Slowing, Desiring, Haunting, Hospicing, and Longing for Change: Thinking With Snails in Canadian Early Childhood Education and Care

Iris Berger, University of British Columbia

Emily Ashton, University of Regina

Joanne Lehrer, Université du Québec en Outaouais

Mari Pighini, University of British Columbia

Authors’ Note

Iris Berger https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9992-1453

Emily Ashton https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8571-8967

Joanne Lehrer https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3290-8027

Mari Pighini https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8207-0867

This work was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) of Canada and the Centre for Educational Research, Collaboration, and Development (CERCD) at the University of Regina.

Correspondence concerning this article can be sent to Iris Berger at iris.berger@ubc.ca, or Emily Ashton at emily.ashton@uregina.ca, or Joanne Lehrer at joanne.lehrer@uqo.ca, or Mari Pighini at mari.pighini@ubc.ca

___________

This paper is a collective attempt to respond creatively to a research project we were part of entitled Sketching Narratives of Movement: Towards Comprehensive and Competent Early Childhood Educational Systems Across Canada (2019–2022). The project was interrupted and transformed by the COVID-19 pandemic. As well, the project gained additional significance when the Government of Canada made a historic announcement in its April 2021 budget to invest nearly $30 billion dollars in a Canada-wide early learning and child care plan.[1]

As outlined below, we affectionately refer to our work as “the snail project.” We share our slow process of thinking, collaborating, wondering, and pausing along with the figure of the snail as we improvise a nonlinear path towards an unknown future. We think-with various theories of change as a response to narratives shared by participants in the project’s knowledge mobilization events: two public webinars and the production of a series of short video interviews.[2] The first webinar (June, 2020) entailed two panels consisting of policy experts and advocates from across Canada, sharing their visions and hopes for the future of Canadian Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC). The second webinar (November, 2020) brought together a diverse group of early childhood educators, working in different types of ECEC programs across the country, to discuss what being an educator meant to them in that historical moment. The third event (February, 2021) was a series of short videos wherein Indigenous and international early childhood scholars shared stories of innovative curricula, research, and policy that could inspire us as we contemplate provincial and territorial ECEC systems in the process of becoming.

The pandemic simultaneously (re)inscribed ECEC with familiar discourses and narratives, such as being framed as an “essential service” to support “essential workers” (Friendly & Ballantyne, 2020), yet, it also issued forth the potential for new imaginaries. No longer was ECEC solely framed as a means to encourage women’s workforce participation, it was suddenly positioned as a critical community life-sustaining space for entire systems (health, economic, educational) stressed by a pandemic. Amidst the attention, however, “slimy” traces of chronic neglect, underfunding, and undervaluing of ECEC were gleaming. Given the unpredictable momentum, we argue that it is essential that we open up ECEC to different narratives of movement. To this end, we offer five theoretical capsules titled: Slowing, Desiring, Haunting, Hospicing, and Longing as provocations for storying care otherwise and for stirring ethical consideration with potentialities for slow activism in ECEC.

Slowing

The snail—in its slowness, smallness, sliminess, and spirals—has become entangled with our curiosities about narratives of movement and change in ECEC. Movements that desire to counteract capitalist neoliberal, quick-solution, market logics and discourses tethered to labels such as the economy, recovery, and normalcy. Snails might help us disrupt the timescale of the human species and make us wonder what movements of change are made possible if we think ECEC across a range of temporal scales. In the Life of Lines, Tim Ingold (2015) invoked the figure of the snail to reverse a conventional theory of movement as drawing a line between two predefined dots. Instead, he proposed a movement of drawing-in and issuing-forth along lines of becoming. In its movement, Ingold (2015) stated metaphorically that every snail becomes a line—a living line—a slimy trace—that is never perfectly straight because a living line continuously attends to its path “fine-tuning the direction as the journey unfolds” (p. 139), pausing to recoil—to recollect, gather, and think—and then issuing forth—tentacles feeling/imagining the way, “improvising a passage through an as yet unformed world” (p. 140). In this paper, we trace our thinking with snails as we wonder about the “widespread malaise” heightened by the pandemic, and how we might stay with, even follow, the snail’s slow, small, slimy traces as a “site of contest” (Hartman & Darab, 2012).

Inspired by The Slow Science Academy (2010) manifesto slogan that states: “Bear with us, while we think,” Bird Rose (2013), in her provocative manuscript, “Slowly Writing into the Anthropocene,” argued for a slow movement imbued with thought and attention as an antidote to our sense of “lack of capacity to change things we know need changing” (p. 6). In the rush to cobble together a Canadian national ECEC system primarily on budgetary terms, we perceive that negotiated thinking succumbed to pressure for a rapid signing of bilateral agreements between the Federal government and provincial and territorial jurisdictions.[3]

Slowing and Storying

In his distinguished lecture at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, “The World in a Shell: The Disappearing Snails of Hawai'i,” Australian field philosopher and storyteller Thom van Dooren (UMassHistory, 2020) called direct attention to snails. He spoke of the perils of conservation work and ecological documentation concerned exclusively with classifying larger species, those already “legally noticed” during a moment of ongoing crisis. A consequence of this flagship species focus is the slow disappearance of invertebrates that we will never learn ever existed because we failed to cultivate “arts of noticing” (Tsing, 2015). Snails, facing imminent extinction, are stored, anonymously, in hidden boxes in a museum. van Dooren effused his audience to shift from an ecological species-centred taxonomy of classification to an ecosystem’s taxonomy of “storying the unknown.” In “expansing storying practices,” scientists acknowledge relational connections that “tell ethical stories of the becomings of the unknown and the unrecognizable,” allowing for a reconstruction of snails’ paths through their existence. Such ethical transformation allows us to care, ethically, about that which is not seen. van Dooren (2016) discussed slow care for endangered snails, and asked, “through the support for fleshy snail bodies … what kinds of possibilities for the future does it hold open?” (p. 4).

The phrases van Dooren used to describe the snails near extinction in a lab in Hawai'i, “storying the unknown” and “expansing storying practices,” find resonances with ECEC and the theorizing we are attempting here. The pandemic revealed a crisis in ECEC provision, now a “legally visible” species at-risk, only yesterday an unknown species fighting for survival. More specifically, we see here a resonance with attention drawn to the perils of conceiving ECEC as a diminished “industry,” reduced services, and strained financial, health, social, and educational systems. Like snails and many other unseen, undocumented invertebrates, ECEC suffers the consequences of a species-centred taxonomy approach that classifies children in ECEC programs according to ages/stages, adult/child ratios, and leaves them behind in storage boxes in mostly publicly invisible ECEC settings. Instead of continuing to use service provision and school readiness discourses that echo a classification taxonomy, we embrace van Dooren’s invitation to adopt an ecosystems taxonomy of relational connections by storying the unknown.” Just like Hawaiian snails during their brief lives, children’s life-traces across and within diverse ecological spaces and places are invisible only if we choose not to notice them.

In her keynote speech at the 31st Annual meeting of the European Early Childhood Research Association, Alison Clark (2022) spoke about the need to reclaim time for children, as a way to resist the neoliberal imperative to move children as quickly and cheaply as possible toward a future that has already been mapped out for them. She outlined a slow pedagogy of place, where time is taken to pay close attention to feelings and senses. For Clark, slow pedagogies allow for being with, going off track, diving deep with children, and taking the longer view. We see connections between thinking with snail trails and ECEC pedagogies of listening and pedagogical documentation grounded in practices of revisiting and reflection where curriculum making is enacted as a movement of drawing-in—pausing to think and reflect—and issuing-forth—making tentative curricular proposals for and with children (Cameron & Moss, 2020; Moss, 2010; Rinaldi, 2006). Similarly, Kind et al. (2019) challenged speedy pedagogies in their description of artistic practices with children and materials in the studio space: “The studio is imagined as a space of collective inquiry that affords both children and educators time to dwell [emphasis added] with materials, linger [emphasis added] in artistic processes and work together on particular ideas and propositions” (p. 67).

Slowing Return to “Normalcy”

At the forefront of our inquiry is the question, “How shall we live?” (Tuck, 2018, p. 157). Amidst calls to return to normal after two and a half years of pandemic precarity, we desire to return slowly, to turn towards slow, and to not be complicit in so-called quick fixes or Band-Aid solutions. Refuting the return to normal and any illusionary of this possibility, Dionne Brand (2020) wondered about how speed and time have been slowed during the pandemic:

The pandemic situates you in waiting. So much waiting, you gain clarity. You listen more attentively, more anxiously. ‘We must get the economy moving,’ they say. And, ‘we must get people back to work,’ they say. These hymns we’ve heard, these enticements to something called the normal, gesture us toward complicity. (para. 5)

Instead, we want to think slow, to listen slow, to learn slow, to relate slow, to (re)turn slow. How might we linger with “slow”? The slime trails of some snail species “are used for communication between snails and may help them return to the same spot to rest for the day or night” (Price, 2021, para. 1).

Claire Cameron and Peter Moss (2020) claim that the pandemic has made defects in ECEC provision readily apparent. What it has also made clear is that it is “time for an ECEC revolution,” one guided by a principle of “slow knowledge and slow pedagogy” (Moss & Cameron, 2020). We know it is difficult to slow down given the $30 billion dollar investment in ECEC announcement by Canada’s federal government (Government of Canada, 2021), and the subsequent bilateral agreements with the provinces and territories. The sheer amount of the funds set to be transferred from the federal to provincial and territorial governments is unprecedented in Canadian ECEC history. But we know these agreements have been decades in the making, and represent advocates’ slow engagement with Canadian politics.

Slow is also hard to stay with when early childhood educators are underpaid and their conditions of employment so precarious. For example, in our second webinar held in November 2021, educators mentioned feeling as if they needed to make a choice between the “passion” of their job and “making a living.” Janice, an educator working in Vancouver, explained that after “putting in an 8-hour day” she also worked a “6- to 7-hour shift at night at a restaurant.” She had been working two jobs prior to the pandemic and believed that her situation was not uncommon for other educators.

We understand the desire to move quickly. After decades of feminist labour and childcare advocacy (Pasolli, 2021), there is a fear that all the public support and funding could go away with a change of government. However, speed can create, according to Isabelle Stengers (2018), “an insensitivity to everything,” whereas slowing down “means … reweaving the bounds of interdependency. It means thinking and imagining, and, in the process, creating relationships with others that are not those of capture” (pp. 80–81). A national childcare system ought not to be one of containment. It is time to make visible the limitations of current care practices. Moss (2006) raised similar questions about our vision for childcare: Are they “enclosures for applying technologies to children,” a kind of regulated care and “maintenance of hope” in the name of child “protection” and/or “readiness” (p. 73)? Or might they be children’s spaces enlivened beyond the contour of a physical space and tethered to the world with multiple lines of diverse forms and desires?

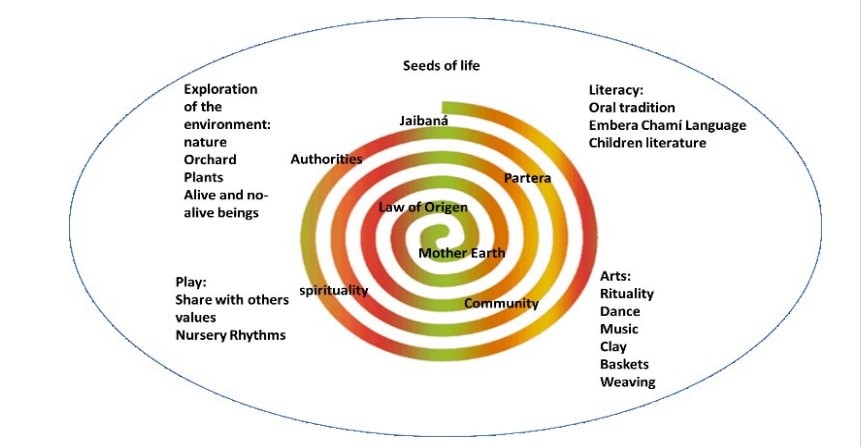

How might snails’ movements, close to earth and immersed in the fluxes of weather, disrupt the narrative of national childcare as capture? What might be missed/or reified if we continue to think ECEC through provincial, territorial, and national borders and regulations? Snail lines are very different from border lines, they do not seek to enclose (no outside and inside) but to slowly extend along multiple paths. Life, as Ingold (2015) reminded us, is not contained within bounded places but threads its way along paths in a “zone of entanglement.” What are the possibilities for children’s spaces to participate in co-weaving stories (tales/trails) of places, care, and pedagogy within their own zone of engagement? An effort to dwell in such zones of entanglement can be found in the Colombian early learning framework, De Cero A Siempre (From Zero to Forever). Researcher Luz Marina Hoyos Vivas shared in our third snail event, that this ECEC policy “attends to Colombia’s ethnocultural, linguistic, geographical, and place-based diversity” (Hoyos Vivas et al., 2021). As an example of how national policy might attend to locality and specificity, Hoyos Vivas described a participatory study from a decolonized perspective with the Embera-Chamí peoples from whose perspective the lifespan is not divided into cycles, but is a continuum in community and family life portrayed as a spiral as opposed to concentric (bordered) circles. As illustrated in Figure 1, ECEC is conceptualized as living and non-living beings who guide people in their spiritual life, transmitted through oral traditions and Mingas de Pensamiento (traditional community discussions). Children are active participants in community life and their families prepare them to undertake activities valued by the community, such as learning about the spirits of plants while planting seedlings.

Figure 1

“Pedagogic Approach for ECEC in Wasiruma Graphic Display” (Hoyos Vivas, 2020, p. 115)

Note. Used with permission.(Hoyos Vivas, 2020, p. 115)

Panelist Martha Friendly (Webinar 1) affirmed that ECEC is a “multifaceted complicated policy area” that focuses on economy, pedagogy, parents, social infrastructure, public goods, women’s rights, children’s development, and children’s rights and that these are “not at all exclusive of one another.” While Friendly was careful to note that she was not suggesting “anything goes,” we wonder if slowing down thought and opening up to difference might reveal some incommensurabilities (Stengers, 2005) that might help us rethink whether returning to normal is desirable. Can narratives promoting capitalist economies coexist with the sort of “relationships and connectedness and community” offered in a question from the webinar audience? Are these narratives commensurable? Do we want them to be? If capitalism and neoliberalism (among other things) are the problem, does slowing down and reimagining ECEC make sense without changing the material and discursive reality of our lives? In other words, is it possible for snails to coexist among steamrollers? Perhaps what the pandemic did for ECEC is highlighted “the shortcomings of the insistence on treating the early years as a market” (Bonetti, 2020, para. 6). The discourse of ECEC as a service and a commodity does not sit easily with snails and slow pedagogies. An audience member during our first webinar with policy experts and advocates wrote in the chat:

Could you share your views around these thoughts: In a webinar about public health and the pandemic, Dr. Bonnie Henry, Medical Officer of BC stated yesterday that while economy is important, it does not happen without “lives” ... however the current media and political discourses seem to separate these two. In thinking about lives, and within the world of early childhood education, learning, and care, I worry about the push for childcare without caring (for the needs of children, parents, and educators) about the push for learning without the notions of relationships and connectedness and community and partnership.

Educators who spoke in the second webinar shared with us actions they have taken to maintain an illusion of normality, sometimes at their own cost: they held meetings with children online, made and delivered activity packages, supported breakfast programs, participated in car-parades to show the children and families that they cared and “are still here,” organized outdoor gatherings to maintain and preserve connections, called children at home, and offered additional help and family support. In spite of isolation, physical distancing, and often no funding, educators focused on relationships and their connections to community. The educators hoped that the pandemic would be a catalyst for reframing ECEC—exposing the precarious nature of employment in the sector. As one educator noted, “We’re being told we are essential, but we are being treated like we are disposable.”

In her contribution to the policy and advocacy webinar, Margo Greenwood (nehiyawak/Cree) spoke about the Indigenous Early Learning and Child Care Framework (IELCCF), which forwards “distinction-based frameworks” as its ethical foundation (Government of Canada, 2018). While various Indigenous contributors came together to create the IELCCF, differences between First Nation, Métis, and Inuit peoples are honoured and inscribed in the curriculum. Distinction in this sense means that even within a shared vision, differences still matter. It means that implementation of the IELCCF embraces slowness as it states that—it will “be a collaborative effort over several years, through ongoing, open dialogue and mutual effort” (Government of Canada, 2018, p. 8).

Desiring

“Canada has child-care problems,” we are told on repeat; “We lag behind 18 others in a recent global ranking” (Klukas, 2021, para. 1). We hear that educators are undertrained, undervalued, and that there is a “recruitment crisis” (Akbari, 2021). The Early Childhood Education Report 2000 (Atkinson Centre, 2020) noted, “research continually demonstrates cross-country challenges with unstable and inadequate funding, poor oversight, inequitable access, space shortages, unaffordable fees, gaps in services and transitions, and often poor working conditions and remuneration for early childhood educators” (p. 3). These sorts of statements and findings are routine and were echoed by panel participants in our first two webinars. Most panelists start and end their remarks with lack and limit—in other words, they lock us in damage narratives as a habit of thought and response. Unangax̂ scholar Eve Tuck (2009) proposed the possibility of desire-centred research as a way to re-envision theories of change. She advocates for desire not “as an antonym to damage, as if they are opposites … desire as an epistemological shift” that makes different imaginaries and different worlds possible (p. 419).

Tuck’s (2009) refutation of damage emerged from a specific context that is important to acknowledge. Tuck (2009) requested a moratorium on damaged-centred research that obsessively documents “the effects of oppression” on “Native communities, city communities, and other disenfranchised communities” (p. 409). The consequence of this “persistent trend in research” is to instill a belief in communities that they are “depleted” and in need of external, often paternalistic, fixes (Tuck, 2009, p. 409). Instead of focusing solely on what is broken, Tuck puts forward desire as an antidote, a medicine, and a recognition of both suffering and thriving in the face of colonialism, anti-black racism, poverty, and loss. For Tuck (2009), “desire is about longing, about a present that is enriched by both the past and the future. It is integral to our humanness” (p. 417). How might a desire-based starting point in ECEC narratives of change move us towards an “elsewhere and elsewhen that was, still is, and might yet be” (Haraway, 2016, p. 31) when damage-based research is so often used to leverage resources while reinforcing a unidimensional notion of ECEC. However, as Tuck (2009) asked, “Does it actually work? Do the material and political wins come through? And, most importantly, are the wins worth the long-term costs of thinking of ourselves as damaged?” (p. 415).

When discussing what it means to be an educator in the autumn of 2021, the educators in Webinar 2 often drew on contradictory damage-based and desire narratives about quality, children’s achievement, and children with additional needs. They echo a recurring tension between ECEC neoliberal narratives focused on the future (becoming) and reconceptualist ECEC narratives of the present (being), between children in need of protection who need to be shaped and formed so they will later perform, and children as citizens with rights, right now. Tuck (2009) reminds us that desire-based frameworks draw on the idea of “complex personhood” (p. 420) where people are seen and valued as multilayered and often embody contradictions. Our intention is to (re)think our responsibility as researchers to co-construct with the educators’ stories of desire-based narratives by “splicing” (Tuck, 2009) damage-based narratives with stories of wisdom, vision, and hope.

We do not wish to erase damage-based theories of change completely, but rather to ask, as Tuck did, is it time for a shift? “Are damage-centered narratives no longer sufficient?” (Tuck, 2009, p. 415). We are not implying that desire narratives are “easy.”—Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari (1987, as cited in Tuck 2009) taught us that desire is assembled, crafted over a lifetime through our experiences by “picking up of distinct bits and pieces that, without losing their specificity, become integrated into a dynamic whole” (p. 418). The ECEC sector: advocates, researchers, educators, argues for change using damage-centred logic: a damaged system, damaged children, damaged parents, and damaged educators. What if we think with desire? If we did not have to convince the government to fund ECEC systems, what do we desire? Do we dare hope for recognition of the diverse roles of children within our diverse communities, for a reorganization of our lives with children, for multiple, contextualized, community-centred forms of ECEC? Do we even consider: What do children desire? And what of our desire to spend time playing, discovering, and caring for children, and to spend time apart, working, learning, and breathing? What does it mean to care as parents, educators, theorists, and as a community? What could happen if we dare to think of ECEC, not as a tool to kickstart the economy, but as a milieu in which to experiment with new modes of living and relating to one another?

Tibetha Kemble (Piapot First Nation) was interviewed about a project that sought to understand the needs of Indigenous children and their parents and caregivers in Amiskwaciy Waskahikan (Edmonton) as part of the Indigenous and international narratives series (Event 3). She spoke of ECEC as part of a community anti-poverty and decolonial strategy, and of talking circles as part of a non-hierarchical process to build trust, and to communicate with families in a good way:

We weren’t trying to understand what cultural practices they wanted to see in daycare, but what were their experiences in the system: access, affordability, experiences with racism, intersections with child welfare, wanting to understand the complex ways ECEC intersects with other systems and how we might affect change. (Event 3)

Instead of quick cultural activities that could be assimilated into childcare centres by settler educators in the name of reconciliation, the talking circles this project implemented explored the systemic nature of colonialism as well as the possibility to decolonize ECEC through interpersonal relationships. They engaged with damage, but the damage was attributed to systems of injustice, not to the families and children themselves, and they spliced these narratives with narratives of hope, expertise, and wisdom. These slow and repetitive relational acts began “shifting the discourse away from damage and toward desire and complexity” (Tuck, 2009, p. 422) that insist upon openness and vulnerability as starting points. The project sought to understand how culturally safe care and relationships with Indigenous people and children should be, against a backdrop of ongoing racist and colonialist child welfare practices, recognizing Indigenous parents as experts and as important contributors to improving the ECEC system in Amiskwaciy Waskahikan.

Desire is concerned with understanding complexity, contradiction, and the self-determination of lived lives. It is wisdom, agency, complicity, and resistance. As the national ECEC system takes shape, we seek to infuse our research and our activism with desire. This means allowing ourselves to imagine, to dream, to hope, to listen, to disagree, to compromise, and to ride waves of joy. As Brittany Aamot expressed in our second webinar, we need to think about ECEC other than as a way to kick-start the economy, as

a place to learn, play, grow, be cared for … The narrative of thriving early childhood communities needs to be told, families and children returning to cherished spaces after closure and restrictions, the magic and joy of children reuniting with peers and educators after this time away, that’s a beautiful story that should be shared, that outweighed the fears related to safety during the pandemic. (Webinar 2)

Hospicing

van Dooren (2019) shared the story of the “snail ark,” a captive breeding lab run by the Hawai’i State Government’s Snail Extinction Prevention Program (SEPP). The ark—a more accurate image of which is a series of fish tanks in industrial fridges—are singularized, replicate microcosms of the forest. Every 2 weeks the vegetation gets replaced, the tank gets sterilized, and the inhabitants get counted. The Hawaiian Government’s SEPP cares for snails that can no longer survive outside these controlled conditions. The typical metaphor for endangered species management is an emergency room. This implies intensive care and “a meaningful prospect of recovery. That, with some attention, species might be patched up and sent on their way” (van Dooren, 2019, para. 4). But recovery for most snails in the ark is unlikely. The majority will not be reintroduced to the forest; there is no exit from the ark. These are practices of “long-term care that are, in the final analysis, acts of delaying the inevitable. Extinction in slow motion” (van Dooren, 2019, para. 11). Perhaps, as van Doreen (2019) suggested, instead of an emergency room, the ark is “something more akin to a hospice” (para. 4). How does this revision shift our imaginary of care—from intensive care to palliative care? To slow care? What if hospice isn’t a noun, but a verb (Machado de Oliveira, 2021)? Hospicing can be a pre-emptive practice of remembering before snails are gone. It is love and preparation for haunting.

The snails help us think about what is (un)sustainable in our worlds, and how care does not stop when someone is not self-sufficient (as if anyone actually ever is or was). We also consider what needs to be hospiced in order for something new and different to emerge. Vanessa de Oliveira Andreotti and colleagues (2015) proposed hospicing a system as practices of living with a dying modernity, which includes neoliberalism, capitalism, colonialism, extractive industry, species extinctions, unequal distributions of power, and lots of other damage, but also human rights, women’s rights, children’s rights, and all those conveniences that make daily life a bit easier, from cars and Instapots to Netflix.

Hospicing would entail sitting with a system in decline, learning from its history, offering palliative care, seeing oneself in that which is dying, attending to the integrity of the process, dealing with tantrums, incontinence, anger and hopelessness, ‘cleaning up’, and clearing the space for something new. This is unlikely to be a glamorous process; it will entail many frustrations, an uncertain timeline, and unforeseeable outcomes without guarantees. (Andreotti et al., 2015, p. 28)

We know that modernity is killing us, but it is also in us—it is us. And modernity cannot be separated from market-based ECEC, low educator wages, and hierarchies of child development knowledge. It is ECEC as an essential service, necessary for economic recovery and women’s labour force participation. It is the exhaustion the educators spoke about in Webinar 2, their disposability and precarity—captured so well in other papers in this special issue (Massing et al., 2022; Maeers et al., 2022). The tenacity of modernity is evident when we think of theories of change that document damage, propose solutions, but because the issues are often ingrained systematically, the pattern then repeats for the next researchers to come along. Modernity holds strong to “stories of the established disorders” (Haraway, 2004, p. 47) used to advocate for ECEC as a panacea for the economy, for patriarchy, for crime, for individual failure (in school, in life).

At its core, hospicing involves slowly accompanying a system that cannot be fixed, providing care as it dies. “Whether we like it or not,” van Dooren (2019) asserted, “we now find ourselves living on a hospice earth” (para. 13). This does not mean “embracing pessimism” (para. 16), but rather it might encourage us to develop what Anna Tsing et al. (2017) have called “arts of living on a damaged planet.” This “facing up to death and dying” through hospicing “is one such art, essential for our times” (van Dooren, 2019, para. 15). Importantly, hospicing does not preclude compromises (such as the federal-provincial ECEC agreements, or the snail ark), but instead helps us realize that “advocating for expansion or radical transformation of the system (e.g., through equity, access, voice, recognition, representation, or redistribution) is insufficient” (Andreotti et al., 2015, p. 7). So, while a national plan may bring in a necessary influx of childcare spaces, lowered costs for families, and, in some places, increased educator wages and post-secondary education subsidies, it does not get us out of the system that makes these interventions necessary in the first place. It is easy to be “enchanted” by the promises. Hospicing doesn’t “minimize our complicity in the very things we are contesting” (Stein & Andreotti, 2017, p. 179). It is “messy, uncomfortable, difficult, deceptive, contradictory, paradoxical…prepare for your heart to break open” (Machado de Oliveira, 2021, p. 180). Nevertheless, hospicing is how we might practice care as we enact our “slow activism” (Liboiron et al., 2018). It might “be affirmative, even transformative” (van Dooren, 2019, para. 16). We are left with many questions, modified from Stein and Andreotti’s (2017) proposals: What kinds of futurities do we want for ECEC, and for ourselves within it? To what extent have dominant discourses and imaginaries “shaped our desired futurities, and what kinds of harms would be required to achieve them” (p. 178)? “What if it is not possible” for ECEC (in its modern, technical forms) “to fulfill these desires” (p. 178)? If "we let go of these desires or at least loosened our grip on them, without necessarily exiting [ECEC], what else might become possible?” (p. 178). What can we desire if we hospice ECEC as we currently know it along with the neoliberal extractive colonial capitalism system?

Haunting

Tuck and Ree (2013) theorized haunting to contest claims of past-present and/or future settler-colonial innocence and to disrupt easy-White-hero-justice stories. Haunting is being affected by the unresolvable—ghosts that reject solutions as justice. It is about the stickiness of slime—traces of settler colonialism written into a history of erasure. But haunting is also a “constituent element of modern social life” (Gordon, 1997, p.7). Hauntology ought to slow us down. Hauntological logic challenges us to ask new questions: How do various ideologies haunt childcare? Where do discourses go when they die? And how can thinking with snails and haunting help us reimagine change in ECEC?

Our posing of difficult questions, our insistence on challenging economic and developmental rationales for ECEC, our stubborn refusal of quick fixes, our preoccupation with politics and issues of identity and justice, and our desire to create places of care and pedagogy with young children that reflect a vision of community belonging, magic, and joy in the present moment, these are examples of how we haunt decision-makers, students, and practitioners, challenging taken-for-granted knowledges about what is possible and realistic, and what is best for children and families. How we haunt the collective imaginary involves relentlessly reminding ourselves that the boundaries we set are not inevitable. The snail teaches us that with care, thought, and attention, we can bind ourselves together and reimagine possibilities.

In our first webinar, multiple panelists remarked on the generative potentiality of the supposed postpandemic moment—“What seemed impossible … now seems possible” (Andrew Bevan, Panel 2)—but they also seemed resistant to consider that the moment might invite different imaginaries. In some cases, we think there is a distinction to be made between slowness as an emergent praxis and the claim that the pandemic allowed, in panelist Don Giesbrecht’s words, for some sort of “an awakening, an affirmation” that was not present before. To qualify this further, Don said, ECEC “has been a political afterthought” for a long period, yet its recognition as an “essential service” does not encompass the sorts of transformation we desire. Another panelist, Bevan, remarked in the Zoom chat that “if the question was, are there other new arguments to be made at this particular moment in support of a national childcare system, I think the basic answer to that is no”. The underlying rationale was that what has long been said about ECEC remains true and what has changed now “is context” (Bevan). These narratives reflect the unresolved ghost of ECEC, the narrow framing of ECEC as a service and as a substitute for a (working) mother’s care.

A question from an audience member challenged this haunted way of thinking ECEC:

I just want to clarify, is the panel addressing early childhood education as a service? Is this how we are invited to continue thinking about early childhood education? If this is the case, what can be created, pedagogically, when “service” is the concept that frames our conversations? (Cristina Delgado Vintimilla)

Tuck and Yang (2011) discussed the politics of recognition and teleological resistance strategies as prescriptive theories that assume change is always linear, progressing from oppression to liberation, from bewildered to enlightened:

Such conceptualizations of resistance rely on developmental or progress-oriented theories of change, the same theories that presume the “improvement” from savage to civilized, wild to domesticated, and unschooled to educated. Theories of change that suppose linear progress are characteristic of Western philosophical frames, are consistent with the world views of settler colonial societies, and have authorized occupations, genocide, and other forms of state violence. Non-teleological resistance theories do not fetishize progress, but understand that change happens in ways that make new, old-but-returned, and previously unseen possibilities available at each juncture (see Deleuze and Guattari [2003] on flows and segmentarities, and Tuck [2009] on indigenous theories of change, including sovereignty, contention, balance, and relationship). Non-teleological theories of resistance are messy, and the endgame of such resistance is unfixed and always taking shape. (Tuck & Yang, 2011, p. 522)

We wonder whether we can imagine haunting as a form of messy resistance, a disruption of dominant narratives, and a way to linger with that which we long for.

Longing

van Dooren (2015) offered an urgent provocation in his call to think about what “caring practices might enable hopes for the future?” (p. 3). After exposing the limitations and possibilities of caring practices aimed at holding near extinct snail species in captivity so that they can be in the world just a little longer, van Dooren urged readers to think critically about how particular approaches to care sustain a certain kind of vision for the future. The argument is not that care for dying snails is futile, instead a sort of temporality of belonging within the palliative care of hospicing is enacted. This care is “world making that enhances the lives of others,” however fleeting, in a global “time of extinctions” where it is no longer possible to disavow that “we are living amidst the ruination of others” (Bird Rose, 2011, p. 51). Longing, as we conceptualize it, queers temporality and relationality as it mixes nostalgia with futurism and desire with mourning just as it demands presence and action now. Longing is situated and durative; it is “love and extinction” (Bird Rose, 2011). We wonder: What might be opened up if we think care through/beyond regulatory frameworks? With the hauntology of desire? Against patriarchal modes of “protection,” reproduction and production. What might rematriation of ECEC make possible? What if we slow down with snails for a moment and pay more attention to what it is that we are specifically hoping for and working towards?

In van Dooren’s (2020) words our desire to “reconstruct the not-[yet]-seen” children, educators’ and caregiver’s paths is “relentless” transforming evidence-based reporting into documentation practices that tell ethical stories of “the becomings of the unknown and the unrecognizable.” Musing on the weight of our collective responsibility to care for humans and things, Ingold (2017) offered the concept of “longing” as an impulse, a drive, a life that is “running ahead of itself” (p. 23)—not unlike the snails’ feelers. Longing is also a relation with past (remembering) and the future (imagining) worlds. Yet, as Ingold (2017) further clarified, “To imagine is not to project the future, as a state of affairs distinct from the present. It is rather to catch a life that, in its hopes and dreams, has a way of running ahead of its moorings in the material world” (p. 21). Longing resonates with Rosi Braidotti’s (2020, p. 468) rejection of the notion of a transcendental life, thus affirming our co-construction of one’s life alongside others as a collective that converges together, but that does not represent us as “one and the same” (p. 465).

Slow Activism

In this paper, we have been drawing in and issuing-forth lines of slow revolution that engage with desiring, hospicing, haunting, and longing. We’ve taken time to think-with snails and slowness, which aims to resist productionism, and, instead, enacts a slow ethics, a politics, a practice, and an imaginary of speculative care (Puig de la Bellacasa, 2017). Productionism involves reducing children, educators, and ECEC as childcare to mere resources, for example, as necessary conditions to re-start and maintain the economy, posing the risk for ECEC of becoming that last snail—extinct, in boxed categories (van Dooren, 2015). On the other hand, speculative care is a “commitment to seek what other worlds could be in the making through caring while staying with the trouble of our own complicities and implications” (Puig de la Bellacasa, 2017, p. 204). Speculative care is also about what Adrienne Rich (1993) called “the first revolutionary question...What if--?--” (pp. 241–242).

Slow does not mean inaction. In our desire-based framework, slow and activism co-exist. In an attempt to move beyond liberal politics that depend on the capture of social power, Liboiron et al. (2018) evoked the notion of slow activism. Slow activism challenges the myth of a single hero and big moments that change national policy. Slow activism engages in the mundane, everyday chores of care, as it shifts our attention from achievement to ethics. While slow activism may not be immediately effective, it may diversify politics and expand concepts of agency and action to include stories of caring otherwise. As Liboiron and colleagues (2018) explained,

Slow activism does not literally mean actions are sluggish (though they can be), but that the effects of action are slow to appear or to trace. ... Slow activism does not have to be immediately affective or effective, premised on an anticipated result. It can just be good. (p. 341)

As we slowed down to think about a slow ECEC revolution, as we undertook this important slow work of listening to the webinar recordings and video capsules, pausing every few minutes to take notes, we were impatient, so used to the fast-paced demands of emails imposing immediate responses, and to cutting corners that taking the time to listen and to think felt uncomfortable. We, as researchers, along with ECEC and the rest of our communities, are subjected to neoliberal demands to be productive. Going deep, staying with the trouble, being so-called unproductive is unfamiliar and feels unnatural. What lies beyond servicing? Or might service be reconceptualized and infused with ethical obligation and/as care for the world? We spent days slowly listening, taking notes, reflecting, feeling guilty, uneasy, at times, for ignoring emails and pressing administrative tasks. Then we met as a group to discuss, question, propose new readings, and laugh, learning from and with one another, weaving relationships, slowly imagining a revolution. Working slowly is a privilege and a pleasure, and led to the creation of something we hope can be of use to others in the field. We hope that in slowly reading and thinking about the ideas we share here, readers will imagine other ways of making change happen in their own ECEC contexts, paying attention to the small moments of unfolding caring relations and storying unknown worlds.

References

Akbari, E. (2021, June 3). New cross-Canada research highlights an early childhood educator recruitment crisis. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/new-cross-canada-research-highlights-an-early-childhood-educator-recruitment-crisis-160968

Andreotti, V. D. O., Stein, S., Ahenakew, C., & Hunt, D. (2015). Mapping interpretations of decolonization in the context of higher education. Decolonization: Indigeneity Education & Society, 4(1), 21–40.

Atkinson Centre. (2020). The early childhood education report 2000. Atkinson Centre, University of Toronto. https://ecereport.ca/en/

Bird Rose, D. (2011). Wild dog dreaming: Love and extinction. University of Virginia Press.

Bird Rose, D. (2013). Slowly~ writing into the Anthropocene. TEXT, 20, 1–14.

Bonetti, S. (2020, June 17). Making the early years workforce more sustainable after COVID-19. Nuffield Foundation: Opinion. https://www.nuffieldfoundation.org/news/opinion/making-early-years-workforce-more-sustainable-after-covid-19

Braidotti, R. (2020). “We” are in this together, but we are not one and the same. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry, 17(4), 465–469. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-020-10017-8

Brand, D. (2020, July 4). Dionne Brand: On narrative, reckoning and the calculus of living and dying. Toronto Star. https://www.thestar.com/entertainment/books/2020/07/04/dionne-brand-on-narrative-reckoning-and-the-calculus-of-living-and-dying.html

Cameron, C., & Moss, P. (2020). Transforming early childhood education: Towards a democratic education. UCL Press.

Clark, A. (2022, August 26). Time for play: Claiming back time in early childhood education and care [Keynote presentation]. The 31st European Early Childhood Education Research (EECRA) Association Conference, Glasgow, Scotland.

Friendly, M., & Ballantyne, M. (2020, March 24). COVID-19 crisis shows us childcare is always an essential service. Policy Options. Institute for Research on Public Policy. https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/march-2020/covid-19-crisis-shows-us-childcare-is-always-an-essential-service/

Gordon, A. F. (1997). Ghostly matters: Haunting and the sociological imagination. University of Minnesota Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctttt4hp

Government of Canada (2018). Indigenous early learning and child care framework. Employment and Social Development Canada. http://epe.lac-bac.gc.ca/100/201/301/weekly_acquisitions_list-ef/2018/18-39/publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2018/edsc-esdc/Em20-97-2018-eng.pdf

Government of Canada (2021). Budget 2021: A Canada-wide early learning and child care plan. Department of Finance, Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/news/2021/04/budget-2021-a-canada-wide-early-learning-and-child-care-plan.html

Haraway, D. (2004). The Haraway reader. Monoskop.

Haraway, D. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Duke.

Hartman, Y., & Darab, S. (2012). A call for slow scholarship: A case study on the intensification of academic life and its implications for pedagogy. Review of Education, Pedagogy & Cultural Studies, 34(1-2), 49–60.

Hoyos Vivas, L. M. (2020). Honouring cultural differences in early childhood education and care: Participatory research with a Colombian Embera Chamí Indigenous community [Doctoral dissertation, Concordia University]. Spectrum Research Repository. https://spectrum.library.concordia.ca/id/eprint/986649/

Hoyos Vivas, L. M., Massing, C., & Pighini, M. (2021). Indigenous and international inspirations: Sharing De Cero A Siempre (From Zero to Forever). https://ecenarratives.opened.ca/indigenous-and-international-narratives

Ingold, T. (2015). Lines: A brief history. Routledge.

Ingold, T. (2017). On human correspondence. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 23(1), 9–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9655.12541

Kind, S., Shayan, T., & Cameron, C. (2019). Lingering in artistic spaces: Becoming attuned to children’s processes and perspectives through the early childhood studio. In C. Patterson & L. Kocher (Eds.), Pedagogies for children’s perspectives (pp. 67–80). Routledge.

Klukas, J. (2021, June 9). Canada has child-care problems—but we can solve them. The Tyee. https://thetyee.ca/Analysis/2021/06/09/Canada-Has-Child-Care-Problems-We-Can-Solve-Them/

Liboiron, M., Tironi, M., & Calvillo, N. (2018). Toxic politics: Acting in a permanently polluted world. Social Studies of Science, 48(3), 331–349. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312718783087

Machado de Oliveira, V. (2021). Hospicing modernity: Facing humanity's wrongs and the implications for social activism. North Atlantic Books.

Maeers, E., Hewes, J., Lysack, M., & Whitty, P. (2022). Pandemic-provoked “throwntogetherness”: Narrating change in ECEC in Canada. in education, 28(1b), 21–40.

Massing, C., Lirette, P., & Paquette, A. (2022). “With fear in our bellies”: A pan-Canadian conversation with early childhood educators. in education, 28(1b), 41–61.

Moss, P. (2006). Early childhood institutions as loci of ethical and political practice. International Journal of Educational Policy Research and Practice: Reconceptualizing Childhood Studies, 7, 127–136.

Moss, P. (2010). We cannot continue as we are: The educator in an education for survival. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 11(1), 8–19. https://doi.org/10.2304/ciec.2010.11.1.8

Moss, P., & Cameron, C. (2020, September 1). In focus: Early childhood education—time for an ECE revolution. Nursery World. https://www.nurseryworld.co.uk/news/article/in-focus-early-childhood-education-time-for-an-ece-revolution

Pasolli, L. (2021, October 7). Creating universal child care from the ground up: The legacy of Toronto's grassroots child care advocacy. The Childcare Resource and Research Unit. https://childcarecanada.org/blog/creating-universal-child-care-ground-legacy-torontos-grassroots-child-care-advocacy

Price, M. (2021, September 8). Why do snails sometimes leave dotted trails? New Scientist. https://www.newscientist.com/lastword/mg25133512-700-why-do-snails-sometimes-leave-dotted-trails/

Puig de la Bellacasa, M. (2017). Matters of care: Speculative ethics in more than human worlds. University of Minnesota Press.

Rich, A. (1993). What is found there: Notebooks on poetry and politics. W.W. Norton.

Rinaldi, C. (2006). In dialogue with Reggio Emilia: Listening researching and learning. Routledge.

Slow Science Academy. (2010). The Slow Science Academy manifesto. http://slow-science.org/

Stein, S., & Andreotti, V. D. O. (2017). Higher education and the modern/colonial global imaginary. Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies, 17(3), 173–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532708616672673

Stengers, I. (2005). A cosmopolitical proposal. In B. Latour & P. Weibel (Eds.), Making things public: Atmospheres of democracy (pp. 994–1003). MIT Press.

Stengers, I. (2018). Another science is possible: A manifesto for slow science (Trans. S. Muecke). Polity.

Tsing, A. (2015). The mushroom at the end of the world: On the possibility of life in capitalist ruins. Princeton University Press.

Tsing, A., Swanson, H. A., Gan, E., & Bubandt, N. (Eds.). (2017). Arts of living on a damaged planet: Ghosts and monsters of the Anthropocene. Minnesota Press.

Tuck, E. (2009). Suspending damage: A letter to communities. Harvard Educational Review, 79(3), 409–427. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.79.3.n0016675661t3n15 Tuck, E. (2018). Biting the university that feeds us. In M. Spooner & J. McNinch (Eds.), Dissent knowledge in higher education (pp. 149–167). University of Regina Press.

Tuck, E., & Ree, C. (2013). A glossary of haunting. In S. Holman Jones, T. E. Adams, & C.

Ellis (Eds.), Handbook of autoethnography (pp. 639–658). Left Coast Press.

Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2011). Youth resistance revisited: New theories of youth negotiations of educational injustices. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 24(5), 521–530. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2011.600274

Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor., 1(1), 1–40.

van Dooren, T. (2015). The last snail: Loss, hope and care for the future. In A. S. Springer & E. Turpin (Eds.), Land & animal & nonanimal (pp. 1–14). Haus der Kulturen der Wel. https://www.thomvandooren.org/essays/

van Dooren, T. (2016). The last snail: Loss, hope and care for the future. In J. Newell, L. Robin, & K. Wehner (Eds.), Curating the future (pp. 169–176). Routledge.

van Dooren, T. (2019, August 15). Hospice earth. Overland. https://overland.org.au/2019/08/hospice-earth/

UMassHistory. (2020, October 23). Thom van Dooren: The world in a shell [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/fcl9-Njn-sA

van Dooren, T. (2021, 26 January). Mourning as care in the snail ark. Society for Cultural Anthropology: Editor’s Forum. https://culanth.org/fieldsights/mourning-as-care-in-the-snail-ark

Endnotes

[2] See https://ecenarratives.opened.ca/ for further details and to access recordings of the events.

[3] For all thirteen agreements, see https://www.canada.ca/en/early-learning-child-care-agreement/agreements-provinces-territories.html