Note: The coloured rectangles show importance by size, in terms of how often this theme came up in conversation, with the smallest these (Spaces) indicating least important and the largest theme (Emotional) indicating most important.

Inclusive Classrooms: A Confessional Tale on a Métissage

Amanda Culver and Tim Hopper

University of Victoria

Authors’ Note

Amanda Culver https://orcid.org/0009-0001-8111-5955

Tim Hopper https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1347-5422

We have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Thanks to the participants in the métissage for your commitment to the ideals of inclusivity and support for this research experience. Thanks to Dr. Kathy Sanford and Nabila Kazmi for volunteering to be the voices for the reading of the métissage.

The video included in the article as critical context to explain the confessional tale. The complete métissage as a video is found at: https://youtu.be/H6xznYyqahs (Culver & Hopper, 2023).

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Amanda Culver. Email: amandaculver@uvic.ca

An Extract

From Métissage “Queering Inclusive Spaces”

Authenticity

Inclusion feels like being able to express things the way that is right to me.

(Reader #1)

Questions are encouraged.

Participation is encouraged,

but not forced (or leveraged for marks). (Reader #2)

Hard topics are addressed with care

Not shied away from.

(Reader #3)

It’s an ability to apologize and recognize that someone may have made an error in their words and behaviours. A cultural humility in understanding people can be wrong, including self.

Apologies are not forced.

I can identify my child’s contributions to the classroom community

Positive AND constructive feedback is shared.

My experience with and knowledge of my child is honoured.

Inclusion is people-focused, not business-focused

We teach students first, not curriculum.

We are not empty vessels, waiting to be filled.

We are whole. We are complete.

We are writing this confessional tale on our experience of conducting a métissage research process as an assignment within a course as part of a graduate program. Amanda Culver, is a queer elementary school teacher pursuing a PhD research program on the 2SLGBTQIA+ community within local classrooms and schools, and Tim Hopper, their instructor in a graduate level research methods course, supported them in exploring the métissage process. Together they co-created a confessional tale, unpacking the tensions, opportunities, and challenges in developing a métissage project. They queered the métissage process by unpacking it to reveal the anxieties, tensions, and possibilities that occur as a novice researcher takes up the role of researcher whilst promoting a co-participant stance with their study participants. As such, this article develops a relativist standpoint of epistemology between researcher, friends, and an academic pursuing a degree (Sparkes, 2002). In this article, we offer insights from Amanda’s reflective comments interwoven with their critical friend, Tim’s, comments on both the métissage process and a commitment, through research and teaching practice, to create safer spaces for all to share and construct meanings and to change exclusionary and silencing practices.

Métissage is derived from the Canadian word Métis, and is a way of merging and blurring genres, texts, and identities, as well as a means for taking an active literary stance, a political strategy, and pedagogical praxis (Chambers et al., 2002). As an arts-based research methodology, a métissage is comprised of a series of narrative writings by single authors which are then interwoven together to create a larger thematic text or artifact with the intent of “transformation from the inside out” (Worley, 2006, p. 518). Essentially, a métissage is a collective autoethnography around a common phenomenon, with stories rooted in the participants’ past and in their stories of becoming. The scope of métissage will be outlined more fully within the confessional frame that will be explained next.

Confessional Tale

Confessional tale, as noted by Van Maanen (1988), is the postscript that follows the research progression in a highly personalized diary-like format. The intent of a confessional tale is to show how the work came into being and to reveal the dilemmas and tensions contained in the process (Hopper et al., 2008; Sparkes, 2002). Confessional is seen as a complimentary genre in relation to a particular research methodology, highlighting ethical and methodological issues that may conflict with the researchers’ values or with guidelines associated with the research process being undertaken. Essentially, this genre captures the reflexivity from dialectical conversations between the researcher, a critical friend, and the intent of the research project.

As noted by Sparkes (2002), confessional tales “reveal what actually happened in the research process” from start to finish (p. 58). They are highly personalized, as they are written from the perspective of the researcher. This genre captures the reflexivity from dialectical conversations between the researcher, a critical friend, and the intent of the research project. Mistakes and questions are given space to exist within the research process. “Confessional tales appeal to personalized author(ity) and emphasize the researcher’s point of view” (Sparkes, 2002, p. 59). Kluge (2001) noted that what is being represented in a confessional tale is the researcher’s personal account through the reflexive process of what they experienced in conducting the study.

The researchers share accounts from the beginning of the research process: insights on choosing the topic, framing the study, identifying a methodology, and recruiting participants. The researchers write accounts during the research process, with reflections on collecting and recording data, analyzing and interpreting data, and verifying the interpretations. Finally, they reflect about the end of the process: writing up of the findings, and in the case of arts-based approaches, the performance piece, and then sharing the findings with others. Sparkes and Smith (2014) wrote that confessional tales claim to research knowledge if they:

In confessional tales, the focus is on the interpretative process and the problems of coming to know rather than just the findings of the study, providing a degree of reflexivity concerning how the researchers might influence interpretations and conclusions. As Douglas and Carless (2010) stated, “Our use here of a confessional tale can be seen as a methodological strategy which seeks to align with epistemologies that promote the creation of reflexive knowledge” (p. 338). The confessional tale offers a hermeneutic process that raises ethical and methodological questions about how we come to know about ourselves and others via our research activities.

In this article, confessional tales are used to highlight some of the challenges and tensions faced within the process of choosing métissage as a research methodology (Hopper et al., 2008; Sparkes, 2002), particularly in the co-creation process and the need for the participants to maintain some type of confidentiality. The confessional pieces in this article raise questions for consideration for those intending to explore métissage as a research genre. The self-reflexive confessional material is interwoven in relation to the guidelines for doing the métissage research and its commitment to presenting a cultural critique. The intent in this confessional article is, therefore, for readers to examine their own practices and assumptions, while they are learning about the practices and assumptions of others engaged in a process they wish to engage in (Schultze, 2000, p. 8). Ultimately, as Sparkes and Smith (2014) noted, our goal is “helping … inquirers learn from the private mistakes of others, and removing the inhibitions generated when novice researchers are fed solely on a diet of completed, methodologically sanitised, successful research projects” (p. 158).

Inclusivity in BC Classrooms

The métissage study focused on inclusivity. It focused on marginalized groups who are excluded due to some form of disability, Indigenous background or being queer. Summarized below are key insights that frame some of the issues surrounding inclusivity in BC schools within these marginalized groups.

Sexual and Gender Diverse Students

Studies that focus on queer experiences in public schools, by queer people, are few and far between. We know that 62% of 2SLGBTQIA+ students feel unsafe at school (Peter et al., 2021). Indeed, as Amanda notes, “I have been that student. I hope that, throughout my career, my research will make it so that schools become safer places for me and my community.” This personal, lived experience motivated the métissage study. Everyone has a sexual orientation and gender identity. While sexual orientation was protected under the Canadian Human Rights Act in 1996, gender identity and expression was not added as a prohibited ground of discrimination under the BC Human Rights Code until July 2016. This code forced all BC school districts to include specific references to SOGI (Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity) in anti-bullying policies by the end of 2016 (Education and Child Care, 2017).

School districts have all drafted policies to protect and support 2SLGBTQIA+ students and staff. However, these policies were designed without analyzing the layered conditions that shape how schools give meaning to trans and non-binary gender. As Meyer and Keenan (2018) wrote, “Without that knowledge, existing policy, like existing law, has largely been created through a lens that frames static, cisgender identity as the norm, a lens that is further shaped by institutionalized assumptions about race, class, and ability” (p. 749). They also claimed that policies and practices aimed at “safety” and “inclusion” often seek to achieve these goals through the regulation of individual behavior, rather than changing the institutional conditions that produce normative systems of gender (p. 739). This cosmetic attempt to address 2SLGBTQIA+ issues does not address the root causes. As Herriot et al. (2018) noted, “Despite numerous legal precedents and policy changes across multiple jurisdictions, the lived realities of LGBTQ school students in British Columbia continue to be rife with harassment and a lack of safety” (p. 701). How then, in relation to 2SLGBTQIA+, do we make classrooms safer, more inclusive spaces?

In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada published its 94 Calls to Action to respond to the experiences and impact of the residential school system. Beyond 94 was launched by CBC News in 2018 to report on the status of the Calls to Action. Today, none of the seven education-specific Calls to Action have been completed (CBCNews, 2018). Call to Action 63 is stated as follows:

We call upon the Council of Ministers of Education Canada to maintain an annual commitment to Aboriginal education issues, including: (1) Developing and implementing Kindergarten to Grade 12 curriculum and learning resources on Aboriginal peoples in Canadian history, and the history and legacy of residential schools; (2) Sharing information and best practices on teaching curriculum related to residential schools and Aboriginal history; (3) Building student capacity for intercultural understanding, empathy and mutual respect; (4) Identifying teacher-training needs relating to the above. (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015)

Every year, the BC Ministry of Education publishes the “How Are We Doing?” Report, which monitors the performance of Indigenous students in the BC public school systems. In the 2021/22 school year, Indigenous students reported greater rates of being bullied, teased, or picked on at school than non-Indigenous students (First Nations Education Steering Committee, 2022). Clearly, work needs to be done so that Indigenous students can exist safely within the education system.

Inclusive classrooms need to be considered through a disability lens. During the Community Living Movement, which started in the 1950s, parents of children with developmental disabilities and people who had experienced institutionalization came together to fight for de-institutionalization and access to education in Canada (Inclusion BC, n.d.). The BC School Act was amended in 1959, making it a public responsibility to educate children with developmental disabilities (Inclusion BC, n.d.). Decades later, in 2006, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), which was the first legally binding international treaty which protected the rights of persons with disabilities. Canada signed the CRPD in 2007 (Inclusion Canada, n.d.). While Canada has made significant progress in making schools more inclusive, “segregated, special classrooms, limited access to teams, and lowered expectations are just some of the ways that children with an intellectual disability are excluded in Canadian schools” (Inclusion Canada, n.d., para. 4). For example, French Immersion students with suspected learning disabilities in Grade 1 often do not receive a formal evaluation until Grade 4, when they begin to receive instruction in English. Students with disabilities continue to face challenges concerning equitable access to education within Canada.

Policies are in place for BC classrooms, and all Canadian classrooms to be inclusive spaces for all, including for queer, Indigenous, and/or disabled students. Culver’s (2022) métissage study set out to offer personal insights on inclusive spaces for three participants who identify in these marginalized groups.

Confessional Asides on Research Process

In this section, we will explain the process followed to conduct the métissage. Amanda’s voice will be in italics, reporting on their reflexive voice as noted by both authors or using the first person “I” to capture Amanda’s hindsight and reflections. At times we will use “we” to capture the shared conversations on the research process between the researcher and their participants, as well as Tim. Confessional pieces are indented at .25” and direct quotes from the research study recordings are indented .5” and in quotation marks. We propose that switching from third person narration, to Amanda’s voice in first person and then to shared reflections as “we” provides more clarity for understanding the decisions made and considerations for future métissage work, creating a dialogical space in the research process. In the next three sections we will attempt to weave in the confessional insights in italic as we go through the three phases highlighted by Kluge (2001): the beginning, during, and write-up phases.

Literature on Métissage and Initial Confessional Reflections

Métissage comes from the Latin mixtus, meaning mixed. Importantly, the words “Métis” and “tissage” are front and center. “Tissage” is French for “weaving.” Métis people are those with both Indigenous and European ancestry, a woven embodiment of both the colonized and the colonizer. This indigeneity is central to the work of métissage, where life stories are woven together. “In a political sense, métissage resists grand narratives, or discourses that attempt to totalize experiences. Instead, the goal of ‘mixing’ or ‘braiding’ strands of life-writings is to highlight differences” (Cox et al., 2017, p. 43). For example, Lowan-Trudeau (2017) wove one strand (his Métis identity, living on reserve) with another (his European ancestry, living in the city) to examine his relations with place. Benson et al. (2020) included three voices woven together around three central questions, such as “Where do we come from?” The “knot” of their braid involved reflection on the métissage process. Additionally, Kovach (2018) explained that “Indigenous methodologies require exploration of identity, an ability to be vulnerable, a desire for restitution, and an opening to awakenings” (p. 388). As non-Indigenous co-authors, we are committed to these tenets throughout this decolonizing, reflexive methodology and hope that this comes across clearly in this article.

Our métissage study was created by Amanda as partial fulfillment for course requirements in a graduate level qualitative research methods course. The purpose of the mini study was for students to learn about different forms of qualitative research by exploring the different representation processes that could be used, often referred to as research genres (Hopper et al., 2008). Students wrote a weekly journal entry as they pursued a qualitative research project, reviewed exemplar research papers on a genre and then developed a mini study, with course-based ethics granted, drawing on the genre studied. During initial discussions with the course instructor (Tim), the students (including Amanda) explored the potential of a variety of genres such as autoethnography, confessional, and métissage to consider a phenomena of their choosing. Through dialogical responses to Amanda’s reflective comments, Tim suggested that Amanda focus on métissage as it seemed to capture their interest in working with others to explore the research phenomena of classroom inclusivity from a SOGI perspective. Amanda selected métissage because they were attracted to how it offered a space for multiple voices to share their lived experiences with inclusivity. Métissage is useful in this regard because it begins with a simple prompt and later gives space for participants to interact with each other, weave their insights together by building off each other’s stories, and making kin (Benson et al., 2020). The power of métissage, which flourished through this study, is summed up by Bishop et al. (2019):

The weaving is much like a braid. Three parts, individually shared, now woven together. The work of the individual becomes the weave of the collective. Once individual, now shared. Once individual, now community, once alone, now together. In coming together, the power of the collective becomes visible. (p. 14)

Benson et al. (2020, p. 40) claimed that conscientiously crafting personal stories deepens the understanding of the social conditions in which those experiences were rooted. They believed that métissage has transformational affordances for both authors and audience alike, which could be used to encourage educators (administrators, teachers, and others who work with children) to consider ways that their learning spaces can foster inclusivity and move towards decolonization.

In addition, métissage is useful in juxtapositioning the voice of the researcher as both observer and t as participant. Lowan-Trudeau (2017), for example, “explore[d] themes of diaspora and identity politics” (p. 510), through métissage, weaving Indigenous and Western perspectives in place to “[develop] many strategies to reclaim and to reimagine Indigeneity and community” (p. 519).

In my course paper (see Culver,2022) I take on two roles, as researcher with my participants, and then as co-participant sharing and unpacking in relation to what we the participants say about inclusivity, our own experiences. In this confessional piece I reflect with Tim on the research process, braiding the conventional academic format with one that is more personal, encouraging the reader to interpret this duality through their own lenses. I am nervous about blending these two roles together—researcher and participant—and wonder how to switch between these two roles in a way that does not compromise the research.

I admit, too, that I am nervous to embark on researching using this methodology as a non-Indigenous person. I am reminded of Kovach’s (2018) words: “It gets back to knowing the community and investing in that relationship.” I am absolutely invested in the relationship with our co-participants (who are also my dear friends) and am committed to finding ways to share this learning with others so that we can do right by the students in our classrooms.

Cox et al. (2017) claimed that métissage embodies critical pedagogy by shifting the power dynamic and affording internal transformation for all those involved. They also claimed that métissage fosters critical dialogue around individuals’ reflections, more effectively recognizes various subjectivities, and makes learning more visible (p. 53).

Looking back, I note that this was very apparent in the meetings surrounding the métissage: both during the pre-meeting where we determined the writing prompt and during the meeting where we shared and began to weave our stories together. By allowing historically marginalized voices to share their/our stories, uninterrupted, the White, heteronormative, colonial patriarchy became more evident. This is what decolonization can look like, both in research and in the classroom. Their voices highlight the power imbalance that exists within the public school system. Creating space to hear their stories makes learning more visible, which begins to shift that power dynamic for the benefit of all who work and exist within the education system.

Métissage Research Question and Participants

The initial research question was, “How do we make classrooms more inclusive, specifically through a SOGI lens?” Tim suggested that this seemed like an effective initial research question, but due to the short timeframe of the mini study and the need to work with a group in métissage, the limit of a SOGI lens may not be possible. However, initially this SOGI lens really was the focus for Amanda and was a key part of their motivation to do graduate work.

In the conservative, religious household I grew up in and in the publicly funded Catholic school I went to, the word “gay” was only ever used in a derogatory way. I didn’t know what being bisexual was until university, and the first time I heard the word “transgender” was in my second year of teaching, when I had a trans student in my class and wished I was more informed. Meanwhile, since as long as I can remember, I knew that my sexual orientation and gender identity did not fit within the cishet norms forced upon me, despite the lack of vocabulary. Whenever I asked questions, I was silenced. My Grade 10 religion teacher told me that “if you are lukewarm, God will spit you out.”

The message from school was loud and clear: if you aren’t cisgender or heterosexual, something is wrong with you. As a result, my mental health suffered, and I did not feel a sense of belonging at school. I truly believed something was wrong with me, which I largely attribute to school not being an inclusive, representative space. While I consider myself lucky to have gotten out alive, I recognize that isn’t always the case. I wish my school experience was better and I wish I was better prepared entering my own classroom. Which brings me to the research question: How do we make classrooms more inclusive, specifically through a SOGI lens?

This desire to focus on a SOGI question became hard to pursue within the assigned 3-week window for data collection of the course. Amanda, through encouragement in the course journal interactions with Tim, recognized they could approach acquaintances who represented other marginalized groups, so Amanda settled for the more generalized research question: “How do we make classrooms more inclusive?”

Working with the constraints of limited time and a limited pool of potential participants, I recognized that I would likely work with participants who did not identify as members of the queer community and, as such, felt that the question needed to be more open-ended. Unfortunately, most of the queer teachers I knew were on medical leaves due to the anti-queer hate they were experiencing. Similarly, racialized teachers were also leaving due to racism regularly faced in their workplaces. Considering these limitations, and with encouragement from Tim, I knew I would likely take on one of the participant roles to bring a queer voice to the research but was disappointed that no other queer voices would be included for this particular study.

Amanda, then, approached participants who shared experiences of marginalization, recognizing that inclusive practices expand beyond the queer community and, in the end, benefit everyone. Amanda also wanted to include participants who all had experiences in classrooms, but not necessarily as teachers.

Luckily, I am a part of a friend group who met through advocacy work and who have since stayed in touch. I wanted to select participants with whom I had a prior relationship as this would enable the previous sense of trust from sharing experiences and knowing each other’s motivations that allowed us to take on inclusivity, something we had all struggled with from different perspectives. Without this previous sense of connection, trust, and kinship it would have taken time to foster the pre-existing collegiality. This collegiality allowed us to dismantle, or at least reduce the hierarchy that is inherent in researcher-participant relationships. I wanted to create a space for marginalized voices to be heard and, personally, disrupt the power imbalances I perceived in researching with participants. With this friend group, we frequently discuss social justice issues and shared frustrations with the lack of representation in education. I knew that conversations about inclusive spaces would flow naturally with this group, but worried that their own work and personal schedules would not align with the timeline of this research. Thankfully, both friends agreed to participate.

Both participants had experienced classrooms as teachers. One participant is also a parent of a child with a disability. The other participant self-identifies as Indigenous. Amanda’s voice was included as a queer teacher’s perspective. Participants have asked that no further identifying information be shared beyond what is given here in order to preserve their requested anonymity. As co-authors, we recognize that identities are intersectional and that these participants bring a variety of perspectives to this research, both individually and as a group.

During the Research Process

Two group meetings were scheduled, as well as a third, optional, meeting. This was not what Amanda initially anticipated as other métissages, such as that of Bishop et al. (2019) and those discussed in class, took place within one, singular meeting.

For my participants and I, scheduling the time to meet was going to be difficult as we all worked demanding, full-time jobs. Tim suggested offering three shorter meetings: one to determine the prompt, one to weave, and one to “tie the knot.” Putting faith in my professor, I agreed to three meetings. However, I was feeling anxious about finding the time and began to question if my participants would be able to commit to the meetings. It’s hard to braid three strands together if two of the strands aren’t even there and I didn’t have a Plan B.

Thankfully, the participants were able to make time for this work, adapting with the assistance of Zoom video conferencing. The intention of the first Zoom meeting was to explain the métissage process and to collectively determine a prompt. Amanda brought forward the following prompts, formulated in discussion with Tim:

Seeking participant feedback, the following prompt was decided upon: “What do inclusive classrooms look like, sound like, and feel like?” Participants were invited to respond to this prompt in whatever way felt comfortable to them and, if they chose to write, to consider a one-page maximum response, as we would be sharing and analyzing all our work collectively. One member asked if we could immediately begin to discuss the prompt to generate ideas. This caught Amanda off guard. Unsure on how to respond, Amanda discussed the idea with the group. They all consented and began brainstorming ideas. Ideas were also included in the Zoom chat, which later became part of one of the participants’ written responses. From the responses, the group identified a shared curiosity around perspectives of students, teachers, and parents, which was taken into consideration for their separate written responses.

The initial meeting was intended to last no more than 45 minutes and I assumed we could finish it up in about 15 minutes—explaining how métissage works and deciding on a prompt couldn’t possibly take too long, especially with educators. Surprisingly, it ran for 80 minutes, 65 of which were on-topic. It had been a while since we talked outside of our group chat, so some of this time was spent catching up. I was nervous about guiding the conversation and switching from friend to researcher. This was my first time taking on a formal researcher role! With a shared interest in the topic, though, the conversation continued to flow, and my nerves began to fade. In my research journal, I wrote:

“Am I taking enough notes? Am I recording properly? It’s hard to listen, respond, note-take all at the same time.”

I am glad that I took Tim’s suggestion and recorded this meeting with two separate devices (through Zoom and through an audio recording on a personal device). I also copied and pasted the Zoom chat into a Microsoft Word document, just in case. There was a lot of rich conversation that I didn’t want to risk losing because of technical errors. Despite the benefit of online meetings (i.e. ease of recording, ability to provide multimodal contributions), there was a shared concern about ethical considerations of storing information online: does anything ever really leave the Internet? While I was unable to quell those concerns (as I, too, shared them), it is something to consider for future online meetings.

Working With Prompt for Writing Our Pieces

With a prompt finalized, participants had 10 days to formulate their responses prior to our next meeting. In the métissages that took place within the span of one meeting, writing time was limited. Bishop et al. (2019) suggested limiting written responses to 300 words for sessions under 3 hours and t for sessions between 1.5 to 2 hours, “five minutes is plenty of time to come up with a sufficient narrative to create a shared experience of métissage” (p. 7). With a timeframe set by our limited availability to meet, Amanda wondered if 10 days was too much:

“Ten days to write—that’s more than enough time! I can reflect on our first meeting, write, walk away, come back to it, edit, polish… Wait. Do I want their answers to be polished?”

I wrote this after our first meeting and laugh now looking back at it. We all ended up writing our responses in the 24-hours prior to our second meeting. There was plenty of time for reflection and for paying attention to how inclusion showed up in my own classroom over those 10 days, but life took over and took away time I thought I had to write (I was busy writing report cards instead). While it would have been more convenient to have everyone write at the same time within the limits of a set meeting, the freedom to write when and where was comfortable was what I personally needed for the words to flow. This additional time allowed me to think more purposefully about inclusive classrooms and to reflect on my own experiences in different environments, which I don’t believe would have happened with a shorter timeframe. If I had 15 minutes to write my narrative alongside everyone else, I can guarantee that I would have fumbled my words, left out important details, and produced work that could have used more time. Reading my response now, weeks later, I wouldn’t add or change anything. The words came to me in the comfort of my home, free from the pressure of finishing at the same time as everyone else. Being able to walk away with the prompt and write when it worked best for me, in a format that resonated with me, is an inclusive practice. As a participant, I appreciated this. As a researcher, I couldn’t help but feel the stress of a looming deadline and having 5 days from Meeting 2 to braid, analyze, and submit a final report.

Second Meeting, Sharing Our Pieces and Finding Our People

For the second meeting, which occurred in person, participants brought their written responses to share. Each written response took a different format: one person wrote a narrative, one organized their thoughts into a table, and one wrote a poem. This was exciting as it showed that métissage itself is an inclusive process. Amanda and the co-participants took turns reading their complete response aloud, listening for connections, emerging themes, and words that resonated.

I was immediately worried about how we would weave these three formats together. While listening to the first participant’s narrative, I felt a connection. I was listening to a story being told, not a research project. The words they used resonated with my own experiences. Within the first breath, they shared,

“I try to be as careful with words as I can because once you put them into the universe, you can’t take them back.”

This makes me think about all the mistakes I’ve made as a teacher and how I wish I could go back and change past practice, such as doing round robin readings and not having conversations I should have had because of not knowing what to say. This participant also spoke to knowing who your “people” are. Finding your people seems to be a never-ending journey, but it feels like home when you find them. I have found my teaching people, my university people, my queer people. These are the folx to whom I can open up. I can be authentically me. I am currently sitting at the table with my people, which played an important piece in deciding what writing to bring to that meeting.

The participant also discussed spirituality, which initially made me uncomfortable because of my relationship with the religion that was forced upon me as a child. However, this discomfort shifted as I listened to their words: it’s about building connections. “One heart, one mind.” Lastly, they shared about the work of resurgence. Decolonization is the work of settlers; Indigenous folx are responsible for resurgence.

I began to think of how I can weave these words into my own classroom practices but am also aware that I need to consider how these ideas will weave with the words of the next participant. I was curious how this next participant was going to share their words, as they organized their thoughts into a table. I assumed they would read down the columns, like individual poems. However, they read across the rows, explaining what inclusion looks like, sounds like, and feels like for students, teachers, and parents. I found myself quickly taking notes, as this participant also added explanations as they went, ensuring we were able to understand the message they were trying to convey. I also started noting the themes of emotional safety, authenticity, and physical space. As I do not have children, I was really interested to hear a parent’s perspective. Their love for their children and passion for adapting to the needs of their students was clear. It was hard not to interject with connections and questions at this point.

Finally, I shared my response, written as a poem. I wish I had slowed down my reading so that certain words and phrases could linger, but I was excited to begin discussing and navigating the weaving of our work.

After reading, we as a group (researcher and participants) shared what pieces resonated with us and started making connections across the written pieces, but also to other personal stories that were not included in the writing. This sense of shared struggle, of shared experiences despite our differences, helped build kinship. This felt more important than deciding how to weave our words together, which was the initial goal of this second meeting. Realizing the limitations of a 45-minute meeting, Amanda asked the participants how they wanted to proceed with weaving our words together. As a group, they opted to identify themes, which would become the braids, and then Amanda would instead work independently on the first draft of weaving the braids. The themes we identified included: emotional safety, who inclusion is for/by, relationships, decolonization, authenticity, and spaces. The group highlighted some written words that spoke to these themes and decided instead to use our remaining time to discuss our experience with this process and connect over shared experiences.

After sharing our written responses, I grew nervous about navigating the next piece of the métissage. First, I was concerned with my ability to identify themes. I was also apprehensive about how much space I would take up in the discussion of themes. While I took my own notes during the sharing (despite wanting to give my undivided attention to listening to the others), I chose to let the two of them speak to their connections first, so that I wasn’t putting ideas in their head. As they were speaking to what they noticed, I was able to join in. It was reassuring to hear that we were all noticing similar themes. One of the participants turned the conversation to the fact that none of us really touched on the financial aspect of inclusion, which can be a defining factor. I would not have considered this without them.

Before and after the second meeting, I recorded and transcribed my thoughts. On my way to the meeting, I reflected:

“Honestly, I’m a bit nervous because there isn’t a set formula for how this works. So, the participants have all submitted their stories to me and I’ve printed them out, ready to go. (...) I think that just because it’s such a flexible format, I’m really nervous going in, even though I know that the conversation is going to be a strong conversation. Honestly, I’m also a bit nervous about recording because we’re meeting for lunch, so that it was a more comfortable location. (...) I am nervous. I don’t feel like a pro, which is completely normal because I’m not, but I feel like I need to be. Where that pressure is coming from, I think, is really from myself and knowing that the people I’m working with, the participants, they do have high standards. They’re my friends, so that’s why they have high standards. But we’ll see how it goes. We’ll see how it goes.”

Leaving the meeting, I commented:

“I just finished the second meeting for our métissage and I knew I would feel so much better once it was done because working alongside two other people is actually really helpful.”

Embarking on a research project for the first time was intimidating; choosing métissage as a research genre helped grow my own understanding of what research can look like.

I also noted that the meeting location played a role in building comfort:

“Because we are friends outside of this, we had some time just catching up and building that level of comfort. I think in future métissages, something important to do is to build that relationship with the group of participants that you’re working with. [Meeting #2] in a food-based setting was actually really nice. It took away the formal pressure that comes with a general interview format. One of my concerns with meeting where we did was the noise level. I’m curious to listen back to the recording of the session just to see if the transcript is going to be doable. I think it will be because it wasn’t too loud but I know that background noise is personally distracting. I think in the future I’ll probably do it in a quiet meeting space and maybe order in food or have coffee or tea available, just something a little bit quieter than where we were … a little bit more private. But the place we went was the place that the three of us typically meet up at. I wanted to keep something familiar for us so we didn’t have to stress over what we were going to order.”

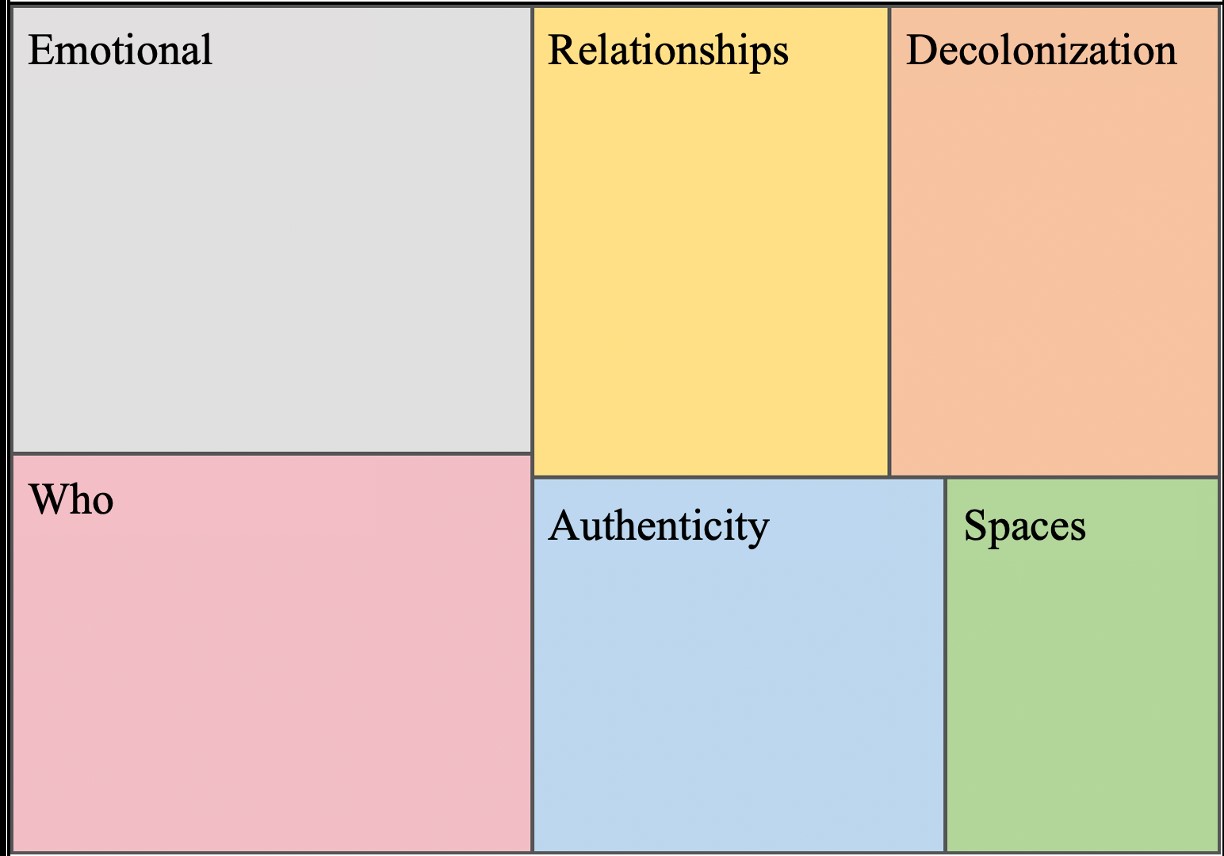

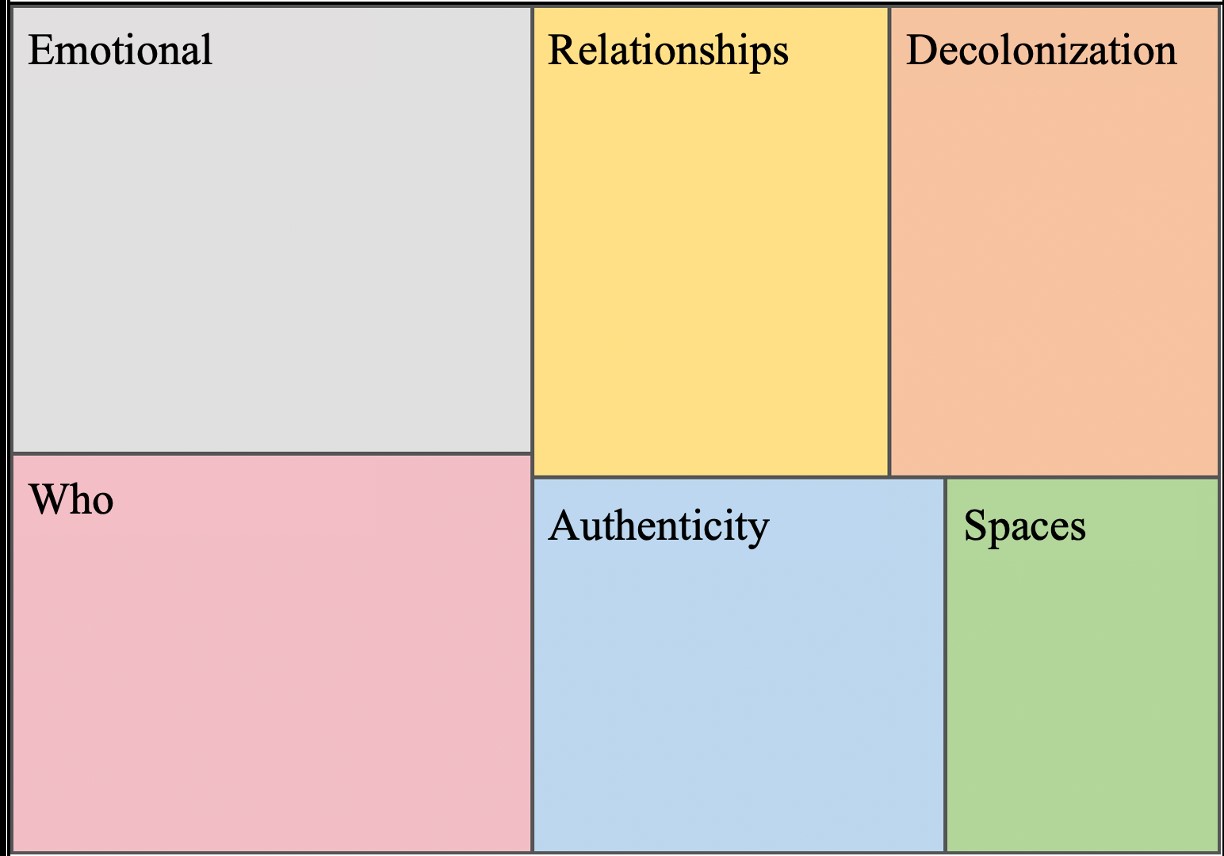

Immediately after the second meeting, Amanda inserted the group’s written responses into NVivo 14, that Tim had shown how to use in the research course, and began to code using the six themes identified by the group. The process included the thematic hierarchy chart (Figure 1) to demonstrate how frequently these themes appeared across our work. Filtering by codes provided highlighted text organized by writer. Next, Amanda took the text for each theme and began to organize it in a braided fashion, using the sharing order that took place in the meeting (Person 1, Person 2, Person 3) where possible. Once the initial braiding was complete, Amanda shared this work asynchronously via Google Drive with participants to collect feedback.

Figure 1

Thematic Hierarchy Chart

Note:

The coloured rectangles show importance by size, in terms of how

often this theme came up in conversation, with the smallest these

(Spaces) indicating least important and the largest theme (Emotional)

indicating most important.

While it might have been faster to code by hand, I’m glad I tried NVivo for the first time. Had I done this by hand, I would have used different colors to highlight different pieces of our texts, which I would have then cut up and arranged into braids. NVivo made it easy to assign the different codes to the same text and the thematic hierarchy chart allowed me to quickly see the themes that took up the most space. I was surprised to see that physical space was the smallest piece of what inclusive classrooms mean to us. I wonder if we see elements of physical spaces, such as pride flags or gender-neutral washrooms, as symbols of performative allyship rather than true elements of inclusive spaces.

Write-Up Leading to Participant Private Performance Then Public Reading

The final meeting, which was optional, was not able to occur for another 6 weeks and transpired after the completion of the course. In the meantime, to meet course deadlines, participants opted to work virtually and asynchronously in the shared document to review the braids of this métissage and share thoughts about the pieces or the process.

While I would have liked to have had time to meet with participants either online or in person for the third meeting, the asynchronous nature allowed time for us to digest the proposed braids, play with the words, and edit for understanding. One of the braids included pieces of a participant’s narrative as they had written them:

“When do classrooms feel inclusive? When do they not? When they are led by Indigenous elders and knowledge keepers. When they are led by ignorant, problematic, narrow-minded folks who uphold the White heteronormative colonial patriarchy.”

In comments in the margins, this participant clarified what they meant and another participant offered different formatting, which the first participant agreed to edit to improve readability:

“When do classrooms feel inclusive? When they are led by Indigenous elders and knowledge keepers. When do they not? When they are led by ignorant, problematic, narrow-minded folks who uphold the White heteronormative colonial patriarchy.”

This type of collaboration worked for us because we were used to working like this and trusted that we wouldn’t delete or edit each other’s words without conversation; I might not take this approach with other participants.

We also noticed some repeated lines. This happened during coding and I decided to leave the repetitions for participant feedback. Participants noted that they liked the repetition because it emphasized what inclusion is all about:

“We teach students first, not curriculum. We are not empty vessels, waiting to be filled. We are whole. We are complete.”

Participants commented that reading our woven words was an emotional experience that needed to be shared. Despite this happening online, I wanted to meet with the group in person for a more formal “conclusion” to this process.

Creating the métissage, reporting on the process, and writing a paper had met course requirements for Tim’s graduate research methods course. However, Tim encouraged Amanda to pursue completing the study by creating a performance of the métissage. Approximately 6 weeks following the second meeting, participants met virtually to read the braid aloud and share any final feedback or reflections. Ideally the reading of the braids would have been recorded to be shared in an audio-visual format. However, participants expressed concerns around anonymity with using their actual voices. Many employers have fiduciary clauses in their employee contracts, which prevent employees from critiquing their employers. While Amanda did not believe any personal critiques of employers occurred in the work, calling for more inclusive practices might imply otherwise to sensitive employers. The participants recognize that inclusion is the work of everyone, and limitations are largely in place due to systemic barriers that were deeply woven into society. The participants did, however, offer their words to be read by others, an extract of which is in the opening section of this article (Culver & Hopper, 2023).

In addition to conducting a thematic analysis of the written pieces of the métissage, Amanda also recorded and transcribed the two meetings with participants to provide additional commentary to the thematic analysis.

When I was reading about métissage as a genre, one of my primary critiques was that authors rarely shared the completed braids. Bishop et al. (2019) stated that “métissage can be both an event and artifact that could lead to individual and/or collective change” (p. 4). Considering that métissage can be an artistic representation of stories, I was disappointed to read examples focused solely on written text. If there was a way to capture the event of métissage, such as a video or recording, that could then be shared, the research genre quickly becomes more accessible. In the course journal, Tim agreed and suggested that, as course requirements were completed, we should explore ways of converting the métissage into a performance piece that could then be written about.

Within the graduate course, upon completion of our research studies, students were asked to share our work with our classmates. I took this as an opportunity to turn the braids into a performance piece. I chose the braid created around the theme of “emotional safety” as the one to perform as it had the largest area in the thematic hierarchy chart. I identified each speaker by fonts and colours chosen by participants of the study. A script was provided to classmates who volunteered to read. Others were able to follow along with the text, which was projected for display (see similar performance in Culver & Hopper, 2023). Hearing our words woven together was powerful. Immediately, I wondered how to share these braids with the world. Working with Tim, we then approached the participants with media consent forms to make a public performance of our métissage to be read by different people to protect their confidentiality.

Once participants gave permission for their words to be recorded and shared by other performers, I was excited. This meant that their words and ideas would be shareable and easily accessible. When I met with the performers to read the braids, I was able to sit and listen to our words come to life through other voices (see Culver & Hopper, 2023). As this performance happened well after the meeting where we first shared our words, I was able to notice new things. The performers' voices highlighted different parts of the braids compared to our initial reading, which helped me see some repeated phrases that I had skimmed over before. Hearing someone else read my own words was more powerful than anticipated. I remember thinking, “Wow, I wrote that?” Once the performance was complete, I initially felt at a loss for words. I was overwhelmed with gratitude for the participants choosing to write and share these words and for performers willing to bring the piece to life in a way that others could access. The voices blended well together, and their emotions reflected our own, despite coming from different backgrounds. I raise my hands to those who have helped bring this project to life. Hych’ka.

In reflecting on the confessional tale process, Amanda returned to the initial research question: “How do we make classrooms more inclusive, specifically through a SOGI lens?” This was their goal to research in their PhD. However, the circumstances of doing the métissage, time, and access to queer-identifying colleagues who were able to do the research project, meant this was not possible.

To my surprise, the métissage process itself began to answer this question. After completing the métissage, it became clear that the first step to creating inclusive classrooms is recognizing the intersectional identities of our students. Marginalized voices were given space at the table for this métissage; our identities were recognized and welcomed. We listened with open ears and open hearts. By weaving our stories together, we created an intersectional voice for what inclusion should look like, feel like. The weaving also revealed that a culture of empathy and understanding needs to be fostered in all classrooms. Similarly, métissage as a research genre also requires a culture of empathy and understanding.

The confessional perspective on creating the métissage offered what Denzin and Lincoln (2018) called the writer-as-interpreter insights, both on the co-meaning-making process for the participants as a group (including the researcher), but also for future researchers using métissage or confessional; in particular, insights on (a) how the researcher works within uncertainty, (b) a negotiated relationship within a friend group, and (c) the participatory process of the métissage process where the text is more genuinely created by the researcher with the participants. The intent of this confessional is to show, as Denzin and Lincoln (2018) concluded, “a radical, participatory ethic, one that is communitarian and feminist, an ethic that calls for trusting, collaborative nonoppressive relationships between researchers and those studied, an ethic that makes the world a more just place” (p. 80). As well, Douglas and Carless (2012) noted that the traditional (positivist) paradigm requires a separation between the researcher(s) and the participant(s), on the basis that any kind of personal involvement would (a) bias the research, (b) disturb the natural setting, and/or (c) contaminate the results. Further, Owton and Allen-Collinson (2014) on their confessional tale on researching with friends noted that more traditional ethnography using a realist approach would similarly see closeness between researcher and participant creating some type of contamination to a legitimate view of the phenomenon being studied. However, we as authors maintain that our analysis of the métissage agrees with Owton and Allen-Collinson’s (2014) contention that a close and trusting relationship prior to doing research is an asset for rich insights on the phenomena: “Emotional involvement and emotional reflexivity can provide a rich resource for the ethnographic researcher, rather than necessarily constituting a methodological ‘problem’ to be avoided” (p. 283). In the métissage, the close connection to the phenomena of the need for inclusivity that the researcher and participants have struggled with prior to doing this research, allowed the research process to happen over a short period of time, and to be rich in content in a way that those who do not suffer the challenges of inclusivity on a daily basis, need to access.

This confessional article embeds the Culver and Hopper (2023) métissage through the performance piece shared via YouTube, but also foregrounds the voice of the researcher, sharing what actually happened for them, through different levels of emotional recall on the research process, adapting in relation to what literature recommends should happen. Messiness and anxieties were shared as a pragmatic process evolved that made sense within the realities of the researcher and the participants whose lives demanded different priorities from the research process. The highly confessional personalized account viewed from hindsight, journal reflections and ongoing conversations with Tim during the graduate course and subsequently beyond, may help to reassure other researchers to respect the dynamic of qualitative research. The confessional account reveals how the métissage process promoted a genuine collaboration process with words, phrases and themes selected and shaped by the participants, including the researcher, who came together around a common concern and commitment to promote inclusive spaces. Anxiety in doing research is to be expected for novice and seasoned researchers; however, the honesty in relation to process is not always promoted (Sparkes & Smith, 2014). In this confessional account the dialogic between reporting on Amanda’s anxieties around having time, having the expertise to do justice to their peers' work, and the reflections on regrets on being part of the problem in their past, locates the researcher as in the research rather than standing outside. Linking to and moving on from the literature through personal accounts of what the researcher was thinking, offers valuable autoethnographic insights on research process that is rarely neat, without tension, or easy to pursue. Returning to Cox et al. (2017), the métissage and the confessional insights offer an interwoven insight on the phenomena of inclusivity from the perspectives of three witnesses from marginalized groups, resisting grand narratives, instead celebrating the local and personal to inform a goal to decolonize how we see and act in the world, “a process of dialogue and action” (p. 53), to evoke a sense of empowering community praxis.

The Culver and Hopper (2023) métissage performance challenges those responsible for creating inclusive spaces to hear the voices of those who experience exclusion saying that they need to have someone to advocate for them; having supportive administration is crucial. A SOGI lens facilitates the recognition of gender diversity, so gendered language (such as “guys” or “boys and girls”) should be minimal, if not completely obsolete from classroom spaces. Those who enter learning spaces need to see themselves and others reflected in materials and resources. While this is beneficial as seen through a SOGI lens, inclusion, in turn, benefits all students, whether Indigenous, disabled, or from any other marginalized group. Inclusive spaces assist in “finding your people.” These spaces move away from colonialism and are instead built on relationships. Students first, not curriculum.

Regarding inclusive practices, it is worth sharing some of the comments and observations made from participants throughout the study, particularly during Meeting 2. The financial aspect was largely missing from this work. Governments and school districts need to invest in equitable resource distribution. All physical learning spaces need to be accessible to all, rather than adapted as an afterthought. Students should not have to transport a ramp so that their wheelchair can enter a space. Buildings need to be in good repair for the health and safety of all those who enter it. Financial equity allows access to resources that are culturally sustaining. There is no reason for picture books with racist imagery to enter the hands of students. Toss those books and spend the money on books that do not harm students’ sense of being who they are. Inclusion is a collective effort.

Some models of schooling assume that the learner is an empty vessel, waiting to be filled. Inclusive practices recognize that the person is already whole (Freire, 1985). They are complete. We are not starting from scratch. The system should not have to be turned on its head to meet the needs of the learners entering the space. Accessibility to education should not be an afterthought.

Speaking to the process of the métissage itself, participants noted appreciation for the inclusive nature of participating. We all loved seeing the different formats each of us brought to the second meeting: a narrative, a chart, a poem. As noted by others (Bishop et al. 2019; Cox, et al. 2017) the process of métissage met the needs of participants by allowing them to engage in a way that made sense to them. One participant concluded our second meeting with, “I feel, like, the warm and fuzzies just from the process.” This process, much like inclusive practices, encourages the cultural teaching of listening with three ears: two on your head and one in your heart. Empathy is at the heart of inclusion.

Benson, N., Lemon, M., & Thomas, C. (2020). (Be)coming together: Making kin through stories of language and literacy: Using métissage as a research praxis. Language & Literacy, 22(1), 39–58. https://doi.org/10.20360/langandlit29515

Bishop, K., Etmanski, C., Page, M. B., Dominguez, B., & Heykoop, C. (2019). Narrative métissage as an innovative engagement practice. Engaged Scholar Journal: Community-Engaged Research, Teaching, and Learning, 5(2), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.15402/esj.v5i2.68331

CBC News. (2018, March 19). Beyond 94: Truth and reconciliation in Canada. https://www.cbc.ca/newsinteractives/beyond-94

Chambers, C., Donald, D., & Hasebe-Ludt, E. (2002). Creating a curriculum of métissage. Educational Insights, 7(2). https://einsights.ogpr.educ.ubc.ca/v07n02/metissage/metiscript.html

Cox, R. D., Dougherty, M., Hampton, S. L., Neigel, C., & Nickel, K. (2017). Does this feel empowering? Using métissage to explore the effects of critical pedagogy. International Journal of Critical Pedagogy, 8(1), 33–57. https://libjournal.uncg.edu/ijcp

Culver, A., (2022). Queer inclusive spaces: A métissage. [Unpublished paper]. School of Exercise Science, Physical and Health Education. University of Victoria.

Culver, A., & Hopper, T. (2023, February 14). Queering inclusive spaces: A métissage [Video] YouTube. https://youtu.be/H6xznYyqahs

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2018). The Sage handbook of qualitative research (5th ed.). SAGE.

Douglas, K., & Carless, D. (2010). Restoring connections in physical activity and mental health research and practice: A confessional tale. Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise, 2(3), 336–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/19398441.2010.517039

Douglas, K., & Carless, D. (2012). Membership, golf and a story about Anna and me: Reflections on research in elite sport. Qualitative Methods in Psychology Bulletin, (13). https://shop.bps.org.uk/qmip-bulletin-issue-13-spring-2012

First Nations Education Steering Committee. (2022). How are we doing? report. http://www.fnesc.ca/how-are-we-doing-report/

Education and Child Care. (2017). Sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) in schools. Government of BC News. https://news.gov.bc.ca/factsheets/sexual-orientation-and-gender-identity-sogi-in-schools

Freire, P. (1985). Reading the world and reading the word: An interview with Paulo Freire. Language Arts, 62(1), 15–21. https://ncte.org/resources/journals/language-arts/

Herriot, L., Burns, D. P., & Yeung, B. (2018). Contested spaces: Trans-inclusive school policies and parental sovereignty in Canada. Gender and Education, 30(6), 695–714. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2017.1396291

Hopper, T., Madill, L. E., Bratsch, C. D., Cameron, K. A., Coble, J. D., Nimmon, L. E., & Bratseth, C. D. (2008). Multiple voices in health, sport, recreation, and physical education research: Revealing unfamiliar spaces in a polyvocal review of qualitative research genres. QUEST, 60(2), 214–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2008.10483578

Inclusion BC. (n.d.). What is inclusive education? https://inclusionbc.org/our-resources/what-is-inclusive-education/

Inclusion Canada. (n.d.). Inclusive education. https://inclusioncanada.ca/campaign/inclusive-education/

Kluge, M. A. (2001). Confessions of a beginning qualitative researcher. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, 9(3), 329–335. https://doi.org/10.1123/japa.9.3.329

Kovach, M. (2018). Doing Indigenous methodologies: A letter to a research class. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (pp. 383–417). SAGE.

Lowan-Trudeau, G. (2017). Narrating a critical Indigenous pedagogy of place: A literary métissage. Educational Theory, 67(4), 509–525. https://doi.org/10.1111/edth.12261

Meyer, E. J., & Keenan, H. (2018). Can policies help schools affirm gender diversity? A policy archaeology of transgender-inclusive policies in California schools. Gender and Education, 30(6), 736–753. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2018.1483490

Owton, H., & Allen-Collinson, J. (2014). Close but not too close. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 43(3), 283–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891241613495410

Peter, T., Campbell, C. P., & Taylor, C. (2021). Still in every class in every school: Final report on the second climate survey on homophobia, biphobia, and transphobia in Canadian schools. Egale Canada Human Rights Trust. https://egale.ca/awareness/still-in-every-class/

Schultze, U. (2000). A confessional account of an ethnography about knowledge work. MIS Quarterly, 24(1), 3–41. https://doi.org/10.2307/3250978

Sparkes, A. C. (2002). Telling tales in sport and physical activity: A qualitative journey (pp. 57–72). Human Kinetics.

Sparkes, A. C., & Smith, B. (2014). Qualitative research methods in sport, exercise and health— From process to product. Routledge.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Truth and reconciliation commission of Canada: Calls to action. https://ehprnh2mwo3.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf

Van Maanen, J. (1988). Tales of the field. The University of Chicago Press.

Worley, V. (2006). Revolution is in the everyday: Métissage as place of education. Discourse, 27(4), 515–531. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596300600988853