Centering Social Justice and Well-Being in FSL Teacher Identity Formation to Promote Long-Term Retention

Mimi Masson, Université de Sherbrooke

Alaa Azan, Independent Researcher

Amanda Battistuzzi, University of Ottawa

Authors’ Note

Mimi Masson https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1516-4601

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Mimi Masson at mimi.masson@usherbrooke.ca

Abstract

The French as a second language (FSL) teacher shortage crisis has been a longstanding issue in Canada. In this paper, we examine the links between teacher agency, autonomy and identity in light of findings about marginalization, deprofessionalization, and/or difficulty in developing a strong sense of identity. Taking these findings into account, we propose an FSL teacher preparation model rooted in social justice and well-being which centers identity development through four pillars for success: language proficiency, intercultural competence, pedagogical knowledge and skill, and collaborative professionalism. We examine the implications of taking such an approach in FSL teacher preparation and argue that applying a social justice lens to identity development sets FSL teachers up for effective professionalization and a sense of well-being that can lead to long-term retention in the field.

Keywords: French as a second language, language teacher identity, teacher retention, social justice, well-being

Centering Social Justice and Well-Being in FSL Teacher Identity Formation to Promote Long-Term Retention

Over the last decade, French as a Second Language (FSL) programs have become more popular with parents (Canadian Parents for French, 2020). Currently, FSL[1] is taught across a variety of programs, including core French, French immersion, and intensive French. However, FSL teacher shortages have been a longstanding issue across Canada (Wernicke et al., 2022). With chronic FSL teacher attrition a threat to healthy FSL programs, what are we overlooking in terms of understanding the complex political and social forces at play when it comes to supporting FSL teachers for long-term success in the profession? What does the application of a social justice lens throughout the teacher preparation process reveal about issues that may improve FSL teachers’ overall sense of autonomy, agency, and well-being?

At the request of the Canadian Association of Second Language Teachers (CASLT), we investigated effective additional language (L+) teacher preparation (Masson et al., 2021) and additional language teacher attrition, retention, and recruitment (Masson & Azan, 2021). The main objective was twofold: 1) conduct a literature review on the skills future teachers need to become effective L+ teachers, and 2) examine factors unique to language teachers that contribute to teacher attrition to make recommendations for retention and recruitment. The research sought to address these questions for all language teachers, with a special focus on FSL teachers. Details about the methodological process for creating the literature review, which counted 122 sources, can be found in the CASLT reports.

As teacher educators and educational researchers, we felt it would be useful to put this information in conversation with our ongoing experiences in FSL teacher education programs and to filter these results more broadly through a social justice lens. As such, this paper seeks to:

1.Present a model for FSL teacher preparation that responds to the socio-political context that teachers and teacher education programs find themselves in.

2.Critically examine the interconnection between FSL teacher preparation and teacher retention.

By placing FSL teacher professional identity as the lynchpin to effective teacher preparation (Fairley, 2020; Morgan, 2004), we can address retention based on the idea that “the process of attrition begins long before teachers leave the profession” (Schaefer et al., 2012, p. 115). In the following sections, we first look at what we can learn from the literature on teacher attrition; next, we introduce L+ teacher identities as a way to understand the connection between attrition and professionalization. From this, we then introduce a model for FSL teacher preparation and critically discuss how its components might be addressed in teacher education programs with a view to supporting long-term retention.

Causes and Impacts of Teacher Attrition

Teacher attrition, which refers to teachers’ decision to leave the classroom, can be organized into hidden attrition and voluntary attrition (Mason, 2017). Hidden attrition occurs when teachers move from teaching their subject to working as school administrators and consultants, or in the case of FSL teachers, working in English-language streams only—that is, no longer teaching French. Hidden attrition is a major challenge to FSL teacher retention, though we have little to no data to confirm this beyond anecdotal observations. Voluntary attrition is when teachers leave the profession entirely. A national study from two decades ago reported that up to 40% of FSL teachers end up leaving or consider leaving the profession at one point in their careers (Lapkin et al., 2006)

From a systems perspective, teacher attrition is a financial and programmatic drain on schools. It results in financial and professional costs to the educational system (OECD, 2020, as cited in Madigan & Kim, 2021). Financially, as more teachers leave the profession, more time and resources are needed to train new teachers. Educationally, because schools continue to hire new teachers, it becomes challenging to create a community, making schools less efficient in promoting student success. In particular, teacher turnover impacts students’ academic achievement and overall staff performance; that is, “new teachers have lesser qualifications and experience than the departing teachers” (Sorensen & Ladd, 2020, p. 14), meaning precious institutional memory is lost every time a teacher leaves the profession. Many factors contribute to teacher attrition, such as burnout (Madigan & Kim, 2021) and teachers’ sense of self-efficacy (De Neve & Devos, 2017; Parks, 2017).

The years spent in teacher education programs are an inherent part of teachers’ professionalization, which refers to the process of becoming a teacher. It includes building a teacher knowledge base, moving through a process of socialization that centers around developing values, responsibilities, ways of being as a teacher, and establishing a sense of identity and belonging in the profession (Ingersoll, 1997). Teacher professionalization is linked to the commitment teachers feel towards their chosen profession (Ingersoll, 1997), indicating that “professionalization could be helpful to stimulate teachers’ job motivation and with that retain and maintain teachers for the job” (Hofman & Dijkstra, 2010, p. 1038). In the case of FSL teachers, attrition may be linked to a growing sense of deprofessionalization, which is a feeling that teachers can get when they lose their sense of agency and control over their work (Biesta, 2007). A particular point of interest is that,

Teacher learning is seen to involve the adoption of a teacher identity, a process that involves an interaction between the teaching and learning processes of the teacher-education learning site and the individual teacher’s own desire to find meaning in being a teacher (Richards, 2016, p. 139).

In sum, this identity formation, during the FSL teacher preparation years, is deeply interconnected with teacher agency and autonomy.

Language Teacher Identity Formation

Teacher preparation programs are often the place where teachers begin to develop their language teacher identities (LTI) (i.e., who they are as FSL educators). In these programs, they encounter ideas about what language is, what learning is, how to teach language, and how to teach generally. Along the way, language teachers must develop a vast repertoire of knowledge about the target language, language more broadly speaking, language acquisition theory, and pedagogy, specific to their subject matter and more broadly. Approaches to how they learn in these programs and how they are positioned as educators then set the stage for them as they enter the professional sphere. Teacher autonomy, which represents their ability to make informed choices in their professional context, develops alongside their identity (Teng, 2019). Autonomy has a direct impact on identity formation: “Teachers who are unable to assert professional freedom may embrace a fragile identity. Teachers who are incompetent and reluctant to take control of their teaching may have a rigid identity” (Teng, 2019, p. 84). Another important aspect of autonomy is collective autonomy, a tenet of collaborative professionalism (Hargreaves & O’Connor, 2018), the idea that teachers should feel “autonomous from the system bureaucracies but less autonomous from each other” (Hargreaves & O’Connor, 2018, p. 110) to succeed in the profession.

Agency, another key aspect of LTI (Kayi-Aydar, 2015), affects not only teachers’ own learning but also the learning environments they can generate. Indeed, when agency is constrained, teachers struggle to remain openly vulnerable with their students and create trusting learning environments (Lasky, 2005). Agency is not solely located within the individual. For teachers, it also develops as a collective when they work and network with others in their professional environments. To enhance continuous professional learning and organizational change, individual and collective agency must be supported.

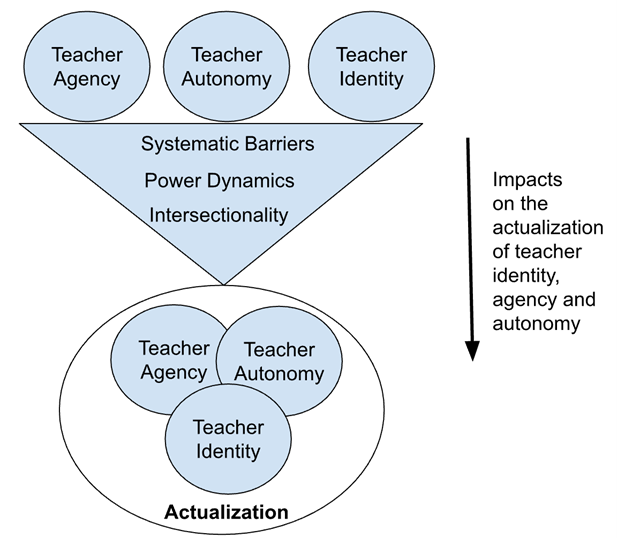

The teacher education context is an important site for the development of teacher identity, autonomy, and agency to model how “their identities may be negotiated and may prevent [their] identity as a teacher from collapsing within a site of struggles and constraints” (Teng, 2019, p. 84). We add to Teng’s (2019) model for teacher identity actualization, the notion that for L+ teachers, negotiating their identity also entails navigating a complex entanglement of beliefs about knowledge, learning, language, and social identities (Lynch & Motha, 2023). Therefore, teacher educators need to recognize the interconnectedness between teacher identity, autonomy, and agency in their efforts to support the professionalization process and to do this considering social justice factors, such as systemic barriers, power dynamics, and intersectionality of identities, as depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1

The Actualization of Teacher Professional Identities Filtered Through Systemic Barriers, Intersectionality and Power Dynamics

We understand LTIs as transformative and in the process of transformation: constantly undergoing discursive (re)/(de)construction that is embodied and socially mediated through self-reflection and collaboration with peers. We locate LTI at the intersection of professional socialization (i.e., teacher learning) and language socialization (i.e., participation in linguistic communities). As Vygotsky argued, it is “essential to incorporate the study of human culture and history into the effort to understand the development of the human mind.” (cited in Swain & Deters, 2007, p. 821). We see this as the impetus for turning our gaze to LTI when it comes to addressing L+ teacher learning and long-term retention in the profession (Parks, 2017). If L+ teacher learning occurs through relationship building, then a holistic approach to understanding and developing teacher identities (Schaefer et al., 2012) will provide much needed insight into the links to FSL teacher attrition.

Additional Language (L+) Teacher Identity Formation: Implications for FSL Teachers

Additional language teacher professional identity is an important focus in teacher education as it permeates all areas of educational life: how teachers teach, how they interact with students, how they interact with parents, what role they see themselves playing in the classroom, in their schools, and in their communities, etc. Norton defines it as “the way a person understands [their] relationship to the world, how that relationship is structured across time and space, and how the person understands possibilities for the future” (Norton, 2013, p. 4). Such a definition underscores the importance of truly understanding how FSL teachers situate themselves in their practice and the profession more broadly to even begin to attempt to counter attrition rates and improve retention.

Much of the research on FSL language teacher identity in Canada has focused on their linguistic identity, namely how FSL teachers, many of whom are L+ learners of French themselves, construct their identity around the notion of ‘native-speakerness’ (Tang, 2020; Wernicke, 2017). Other research has examined how to support FSL teachers’ competence and confidence in their language proficiency as it relates to their professional and linguistic identity (Le Bouthillier & Kristmanson, 2023). While prior research has framed the ‘non-native’ speaker identity, namely among white anglophone teacher candidates, as a hurdle to achieving full linguistic and professional competence (Bayliss & Vignola, 2007), more recent research has attempted to move beyond the ‘native-speaker / non-native-speaker’ paradigm (Wernicke, 2020) to examine the professional identity construction of FSL teachers more holistically.

Other research has sought to move beyond ‘native-speaker’ ideologies by adopting a plurilingual stance and acknowledging the multiple partial plurilingual repertoires of future FSL teachers (Byrd Clark & Roy, 2022). This research has further problematized the portrayal of FSL teachers’ linguistic identities by accounting for their plurilingual profiles and how that might affect their approach to teaching French (Byrd Clark, 2008). Understanding the relationship between teacher identities and agency reveals the ongoing discursive negotiation of the relationship to language over time (Kayi-Aydar, 2015), allowing teachers to challenge static notions of native-speakerism.

Beyond the connections individuals make to the language they choose to teach, questions also arise about how language teachers are positioned in their practice: How their social, racial or cultural identities intersect and affect their status (Ramjattan, 2019). Most concerning, in our case, is the research in language teacher attrition which shows that racially and socially marginalized teachers are at greater risk of deprofessionalization and departure from the profession than teachers who identify as white, cis-gender, heterosexual, able-bodied, among other dominant social markers (Ingersoll et al., 2019; Marx et al., 2023). Given the increasing changes in the makeup of student populations, it is essential to make efforts to retain members of the teaching profession who reflect linguistic, cultural, and racial diversity among other social identity markers, such as gender, sexual orientation, religious affiliation, immigration status, and (dis)ability.

More recent research has sought to examine the intersection of race with the professional identity construction of FSL teachers, particularly as these identities intersect with the unique linguistic policy of official bilingualism in settler colonial Canada (Masson & Côté, 2024; Wernicke, 2022). These constitute an emerging body of work moving beyond a purely linguistic focus to add other frameworks that consider the intersectionality of linguistic identities with other social, ethnic, and/or cultural identities (in these cases, racial and citizenship/immigration-based identities).

Focusing more explicitly on FSL teachers’ professional identities, some research has examined their overall sense of efficacy (Cooke & Faez, 2018), professional belonging and well-being (Knouzi & Mady, 2014; Masson, 2018), and how collaborative practices influence their sense of professionalism (Kaszuba et al., in press). The results, although demonstrating great creativity and resilience among some FSL teachers, also point to a greater need for teachers to build strong professional identities, which will, in turn, affect teachers’ decisions to remain in the profession long-term.

More recent and alternative approaches to developing FSL teacher identity have focused on intentionally working with future FSL teachers through transformative arts-based research paradigms to address their linguistic, cultural and professional identities agentively as a means to identify and (re)/(de)construct deep-seated beliefs about language, learning and teaching with future FSL teachers (Masson & Côté, under review).

FSL Teacher Preparation for Long-Term Retention

A growing body of research has highlighted the crucial links between teacher learning and LTI formation (Xu, 2017), pointing to a need for teacher education programs to center teacher identities during the teacher preparation process (Fairley, 2020). Identity-based language teacher education pedagogies make space for taking into consideration social justice issues that will impact language teachers’ professional identity development (Varghese, 2016; Cochran-Smith & Keefe, 2022). We argue that centering language teacher identities can be a means of preparing FSL teachers to enter the profession and remain in the long run. As we will show over the next sections, identity permeates all key facets of language teacher preparation, making it imperative to center identity development in language teacher preparation programs.

Among other important aspects that support the development of strong FSL teacher professional identities is understanding how teachers negotiate institutional demands and contexts in which they find themselves. A pan-Canadian study led by Stephanie Arnott to identify ways to better equip new FSL teachers for long-term success found that systemic issues create a metaphorical ‘avalanche’ that overwhelms many teachers, forcing them to consider leaving the profession (CASLT, 2022). Colleagues on the project, Culligan et al. (2023) and Wernicke et al. (2022) identified language proficiency support, professional collaboration and mentorship as means to support FSL teacher retention further.

Recent research (Cook & Faez, 2018) has revealed that FSL teacher candidates do not always feel particularly confident in delivering instruction upon completion of their teacher education programs. Core to the impetus for this paper is the notion that the structure of FSL teacher education programs may be negatively affecting future FSL teachers’ preparational needs for long-term success in the profession (see Smith et al., 2023 for details on the structure of programs across Canada). Structural challenges in teacher education programs include deficit-oriented perspectives, limited time and access to material and human resources, lack of relational approaches to teaching and collective responsibility toward FSL teacher preparation (CASLT, 2022). Prior research has identified further areas that affect individual FSL teachers’ self-efficacy (Faez, 2011), including linguistic and cultural background, language proficiency in French, and their beliefs about language and learning. We suggest that FSL teacher educators and researchers reflect critically on the pathways, content and culture of learning and teaching offered and modelled in programs to support self-efficacy and the development of strong professional identities among future FSL teachers.

To examine more closely how LTI permeates FSL teacher learning specifically, we propose an FSL teacher preparation model based on decades of research on teacher learning and preparation. For instance, Lapkin et al. (1990) set an agenda for French immersion teacher education, which pointed to a need for both general teacher preparation and specific immersion education components – highlighting the uniqueness of preparing FSL teachers for certain contexts. Later, MacFarlane and Hart (2002) elaborated on what FSL teachers should receive in their initial education program: pedagogical qualifications, subject matter knowledge, and language proficiency. Salvatori and MacFarlane (2009) suggest that the knowledge base of the language teacher should include “theories of teaching, teaching skills, communication skills, subject matter knowledge, pedagogical reasoning and decision making, and contextual knowledge” (p. 6). This is reflective of the broad areas of knowledge and skills identified in research that contribute to effective additional language teaching (Freeman & Johnson, 1998) while making specific recommendations for FSL teacher preparation.

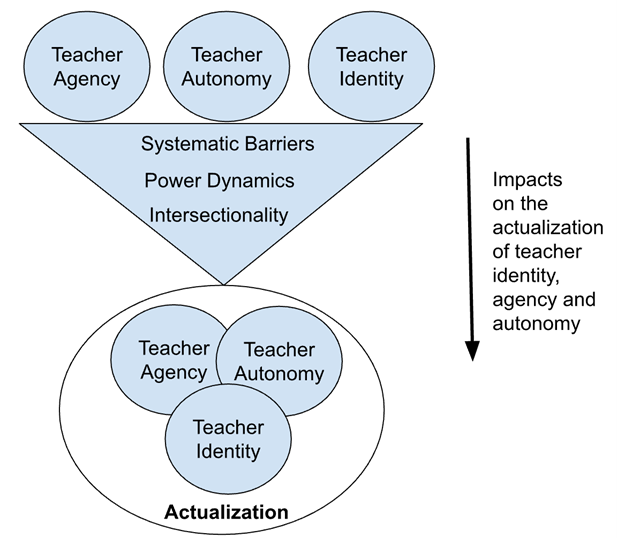

Taking the literature on L+ teacher education into account, we present a holistic approach we are calling the Four Pillars for Success specific to FSL teacher needs, which highlights the development of language teacher competence across four key areas: 1) target language proficiency, 2) intercultural competence, 3) pedagogical knowledge and skill, and 4) collaborative professionalism. The pillars were identified as ways to promote effective FSL teaching and provide a guided approach to lifelong learning. These pillars do not stand alone; they are dependent on each other, and improvements in one area will likely impact the others.

The first three pillars reflect the literature on L+ education as pieces that contribute to effective L+ teaching (Freeman & Johnson, 1998; Salvatori & MacFarlane, 2009). In FSL teacher preparation programs, French language proficiency is often evaluated before FSL teacher candidates enter their teacher education programs (Bayliss & Vignola, 2007). In some cases, it is also maintained through French coursework and language courses. Intercultural competence, which is the capacity to mediate between languages and cultures as they come into contact, is often addressed to some extent in programs, with varying degrees of success depending on how the notion of culture is discussed, how much teacher candidates think about and interact with the colonial past and present of the French language, and how varieties of French are discussed or absent during the program (Masson et al., 2022). Teacher education programs cover basic overarching and subject-specific pedagogical knowledge and skills, particularly in FSL methodology courses. We have added collaborative professionalism (Hargreaves & O’Connor, 2018) to the framework as a response to the specific professional learning needs of FSL teachers. As many FSL teachers report feeling isolated within their schools (Knouzi & Mady, 2014; Masson, 2018), this pillar emphasizes the importance of working with and learning from other teaching professionals to develop collective efficacy, autonomy, and a shared vision for effective language teaching. Together, these four pillars, presented in Figure 2, form an important set of skills and professional mindset that link to the idea of teachers as lifelong learners such that their professional identity and well-being become the central focus in hopes of addressing long-term teacher retention in the profession.

Figure 2

The Four Pillars for Success in FSL Teacher Education

The model is based on our research and professional experiences working as FSL teachers and teacher educators. Research and conversations with other FSL teacher educators have also greatly informed the development of this model. With this in mind, we also took into account two important factors when designing the model. First, it is important to acknowledge that FSL teachers in Canada have unique preparational needs due to the fact that many of them work bilingually within a monolingual framework (i.e., they teach in French and work in English-language school boards). Second, when it comes to developing a preparational model for teachers, teacher training programs in Canada are situated within their own unique historical, political and cultural context. This informs the professional environment teachers will be entering upon graduation. For instance, in Canada, a low valuation of French as a subject across school boards contributes in part to the ongoing FSL teacher shortage (Lapkin et al., 2006; Masson, 2018). FSL teachers report feeling a sense of deprofessionalization, meaning that their practice and professional judgment are undervalued (Lapkin et al., 2006). FSL teachers in Canada report that their status can be undermined based on whether they are perceived as ‘native’ speakers of French (Wernicke, 2017). FSL teachers’ racial identity also intersects with their ‘native-/non-native’ speaker identity, often revealing deep-rooted racism and discrimination (Masson & Côté, 2024).

Studies we examined across the four pillars highlighted the intersection of preparation, practice, and identity formation for new FSL teachers. While teacher education programs often deal with the first two prongs, identity formation is not always explicitly addressed or developed, particularly as it relates to L+ teacher identity and their mental, emotional, and physical well-being. In the following section, we define each of the pillars and critically discuss the implications of these definitions in light of the studies we reviewed. We include some possible recommendations, but we want to note that approaching initial teacher education (ITE) from a socially just and equitable perspective means that faculties should develop modifications for their programs that account for the unique contextual needs and profiles of their teacher candidates. The recommendations are intended as possible examples rather than advocating for any kind of ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to ITE for L+ language teachers. Incorporating LTI development in teacher preparation models is what might help us address FSL teacher attrition and improve retention in the profession.

Language Proficiency

Under this holistic model, language proficiency is just that: a measure of proficiency rather than deficiency. Taking a socially mediated approach to language learning, language proficiency becomes an interactive skill that happens within and is influenced by social and cultural contexts in which it is being used. Pinpointing levels of proficiency, then, also becomes dynamic as it depends on how the language is used in a given context. As knowledge is co-constructed, language proficiency can only be evaluated and re-evaluated on a continuous basis, rather than determined and held at a certain point in time.

Conceptualizations of language and language learning that are rooted in pluralistic frameworks, such as those that promote plurilingual competence or translanguaging, align with more holistic understandings of language learning. They are anchored in an asset-based perspective to language learning and favour approaches to language learning that draw on learners’ linguistic and cultural funds of knowledge as a starting point.

Naturally, the level of language proficiency in French matters for future FSL teachers. Language proficiency is closely related to identity and affects teachers’ sense of self. How they develop their sense of expertise in this area is crucial, and for this, it is essential to consider future FSL teachers’ linguistic identity. L+ teachers' identities have long been constructed around the notion of ‘native’ / ‘non-native’ speakers. This conception of linguistic identity has been problematized (Canagarajah, 2013) for being an oversimplification rooted in a monolingual paradigm that often excludes racialized teachers and those from the Global South (Pillay, 2018; Ramjattan, 2019).

In the FSL context, this ideology continues to impact teachers negatively (Wernicke, 2017, 2020). It is problematic as it can create feelings of linguistic insecurity among FSL teachers (Wernicke, 2020, 2023), or what Tang and Fedoration (2022) have rebranded as a lack of ‘linguistic security’ to take an asset-based approach towards the healing and legitimizing work that FSL teachers who are L+ learners of French must embark on to feel a sense of belonging to their professional context. They also highlight the way in which discussions around ‘linguistic insecurity’ are rooted in deficit-oriented perspectives when they attribute teachers with the primary responsibility for not feeling ‘secure enough’ to teach effectively or stay in the profession (Tang & Fedoration, 2022). In reality, L+ FSL teachers are regularly confronted with monolingual and exclusionary discourses in the media, in schools, from parents, and in programs, about who can speak/teach French and what those speakers should look and sound like (Masson & Côté, 2024). This perspective is reinforced in teacher training programs (Masson et al., 2022), where L+ FSL teachers’ language proficiency is policed, and tests are used as a gatekeeping measure[2].

In the Canadian context, the notion of ‘native speaker’ is often tied to the idea of being ‘francophone’, ‘anglophone’ and/or ‘bilingual’. However, linguistic identity markers such as francophone, anglophone and bilingual can reinforce divides between teachers and entrench feelings of ‘otherness’ among L+ teachers (Riches & Parks, 2021; Tang & Fedoration, 2022). Francophone communities have unique cultures and settler colonial histories that are part of the Canadian landscape. While ‘francophone-ness’ has long been associated with whiteness and portrayed through a Eurocentric lens (Wernicke et al., in press), speakers of French in Canada are actually present in every province and territory in the country, including in some Indigenous and Métis communities. What is more, the francophone community as a whole in Canada has undergone large ethnic, racial and cultural shifts in the last decades, in part due to the migratory movements of many speakers of French from the African, Asian, and South American/Caribbean diaspora (Madibbo, 2021). Many L+ French teachers struggle to identify as francophone, bilingual, or even plurilingual, and how these identities are taken up intersect in complex and nuanced ways when racial, ethnic, and cultural identities are also taken into consideration (Wernicke, 2022; Masson & Côté, 2024).

Recommendations

As teacher candidates come from diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds, efforts to improve FSL teachers’ language proficiency should draw from teachers’ resources in their language support efforts. For this, conceptions of FSL teachers’ linguistic identity need to be revisited. While researchers have moved away from the conceptualization of FSL teachers as ‘native’/’non-native’ speakers, it remains unclear whether and to what extent this notion is reinforced and/or deconstructed with teacher candidates in preparation programs. For this, FSL teacher educators need to look inward at the linguistic ideals they are reproducing in their programs. One recent exemplary study shows how three FSL teacher educators deconstruct their understanding of linguistic identity in their local context and how this affects their practice in teacher preparation programs (Tang et al., 2023). Reframing FSL teachers as additional language (L+) speakers can account for their plurilingual and pluricultural experiences. In fact, L+ speakers of French make up the majority of FSL teachers in some provinces (ACPI, 2018). Taking an asset-based perspective towards the language proficiency and capacity to speak multiple languages among FSL teachers would not only enhance their self-efficacy but also create a shift that empowers teachers to explore their own and their students’ linguistic repertoires holistically. Taking an intersectional lens to linguistic identity can also account for intersections with cultural, ethnic, racial, and immigrant/settler identities to reveal unique life trajectories and learning needs. For instance, most FSL teachers find themselves in predominantly anglophone contexts, where they have fewer opportunities to use French. They may have had linguistic journeys in which they made more or less use of their French at different points in their life, or they may come from international contexts and need to familiarize themselves with local varieties of French in order to teach in Canada. The argument, here, is to expand our understanding of FSL teacher candidates as simply ‘native speakers’ or ‘non-native speakers’ since reality often shows that this categorization is too limiting to encompass the wide array of FSL teacher candidates’ linguistic profiles, in turn delegitimizing their identities as language speakers (Wernicke, 2020).

Teacher education programs need to consider what experiences they offer their students to improve their linguistic proficiency and how they position teacher candidates throughout these offerings. The short duration of ITE programs and insufficient immersive experiences hinder their linguistic gains (Roskvist et al., 2014). Addressing this would require providing authentic, intensive, immersive experiences in French communities to support their proficiency and confidence throughout all phases of the teacher education program, including coursework and practicum (Culligan et al., 2023; Masson et al., 2019).

Intercultural Competence

Teaching languages also means being able to teach how to mediate between cultural groups as they come into contact during communicative exchanges. Intercultural competence (IC) is tied to language teaching in that stronger cultural knowledge supports language learning (Ruest & Wernicke, 2021). The prongs of IC have been defined in various ways but generally encompass some or all of the following components: awareness and understanding of cultural differences, experience with other cultures, and understanding of one’s own culture. It has also been defined as a set of skills, knowledges and attitudes (Byram, 1997). For teachers, this knowledge combined with language proficiency, can lead to language teaching that is in tune with how learners take up language usage in different contexts.

Language teachers not only need to develop their own IC, but they also need to learn how to teach it in their classrooms and develop intercultural teaching and learning (ICTL). This means that FSL teachers must have a good understanding of themselves as cultural beings, an awareness of the plethora of French cultures in Canada and across the world and be able to acknowledge and interact adeptly with the presence of local cultures in their professional context (i.e., their students’ cultures, the local community’s cultures). However, language teachers do not always understand their role and responsibilities as reproducers of cultural or linguistic models (Keating Marshall & Bokhorst-Heng, 2018). Recent work (Kunnas et al., 2024), which used an anti-biased, antiracist (ABAR) framework to examine how FSL teachers defined culture, reflected on the link between language and culture, and the role of students’ cultures in the FSL classroom, showed that while teachers increasingly held more socially-oriented views on culture, there is a strong need to develop critical orientations in ICTL teacher preparation. This aligns with more recent literature in ICTL which advocates for a more intentional accounting of power relations in the process of intercultural communication (Guilherme, 2022), and even infusing advocacy work that supports social and political action when developing IC (Ladegaard & Phipps, 2020), as a way of responding to teachers’ mandates of preparing the critical thinking skills among the youth of tomorrow.

FSL teachers equipped to teach in the 21st century must balance teaching about culture, with culture and through cultural artefacts and activities. Specifically, implementing culture in the classroom should “require us to reach beyond the paradigms which are sustained by intercultural discourse” (Phipps, 2010, p. 5) and not reinforce a policy of liberal multiculturalism (Kubota, 2004). Liberal multiculturalism, in which diversity and culture are addressed as a form of political correctness, provides little substance in terms of cultural knowledge. Instead, interactions with cultures are often limited to “celebrating” diversity and place an over-extended focus on commonalities or differences (exoticizing and essentializing the Other) between cultures. Worse, liberal multiculturalism paves the way for colour-evasiveness among language professionals (e.g., claiming to treat all students the same, or limiting inclusive practice to promoting tolerance as a virtue), which ends up denying or silencing racial (and other social) realities for students, and obscuring issues of power and privilege.

Recommendations

Teacher education programs need to promote cultural proficiency as much as language proficiency for L+ teachers. That is, L+ teachers must be able to engage with culture as an object of study in respectful ways, and they must be able to navigate (and teach how to navigate) intercultural communication. For teachers to understand their role as social agents of language and culture, they need more robust hands-on experiences to understand who they are as bi-/plurilinguals in Canada, as members of the francophonie in general and/or as French speakers and teachers. While having teacher candidates participate in a teaching abroad experience can help improve their intercultural competence (Bournot-Trites et al., 2018), this recommendation might be a classist luxury that is not available to many teacher candidates who do not have the time or funds to travel abroad. Opportunities to develop as cultural beings should be embedded more concretely into preparation programs through open critical discussions about French cultures and intentional identity work on their cultural identities. One way to do this is through the use of art-based activities (Masson & Côté, under review). Specific examples of activities are available for teacher educators at the L2 ART website (https://sites.google.com/view/l2-art/accueil-home). With these experiences, language teachers could better understand their cultural identities, French cultures, their interactions, and how to engage students culturally.

Developing intercultural competence also extends beyond knowledge about and interaction with French cultures to include the interaction of French language classrooms within their local communities. For instance, teacher education programs can explore the following with teachers: What is the local history of French communities in this context? What are other language groups in this area? How do these cultures come into contact? What does it mean to be teaching a colonial language in my context? What forms of privilege or oppression have local communities experienced, and how might this inform our interactions? Such questions can lay the foundation for developing a critical approach to teaching French that is essential to establishing culturally adapted and responsive teaching practices. Indeed, FSL preparation programs do not always address culture in their programs in ways that respectfully acknowledge the local realities of teaching French, a colonial language, in a settler colonial context and may, in fact, reproduce oppressive and discriminatory ideas and practices (Masson et al., 2022). For FSL teachers, it is therefore essential to consider what it means to be working and learning in a settler colonial context, and more specifically, what challenges it presents to following mandates for promoting equity and inclusion in the language curriculum. FSL teachers need intercultural competence to work with colleagues and students who may be from the post-colonial diaspora (i.e., those who have emigrated from former colonies), part of Indigenous communities, or part of the settler-colonial community which continues to settle this land and impose its cultural dominance (see Wernicke, Calla & George, under review, for an example of how one teacher preparation program addresses this with their candidates). Developing critical perspectives that recognize the power relations between different groups on this territory is an integral part of applying intercultural competence for Canadian FSL teachers, what we have also termed critical intercultural competence (Kunnas et al., 2024; Masson et al., 2022).

Vital to the success of preparing FSL teachers to teach in culturally adapted and responsive ways, which is increasingly becoming the norm across school boards and ministries of education, includes preparing teachers to engage with intercultural competencies and knowledge based on the principles of antiracist and anti-oppressive education; to critically assess materials they choose to work with and mandated materials, and; to ground themselves in strong professional identities that draw from their own and their students’ cultures.

Pedagogical Knowledge and Skill

Pedagogical knowledge has been defined as the “knowledge, theories and beliefs about the act of teaching and the process of learning” (Gatbonton, 2008, p. 162). These categories form the knowledge base that is key for teachers’ success. In L+ education, researchers emphasize the unique positioning of L+ teachers’ pedagogical knowledge (Salvatori & MacFarlane, 2009; Faez, 2011). In our definition of pedagogical knowledge and skills for FSL teachers, we include general pedagogical knowledge, subject-specific knowledge (knowledge about the French language) and subject-specific pedagogical knowledge (knowledge about how to teach French as an L+). FSL teaching is unique in that the content of the course (the French language) is also often the medium of communication in class. Yet, additional “language teachers typically enter the profession with largely unarticulated, yet deeply ingrained, notions about what language is, how it is learned, and how it should be taught” (Johnson, 2009, pp. 13-14).

Because teachers’ knowledge base determines how they operationalize theories of learning in their teaching practice, a process known as praxis (Freire, 1970), the concept of identity-as-pedagogy (Morgan, 2004) is crucial for understanding how FSL teachers develop their pedagogical knowledge and skill. It operates at the intersection of how they embody pedagogy in their classrooms, how they understand language as a construct and how they position themselves toward language learning and teaching. At this core, self-efficacy is an important component in developing the pedagogical knowledge and skills pillar. A well-developed sense of self-efficacy translates into confidence in the teacher’s teaching philosophy (Bigelow & Ranney, 2004).

Alongside the need for FSL teachers to develop their linguistic identity (Pillar 1) and their cultural identity (Pillar 2), they must develop their pedagogical identity (Pillar 3) to truly be able to position themselves with confidence and intentionality in their practice. However, pedagogical knowledge and modes of transmission do not exist in a vacuum. As Lynch & Motha (2023) have shown, understandings of identity and knowledge can reproduce colonial ways of thinking and viewing the world, and these will have an impact on teacher identity formation. Critical pedagogy (Freire, 1970) states that developing critical consciousness among future teachers is essential for promoting social justice and equity (Chan & Coney, 2020). This is particularly true in FSL programs where there is a great need to trouble the reproduction of standards of Whiteness, oppressive pedagogical practices, and colonial ways of thinking (Grant et al., under review; Kunnas, 2023; Masson et al., 2022).

With increasingly rapidly changing professional contexts, FSL teachers need greater support to prepare for 21st-century teaching. Specifically, FSL teachers need greater preparation in terms of developing anti-biased, anti-racist practices (Masson et al., 2022; Kunnas, 2023), gender and queer inclusive practices (Grant, 2022), using digital technology (Boreland et al., 2022), and, working with multilingual learners (Mady et al., 2017). Add to this, that official policy documents meant to support teachers, such as curricula, can also reproduce oppressive ideologies and be limited in the ways that they support FSL teachers to challenge dominant discourses of what is ‘normal’ (Carroll et al., 2024; Grant et al., 2024).

Recommendations

For FSL teachers of the 21st century, integrating and adapting content that is relevant to current issues (such as addressing social justice, reconciliation with Indigenous communities, environmental preservation, developing critical media literacy and digital literacy) means that teachers must be better equipped to modify their lessons to better meet the real-world needs of their students. For FSL teacher educators, the challenge is to bridge general and language-specific pedagogical knowledge. For instance, while action-oriented or neurolinguistic approaches are valuable tools for learning how to teach language, these also must be anchored to broader general pedagogical approaches, specifically those that promote equity and inclusion, such as universal design for learning and culturally responsive teaching. A commonly reported challenge facing FSL teachers is the lack of French resources in schools, often forcing teachers to spend hours translating English resources (ACPI, 2018), or the lack of awareness about where to find and how to adapt resources (Wernicke et al., 2022; Culligan et al., 2023). To support them, teacher candidates should be introduced to pedagogical currents such as multimodal/critical literacy education, culturally responsive teaching, project-based learning, and the like. The commonality across these pedagogical currents is that they place teacher autonomy and critical reflection at their core, and thus, for teacher educators, this can be a means to encourage self-efficacy among future teachers. Some of these have been explored in FSL contexts to great success, demonstrating how FSL teachers enact pedagogical efficacy and creativity in ways that support social justice and equity in their classrooms (Lau et al., 2017; Masson, 2021; Sabatier et al., 2013).

In our practice, we also witnessed a lack of ability to find, evaluate, and adapt French resources in the context of teacher education. French resources that reflect the professional needs of teachers and the learning needs of students are crucial to promoting self-efficacy and, in turn, affect FSL teachers’ identity development. One example of developing 21st-century professionalism among FSL educators has been led by the group called FSLdisrupt (www.FSLdisrupt.org) which sought to find French-language books that respond to culturally responsive teaching and learning needs in the high school FSL classroom to develop FSL students’ critical literacy. In collaboration with a teacher education program, this professional learning community has been developing skills, materials, and resources to re-orient its practice to include critical literacy in FSL.

Collaborative Professionalism

Collaborative professionalism is an intentional, ongoing form of collaboration which requires teachers to engage meaningfully with other professionals. This is distinct from professional collaboration, which can be understood as teachers working together in any capacity. Collaborative professionalism involves teachers’ commitment to being ongoing learners who are willing to be vulnerable with colleagues. The end goal of collaborative professionalism is to improve student learning and success (Hargreaves & O’Connor, 2018). Collaborative professionalism is important for fostering teachers’ sense of belonging to the school community as “teachers in collaborative cultures realize there are others who can help and support them” (p. 2). Through collaborative professionalism, teachers engage in reflective activities and problem-solving, which helps them overcome challenges, such as feelings of isolation and devaluation of their subject matter.

Like the other pillars, a strong sense of self-efficacy is essential for successful collaborative professionalism. For FSL teachers teaching in primarily anglophone school contexts, FSL teachers can experience low self-efficacy, limiting their abilities to form positive professional relationships with their non-FSL colleagues and leading them to feel overworked and isolated in their L+ teaching practice (Knouzi & Mady, 2014; Masson, 2018). This barrier to collaboration limits FSL teachers’ ability to succeed by making them feel unsupported and unsatisfied, which could, in turn, lead them to leave the profession. Fundamental to the notion of collaborative professionalism is the idea of building a shared vision with colleagues (e.g., on how to teach French) to foster collective efficacy and collective autonomy, as well as build networks of accountability and support among the community of teachers.

Recommendations

This pillar promotes the stance of teachers as lifelong learners. It challenges the myth that FSL teachers should be completely prepared as professionals by the end of their teacher education program (CASLT, 2022). By encouraging collaborative professionalism between FSL teachers specifically, their development as professionals becomes a collective experience that provides them with opportunities to challenge their own standpoint and grow as teaching professionals. For teacher education programs often characterized by neoliberal policies, the logic of professional learning communities has the potential to become altered among future FSL teachers, such that it loses its fundamental value and long-term benefits (Kaszuba et al., 2024, in press). Hence, developing FSL teachers’ collaborative professionalism must be intentional.

By making collaborative professionalism a cornerstone of teacher education programs, associate teachers, teacher candidates, professors, and practicing teachers can work together synergistically before, during and after they enter the profession. Professors in the program can model forms of collaborative professionalism; teacher candidates can be encouraged to practice collaborative professionalism with their colleagues, mentors and professors (see www.readyFSL.ca for examples of how to apply collaborative professionalism within teacher education programs). However, for such changes to take root, teacher education programs must make structural changes that will support teacher educators in investing time and energy into developing equitable professional learning communities. This would mean making time for full-time and part-time professors to meet and collaborate with each other, and with seconded and associate teachers affiliated with the FSL teacher education program. In a study funded by the Ministry of Education in Ontario that implemented the Four Pillars for Success in two faculties of education, participants reported that they needed more time and training to understand and apply the principles of collaborative professionalism, such as mutual respect, allowing space for discussion/debate, feeling comfortable, being open, and learning from each other and with each other. They also reported that they could develop their language proficiency, intercultural competence, and pedagogical knowledge through collaborative professionalism in learning communities (www.readyFSL.ca).

Not only would an orientation towards fostering collaborative professionalism promote future FSL teachers’ sense of self-efficacy, but it would also lay the groundwork for their burgeoning leadership skills and the creative professional risk-taking necessary to enhance FSL programs throughout their careers. Consequently, teacher candidates would enter the profession with strong levels of self-efficacy and establish collaborative networks with colleagues, which is key to maintaining their sense of identity as teachers and lifelong learners.

Discussion

Fundamental conceptualizations about language and language learning are at the core of transitioning language ITE towards more equitable and re/humanizing approaches (Lyle, 2022) to teacher preparation that considers the whole learner. As such, in this paper, we seek to encourage language teacher educators to challenge ideas of language proficiency, the francophonie and intercultural competence rooted in reified notions of what language is and how it works, the connection between language teaching methodologies and inclusive teaching practices, and the potential for collaborative professionalism to create a safety net for future FSL teachers.

Although we offer a model to enhance FSL teacher retention starting in teacher education, teacher preparation is only one aspect of teachers’ professional lives. As the leaky pipeline continues while teachers enter the profession (Masson, 2018), it is important to recognize broader influences on L+ teacher attrition (Parks, 2017). Schaefer et al. (2012) distinguished between individual and contextual factors leading to attrition. Individual factors include teacher demographics, resilience, and any personal factors, such as family-related restraints. Teachers’ salaries, available support, and professional development are viewed as contextual factors. Nevertheless, Borman and Dowling’s (2008) meta-analysis revealed that working conditions are the most prominent predictor of teacher attrition. As a result, we cannot place the onus of remaining in the profession solely on teachers’ shoulders and need to look at broader systemic issues at play across schools and school boards (CASLT, 2022; Masson et al., 2019; Wernicke et al., 2022).

Once they enter the classroom, other social and political factors will influence teachers’ sense of self, belonging and identity development. For example, systemic influences can undermine FSL teachers’ professional sense of self once they are working (Masson, 2018). Teacher preparation programs are also under pressure from institutional expectations and systemic forces (Masson et al., 2022; Smith et al., 2023). This calls for more research on systemic issues through concerted collaborative efforts with school boards, ministries, officials, superintendents and principals to address retention issues to ensure that the systemic forces at play do not erode FSL teachers’ sense of self and well-being over time. There is a need for research with these same shareholders for ways of building up FSL teachers and maintaining their professional identities so that they can thrive and contribute to building strong FSL programs throughout their careers. Preparing FSL teachers by instilling strong professional identities can begin to address challenges and exclusionary practices that are part of broader systemic issues.

Concluding Thoughts

FSL teacher attrition is threatening the future of FSL programs in Canada. Professionalization, which was identified as one of the key factors in reducing FSL teacher attrition, can begin during teacher education. In this article, we offered the Four Pillars for Success model as a means to critically evaluate common practices in teacher education programs and support teachers in developing a stronger sense of professionalization. Offering tools and experiences that will help teachers navigate the complexities of the FSL teaching practice, can allow teachers more time to develop the level of agency and autonomy needed to mitigate persistent barriers and challenges throughout their careers.

The roles teachers play in the classroom are inextricably tied to their professional selves, their professional knowledge, and the context in which they operate. How we understand knowledge and who holds the privilege of generating, disseminating, questioning, and critiquing it, will reveal critical understanding of the roles and responsibilities of teachers within their sphere of sovereignty. Ultimately, with teacher education programs designed to foster agency among teachers to contribute to their own knowledge base, FSL teachers will create a more nuanced, complete view of educational environments and experiences, leading to more meaningful teaching and learning of FSL in schools and more satisfaction among teachers towards their profession.

References

Association Canadienne des professionnels de l’Immersion (ACPI). (2018). Final Report, Canada Wide Consultations. https://www.acpi.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Vol40_n1_Printemps_2018_final_en_web.pdf

Bayliss, D., & Vignola, M-J. (2007). Training non-native second language teachers: The case of anglophone FSL teacher candidates. Canadian Modern Language Review, 63(3), 371-398. http://dx.doi.org/10.3138/K2U7-H14L-5471-61W0

Biesta, G. (2007). Why “what works” won’t work: Evidence‐based practice and the democratic deficit in educational research. Educational Theory, 57(1), 1-22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-5446.2006.00241.x

Bigelow, M., & Ranney, S. (2004). Pre-service ESL teachers’ knowledge about language and its transfer to lesson planning. In N. Bartels (Ed.), Applied Linguistics and Language Teacher Education (pp. 179-200). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-2954-3_11

Boreland, T., Lotherington, H., Tomin, B., & Thumlert, K. (2022). The use of digital tools in French as a second language teacher education in Ontario. TESL Canada Journal, 39(2), 1-37. http://dx.doi.org/10.18806/tesl.v39.i2/1375

Borman, G., & Dowling, N. (2008). Teacher retention and attrition: A meta-analytic and narrative review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 78(3), 367–409. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308321455

Bournot-Trites, M., Zappa-Hollman, S., & Spiliotopoulos, V. (2018). Foreign language teachers’ intercultural competence and legitimacy during an international teaching experience. Study Abroad Research in Second Language Acquisition and International Education, 3(2), 275-309. http://dx.doi.org/10.1075/sar.16022.bou

Byrd Clark, J. (2008). So why do you want to teach French? Representations of multilingualism and language investment through a reflexive critical sociolinguistic ethnography. Ethnography and Education, 3(1), 1-16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17457820801899017

Byrd Clark, J., & Roy, S. (2022). Becoming “multilingual” professional French language teachers in transnational and contemporary times: Toward transdisciplinary approaches. Canadian Modern Language Review, 78(3), 249-270. http://dx.doi.org/10.3138/cmlr-2020-0023

Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence. Multilingual Matters. http://dx.doi.org/10.21832/9781800410251

Canadian Parents for French (2020). French as a second language enrolment statistics: 2015-2016 to 2019-2020. https://cpf.ca/en/research-and-advocacy/research/enrolment-trends/

Canagarajah, A. S. (2013). Interrogating the “native speaker fallacy”: Non-linguistic roots, non-pedagogical results. In G. Braine (Ed.), Non-native educators in English language teaching (pp. 77-92). Routledge.

Carroll, S., Masson, M., Grant, R., & Keunne, E. (2024). It's (in)escapable: Navigating a second language curriculum and its language in a settler colonial context. [Manuscript submitted for publication]

CASLT (2022). FSL teacher education project: Identifying requirements and gaps in French as a second language (FSL) teacher education: Recommendations and guidelines. https://www.caslt.org/en/research-and-project/fsl-teacher-education-project/

Chan, E., & Coney, L. (2020). Moving TESOL forward: Increasing educators’ critical consciousness through a racial lens. TESOL Journal, 11(4), e550. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/tesj.550

Cochran-Smith, M., & Keefe, E. S. (2022). Strong equity: Repositioning teacher education for social change. Teachers College Record, 124(3), 9-41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/01614681221087304

Cooke, S., & Faez, F. (2018). Self-efficacy beliefs of novice French as a second language teachers: A case study of Ontario teachers. Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 21(2), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.7202/1057963ar

Culligan, K., Battistuzzi, A., Wernicke, M., & Masson, M. (2023). Teaching French as a second language in Canada: Convergence points of language, professional knowledge, and mentorship from teacher preparation through the beginning years. Canadian Modern Language Review, 79(4), 352-370. http://dx.doi.org/10.3138/cmlr-2022-0059

De Neve, D., & Devos, G. (2017). Psychological states and working conditions buffer beginning teachers’ intention to leave the job. European Journal of Teacher Education, 40(1), 6–27. http://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2016.1246530

Faez, F. (2011). Developing the knowledge base of ESL and FSL teachers for K-12 programs in Canada. Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 14(1), 29-49.

Fairley, M. (2020). Conceptualizing language teacher education centered on language teacher identity development: A competencies‐based approach and practical applications. TESOL Quarterly, 54(4), 1037-1064. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/tesq.568

Freeman, D., & Johnson, K. (1998). Reconceptualizing the knowledge‐base of language teacher education. TESOL Quarterly, 32(3), 397-417. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3588114

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Herder & Herder.

Gatbonton, E. (2008). Looking beyond teachers’ classroom behaviour: Novice and experienced ESL teachers’ pedagogical knowledge. Language Teaching Research, 12(2), 161–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168807086286

Grant, R. (2022). Eyes wide open: Navigating queer-inclusive teaching practices in the language classroom for pre-service teachers. In M. Masson, H. Elsherief & S. Adatia (Eds.), Every teacher is a language teacher: Social justice and equity through language education (pp. 7-22). University of Ottawa Second Language Education Cohort. http://dx.doi.org/10.20381/ehd3-2t16

Grant, R., Masson, M., & Carroll, S. (2024). Unravelling the silence around gender and sexuality in a second language curriculum. [Manuscript submitted for publication]

Guilherme, M. (2022). From critical cultural awareness to intercultural responsibility: Language, culture, and citizenship. In T. McConachy, I. Golubeva, & M. Wagner (Eds.), Intercultural learning in language education and beyond: Evolving concepts, perspectives, and practices (pp. 101-117). Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781800412613-013

Hargreaves, A., & O'Connor, M. (2018). Collaborative professionalism: When teaching together means learning for all. Corwin Press.

Hofman, R., & Dijkstra, B. (2010). Effective teacher professionalization in networks?. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(4), 1031-1040. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.10.046

Ingersoll, R. (1997). Teacher professionalization and teacher commitment: a multilevel analysis, SASS. Department of Education Office of Educational Research & Improvement.

Ingersoll R., May H., & Collins G. (2019). Recruitment, employment, retention and the minority teacher shortage. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 27, 37. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.27.3714

Johnson, K. E. (2009). Second language teacher education: A sociocultural perspective. Routledge.

Kaszuba, A., Masson, M., Arnott, S., Grant, R., & Friesen, B. (in press). Negotiating policies and standards: a case study into discourses of accountability in Canadian Teacher Education. In J. Mena, R. Kane & C. J. Craig (Eds.), Inclusive trajectories and practices: ethical ideals tested by evidence (pp. tbd). Brill Sense.

Kayi-Aydar, H. (2015). Multiple identities, negotiations, and agency across time and space: A narrative inquiry of a foreign language teacher candidate. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies, 12(2), 137-160. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15427587.2015.1032076

Keating Marshall, K., & Bokhorst‐Heng, W. (2018). “I wouldn't want to impose!” Intercultural mediation in French immersion. Foreign Language Annals, 51(2), 290-312. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/flan.12340

Knouzi, I. & Mady, C. (2014). Voices of resilience from the bottom rungs: The stories of three elementary core French teachers in Ontario. Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 60(1), 62-80. http://dx.doi.org/10.55016/ojs/ajer.v60i1.55764

Kubota, R. (2004). Critical multiculturalism and second language education. In B. Norton & K. Toohey (Eds.), Critical pedagogies and language learning (pp. 30-52). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9781139524834.003

Kunnas, M. (2023). Who Is Immersion for? A Critical Analysis of French Immersion Policies. Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 26(1), 46-68. http://dx.doi.org/10.37213/cjal.2023.32817

Kunnas M., Masson, M., & Carroll, S. (2024). Critical conceptualizations of culture: Perspectives from additional language teachers. [Manuscript submitted for publication]

Ladegaard, H., & Phipps, A. (2020) Intercultural research and social activism. Language and Intercultural Communication, 20(2), 67-80. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2020.1729786

Lapkin, S., MacFarlane, A., & Vandergrift, L. (2006). Teaching French in Canada: FSL teachers’ perspectives. Canadian Federation of Teachers.

Lapkin, S., Swain, M., & Shapson, S. (1990). French Immersion research agenda for the 90s. Canadian Modern Language Review, 46(4), 638–674. http://dx.doi.org/10.3138/cmlr.46.4.638

Lasky, S. (2005). A sociocultural approach to understanding teacher identity, agency and professional vulnerability in a context of secondary school reform. Teaching and Teacher Education, 21(8), 899-916. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2005.06.003

Lau, S. M. C., Juby-Smith, B., & Desbiens, I. (2017). Translanguaging for transgressive praxis: Promoting critical literacy in a multiage bilingual classroom. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies, 14(1), 99-127. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15427587.2016.1242371

Le Bouthillier, J., & Kristmanson, P. (2023). Becoming a French second language teacher: Supporting confidence and competence. Second Language Teacher Education, 2(1), 21-42. http://dx.doi.org/10.1558/slte.24011

Lyle, E. (2022). Re/humanizing education (Lyle, Ed.). Brill. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/9789004507593

Lynch, R., & Motha, S. (2023). Epistemological entanglements: Decolonizing understandings of identity and knowledge in English language teaching. International Journal of Educational, 118, 102118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2022.102118

Macfarlane, A. & Hart, D. (2002). Shortages of French as a second language teachers: Views of school districts, faculties of education and ministries of education. Canadian Parents for French.

Madibbo, A. (2021). Blackness and la Francophonie: Anti-black racism, linguicism and the construction and negotiation of multiple minority identities. Presses de l'Université Laval. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv23khnb5

Madigan, D. J., & Kim, L. E. (2021). Towards an understanding of teacher attrition: A meta-analysis of burnout, job satisfaction, and teachers’ intentions to quit. Teaching and Teacher Education, 105, 103425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103425

Mady, C., Arnett, K., & Muilenburg, L. Y. (2017). French second-language teacher candidates’ positions towards allophone students and implications for inclusion. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 21(1), 103-116. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2016.1184330

Marx, S., Lavigne, A. L., Braden, S., Hawkman, A., Andersen, J., Gailey, S., Geddes, G., Jones, I., Si, S., & Washburn, K. (2023). “I didn’t quit. The system quit me.” Examining why teachers of color leave teaching. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 1-24. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2023.2218113

Masson, M. (2018). Reframing FSL teacher learning: Small stories of (re) professionalization and identity formation. Journal of Belonging, Identity, Language, and Diversity, 2(2), 77-102.

Masson, M., & Azan, A. (2021). Second language teacher attrition, retention and recruitment: issues, challenges and strategies for French as a second language teachers. Canadian Association of Second Language Teachers. https://www.caslt.org/en/product/teacher-attrition-lit-review/

Masson, M., Battistuzzi, A., & Bastien, M.-P. (2021). Preparing for L2 and FSL teaching: A literature review on essential components of effective Teacher Education for language teachers. Canadian Association of Second Language Teachers. https://www.caslt.org/en/product/effective-teacher-ed-lit-review/

Masson, M., Kunnas, M., Boreland, T., & Prasad, G. (2022). Developing an anti-bias, anti-racist stance: addressing colonial patterns of thought and practices in second language teacher education programs. Canadian Modern Language Review, 78(4), 385-414. https://doi.org/10.3138/cmlr.2021-0100

Masson, M., & Côté, S. (2024). Belonging and legitimacy for French language teachers: A visual analysis of raciolinguistic discourses. In X. Huo & C. Smith (Eds.), Interrogating Race and Racism in Postsecondary Language Classrooms (pp. 116-149). IGI Global. http://dx.doi.org/10.4018/978-1-6684-9029-7.ch006

Masson, M. & Côté, S. (2024). An arts-based multiliteracies approach to elicit meaning-making in language teacher identity work. [Manuscript submitted for publication]

Masson, M., Larson, E., Desgroseilliers, P., Carr, W., & Lapkin, S. (2019). Accessing opportunity: A study on challenges in French-as-a-second-language education teacher supply and demand in Canada. Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages. www.clo-ocol.gc.ca/en/publications/studies/2019/accessing-opportunity-fsl

Mason, S. (2017). Foreign language teacher attrition and retention research: A meta-analysis. NECTFL Review, 80, 47-68. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1253534

Morgan, B. (2004). Teacher identity as pedagogy: Towards a field-internal conceptualisation in bilingual and second language education. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 7(2-3), 172-188. http://dx.doi.org/10.21832/9781853597565-005

Norton, B. (2013). Identity and language learning. Multilingual Matters. http://dx.doi.org/10.21832/9781783090563

Parks, P. (2017). Understanding the connections between second language teacher identity, efficacy, and attrition: a critical review of recent literature. Journal of Belonging, Identity, Language, and Diversity, 1(1), 75-91.

Phipps, A. (2010). Training and intercultural education: the danger in ‘good citizenship’. In M. Guilherme, E. Glaser, & M. del Carmen Mendez-Garcia (Eds.), The Intercultural dynamics of multicultural working (pp. 59-77). Multilingual Matters. http://dx.doi.org/10.21832/9781847692870-007

Pillay, T. (2018). Visible minority teachers in Canada: Decolonizing the knowledges of Euro-American hegemony through feminist epistemologies and ontologies. In D. Wallin, & J. Wallace (Eds.), Transforming conversations: Feminism and education in Canada since 1970 (pp. 210-226). McGill-Queen’s University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/9780773554313-010

Ramjattan, V. (2019). Racist nativist microaggressions and the professional resistance of racialized English language teachers in Toronto. Race Ethnicity and Education, 22(3), 374-390. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2017.1377171

Richards, J., C. (2016). Teacher identity in second language teacher education. In G. Barkhuizen (Ed.), Reflections on language teacher identity research (pp. 193-144). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315643465-26

Riches, C., & Parks, P. (2021). Navigating linguistic identities: ESL teaching contexts in Quebec. TESL Canada Journal, 38(1), 28-48. http://dx.doi.org/10.18806/tesl.v38i1.1367

Roskvist, A., Harvey, S., Corder, D., & Stacey, K. (2014). ‘To improve language, you have to mix’: teachers' perceptions of language learning in an overseas immersion environment. Language Learning Journal, 42(3), 321-333. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2013.785582

Ruest, C. et Wernicke, M. (2021). Une perspective interculturelle pour une identité professionnelle positive des enseignant·e·s d'immersion. Journal de l'immersion, 43(2), 13-14.

Sabatier, C., Moore, D., & Dagenais, D. (2013). Espaces urbains, compétences littératiées multimodales, identités citoyennes en immersion française au Canada. Glottopol, 21, 138-161.

Salvatori, M. & MacFarlane, A. (2009). Profile and pathways: Supports for developing FSL Teachers’ pedagogical, linguistic, and cultural competencies. Canadian Association of Second Language Teachers.

Schaefer, L., Long, J., & Clandinin, D. (2012). Questioning the research on early career teacher attrition and retention. Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 58, 106–121. http://dx.doi.org/10.55016/ojs/ajer.v58i1.55559

Smith, C., Masson, M., Spiliotopoulos, V., & Kristmanson, P. (2023). A course or a pathway? Addressing French as a second language teacher recruitment and retention in Canadian BEd programs. Canadian Journal of Education, 46(2), 412-440. http://dx.doi.org/10.53967/cje-rce.5515

Sorensen, L. & Ladd, H. (2020). The hidden costs of teacher turnover. AERA Open, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858420905812

Swain, M., & Deters, P. (2007). “New” mainstream SLA theory: Expanded and enriched. Modern Language Journal, 91(s1), 820-836. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2007.00671.x

Tang, M., & Fedoration, S. (2022, November 3). The contradiction that is an L+ teacher: A guide to help me thrive. Congrès de l’ACPI.

Tang, M., Forte, M., & Côté, I. (2023). «ARKK! Mes élèves parlent en anglais!»: réflexions sur trois parcours professionnels et personnels. Cahiers franco-canadiens de l'Ouest, 35(1-2), 268-298. http://dx.doi.org/10.7202/1107484ar

Teng, F. (2019). Autonomy, agency, and identity in teaching and learning English as a foreign language. Springer. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-0728-7

Varghese, M. (2016). Language teacher educator identity and language teacher identity: Towards a social justice perspective. In G. Barkhuizen (Ed.), Reflections on Language Teacher Identity research (pp. 51-56). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315643465-11

Wernicke, M. (2017). Navigating native-speaker ideologies as FSL teacher. Canadian Modern Language Review, 73(2), 208-236. http://dx.doi.org/10.3138/cmlr.2951

Wernicke, M. (2020). Orientations to French language varieties among Western Canadian French-as-a-Second-Language teachers. Critical Multilingualism Studies, 8(1), 165-190.

Wernicke, M. (2022). “I’m Trilingual–So What?”: Official French/English Bilingualism, Race, and French Language Teachers’ Linguistic Identities in Canada. Canadian Modern Language Review, 78(4), 344-362. https://doi.org/10.3138/cmlr-2021-0074

Wernicke, M. (2023). L’insécurité linguistique dans l’enseignement du français langue seconde : de quoi parle-t-on ? Cahier de l’ILOB, 13, 199-222.

Wernicke, M., Calla, C., & George, N. (under review). Rethinking French-as-a-Second-Language (FSL) education as a space for supporting Indigenous language work on Musqueam Land. [Manuscript submitted for publication]

Wernicke, M., Masson, M., Arnott, S., Le Bouthillier, J., & Kristmanson, P. (2022). La rétention d’enseignantes et d’enseignants de français langue seconde au Canada: au-delà d’une stratégie de recrutement. Éducation et francophonie, 50(2). https://doi.org/10.7202/1097033ar

Wernicke, M., Masson, M., Adatia, S., & Kunnas, M. (in press). A critical examination of race in French second language research. In R. Kubota & S. Motha (Eds.), Race, Racism, and Antiracism in Language Education (pp. tbd). Routledge.

Xu, Y. (2016). Becoming a researcher: A journey of inquiry. In G. Barkhuizen (Ed.), Reflections on language teacher identity research (pp. 120-125). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315643465-23

[1] We use “FSL” to refer to French as a “second language” programs in this paper as this is common nomenclature in Canada, in part due to French being one of the two official languages of Canada, however, we note the limitations of this terminology (Tang & Fedoration, 2022). To move past any kind of discourse that reinforces a hierarchy of languages we will refer to “additional language” (L+) teacher preparation throughout the paper.

[2] We wish to stress that we are not suggesting that future FSL teachers should not be provided with support to work on their language proficiency. Simply that many of the current approaches in place in teacher education programs are deficit-based.