Teacher Recruitment and Retention in Select First Nations Schools

Robin Mueller and Sheila Carr-Stewart

University of Saskatchewan

Larry Steeves and Jim Marshall

University of Regina

The school improvement movement, widely embraced by educational practitioners both nationally and internationally, has featured an embedded emphasis on assessment of meaningful student learning and academic achievement (Purinton, 2011; Harris, 2003). Ongoing research toward better understanding student learning has revealed that there are persistent academic achievement gaps for some groups of students (Fullan, 2005; Blankstein, 2004), and in 2000 and 2004, the Auditor General also noted this educational achievement gap between First Nations and non-First Nations students. Historically, First Nations students have experienced significantly lower levels of educational achievement and attainment than non-First Nations students (White, Maxim, & Spence, 2004; Wotherspoon, 2006). Systemic issues which affect student achievement must be addressed in order to improve the educational processes and maximize educational outcomes for Aboriginal people (Helin, 2006; Poelzer, 2009). Teacher recruitment and retention, closely connected with teacher efficacy, are considered as causal factors that influence the quality of student learning and educational achievement. Teacher recruitment and retention are critical factors affecting the delivery of quality educational services in rural and remote areas including reserve schools.

Though research in support of claims regarding explicit teacher retention—student achievement link is not substantive, teacher retention has been identified as a key determinant of student learning outcomes. Issues pertaining to teacher recruitment and retention have become pressing for educational policy makers in recent years. Typically, concerns about attracting and retaining teachers have been associated with economic matters of supply and demand; it is considered necessary to maintain an adequate flow of teachers into expanding and diversifying systems of education (BTEC, 2007; McDonald, 2001; Wayne, 2000). Teacher recruitment and retention, however, is a multi-faceted, complex issue, and educational administrators in a variety of contexts, including First Nations schools, struggle to attract and keep teachers for myriad reasons.

The purpose of this paper is to investigate teacher recruitment and retention in select First Nations schools in Saskatchewan with particular focus on compensation—teacher salaries and benefits. The analyses presented here with respect to underlying structures and practices that lead to teacher attrition in First Nation schools must be tempered by acknowledgement and discussion of those schools which were performing well in terms of teacher retention practices. Of the schools participating in our research, two of the seven exhibited relatively low teacher attrition over a 4-year period and exhibited signs of educational stability across several areas. In one of these schools, the average teacher salary was the highest of all the schools under study, and leave and benefits arrangements, while not quite meeting Saskatchewan provincial norms, were both provided for and consistent across most domains. The other school demonstrating reasonable and consistent teacher retention rates was among the closest to provincial grids with respect to salary, sick leave, pension, life insurance, and health and dental benefits. In this school, teacher compensation packages were reported to have been consistent over many years, and respondents that provided data for the researchers indicated that the First Nation school was committed to achieving educational stability. Both successful schools exhibited a significant level of local board control of education and managed their schools similar to schools within other educational jurisdictions.

Context

Prior to consideration of our study into the salient teacher recruitment and retention issues in select First Nation schools, it is essential to understand the broader context informed by historical factors in the delivery of Western education services for and within First Nations communities. Since the arrival of newcomers, the delivery of Western education services for First Nations students has been a matter of both concern and ongoing conflict (Charters-Voght, 1999). The British North America Act of 1867 (see Creighton, 1970) created two separate education systems in Canada: (a) provincial authority for education within their boundaries, and (b) federal jurisdiction for First Nations education. In 1876, the federal government enacted the Indian Act which outlined Canada’s administrative responsibilities for First Nation education. Constitutionally, First Nations were excluded from developing and delivering educational policy and practice for their own people (White & Peters, 2009). This formal and legal exclusion resulted in the development of distinctly European, ethnocentric education systems for First Nations people that “reflected the European linguistic and religious beliefs of the settlers” (Carr-Stewart, 2011, p. 75). Residential and missionary schools became the standard model for educating and assimilating First Nations students (White & Peters, 2009): Such colonial initiatives constituted “dramatic failures in policy” that precipitated significant challenges (Steeves, 2009, p. 22).

Indian Control of Indian Education

Only in the last quarter of the 20th century did First Nations people regain input into their children’s education (Barman, Hebert, & McCaskill, 1986; Battiste & Barman, 1995). The catalyst for change and the transferring of administrative responsibility for education from the federal government to First Nations was the National Indian Brotherhood’s (NIB) Indian Control of Indian Education (1972). The latter document was a statement of First Nation educational philosophy and values. It was submitted to the Government of Canada in response to the federal government’s, 1969 White Paper which proposed the repeal of the Indian Act and treaties agreed to between the Crown and First Nations, and the transfer of services for First Nations people from the federal government to provincial governments (White & Peters, 2009). The Indian Control of Indian Education document affirmed “the right of First Nations people to educate their own children” (Charters-Voght, 1999, p. 69). The NIB document was adopted in principle by the federal government which undertook to transfer school management responsibilities to First Nations. This was accomplished within existing budgets, policies, and federal guidelines. Today, First Nations in Saskatchewan administer education programs and schools at the local level and have developed educational governance and organizational structures in support of such activity. Tribal Councils within the province deliver, to varying degrees, second level educational services, such as special education. Funding arrangements between Canada and First Nations are usually for the duration of 1- to 3-year agreements. The financial levels and services to be provided are established by federal funding formulas and for the last decade have been tied to volume increase (in students) and a 2% price increase. Funding transfers, from the federal government through the Department of Indian Affairs to First Nations who manage educational services on Canada’s behalf, have not addressed the historical disparity in teacher salaries between teachers employed in provincial schools and those employed in schools located on reserves. Furthermore, lack of or limited pension and benefits funding, due to limited federal transfers, continues to detract from employment in First Nations schools.

Research Context and Objectives

This study was part of a broader study previously initiated for the purpose of examining relationships between second level funding and improved student learning in First Nations schools. An unanticipated outcome emerged from the first study when interviewees and focus group participants indicated that critical issues associated with teacher recruitment and retention had largely been ignored. Furthermore, participants in the initial study indicated that teacher attrition had a persistently negative impact on educational outcomes for Aboriginal students in their community-administered schools. Our research objectives were to explore and to better understand the teacher recruitment and retention in First Nations schools. The research agenda grew to include an aim to explore issues of teacher recruitment and retention and associated impacts on student achievement.

Research Method

Descriptive evidence was collected that allowed researchers to accurately characterize current conditions regarding the factors contributing to teacher attrition/retention in our sample of First Nations schools. Documentary material was solicited from seven First Nations administered schools in Saskatchewan, including documents reflecting teacher recruitment methods, teacher qualifications, staff turn-over rates, salary levels, contract arrangements, leave provisions, benefits, and professional development provisions. In the process of data collection, the researchers also corresponded verbally with school administrators in order to elicit pertinent contextual details with respect to the documentary items. It should be noted that the schools were of varying sizes and employed anywhere between two and 21 teachers each.

Literature Review: Teacher Retention, Teaching Efficacy, and Student Achievement

A vigorous history of research with respect to teacher recruitment, retention, and attrition does much to inform our current inquiry. Attrition in the teaching profession has been “viewed as an impediment to the educational, social, cultural and economic goals of schools and communities” (Macdonald, 1999, p. 841). High rates of teacher attrition precede increases in system spending on teacher recruitment and training, as well as significant administrative human resource time (Ghere & York-Barr, 2007; Kukla-Acevedo, 2009). A well-established research tradition in education has brought to bear many general studies that have focused on determining why teachers are attracted to, and stay at, schools, as well as isolating school and community factors that contribute to teacher retention and attrition. Researchers have long speculated about determinants of teacher turn-over, including: (a) teacher characteristics such as sex, age, ethnicity, cumulative education, experience, level of preparation, stage of career, job satisfaction, personal health, and marital status; (b) school characteristics such as location, community conditions, student/teacher ratio, class sizes, pay structure, compensation offered, availability of mentorship opportunities, and public or private status; and (c) student characteristics such as socio-economic class, individual behavioural issues, level of academic advantage, level of parental support, living conditions, attitudes toward school, and family responsibilities (Guarino, Satibanez, Daley, & Brewer, 2004; Ingersoll, 2001; Kukla-Acevedo, 2009; Macdonald, 1999; Stinebrickner, 1998). Organizational determinants of teacher attrition have also been demonstrated, including workplace conditions such as behavioural climate, administrative support to teachers, and amount of teacher input in decision making (Ingersoll, 2001; Kukla-Acevedo, 2009). However, it is only recently that educational researchers have begun to speculate about relationships between teacher effectiveness, retention at particular schools, and associated educational outcomes for students.

Studies have indicated substantial variance in student achievement outcomes that correlate with differences among teachers, confirming that teacher effects on student achievement are significant (Nye, Konstantopoulos, & Hedges, 2004). In any given year, “students are deflected upward or downward from their expected growth trajectory by virtue of the classrooms to which they are assigned” (Rowan, Correnti, & Miller, 2002). Further, when students are subject to ineffective teaching year after year, they demonstrate significantly lower achievement gains than those students assigned to effective teachers in subsequent years (Darling-Hammond, 2000). Effective teaching, then, clearly influences student learning and over-all quality of educational outcomes.

Several widely assumed variables, or characteristics, of effective teaching have been investigated, among them cumulative years of teaching experience. Studies have indicated a relationship between increased years of service and parallel increases in teacher effectiveness (Brown, Molfese, & Molfese, 2010; Darling-Hammond, 2000; Nye et al., 2004). It is widely accepted that teachers with less than 5 years experience are typically less effective than those with 5 or more years experience (Croninger, King Rice, Rathbun, & Nishio, 2007; Darling-Hammond, 2000). Some of the most compelling evidence with respect to teacher experience indicates dramatic increases in pupils’ reading comprehension when students are paired with more experienced teachers (Croninger et al., 2007; Rockoff, 2004). Additionally, longitudinal evidence suggests that, if schools focus on recruiting and retaining experienced teachers, they could expect substantial increases in student achievement (Greenwald, Hedges, & Laine, 1996).

Teacher quality is positively correlated with student learning outcomes, and teacher experience is linked to teacher quality. If schools are subject to high rates of teacher attrition, particularly among those who are less experienced, a likely consequence for the school will result: cohorts of perpetually inexperienced teachers. This in turn increases likelihood that students will be subjected to less effective teaching in more than one school year, thus compromising the quality of long-term student achievement. Maximizing efforts to recruit teachers and maintain experienced ensures not only appropriate staffing of a professional workforce, but contributes to the maintenance of high quality educational outcomes.

Challenges to Teacher Retention in First Nations Schools

In Saskatchewan, recruiting and retaining teaching professionals in First Nations schools has been identified as uniquely challenging due to contextual features manifest in these particular settings (McDonald, 2001; McNinch, 1994; Monk, 2007; Wotherspoon, 2006). Several parallel issues constitute implicit indicators, including a lack of teacher experience and appropriate training (Monk, 2007), inconsistencies in hiring practices (McNinch, 1994; Monk, 2007), lack of job security and comprehensive benefits packages (McNinch, 1994; Monk, 2007), teacher isolation and transition difficulties within the context of rural communities (Collins, 1999). Furthermore, cultural, linguistic, and social factors may be faced by new teachers in rural and remote areas (Monk, 2007). According to Monk (2007), in rural schools (many First Nations schools would be classified as rural schools) “working conditions are problematic, student needs are great, support services are limited, and professional support networks are inadequate” (p. 167).

Definitive links between teacher retention and student achievement outcomes in First Nations schools have not yet been demonstrated in published research. However, it is reasonable to assume that teacher attrition from these schools, as in other schools, has a negative effect on student achievement. The most compelling piece of evidence regarding this link has emerged from studies of teacher effectiveness, which has been positively correlated with increases in student achievement regardless of school effectiveness levels (Chell, Steeves, & Sackney, 2009; Rowe, 2007). Teachers represent the component of public education that is closest to the student; in other words, teachers have more direct impact on student experience than any one other school-bound factor (Brucato, 2005; Rowe, 2007). Some researchers have suggested that the teacher is more central to student achievement outcomes than external family and community influences (Darling-Hammond, 2000). Turn-over of teachers from school year to school year, and sometimes during the year, has significant impact on students. In a study focussed on special education, Ghere and York-Barr (2007) argued that students experience considerable losses due to teacher attrition; students are the educational stakeholders who are most profoundly influenced by disruptions in program continuity and the severed relationships with caring adults caused by teacher departure.

An association between duration of teacher appointments (retention rates) and teacher effectiveness has, to date, also not been demonstrated in relevant research. However, it is difficult to imagine such effectiveness being achieved without teachers being retained in schools for a significant enough time to develop positive relationships and establish trust within the school community. Trust is a relational dynamic developed over time as stakeholders grow to understand, commit to, and maintain the obligations and expectations inherent in their respective roles (Bryk & Schneider, 2003). Trust is an essential component of effective teaching and positive educational relationships “cannot be established and maintained without a strong bond of trust existing between teacher and pupils” (Troman, 2003, p. 172). A trusting relationship between student and teacher enables the student to take appropriate risks and engage creatively in classroom learning, with a likely consequence of enhanced student achievement (Troman, 2003). In fact, “Without trust, people divert their energies into self-protection and away from learning” (Mitchell & Sackney, 2000, p. 49). Trust has been identified as a key component of positive and progressive school cultures that engender maximum student learning (Brucato, 2005; Busher, 2006).

In addition to dynamics of trust experienced between students and teachers, trust also informs schools as workplace cultures. Teachers feel most satisfied and professionally involved in school cultures of collegiality and collaboration (Ma & MacMillan, 1999; Weiss, 1999); such cultures are influenced in large part by teacher attitudes (Brucato, 2005). When teacher attrition occurs, “there are indirect costs during the transition period that affect the workload, morale and productivity of the remaining employees” (Ghere & York-Barr, 2007, p. 22). Dynamics of functional workplace teams are disrupted when teachers leave, leading to increased opportunity for miscommunication and strained working relationships among remaining staff (Ghere & York-Barr, 2007). Additionally, when teachers leave a school, they take all the implicit cultural and organizational knowledge they have gained with them (Busher, 2006; Ghere & York-Barr, 2007), and destroy any pedagogic partnerships previously established with other teachers (Williams, Prestage, & Bedward, 2001). This aspect of teacher departure is perhaps the most difficult and time-consuming to resolve, as it encompasses the many developmental, collegial and professionally productive relationships formed in schools (Williams et al., 2001) that are undone when attrition occurs (Ghere & York-Barr, 2007). In combination with aspects of student achievement and trust already noted, consideration of this aspect of workplace culture affected by teacher attrition suggests that retaining teachers is a highly desirable outcome for all schools.

Research Results

The following tables and discussion reflect data collected from seven First Nations schools with respect to a variety of factors including teacher attrition rates, salaries, contract terms, and benefits arrangements. While school administrators were generally cooperative in providing documentation there are still several notable gaps throughout the data. Comprehensiveness of data collected from each school depended on what was available to educational administrators. For the most part, the gaps in documentation or statistical information reflect differing systems of educational governance across nations, rather than issues of accessibility.

Teacher Turnover in the First Nations Schools

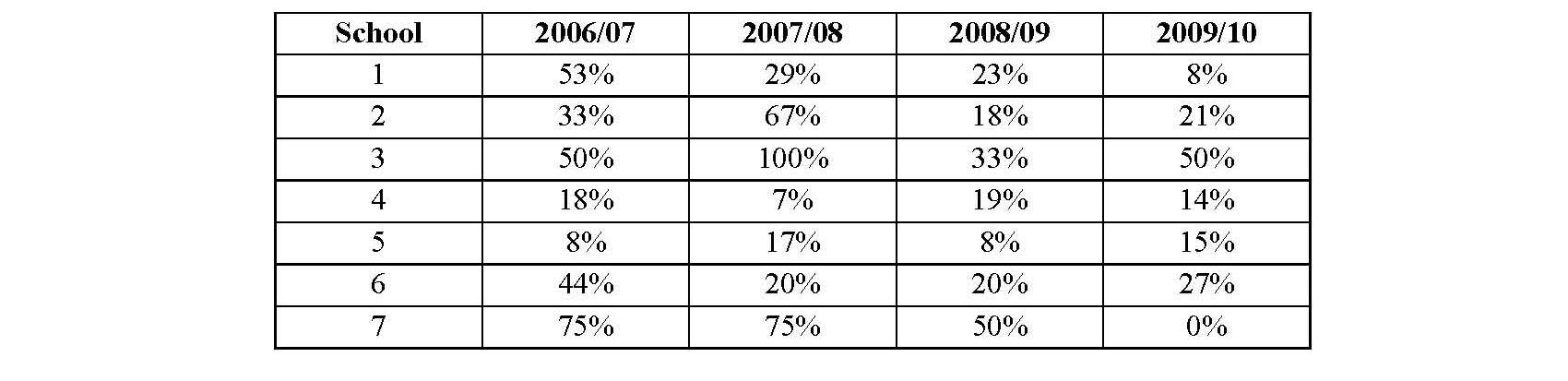

The participating schools collected teacher turn-over data for the 4-year period between 2006 and 2010. Long term attrition trends, then, were not discernible, but the researchers were able to assess a “snapshot” of current conditions (see Table 1). While it appears that teacher retention rates have improved for these schools over the past four years, regardless of schools size and staff complement (varies from two to 21 teachers), attrition averages are still in excess of what would be considered average teacher turn-over resulting from retirement and/or illness within Saskatchewan provincial schools.

Table 1

Percentages of Teacher Turn-over in Selected Schools, 2006 to 2010

Teacher Salary, Contract, and Benefits

Anecdotal evidence has historically pointed toward a variety of factors that contribute to teacher attrition from First Nations schools, some of which include differential teacher salaries, ad hoc salary agreements, limited teaching term agreements, inadequate or non-existent benefits packages, lack of identified vacation time, and limited sick leave time. The researchers collected data with respect to these potential retention factors and compared results to Saskatchewan provincial standards (see Table 2).

Table 2

Teacher Salary, Contract, and Benefits Summary (Provincial Data from Saskatchewan Teacher’s Federation, n.d.)

Salary and contract data indicated little consistency across schools. Some schools used provincial standards as guidelines, especially in consideration of salary baselines; however, many of new teacher salaries were determined on an ad hoc basis and results were largely dependent on the teacher’s knowledge of provincial norms and his or her ability to negotiate with the principal and/or educational authority upon hiring. Administrators in schools where teacher salaries were approaching equivalency to provincial standards expressed concern that salaries might change dependent upon the allocation of educational funds by the funding agency—the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada. Uncertain salary negotiations were further exacerbated by short term contract agreements, generally 10 to 12 months in duration. If teachers were rehired in subsequent years, they had to renegotiate compensation packages. Some educational administrators reported transparent procedures with respect to the rehiring process, while stakeholders in other schools reported that hiring was highly politicized and reflective of the respective political climate and hiring processes and decisions were not transparent.

Inconsistencies across First Nations schools were more evident with respect to teacher benefits. Some First Nations articulated employment agreements for all band staff, and educators were considered within those frameworks. Consequently, if the majority of staff voted to eliminate benefits (for example), teachers were included in that decision. None of the schools met provincial standards for sick leave or pension contributions, and health and dental benefits packages for teachers sometimes lagged behind provincial norms. Most schools reported that funding for sick time, leaves, pensions, and benefits was unpredictable; some reported that funds allocated for these benefits were exhausted or were significantly depleted. Benefits offered to teachers were often changed or withdrawn with little or no notice due to changes or lack of consistent educational program budgets from the Department of Indian Affairs.

Educational Policy

First Nations schools exist within an educational policy vacuum created by the lack of federal educational policy and tenuous “control” of administering schools on behalf of the federal government. The Auditor General (2000) noted that the Department of Indian Affairs “needs to identify the nature of leadership it must take to ensure that its authorities, responsibilities and obligations for education are met” (p. 4-11) and needs to “articulate and formalize its role in education” (p. 4-10). Furthermore, the Auditor General recognized that the “situation is complex and urgent….[and] [a]lthough the Department has chosen to rely on First Nations and the provinces for the design and delivery of appropriate education, the Department acknowledges that this approach does not diminish its responsibility and accountability” (p. 4-5). The lack of policy clarity at the federal level has major effects on First Nations education authorities and schools. Schools in this study reported confusion associated with existing policy and the mechanisms for policy-related decision making. Policy ambiguity was exacerbated by financial ambiguity, as most educational funding was part of flexible funding arrangements that led to high fluidity and occasional unpredictability when the Nations were faced with emergencies.

Analysis

Administrators at most of the First Nations schools involved in our research associated issues pertaining to teacher attrition with a negative impact on their schools. There is enough variation among the data collected, to suggest that factors contributing to teacher attrition are largely contextual and influenced by deficits at both the federal and local levels of educational governance structures. Short term agreements (1 to 3 years) between the Department of Indian Affairs and individual First Nations have led to unpredictable salary negotiations, uncertain term agreements, and benefits packages that are significantly different from provincial norms, all of which contribute to teacher attrition in First Nations schools. Teachers considering employment in either provincial or First Nation schools would find the compensation packages within the provincial system more favourable than those provided by First Nations schools. Substantial research suggests that increases in salary and benefits are positively associated with enhanced ability to recruit good teachers (Guarino et al., 2004). Higher rates of compensation can be seen as symbolic of the esteem with which a school views its teachers, and teachers will consequently conduct active comparisons between salary and benefits offered by each entity (Rebore & Walmsley, 2010). Further, the insecurity of 1-year term agreements is typically viewed as an unattractive feature of employment; job insecurity has detrimental consequences for employee attitudes, job satisfaction, personal heath, and employee commitment to the organizations of employment (De Witte, 1999; Sverke, Hellgren, & Näswall, 2002).

The differential salary and benefits agreements noted in individual First Nations schools indicate broader inconsistencies, namely lack of an educational “system” among First Nations. While provincial systems of education exhibit definitive flaws, the system’s strengths are associated with predictive value. In other words, the provincial system allows for transparency in policy articulation, ease of maintaining accountability for the achievement of common educational goals, use of mechanisms to balance state and local control of education, and predictability and stability with respect to allocation of resources to education (McEwen, 1995). While such predictability may be equated with pedantry and bureaucracy for some, the benefits of implementing province-wide systems of education are clear with respect to teacher retention outcomes: Salaries are determined based on a well-established salary grid; benefits packages are not only high in quality but consistent across the entire system; and, teachers are represented by a provincial teachers organization in order to ensure accountability.

A comprehensive education system was not devolved from the federal level to First Nations; rather, individual schools or authorities were funded to manage or administer schools on behalf of the government of Canada. The lack of an educational structure has led to changing ad hoc structures at the First Nations level. Uncertain structures have led to a lack of transparency and little consistency with respect to educational structures and practices across First Nations schools.

Research demonstrates that improvements in educational process and student learning outcomes for First Nations students appear to occur most readily in schools that implement their own education structures and focus on strategies for integration of Indigenous voice within established structural constraints (Barnhardt & Kawagley, 2005; Bell, 2004; Power & Roberts, 1999). Such strategies are founded on a range of local governance models and are undergirded by maintenance of local control within a common, well established governance structure. (Bell, 2004)

Limitations and Items for Further Study

The results and analysis presented here are representative of the first step of the first phase of inquiry in a larger, comprehensive research agenda designed to better understand dynamics informing teacher recruitment and retention in First Nations schools. This first step was largely quantitative, and results represent a “snapshot” view of seven schools within a limited period of time. Results cannot be broadly generalized, and we do not suggest that the data reported here is representative of other First Nations schools. The next phase of research will contribute to our attempt to generate more broadly applicable results; the research will provide not only detailed quantitative data from a comparative provincial school division, but also rich qualitative data to provide a nuanced and contextual view of the way teacher retention and attrition is experienced by key stakeholders within the reserve schools we studied.

Conclusion

The research for this study was situated within one Tribal Council and involved eight schools with differing student enrolments. Similarly, teacher employment in these schools varied between two and 21 teachers. As indicated in Table 1, while teacher attrition has improved somewhat over the 4- year period of this study, teacher attrition remains a significant issue. Our research revealed that regardless of school staff complement, teacher salaries and benefit packages are differential across First Nations schools, and while these differences are in part reflective of priorities at the individual community, the major factor influencing teacher salaries and benefits is the level of funding received from the federal government for the administration and operation of schools for the provision of educational services. Limited or uncertain education budgets in First Nations schools affect not only the level of salary and benefits teachers receive but also student services, curriculum development and adaptation, and professional development (Macdonald, 1999; Ghere & York-Barr, 2007). Furthermore, the attrition of individual teachers has negative implications for student achievement, parental involvement, and the implementation of educational goals (Ingersoll, 2001; Kukla-Acevedo, 2009; Macdonald, 1999). The quality of First Nations education is further eroded by lack of legal recognition and an appropriate and consistently funded system of education as well as an educational policy vacuum. We hypothesize that such factors have a predominantly negative impact on First Nations school efficacy, and in turn, on student achievement.

The research discussed here represents a foundational step in the exploration of factors influencing teacher recruitment and retention in select First Nations schools. A robust research tradition has already detailed the dynamics of teacher attrition, generally, and we aim to augment this research by generating a more meaningful understanding of such dynamics in context of First Nations education, particularly with respect to the effect teacher attrition has on student achievement in context of First Nations communities.

References

Auditor General of Canada (2000, April). Indian and Northern Affairs Canada—Elementary and secondary education. In Report of the Auditor General of Canada (Chapter 4). Ottawa, ON: Office of the Auditor General of Canada.

Auditor General of Canada (2004, November). Indian and Northern Affairs Canada—Education program and post secondary student support. In Report of the Auditor General of Canada to the House of Commons (Chapter 5). Ottawa, ON: Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada.

Barman, J., Hébert, Y., & McCaskill, D. (1986). The legacy of the past: An overview. In J. Barman, Y. Hébert, & D. McCaskill (Eds), Indian education in Canada (pp. 1-22). Vancouver, BC, Canada: University of British Columbia Press.

Barnhardt, R., & Kawagley, A. O. (2005). Indigenous knowledge systems and Alaska native ways of knowing. Anthropology and Education Quarterly, 36(1), 8-23. Retrieved from http://proquest.umi.com.cyber.usask.ca/pqdlink?index=5&did=840796381&Src...

Battiste, M., & Barman, J. (Eds)(1995). First nations education in Canada: The circle unfolds. Vancouver, BC, Canada: University of British Columbia Press.

Bell, D. (2004). Sharing our success: Ten case studies in Aboriginal schooling. Kelowna, BC, Canada: Society for the Advancement of Excellence in Education. Retrieved from http://dspace.hil.unb.ca:8080/xmlui/bitstream/handle/1882/8733/SOS2004.p...

Blankstein, A. M. (2004). Failure is not an option: Six principles that guide student achievement in high-performing schools. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Board of Teacher Education and Certification (BTEC) (2007). Educator supply and demand in Saskatchewan to 2011. Regina, SK: Saskatchewan Learning.

Brown, E. T., Molfese, V. J., & Molfese, P. (2010). Preschool student learning in literacy and mathematics: Impact of teacher experience, qualifications, and beliefs on an at-risk sample. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk, 13(1), 106-126. doi: 10.1080/10824660701860474

Brucato, J. M. (2005). Creating a learning environment. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Education.

Bryk, A. S., & Schneider, B. (2003). Trust in schools: A core resource for school reform. Educational Leadership, 60 (6), 40-45. Retrieved from http://web.ebscohost.com.cyber.usask.ca/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=2&...

Busher,

H. (2006). Understanding

educational leadership: People, power and culture.

Maidenhead, Berkshire, UK: Open University Press.

Carr-Stewart, S. (2011). First Nations education: A constitutional and treaty right. In M. Prytula, & D. Burgess (Eds), Legal and institutional contexts of education (7th ed., pp. 75-78). Saskatoon, SK, Canada: University of Saskatchewan.

Castellano, M. B., Davis, L., & Lahache, L. (Eds). (2000). Aboriginal Education: Fulfilling the Promise. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

Charters-Voght, C. (1999). Indian control of Indian education: The path of the Upper Nicola Band. Canadian Journal of Native Education, 23(1), 64-99. Retrieved from http://proquest.umi.com.cyber.usask.ca/pqdweb?RQT=305&SQ=issn%280710%2D1...

Chell, J., Steeves, L., & Sackney, L. (2009). Community and within-school influences that interrelate with student achievement: A review of the literature. In L. Steeves (Ed.), Improving student achievement: A literature review (A Report for the Saskatchewan Ministry of Education, pp. 5-38). Regina, SK: Saskatchewan Instructional Development & Research Unit (SIDRU).

Collins, T. (1999). Attracting and retaining teachers in rural areas. ERIC Digest: Clearinghouse on Rural Education and Small Schools. Retrieved from http://www.ericdigests.org/2000-4/rural.htm

Creighton, D. (1970). Canada's first century. Toronto, ON: Macmillan of Canada.

Croninger, R. G., King Rice, J., Rathbun, A., & Nishio, M. (2007). Teacher qualifications and early learning: Effects of certification, degree, and experience on first-grade student achievement. Economics of Education Review, 26, 312-324. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2005.05.008

Darling-Hammond, L. (2000). Teacher quality and student achievement: A review of state policy evidence. Journal of Education Policy Analysis, 8(1) 1-44. Retrieved from http://epaa.asu.edu/ojs/article/viewFile/392/515

De Witte, H. (1999). Job insecurity and psychological well-being: Review of the literature and exploration of some unresolved issues. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 8(2), 155-177. doi: 10.1080/135943299398302

Fullan, M. (2005). Fundamental change. New York: Springer.

Harris, A. (2003). Effective leadership for school improvement. London: Routledge Falmer Ghere, G., & York-Barr, J. (2007). Paraprofessional turnover and retention in inclusive programs: Hidden costs and promising practices. Remedial and Special Education, 28(1), 21-32. doi: 10.1177/07419325070280010301

Greenwald, R., Hedges, L. V., & Laine, R. D. (1996). The effect of school resources on student achievement. Review of Educational Research, 66(3), 361-396. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1170528

Guarino, C., Santibanez, L., Daley, G., & Brewer, D. (2004, May). A review of the research literature on teacher recruitment and retention (Technical Report, Education Commission of the States). Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation. Retrieved from http://wwwcgi.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/2005/RAND_TR164.pdf

Helin, C. (2006). Dances with dependency. Woodland Hills, CA: Ravencrest Publishing.

Ingersoll, R. M. (2001). Teacher turnover and teacher shortages: An organizational analysis. American Educational Research Journal, 38(3), 499-534. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3202489

Kukla-Acevedo, S. (2009). Leavers, movers, and stayers: The role of workplace conditions in teacher mobility decisions. The Journal of Educational Research, 102(6), 443-452. Retrieved from http://proquest.umi.com.cyber.usask.ca/pqdlink?index=1&did=1741692771&Sr...

Ma, X., & MacMillan, R. B. (1999). Influences of workplace conditions on teachers’ job satisfaction. The Journal of Educational Research, 93(1), 39-47. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/27542245

Macdonald, D. (1999). Teacher attrition: A review of literature. Teaching and Teacher Education,15(8), pp. 835-848.

McDonald, D. (2001). Teacher recruitment in Northern Saskatchewan (Unpublished master’s thesis). University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK.

McEwen, N. (1995). Introduction: Accountability in education in Canada. Canadian Journal of Education, 20(1), 1-17. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1495048

McNinch, J. (1994). The recruitment and retention of Aboriginal teachers in Saskatchewan schools. Regina, SK: Saskatchewan School Trustees Association. Retrieved from http://www.saskschoolboards.ca/old/ResearchAndDevelopment/ResearchReport...

Mitchell,

C., & Sackney, L. (2000). Profound

improvement: Building capacity for a learning

community.

Lisse, Netherlands: Swets & Zeitlinger.

Monk, D. H. (2007). Recruiting and retaining high-quality teachers in rural areas. The Future of Children, 17(1), 155-174. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4150024 Society for the Advancement of Excellence in Education (2005, February). Moving forward in aboriginal education: Proceedings of a national policy roundtable. Kelowna, BC: Society for the Advancement of Excellence in Education.

Nye, B., Konstantopoulos, S., & Hedges, L. (2004). How large are teacher effects? Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 26(3), 237-257. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3699577

Poelzer, G. (2009). Education: A critical foundation for a sustainable north. In F. Abele, T. J. Courchene, F. L. Seidle, & F. St. Itilaire (Eds), Northern exposure: Peoples, powers and prospects in Canada’s north (pp. 427-465). Montreal, QC, Canada: Institute for Research on Public Policy.

Power, K., & Roberts, D. (1999). Successful early childhood indigenous leadership. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Research in Early Childhood Education. Canberra, Australia. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/PDFS/ED459027.pdf

Purinton, T. (2011). Six degrees of school improvement: Empowering a new profession of teaching. Charlotte, NV: Information Age.

Rebore, R. W., & Walmsley, A. L. E. (2010). Recruiting and retaining Generation Y teachers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Rockoff, J. E. (2004). The impact of individual teachers on student achievement: Evidence from panel data. The American Economic Review, 94(2), 247-252. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3592891

Rowan, B., Correnti, R., & Miller, R. J. (2002). What large-scale, survey research tells us about teacher effects on student achievement: Insights from the Prospects student of elementary schools. Teachers College Record, 104(8), 1525-1567. Retrieved from http://www.tcrecord.org.cyber.usask.ca/library/Issue.asp?volyear=2002&nu...

Rowe, K. (2007). School and teacher effectiveness: Implications of findings from evidence-based research on teaching and teacher quality. In T. Townsend (Ed.), International handbook of school effectiveness and improvement (pp. 767 - 786). Netherlands: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-5747-2

Saskatchewan Teacher’s Federation (n.d.). Benefits. Saskatchewan: Author. Retrieved from https://www.stf.sk.ca/portal.jsp?Sy3uQUnbK9L2RmSZs02CjV/LfyjbyjsxsF8TUlt...

Steeves, L. (Ed). (2009, February). Improving student learning: A study of the contribution of enhanced second-level services within the Yorkton Tribal Council in relation to the Saskatchewan Pre K–12 educational system. (A Report for the Yorkton Tribal Council). Regina, SK: Saskatchewan Instructional Development and Research Unit (SIDRU).

Stinebrickner, T. R. (1998). An empirical investigation of teacher attrition. Economics of Education Review, 17(2), pp. 127 – 136. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com.cyber.usask.ca/science?_ob=MImg&_imagekey=B...

Sverke, M., Hellgren, J., & Näswall, K. (2002). No security: A meta-analysis and review of job insecurity and its consequences. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 7(3), 242-264. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.7.3.242

Troman, G. (2003). Teacher stress in the low-trust society. In L. Kydd, L. Anderson, & W. Newton (Eds.), Leading people and teams in education. London: Paul Chapman Publishing.

Wayne, A. J. (2000). Teacher supply and demand: Surprises from primary research. Education Policy Analysis, 8(47). Retrieved from http://epaa.asu.edu/ojs/article/viewFile/438/561

Weiss, E. M. (1999). Perceived workplace conditions and first-year teachers’ morale, career choice commitment, and planned retention: A secondary analysis. Teaching and Teacher Education, 15, 861 – 879. doi:10.1016/S0742-051X(99)00040-2

White, J., Maxim, P., & Spence, N. D. (2004). An examination of educational success. In J. P. White, P. Maxim, & D. Beavon (Eds), Aboriginal policy research: Setting the agenda for change (Vol. 1, pp. 129-148). Toronto, ON, Canada: Thompson Educational Publishing.

White, J. P., & Peters, J. (2009). A short history of Aboriginal education in Canada. In J. P. White, J. Peters, D. Beavon, & N. Spence (Eds.), Aboriginal education: Current crisis and future alternatives (pp. 13–31). Toronto, ON: Thompson Educational Publishing.

White, J. P., Peters, J., & Beavon, D. (2009). Enhancing educational attainment for First Nations children. In J. P. White, J. Peters, D. Beavon, & N. Spence (Eds.), Aboriginal education: Current crisis and future alternatives (pp. 117-174). Toronto, ON: Thompson Educational Publishing.

Williams, A., Prestage, S., & Bedward, J. (2001). Individualism to collaboration: The significance of teacher culture to the induction of newly qualified teachers. Journal of Education for Teaching, 27(3), 253-267. doi: 10.1080/02607470120091588

Wotherspoon, T. (2006). Teachers’ work in Canadian aboriginal communities. Comparative Education Review, 50(4). Retrieved from http://courses.educ.queensu.ca/foci255/readings/documents/TeachersWorkin...