively foster an antiracist environment, educators must first educate themselves to embrace antiracist pedagogy. Antiracist educators do not wait for resources to find them, they do not expect racialized groups to be experts in antiracist work, and finally, they are not selective in antiracist conversations. Antiracist education is a lens, a framework, and a critical worldview that allows others to seek and understand multiple perspectives. The RAISE Theory is an interconnected process that takes time, agency and commitment. In the words of Nelson Mandela, “education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world” (Cordeur, 2017, p. 45).

The scope of this literature review investigated the way racism shows up in education and the significance of antiracist education as it explores the possibility for other systems of oppression to be challenged. Using similar language from Bishop (n.d), antiracist education is good for racialized students and teachers and, therefore, good for all students and teachers.

There is an abundance of research, studies and findings defining antiracist education (Donaldson, 1997; Hasberry, 2013; James, 1995; Kishimoto, 2018; Ladson-Billings, 1995; Mutitu, 2010; Shah et al., 2022; Upadhyay et al., 2021), the need for antiracist education in learning spaces (Arneback & Jamte, 2022; Boulden & Borden, 2022; Boykin et al., 2020; Dei & Vickers, 1997; Goulet & Goulet, 2014; Lopez & Jean-Marie, 2021; Mark, 2003), and why antiracist education is so challenging, and in some cases, impossible (Gebhard et al., 2022; Kumashiro, 2000; Murray, 2020; Sleeter, 2017; Valencia, 2010; Vesley et al., 2023). Despite the challenges, we must acknowledge that education is the catalyst for change. Because “classrooms are the microcosms of the broader community and society” (Goulet & Goulet, 2014, p. 27), disrupting racism and questioning institutional power at the school level can have reflexive effects on society.

Finally, antiracist education is a framework for educators ready to disrupt institutional racism. Discreet or overt, racism continues to walk the halls, roam the playgrounds, and sustain power relations within classrooms. Racialized students and staff must feel heard, understood, and celebrated to continue to experience learning in positive ways. Patience, self-reflexivity and courage are fundamental attributes that make antiracist education attainable. In this way, Mark (2003) points out that antiracism practices are not "add-ons” to curricula, but rather a method of critically thinking and analyzing the world around us. By utilizing frameworks such as NOFS (Lopez & Jean-Marie, 2021) and The Raise Theory, faculty can uphold a standard to dismantle racial power dynamics in schools. We must commit to antiracist education to — up, with, and for, racialized groups who have yet to have their voice heard. Antiracist work is not racialized peoples’ work; antiracist work is all peoples’ work. To end, I leave you with a powerful quote from Ibram X Kendi (2019), “[w]e know how to be racist. We know how to pretend to be not racist. Now let’s know how to be antiracist” (p. 21). Let the work begin.

References

Andrews, D. J., He, Y., Marciano, J. E., Richmond, G., & Salazar, M. (2021). Decentering whiteness in teacher education: Addressing the questions of who, with whom, and how. Journal of Teacher Education, 72(2), 134-137. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487120987966

Angus Reid Institute. (2021). Diversity and education: Half of Canadian kids witness ethnic, racial bullying at their school. Angus Reid Institute. https://angusreid.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/2021.10.19_canada_school_kids_racism_diversity-1.pdf

Annamma, S. A., & Winn, M. (2019). Transforming our mission: Animating teacher education through intersectional justice. Theory Into Practice, 58(4), 318-327. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2019.1626618

Arneback, E., & Jämte, J. (2022). How to counteract racism in education – A typology of teachers’ anti-racist actions. Race Ethnicity and Education, 25(2), 192-211. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085916668957

Barreno, L. (2016). Global education in Saskatchewan schools. Community Research Unit, University of Regina. http://hdl.handle.net/10294/6747

Bedford, M. J., & Shaffer, S. (2023). Examining literature through tenets of critical race theory: A pedagogical approach for the ELA classroom. Multicultural Perspectives, 25(1), 4-20. https://doi.org/10.1080/15210960.2022.2162523

Bell, D. A. (1987). And we are not saved: The elusive quest for racial justice. Basic Books.

Berchini, C. N. (2017). Critiquing un/critical pedagogies to move toward a pedagogy of responsibility in teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 68(5), 463-475. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487117702572

Bishop, R. (n.d.). Te Kotahitanga: What's good for Maori. https://tekotahitanga.tki.org.nz/content/download/373/2342/version/10/file/good_for_maori_TKI+MP4.mp4

Bishop, R., Berryman, M., Tiakiwai, S., & Richardson, C. (2003). Te Kötahitanga: The experiences of year 9 and 10 Mäori students in mainstream classrooms. New Zealand: Ministry of Education.

Bonilla-Silva, E. (1997). Rethinking racism: Toward a structural interpretation. American Sociological Review, 62(3), 465-480. https://doi.org/10.2307/2657316

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2023). It's not the rotten apples! Why family scholars should adopt a structural perspective on racism. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 15(2), 192-205. https://doi-org.libproxy.uregina.ca/10.1111/jftr.12503

Boulden, R., & Borden, N. (2022). Voices from the field of school counseling: Promoting anti-racism in school settings. In K. F. Johnson, N. M. Sparkman-Key, A. Meca, & S. Z. Tarver (Eds.), Developing anti-racist practices in the helping professions: Inclusive theory, pedagogy, and application (pp. 305-327). Palgrave Macmillan Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-95451-2_15

Boykin, C. M., Brown, N. D., Carter, J. T., Dukes, K., Green, D. J., Harrison, T., ... & Williams, A. D. (2020). Anti-racist actions and accountability: Not more empty promises. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 39(7), 775-786. https://doi-org.libproxy.uregina.ca/10.1108/EDI-06-2020-0158

Brookfield, S. D. (2017). Becoming a critically reflective teacher (2nd edition). Jossey-Bass.

Browne, S., Jean-Marie, G., Onofre, Y., & Dai, Y.-J. (2023). A deep dive: Reconceptualizing social justice in teacher education. In S. Browne & G. Jean-Marie (Eds.), Reconceptualizing social justice in teacher education: Moving to anti-racist pedagogy (pp. 3-20). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-16644-0_1

Calderon, D. (2006). One-dimensionality and whiteness. Policy Futures in Education, 4(1), 73-82. https://doi.org/10.2304/pfie.2006.4.1.73

Cole-Malott, D.-M., & Samuels, S. “. (2022). Becoming a culturally relevant and sustaining educator (CRSE): White pre-service teachers, reflexivity, and the development of self. In S. Browne & G. Jean-Marie (Eds.), Reconceptualizing social justice in teacher education: Moving to anti-racist pedagogy (pp. 39-62). Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-16644-0_3

Cordeur, M. L. (2017). Mandela and Afrikaans: From language of the oppressor to language of reconciliation. In C. S. (Ed.), Nelson Mandela (pp. 45–61). Sense Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6300-908-9_5

Dei, G. J., & Vickers, J. (1997). Anti-racism education: Theory & practice. Journal of Canadian Studies, 32(2), 175-182.

Delgado, R., & Stefancic, J. (2017). Critical race theory: An introduction (3rd edition). New York University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1ggjjn3

DiAngelo, R. (2011). White fragility. The International Journal of Critical Pedagogy, 3(3), 54-70.

Donaldson, K. B. M. (1997). Antiracist education and a few courageous teachers. Equity and Excellence in Education, 30(2), 31-38. https://doi.org/10.1080/1066568970300204

Efimoff, I. H., & Starzyk, K. B. (2023). The impact of education about historical and current injustices, individual racism and systemic racism on anti-Indigenous racism. European Journal of Social Psychology, 53(7), 1542-1562. http://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2987

Fryer, R. G., & Levitt, S. D. (2004). The causes and consequences of distinctively black names. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(3), 767-805. https://doi.org/10.1162/0033553041502180

Gebhard, A., Mclean, S., & St. Denis, V. (2022). White benevolence: Racism and colonial violence in the helping professions. Fernwood Publishing.

Gillborn, D. (2015). Intersectionality, critical race theory, and the primacy of racism: Race, class, gender, and disability in education. Qualitative Inquiry, 21(3), 277–287. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800414557827

Goulet, L. M., & Goulet, K. N. (2014). Teaching each other: Nehinuw concepts and Indigenous pedagogies. UBC Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780774827591

Hambacher, E., & Ginn, K. (2021). Race-visible teacher education: A review of the literature from 2002 to 2018. Journal of Teacher Education, 72(3), 329-341. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487120948045

Hampton, R. (2016). Racialized social relations in higher education: Black student and faculty experiences of a Canadian university. (Publication No. 28250488) [Doctoral dissertation, McGill University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Hantke, S. (2022). Unmasking the Whiteness of nursing. In A. Gebhard, S. McLean, & V. St. Denis, (Eds.), White benevolence: Racism and colonial violence in the helping professions (pp. 170-199). Fernwood Publishing.

Hasberry, A. (2013). Black teachers, white schools: A qualitative multiple case study on their experiences of racial tokenism and development of professional black identities. [Doctoral Dissertation, University of Nevada]. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/4478254

Hickling‐Hudson, A., & Ahlquist, R. (2003). Contesting the curriculum in the schooling of Indigenous children in Australia and the United States: From eurocentrism to culturally powerful pedagogies. Comparative Education Review, 47(1), 64-89. https://doi.org/10.1086/345837

James, C. E. (1995). Multicultural and Anti-Racism Education in Canada. Race, Gender & Class, 2(3), 31-48. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41674707

Jayakumar, U. M., & Adamian, A. S. (2017). The fifth frame of colorblind ideology: Maintaining the comforts of colorblindness in the context of white fragility. Sociological Perspectives, 60(5), 912-936. https://doi.org/10.1177/0731121417721910

Kay, M. R. (2018). Not light, but fire: How to lead meaningful race conversations in the classroom. Stenhouse Publishers. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781032681870

Kendi, I. X. (2019). How to be an antiracist. One World.

King, E. T. (2023). Envisioning spaces of anti-racist pedagogy in teacher education programs. In S. Browne, & G. Jean-Marie, (Eds.), Reconceptualizing social justice in teacher education: Moving to anti-racist pedagogy (pp. 21-38). Palgrave MacMillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-16644-0_2

Kishimoto, K. (2018). Anti-racist pedagogy: From faculty's self-reflection to organizing within and beyond the classroom. Race Ethnicity and Education, 21(4), 540-554. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2016.1248824

Kishimoto, K. (2022). Beyond teaching racial content: Antiracist pedagogy as implementing antiracist practices. In S. Browne, & G. Jean-Marie, (Eds.), Reconceptualizing social justice in teacher education: Moving to anti-racist pedagogy (pp. 105-125). Palgrave MacMillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-16644-0_6

Kohli, R. (2009). Critical race reflections: valuing the experiences of teachers of color in teacher education. Race Ethnicity and Education, 12(2), 235-251. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613320902995491

Kohli, R., & Solorzano, D. G. (2012). Teachers, please learn our names! Racial microaggressions and the K-12 classroom. Race Ethnicity and Education, 15(4), 441-462. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2012.674026

Kumashiro, K. K. (2000). Toward a theory of anti-oppressive education. Review of Educational Research, 70(1), 25-53. https://doi.org/10.2307/1170593

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 465-391. https://doi.org/10.2307/1163320

Ladson-Billings, G., & Tate, W. F. (1995). Toward a critical race theory of education. Teachers College Record, 97(1), 48-68. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146819509700104

Leonardo, Z. (2004). The colour of supremacy: Beyond the discourse of 'white privilege'. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 36(2), 137-152. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-5812.2004.00057.x

Lopez, A. E., & Jean-Marie, G. (2021). Challenging anti-black racism in everyday teaching, learning, and leading: From theory to practice. Journal of School Leadership, 31(1-2), 50-65. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052684621993115

Love, B. L. (2019, March 18). Dear white teachers: You can't love your black students if you don't know them. Education Week, 38(26), 512-523.

Luft, R. E. (2010). Intersectionality and the risk of flattening difference: Gender and race logics, and the strategic use of antiracist singularity. In M. T. Berger, & K. Guidroz (Eds.), The intersectional approach: Transforming the academy through race, class, and gender (pp. 100-117). University of North Carolina Press.

Mark, K. (2003). An argument for anti-racism education for school personnel. Orbit, 33(3), 1-6.

Moreton-Robinson, A. (2015). The White possessive: Property, power, and indigenous sovereignty. University of Minnesota Press. https://doi.org/10.5749/minnesota/9780816692149.001.0001

Murray, T. A. (2020). Microaggressions in the classroom. Journal of Nursing Education, 59(4), 184-185. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20200323-02

Mutitu, M. W. (2010). Feeling the race issue: How teachers of colour deal with acts of racism towards them. [Doctoral Dissertation, University of Victoria]. Electronic Theses and Dissertations. http://hdl.handle.net/1828/3021

Nieto, S. (2000). Placing equity front and center: Some thoughts on transforming teacher Education for a New Century. Journal of Teacher Education, 51(3), 180–187. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487100051003004

Partridge, K. E. (2014). Schooling for colonization and white supremacy: Failures of multicultural inclusivity. [Master’s thesis, University of Toronto]. ProQuest Dissertations and Thesis Global. https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/67877/1/Partridge_Kate_E_201406_MA_thesis.pdf

Pierce, C. (1970). Offensive mechanisms. In F. B. Barbour (Ed.), The Black seventies (pp. 265-282). Porter Sargent.

Pierce, C. (1974). Psychiatric problems of the Black minority. In S. Arieti (Ed.), American handbook of psychiatry (pp. 512-523). Basic Books.

Pierce, C. M., Carew, J. V., Pierce-Gonzalez, D., & Wills, D. (1977). An experiment in racism: TV commercials. Education and Urban Society, 61-87. https://doi.org/10.1177/001312457701000105

Robinson, E. C. (2005). Studying the representation of black and other racialized and minoritized teachers in the Canadian education system: An antiracist pedagogical approach. [Doctoral Dissertation, University of Toronto]. UMI.

Ryan, W. (1971). Blaming the victim. Random House.

Scheff, T. J. (2000). Shame and the social bond: A sociological theory. Sociological Theory, 18(1), 84-99. https://doi.org/10.1111/0735-2751.00089