Pandemic-Provoked

“Throwntogetherness”: Narrating Change in ECEC in Canada

Esther

Maeers, University of Regina

Jane

Hewes, Thompson Rivers University

Monica

Lysack, Sheridan College

Pam

Whitty, University of New Brunswick

Authors’

Note

Pam

Whitty https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0820-2099

This

research was funded through a Social Sciences and Humanities Research

Council (SSHRC) Connections grant.

Correspondence

concerning this article should be addressed to

Esther.Maeers@uregina.ca

_____________________

“A

Time to Organize, Not to Agonize” (Braidotti, 2020, p. 467)

We

are meeting over Zoom—a now very familiar space and practice

that was born of the urgency and intensity of the COVID-19 lockdown.

The particular 2-year ECE

Narratives Project

highlighted in this article began in April 2020, just at the moment

when the response to COVID-19 provoked dramatic changes to the way

most of us work and live in the world. Given the pervasiveness of the

lockdowns, we moved our planning and research meetings online and our

in-person events from physical meeting places to virtual meeting

spaces. In these virtual spaces, we have had hundreds of

conversations trying to make sense of the uncertainties and

inequities in early childhood education and care (ECEC)[1]

made particularly visible throughout the lockdown. We have shown up

weekly—10 framed faces across four time zones—we have

virtually entered each other’s homes—grateful for the

project and each other. Within the context of our lives and this

work, we are advocates, activists, educators, and researchers engaged

in various roles with responsibilities that are often entangled and

mutually informative. We, too, were experiencing the crisis. Our

conversations over Zoom became a life line. And given the sudden and

unexpected focus upon childcare within the pandemic, we were

determined to better understand—in this moment of incredible

disruption—how change in ECEC has happened and how we might

quickly contribute to this national and very public conversation.

This

article emerges, with hope, from within the context of a Canada-wide

Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) Connections

grant. We four, Esther, Jane, Monica, and Pam, part of the group of

10 framed faces, are working within the ECE

Narratives Project

(https://ecenarratives.opened.ca/).

Our primary research focus is on change in ECEC in Canada. In the

context of this focus, we ask: What are the narratives that create,

describe, and perpetuate change; how do they work; and what do, or

might, particular narratives offer to the present and future

possibilities for ECEC within Canada? As we began the project, our

collective sense was that there were and have been many narratives

aiming to influence change in ECEC in Canada, and that change has

happened and continues to happen. Each of us has participated in

change in different ways, changes that have made differences in the

present while offering possibilities for future practice and policy.

Collectively we have also experienced change in ECEC in Canada as a

never-ending story (Mahon, 2000; Pasolli, 2019), a what now/where to

now story, one that Kate Bezanson (2018) characterized as the

government of Canada’s stop-start relationship to the field of

early learning (p. 191). In this article we narrate personal stories

of change in ECEC as we experienced them within the ECE

Narratives Project.

In

our desire to think about and with narratives of change within ECEC,

our ECE

Narratives research

group was able to create conditions and invitations for national and

international conversations. Our approach to this research has been

to take up conversations as bricolage with conversations acting as

point

of entry texts (POET)

(Berry, 2004, p. 108). Collectively and individually, we narrate

change as we experienced it in conversations with people in ECEC:

policy advocates, educators, and scholars within Canada and

internationally. To facilitate these conversations, and over the

course of our two-year project, the ECE

Narratives Project

organized two webinars, the first in June 2020, a full year before

the federal commitment of $30 billion dollars for early learning and

child care (Tasker, 2021). At that time, we held conversations with

ECEC policy influencers—some well-known and some who had been

working unseen for decades. In our second webinar, in November 2020,

we held conversations with ECEC educators who were thoughtfully,

persistently, and creatively staying focused on their relations with

children and their families as childcare centres strove to stay open

or as they re-opened. In conjunction with the webinar conversations,

ECEC educators from across the country shared visual representations

of their experiences animating the actions they were taking to stay

connected with families, children, and community in spite of spatial

and temporal shifts created by COVID-19 to the provision of care

(https://ecenarratives.opened.ca/webinar-collages/).

Our third event occurred across 2021–2022, when we had

conversations with international and Indigenous policy makers and

educators. From these conversations, we created videos and research

briefs bringing together insights and possibilities for changes to

ECEC in Canada.

Moving

Forward With Uncertainty

To

learn about change in ECEC through conversations as bricolage, and in

the context of this paper, we focus upon discourses and related

narratives we heard within the first webinar. What are these

narratives and what are they telling us about change in ECEC? What

might we imagine for our collective futures? Our first webinar, held

on June 10th, 2020, was entitled: Moving

Forward With Uncertainty: The Pandemic as Déclencheur* for a

Competent ECEC System Across Canada/ Aller de l’avant dans

l’incertitude : La pandémie comme catalyseur* de

transformation d’un système plus adapté

d’éducation à la petite enfance à travers

le Canada (https://ecenarratives.opened.ca/policy-narratives/).

For

this webinar, we brought together policy experts for a round table

discussion on current ECEC realities and initiatives across Canada.

The focus of the webinar was to illuminate and respond to the impact

of the changing perceptions and realities in childcare as COVID-19

affected the lives of children, families, and society overall. It was

our response to events unfolding immediately around us. Collectively,

we had knowledge, resources, and networks to draw on. We were ready

to act. Specifically, Monica was deeply engaged at the political

level in ongoing advocacy work/responses to the crisis and she

invited individuals with whom she was working to share their

knowledge and insights. The webinar conversation came together very

quickly. In making sense of how this happened, we experienced what

Doreen Massey (2005) described as the “throwntogetherness”

of place, “an ever-shifting constellation of trajectories,”

always and crucially “the combination of order and chance”

(p. 151). Through planning on a national scale, we had a SSHRC grant,

and although not by chance, but certainly unexpectedly, we were in a

pandemic. Thus, at the beginning of the pandemic, we had collectively

and fortuitously created a place where we could, as Rosi Braidotti

(2020) suggested, “organize rather than agonize” (p. 3).

In

the first webinar, two groups of panelists took part: the first panel

was composed of well-known childcare speakers from national childcare

organizations, while the second was composed of speakers, lesser

known, whose work was largely behind the scenes, out of sight,

underground—people whose focus was to bridge the work of the

advocates with that of policy makers and politicians. We were only 3

months into the pandemic, and a palpable sense of urgency permeated

the webinar discussion. There was no doubt that ECEC in Canada was in

crisis. We hoped that governments and policy makers might share our

sense of urgency in this moment, and be compelled to act. We were

energized and inspired. We found ourselves in the position of being

able to do something—to bring people together at an auspicious

moment for a public conversation. To our surprise, the event drew

over 400 registrants. For us, this moment in time and space animated

Massey’s (2005) notion of the significance of the public place

and the “politics of the event of place” (p. 149): the

pandemic politics of Canada and the newly and unexpectedly public

space of the virtual.

Unangax̂

scholar Eve Tuck (2018b) theorized that when we are thinking about

how change happens, there is no single best answer. Tuck suggested

that to gain an understanding of change we need to move into the

messiness of conversations, to take seriously the practice of

conversation within all its “mired contestations” (Tuck,

2018b, 6:08). What we learned in these mired contestations is that

when narrating change there is no single best answer, no single

narrative; rather, narrating change in ECEC in Canada reverberated

with Veronica Pacini-Ketchabaw’s (2010) theorizing of “flows,

rhythms, and intensities'' (p. xii); moving into the messiness of

conversation is “inventive” rather than “predictive”

(p. xii). As we discussed possibilities arising from our

long-standing and ongoing conversations, we were engaged with

re-conceptualist ECEC scholarship (Ashton, 2015; Iannacci &

Whitty, 2009; Moss, 2018; Pacini-Ketchabaw & Pence, 2005;). In

the introduction of Be Realistic, Demand the Impossible: A Memoir

of Work in Childcare and Education by Helen Penn (2019), Michel

Vandenbroeck, drawing on Foucault, described the purpose of

contesting early childhood as working “to interrogate such

discourses that are presented as evident, to shake up habits, ways of

thinking, familiarities and to re-problematize these” (p. vi).

We considered hegemonic discourses and those less dominant. As Peter

Moss (2018) reminds us, a dominant discourse “never manages

totally to silence other discourses or stories. … These

stories may be unheard by power and consigned to the margins, for the

time being at least, but they are out there to be heard by those who

listen” (p. 7). We heard many stories, and as we listened and

re-listened to these stories, we could hear stories narrating change.

Narrating

Change

We

intend this next section to be read as a bricolage of ideas from our

conversations—particular moments in time emanating from our

first webinar that are echoing, reverberating, repeating, haunting.

In effect, these conversational moments act as point of entry texts

generating the bricolage (Berry, 2004, p. 108). Collectively created

through our conversations, we now share our individual narratives,

narrating stories of change, recognizing their intersecting, partial,

and resonating natures. Monica animates “strategic pester

power,” its persistence over time, in numerous spaces, and with

and by a variety of people. Pam considers the shifting context

of Indigenous knowledges and ways of being as they are

re-materialized in pedagogical and literary texts by Indigenous

peoples. Jane takes a closer look at ECEC pedagogy as an

alternative—and potentially transformative—narrative of

change, unfolding in and through Canadian ECEC curriculum frameworks.

Esther describes how an ECEC educator co-creates new texts with

children, creating renewed relationships to families, community, and

land, providing hope in a time of great uncertainty.

Monica:

Strategic Pester Power

I

am a Treaty Four person, second generation Canadian, living and

working with First Nations and Metis communities in Saskatchewan and

Ontario. I am grateful and humbled by the wisdom and respect for the

traditional knowledge of the Metis Nation and many First Nations,

shared with me by elders, educators, and students.

Two

years have passed since ECE Narratives’ first policy

webinar; 2 years that changed our worlds. Two years since childcare

was deemed as an essential service in the face of the pandemic, and 2

years since the 50-year struggle in childcare was brought to

fruition. On April 19, 2021, Canada’s first female finance

minister Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland announced a $30

billion dollar commitment to creating a Canada-wide early learning

and childcare program.

It

was just over 50 years ago that the Royal Commission on the Status

of Women in Canada (Bird et al., 1970) called for national

publicly funded childcare, the ramp to women’s equality. The

principal rationale was women’s equality and access to the

workforce to contribute economically. In subsequent decades, federal

governments, both Liberal and Conservative, have offered various

rationales, and promises for childcare and yet failed to deliver

(Friendly & Prentice, 2009). For the most part, childcare in

Canada has survived as a private service delivered within a market

model system (Beach & Ferns, 2015). While several countries

belonging to the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development

(OECD) have established stable, universal, and public ECEC systems,

Canada has not. As I think about my involvement with childcare, over

40 years as an early childhood educator, director, advocate, and

researcher, and the multiple rationales for public investment in

childcare, I can see that we are trapped—trying to find the one

“right” narrative—the narrative that would compel

the government to invest. If only we could find it. We were obsessed.

WE needed THEM to do something. Like Penn (2019), “I thought of

myself as someone without power or influence or connections”

(p. 33).

Penn

(2011), who served as rapporteur for Canada’s participation in

Starting Strong II (OECD, 2006) provided a summary and

analysis of multiple rationales that drive governments to implement

ECEC policy. She asserted that “sticky policies” and

their rationales are rooted in countries’ histories, changing

contexts, and public opinion. To open up the discussion of

rationales, Penn (2011) suggested that “the job of academics

and intellectuals—and students—is to step back a little

and analyze policies and their underpinning rationales, to be

skeptical” (p. 28). Our challenge is to take up Foucault’s

suggestion to interrogate, disrupt, and re-problematize dominant

discourses (Penn, 2019). In the pandemic, Canada’s rationale

for investment highlighted the dominant discourses of economic

returns and women’s equality which economist Armine Yalnizyan

(2020) described as the “she-cession.” Yalnizyan asserted

that women were disproportionately affected financially by the

pandemic and proposed that a Canada-wide early learning and childcare

system would mitigate the negative impact and support women’s

equality.

As

part of our research, we collected ECEC media narratives, which

included: ECEC as an essential service for the economy and for women

re-entering the workforce; ECEC as necessary for child development;

and articles on quality care, education, pedagogy, and practice. The

dominating media discourse of childcare as an essential service—for

essential health care staff—was a critical one which had the

ironic effect of silencing or obscuring other narratives such as

those being lived and told by educators. For example, early childhood

educators forced back to work during the lockdown were expected to

provide warm, loving care while maintaining social distancing between

adults and children as well as between very young children; they were

required to meet enhanced health and safety requirements without

support for additional staffing or appropriate personal protective

equipment (PPE). In the first webinar, we heard from more than one

speaker that children’s experience of lockdown childcare held

new stories for families about the value of childcare for their

children. These narratives were largely missing in the media.

In

the first webinar, the Honourable Myriam Monsef, minister for women

and gender equality, was invited to bring greetings. In her remarks,

Minister Monsef thanked participants for mobilizing, for

advocating, for “bringing us along with you … please

don’t stop” (Monsef, 2020, 7:20–8:19). This makes

me think about the “us” and the “them.” Who

is “them” and who is “us”? Often, we

construct women in government as other than “us.” Are we

putting up false barriers? Getting in our own way? In a recent

publication, Joanne Lehrer and I (Whitty et al., 2020) reflected on

the involvement of several women politicians who were involved in

childcare policy issues in Ontario and Quebec. We noted that

politicians, too, worked within and against their own parties,

sometimes traversing lines. I was beginning to realize that it wasn’t

about us and them. As Braidotti (2020) wrote, “WE are in this

together, but we are not one and the same” (p. 1).

The

“we” in our first webinar included several well-known

spokespeople, for example, Martha Friendly, Margo Greenwood, Don

Giesbrecht, and Morna Ballantyne. There were also panelists who have

worked behind the scenes, quietly and invisibly. One panelist spoke

about the informal “mommy network” amongst journalists,

who prioritized column space for pro-childcare reporting. Panelists

were asked to address questions such as the following:

Early

childhood education and care is a high-profile issue right now, can

you share your views about why ECEC is in the spotlight?

Why

has it been so difficult to advance a universal childcare system?

How

is Indigenous ECEC different?

How

has the world changed and what does that mean for childcare?

Are

there new arguments emerging now to support a Canada-wide universal

public childcare system?

In

Conflictual and Cooperative Childcare Politics in Canada,

Rachel Langford, Susan Prentice, Brooke Richardson, and Patrizia

Albanese (2016) analyzed and compared relationships between advocates

and both Liberal and Conservative governments when a national

childcare program was being proposed. They identified co-operative

relationships, conflictual relationships—and at times,

conflictual—co-operation. Thinking with these ideas, I

considered how they might help to explain why we have stalled, time

and time again; what impedes our progress? Is perfection the enemy of

good? Conversation in the webinar circled around whether it was

possible for multiple narratives to come together in a single

Canada-wide childcare system that jump-starts an economy ravaged by

the pandemic, and addresses equality for women and children’s

well-being in the present, as well as their education and care. We

stall on this conundrum, which Kate Bezanson, Andrew Bevan, and I

(2021) described as “complexity inertia.” We suggested,

Just

because something is complex doesn’t mean it’s

impossible. Rather, it compels an approach that bypasses

tried-and-failed, ideological or non-system-building models…

There are no shortcuts in system-building. (Bezanson, Bevan, &

Lysack, 2021, n.p.)

What

was it that finally compelled this government to deliver a

Canada-wide early learning and care program? The “strategic

pester power” of advocates was identified by Honourable Carolyn

Bennett (personal communication, April, 19, 2021), a long-time

childcare advocate who worked tirelessly within the Liberal party and

cabinet, along with other female ministers, to deliver on the

long-awaited national childcare program. In the moment, multiple

narratives from multiple sources converged. With a grand-scale

financial commitment and the political will expressed so clearly in

the budget announcement, the new challenge becomes, how do we build a

childcare system? At a recent national symposium on building the

national system, the Honourable Karina Gould (2022), minister of

families, children, and social development, challenged those in the

room and advocates across the country to shift how we work,

emphasizing, “It is different being an advocate on the outside

than it is being a builder on the inside … It doesn’t

mean don’t call us out, that is your job—but how can we

be constructive? This is an important moment ...We cannot build that

system without each and every one of you.” The question of who

is “we” continues to resonate.

Pam:

“There has Never Been Such a Framework for Our Children and Our

Families.”

I

live and work on the east coast of Canada in Wolastoqiyik territory

in what is now called New Brunswick. Wabanaki families have lived

here for thousands upon thousands of years. My mother’s and

father’s families have lived here for just over 200 years.

Although Peace and Friendship Treaties were signed by the Crown with

the Wabanaki Peoples between 1725 and 1779, many settlers, including

myself, are just coming to understand our responsibilities as Treaty

People. Cree storyteller, writer, activist, trapper, and lawyer

Harold Johnson (2007) in Two Families: Treaties and Government,

wrote of his family and mine:

I

have become convinced that my family will not be freed from tyranny

until your family members free their minds from tyranny. Not until

the dominant culture ceases to assume that its structures are

natural, necessary and superior will it cease to impose its ideology

over my family. …My family's survival as Indians depends on

your families leaving us room to be Indians to be independent and

self-sufficient. (p. 121)

In

June 2020, Cree researcher Margo Greenwood, spoke at our first

webinar, Moving Forward With Uncertainty: The Pandemic as

Déclencheur. She spoke directly to the realities of

Canada’s colonialism, the historic and extensive harms done to

Indigenous families and children through imposed structures and

ideologies. Greenwood (2020), whose research focuses upon the

well-being and health of Indigenous children and families, made very

clear to the webinar participants, that colonial practices in Canada

have resulted in current-day realities where immediate and

intergenerational harms and trauma for children and families are

evident in ECEC politics, policies, and practices:

When

you consider our history and our current day realities of First

Nations, Inuit, and Metis Peoples in Canada, we cannot deny the

colonial reality of Canada nor the fact that the First Nations,

Inuit, and Metis Peoples have been marginalized in their own lands.

We cannot deny any longer that colonialism has always been and

continues to be about power and the insistence that some have power

at the expense of others. (7:09–7:39)

Tuck

(2018b), in her talk, “I Do Not Want to Haunt You, But I Will,”

named colonialism as a longstanding theory of change in what is now

called Canada, a theory that meets with change reluctantly. Tuck

(2009) proposed interrupting this colonial power with Indigenous

power, working against colonialism as “a flawed theory of

change” (p. 409), a theory that perpetuated(s) damage-centered

research, intended “to document peoples’ pain and

brokenness to hold those in power accountable for their oppression”

(p. 409). Tuck (2009) advocated for suspending damage and enacting

desire-based change, with “wisdom and hope” (p. 416), in

part through the recognition of the local knowledge, narratives, and

values carried by Indigenous People. She respectfully acknowledged

that although there was a need to expose “the uninhabitable and

inhumane” conditions which Indigenous Peoples continue to live

in, a new historical moment calls for a shift from damage-centered

research (Tuck, 2009, pp. 415–416). She suggested instead a

move towards narratives of desire—to seek the layers, the

complexity, the contradictions, the “not yet and not anymore”

(Tuck, 2009, p. 417).

Referring

specifically to the COVID-19 realities that once again “shone a

light” upon persistent inequities within childcare in

Indigenous communities, Greenwood (2020, 8:00) described the critical

development and place of the Indigenous Early Learning and Child

Care Framework (IELCCF) (Government of Canada, 2018),

pointing out that Canada is finally enacting a distinctions-based

approach in ECEC with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples

(FNIM). Specifically, Greenwood noted that the IELCCF

foregrounds the safety and happiness of children and

self-determination within and across nation-to-nation relationships.

It is a very different starting point than other early learning and

child care curriculum (ELCC) frameworks in Canada. Indigenous

knowledges, languages, and culture are at the heart of the FNIM

frameworks. Self-determination and children’s cultural

identities are centred. A distinctions-based approach, Greenwood

(2020) stressed, is unique in the history of Canada: “There has

never been such a framework for our children and our families”

(2:16–2:30). Greenwood’s haunting statement calls up

centuries of the damage that has been, while opening spaces for

enacting a more desired future. As Greenwood (2020) further noted,

“So our children are at the core of our nations and they are

its survival and ensures its continuity” (6:55).

In

May 2021, 1 year after listening to Greenwood speak in the first

webinar, and as we were preparing a presentation for a national

conference, we learned that the unmarked graves of 215 Indigenous

children were found at the Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc

community in the southern interior of what is now called British

Columbia. The locating of unmarked graves across Canada is a stark

reminder of the deep harms orchestrated against particular children,

families, and communities by colonial policies and practices that

created and maintained Indian Residential Schools from the 1830’s

until 1996. As of May 24, 2022, the National Centre for Truth and

Reconciliation Memorial Register has confirmed the names of 4130

children who died while attending Indian Residential Schools

(Supernant, 2022). Kisha Supernant explained that many families were

never notified of the deaths of their children; bodies of their

children were never sent home; and survivors who were children at the

time remember children who went missing, and in some cases these

survivors were responsible for digging graves of children who had

died. The immediate and intergenerational effects of this traumatic

policy are now highly visible within Canadian popular media. Many

settler Canadians are waking up to narratives of loss of children,

culture, language, spirituality, and community, narratives of loss

and lack, that Indigenous Peoples have been speaking to and about,

living with, re-telling, and resisting for a very long time.

In

her research with Indigenous life writings and epistolary texts,

Elise Couture-Grondin (2018), drawing from Braidotti’s concept

of affirmative ethics, took up the practice of affirmative readings,

which “follow a non-oppositional logic in which difference is

taken as incommensurable singularity, instead of conceiving of

Indigenous difference in a binary opposition to white settlers”

(p. 318). For Couture-Grondin (2018), affirmative readings, which

could also be applied to the creation and reading of Indigenous ELCC

frameworks, place the “ethical reach of a text” beyond

raising awareness or being educative, to the possibility of

transformation by “offering alternative views of relationships,

and by enacting different types of relationships in the literary

field in which readers can engage” (p. 323). There is a

possibility to engage with incommensurability, “in ways that

counter the mechanisms of cognitive imperialism and

appropriation/elimination” (Couture-Grondin, 2018, p. 321).

Affirmative

readings, a taking up of affirmative ethics can also be engaged as a

reading-response with picture books authored and illustrated by

Indigenous Peoples. Nicola Campbell (2005), in Shi-Shi-etko

places two stories side by side. In her one page austere black and

white preface, Campbell, a Nłeʔkepmx, Syilx, and Métis

author, living in British Columbia outlines the history and harms

caused by policies of residential schooling, asking the questions,

what would it mean to live without families, to live without

communities? The beautifully crafted, colour images by Kim LaFave

show the daily life of an Indigenous community in the four days prior

to Shi-shi-etko being taken from her family and community. These two

apparently incommensurable stories stand together in the book, the

Indigenous story justly taking up more time and space—being

told and heard in its own right.

Swampy

Cree author, David A. Robertson and Julie Flett (2016) of Cree Metis

descent, in When We Were Alone, tell a different kind of

double story, that of a young girl learning from her Nokum. Nokum

speaks to her granddaughter about how she and a friend lived through

their residential school days remembering and taking up cultural and

linguistic practices from home “when they were alone.”

Leanne Simpson (2018, as cited in Couture-Grondin, 2018) affirmed,

that with stories, Indigenous Peoples “pick up things where we

were forced to leave them behind, whether songs, dances, values or

philosophies and bring them into existence with the future”

(pp. 49–50)—which is what Nokum does in this story with

the conversation with her granddaughter, a conversation that can be

engaged with, witnessed, and learned from by all inhabitants of

Turtle Island.

Indigenous

texts, including Shi-shi-etko, When We Were Alone, and the

distinctions-based IELCCF, foreground different knowledges and

stories than colonially based ELCC frameworks and colonial picture

books. These Indigenous texts stand together, and are very different

from most of the texts I have read for most of my life. At the

moment, many Indigenous texts are written in English; thus, once

again I benefit from Indigenous knowledges at the cost of Indigenous

languages. My hope is that with the resurgence of Indigenous

languages, with the translation and production of more Indigenous

texts in Indigenous languages, and considering the foregrounding of

Indigenous languages in the IELCCF, a different Indigenous

future is materializing. Returning to Johnson (2007), perhaps in the

foreseeable future, my family will finally leave space for his family

“to be independent and self-sufficient” (p. 121).

Jane—ECEC

Pedagogy—The Beginning of a New Story

The

place I call home is on Treaty Six territory, where I grew up and

later raised my own family in amiskwaciy-wâskahikan, the

nehiyawewin (Cree) name for Beaver Hills House, now known as

Edmonton. I have fond childhood memories of playing in the bush on

the banks of the swift flowing kisiskâciwanisîpiy, until

recently known to me only as the North Saskatchewan River. Since

2016, I have been living and working on the traditional and unceded

territory of the Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc people in the

nation of Secwepemcúl’ecw, in the first place where the

presence of unmarked graves of children believed to be as young as 3

years of age who died while attending residential schools in Canada,

was confirmed in May 2021.

In

the spirit of story as theory, and conversation as bricolage, I will

look more closely and critically at ECEC pedagogy as an alternative

narrative of change, given momentum in Canada through the provincial

ELCC frameworks created in each of the 10 provinces, and most

recently a distinct First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Indigenous

Framework named above as the IELCCF (Government of Canada,

2018). ECEC pedagogy is a new story, with the potential to shape the

direction of change in this moment of possibility for ECEC in Canada.

I was initially inspired by a comment in the chat in the first

webinar from Iris Berger, one of our research team members:

What

if we move the narrative beyond ECEC as an “essential service”

for the economy, and focus on children, early childhood educators

(who are more than a workforce), the role of ECEC in community, and

the unique ECEC pedagogy? (Personal communication, June 10, 2020)

The

creation of ELCC frameworks in Canada followed the release of the

OECD review of ECEC (OECD, 2001; OECD, 2006) and the follow-up

analysis of pedagogical approaches by John Bennett (2005) who led the

OECD review, calling for pedagogical frameworks to be organized

around a statement of principles and values, broad overarching goals,

and pedagogical guidelines for reaching those goals. Like others on

our ECE

Narratives research

team, I became involved in creating a framework in my home province

at the time, leading the design of the participatory action research

that created Flight:

Alberta’s Early Learning and Care Framework

in

2018.[2]

Our

process in Alberta was critically and generously informed by the

Early Childhood Research and Development Team that created the New

Brunswick Curriculum Framework for Early Learning and Child

Care~English (NBCF~English) in 2007, one of the first in

Canada. Pam Whitty (2009) described the participation of over 1300

early childhood educators involved in creation of the NBCF~English

as a process of “reclaiming, reconstituting, and textualizing

conversations and conversational moments of pedagogical learning and

care from childcare educators” (p. 37). We followed a similar

path in Alberta, working with early childhood educators to document

stories of curriculum that was “already happening” as a

starting point for pedagogical conversations (Hewes et al., 2019).

Resources made available through the research project made it

possible for educators to talk with one another during their workday

about what they were doing and experiencing with children and

families, and what they wanted to do. The process of talking about

their pedagogy was challenging at first. Slowly, tentatively, and

occasionally powerfully, these conversations, the “stories the

players tell themselves about themselves” (Geertz, 1972)

nurtured educators’ identity, agency, confidence, and valuing

of their work. Anna Szylko (as cited in Hewes & Lirette, 2018),

one of the project pedagogical mentors, recognized, “Our staff

meetings will never be about ‘who left the lint in the dryer’

again.” Rebekah McCarron (as cited in Hewes et al., 2019), a

new early childhood educator, realized a change in her sense of

herself as an educator: “What I do does matter, and this

realization has forever changed me” p. 49). These were heady

times, when it sometimes felt like practice had leapt out ahead of

theory, leaving the research team behind in our “bumptiousness”

(Haraway, 2016, p. 1). We wrote and published and presented

collaboratively alongside educators about this story of change (Hewes

et al., 2019; Hewes et al., 2016; Makovichuk et al., 2017; Whitty et

al., 2018). As others have noted, the ELCC frameworks have been

helpful in moving thought and practice away from and beyond

developmentalism, and towards story as the starting point for

pedagogy.

Setting

aside for a moment my unapologetic joy at having played a small part

in such an uplifting initiative, I am reminded that we are still at

the beginning of the story of ECEC pedagogy in Canada. Critical

questions are surfacing about the representation of diversity,

inclusion, and difference in socio-pedagogic curriculum frameworks,

particularly in relationship to the positioning of Indigenous

pedagogies. The notion of incommensurability, in particular an

“ethics of incommensurability” (Tuck & Yang, 2012),

offers insight. In a critique of South African early childhood

policy, Norma Rudolph (2017) outlines how well-intentioned efforts to

address the poverty of Indigenous peoples by “adding on”

Indigenous content to ECE curricula have failed because they do not

address “fundamental issues of commensurability and hierarchies

of knowledge that silence Indigenous perspectives and ways of being

prevalent in different communities” (p. 95). Speaking to the

incommensurability of Indigenous and non-Indigenous world views, Eve

Tuck and K. Wayne Yang (2012) deepen our understanding, with their

description of an ethic of incommensurability “which recognizes

what is distinct," maintaining that Indigenous and colonial

worldviews cannot always be “aligned or allied” (p. 28).

Building on these ideas, Couture-Grondin (2018) wrote:

Incommensurability

1) insists on spaces of knowledge that cannot be appropriated; 2)

signals the impossibility of comparing and putting differences on a

single scale; and 3) accepts misunderstanding as a problem that does

not have to be resolved or reconciled. (p. 15)

Socio-pedagogic

frameworks offer an alternative to theme-based planning and

prescriptive curricula. In our efforts to enact a co-constructed,

locally and culturally situated, values-based pedagogy, we forget

that curricula do not exist in isolation and that all of us remain

“engulfed in neoliberal, and neocolonial thinking”

(Tesar, 2015, p. 192). In Troubling Settlerness in Early Childhood

Curriculum Development, Emily Ashton (2015) contended that “a

social pedagogical approach creates an air of comfort rather than

critique” (p. 93) and asked:

What

differences are irreducible? When might inclusion be best refused?

How might taking up incommensurability contest the taken for granted

assumptions underpinning inclusion and diversity rhetoric in early

childhood curricula? (p. 82)

These

are urgent and provocative questions for our pedagogy. We have an

opportunity as well as an obligation to act (Johnson, 2021). What

would it look like if we truly believed in Greenwood’s (2020)

vision that it is through children that a better world will be

achieved? What if we follow Ashton’s (2015) advice to “stay

with the trouble” (Haraway, 2016) of incommensurability as a

productive space, rather than trying to resolve differences? And to

document children’s struggles to make meaning of difference

(Ashton, 2015, p. 91)? What would taking up an ethic of

incommensurability look like in early childhood pedagogy?

Esther:

Finding Our Place in the Story, and the Story is Not Finished …

I

live and work on Treaty Four territory, within the Canadian prairies,

the ancestral lands of the nêhiyawak, Anihšināpēk,

Dakota, Lakota, and Nakota peoples, and the homeland of the

Métis/Michif Nation. My father’s side of the family

arrived as settlers from England and Holland and have been in Canada

for generations. My mother arrived in this country as a young teacher

from Scotland. I am a first generation Canadian on her side. I grew

up in the Northwest Territories amongst the Dene and Inuit peoples.

Western narratives were all that I learned as a young child. I

distinctly remember seeing brown faces looking out of windows on

separate buses headed to St. Patrick’s school. As an adult, I

now understand where they were going each day. At this moment, I live

less than 100 km from where Treaty Four was signed in 1874. As a

white settler, I am learning my place in this story.

During

the lockdown, when our project began and our first webinar was

quickly and intentionally organized, I found myself struggling with a

lack of childcare. At that moment in time, I was propelled into the

role of juggling parenting, homeschooling, scholarship, and teaching.

As my children were underfoot, the narrative of childcare being an

essential service rang true for me, but there is more to this story.

Feeling isolated in my own work, I saw that my children were

experiencing this as well. Their friends and educators were now faces

on a screen. Their interactions with people were from a distance,

strained, and tension filled. Relationships have changed for all of

us. Children’s connections to their ECEC friends, educators,

and spaces have been disrupted. However, disrupted relationships run

deeper than the pandemic. In Canada, our violent colonial history has

created and continues to create disrupted oppressive relationships

(Little Bear, 2000).

Writing

about the incommensurability of Indigenous and colonial worldviews as

a non-Indigenous person, Morgan Johnson (2021) argued that an ethic

of incommensurability calls on White settlers not to explain or try

to resolve differences or to be bystanders to the conversation, but

rather to stand aside, using their position of privilege to open a

space for listening to Indigenous worldviews as distinct. Johnson

(2021) went on to explain that White settlers are obligated through

an ethic of incommensurability to understand who we are in the story

of settler colonization, “locating ourselves within a narrative

without undermining the ontologically distinct experience of the

other” (p. 42) because “we are all part of the story of

destruction and/or theft of land, but we have to understand who we

are in that story. Some of us may be victims and some may be

beneficiaries, but we are all part of the story” (p. 46). What

does this mean as we rebuild relationships, as we work towards truth

and reconciliation, and as we create a national ECEC system across

Canada? The pandemic has perhaps provided an opportunity to move

forward differently, and not return back to the way things were

(Henderson & Little Bear, 2021).

It

has now been over 2 years since we experienced global lockdowns;

however, we continue to struggle with the ongoing impacts from the

pandemic. As we emerge from this collective experience and with the

federal announcement of $30 billion dollars for the ECEC sector,

there is an added motivation to move forward intentionally and

collectively. Braidotti (2020) pointed out that there is a need “to

start by questioning who ‘we’ might be to begin with”

(p. 467). With the notion of ethics of incommensurability and who we

are in the story as a starting place, I share a profound experience

in one ECEC program, in which children and adults grapple with who we

are in the story of the land and how we shall live in relationship to

one another.

It

was the last day of school. My son, his kindergarten teacher, and his

classmates were preparing to share their land acknowledgement during

a ceremony for the grand opening of their Food Forest a co-created

garden project. A permaculture expert helped with the preparation of

the soil. A grandfather taught them how to plant tobacco in a good

way. A Cree teacher helped name their Food Forest. The educator

explained that she attended professional development courses to learn

about local plants, stating that "when I saw some buffalo

berries and sea buckthorn growing by the Creek, I knew we could grow

those" (personal communication, December, 5th, 2022). The

children worked with dirt and seeds, plants and water. The creation

of this garden took many months. The garden was full of edible plants

that the children and their teacher had learned to care for; plants

that would thrive in this particular place, had been carefully

chosen. There was excitement in the air, as this was one of the first

face-to-face events that the school had held since the pandemic

began. Smiling maskless faces were everywhere; being outdoors allowed

a sense of freedom from the safety protocols that everyone had become

accustomed to. Parents and family members were chatting and mingling,

reconnecting or meeting for the first time. The children lined up in

front of their garden, a beautiful painted mural behind them, a

co-created project in which every student in the school had

contributed. The ceremony began as families looked on, every child

participating, hands and bodies fully engaged with actions and words;

words that traveled through their bodies as they moved their arms in

unison, speaking to each other, the earth, and their families. The

teacher, her colleagues, and the children had co-created text,

illustrations, and actions for their land acknowledgement. This was

an ongoing process intended to be meaningful and accessible to the

youngest children in the school. Each afternoon the children

practiced the words and actions. Each day the children and adults

lived out these phrases as they walked in nature, planted and cared

for their garden, learned Cree words and phrases, experienced the

story of the land, and walked and learned alongside Indigenous Elders

and community members. The children were given space and time to

experience and express their relationships to land, humans, and

nature.

The

following land acknowledgement book is being shared with permission

from the teacher. All the words have been included as co-created by

the children and adults. However, only a few of the beautiful

illustrations are being shared where appropriate.

|

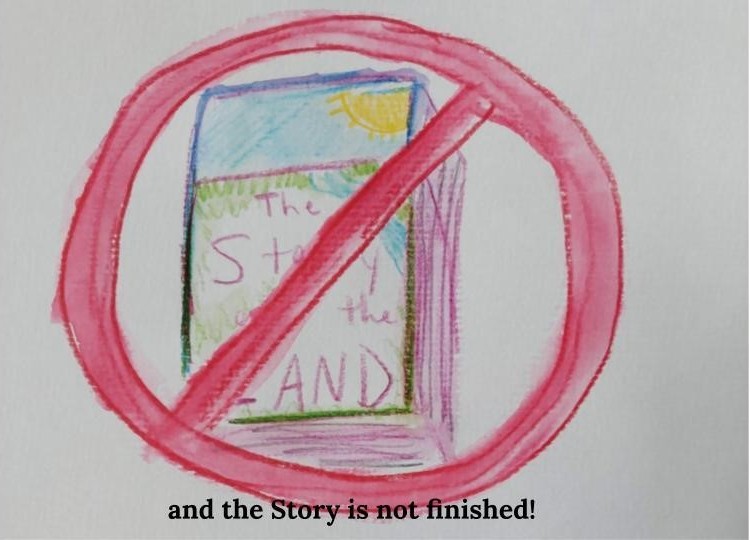

Figure

1

Land

Acknowledgement Book Cover

|

|

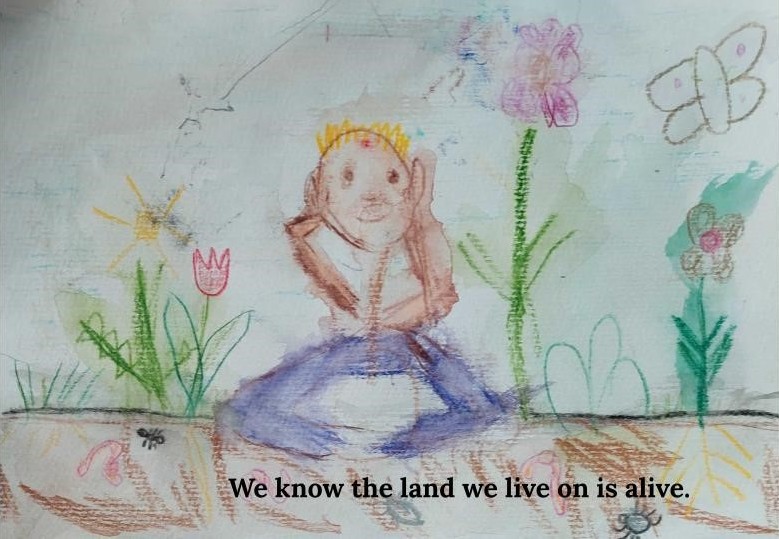

Figure

2

We

Know the Land We Live On is Alive

|

|

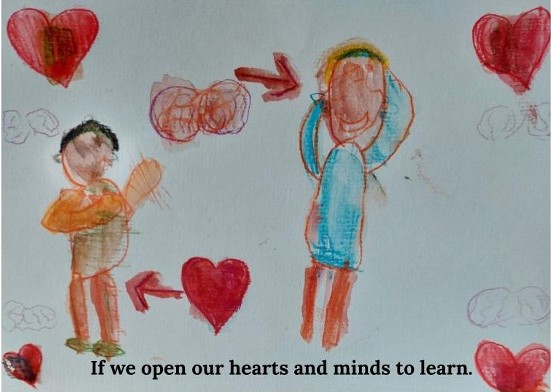

Figure

3

If

We Open Our Hearts and Minds to Learn

Note.

The text reads: “Mother Earth and the first land protectors

have stories and teachings to share with us, if we open our hearts

and our minds to learn. We take care of this place alongside our

relatives the nêhiyawak, Anihšināpēk,

Dakota, Lakota, and Nakota Nations and later, the Métis,

settlers and then newcomers. Together, we are Treaty Four People.”

|

|

Figure

4

We

Are All Part of the Story of the Land

Note.

The text reads: “That means that together, we are part of a

living promise to protect Mother Earth along with the water, the

plants, the flyers, the swimmers, the crawlers, and each other. We

are all part of the Story of the Land …”

|

|

Figure

5

And

the Story is Not Finished

Note.

The text reads: “AND THE STORY IS NOT FINISHED …

We choose to heal the land and the broken relationships here so

that everyone can learn and grow in harmony with nature and each

other for as long as the sun shines, the grass grows and the river

flows.”

|

While

I watched my son recite the land acknowledgment on that hot summer

day at the end of his kindergarten year, I was filled with hope.

Seeing children as active participants in the story of the land and

providing those opportunities within ECEC programs, moves beyond

current narratives of ECEC as an investment in children as future

workers, as a jump start for the economy, or as an essential service

for women’s equality. This alternative narrative brings forth

the importance of relationships, for children, for adults, for land.

Could these actions and this text be a way to envision how we shall

live (Tuck, 2018a) within ECEC? Perhaps this is an example of the

possibilities that the incommensurability of Indigenous and colonial

worldviews can offer to ECEC pedagogies (Ashton, 2015) and how it can

look if we take this “incommensurability seriously as a

pedagogical starting point” (Ashton, 2015, p. 91).

My

son’s kindergarten teacher reimagined her place in the story of

the land; she troubled her teaching practice and decentered her

settler knowledge, creating space for the knowledge of Elders,

community and the land, building relationships that cross boundaries

(Henderson & Little Bear, 2021) and impact learning. She also

worked alongside children in authentic and productive ways. In our

first webinar, Greenwood (2020), referring to her dream of a world in

which all children are free from oppression, powerfully stated,

“Children are not just passive recipients but that this better

world will be achieved through them” (1:58–2:06).

Watching the children live out their land acknowledgement embodies

what Greenwood has expressed. Children, when provided with the

opportunity, are active participants in their story of the land.

Following Tuck’s (2009) provocation to move from a

damage-centred focus in research to one of desire while bringing what

we have learned about damage along with us, I see hope in this

moment.

This

brings me back to a recent conversation our group had when Monica

asked: “What is the thread of hope that runs through this

work?” We paused in silence, thinking about the pockets of hope

exposed within the seemingly crumbling systems cascading around us.

Then we spoke … We see hope in the amazing work some educators

are doing. We see hope in the underground, behind the scenes work of

policy influencers and makers, passionate about universally available

childcare in Canada. In spite of the persistence of post-colonial

practices, we see hope in the cracks in colonialism. We see hope in

young children.

In

Closing … Shifting From Damage to Desire

In

this article our intent has been to narrate change in ECEC in Canada

specifically as we experienced it in the context of pandemic as

provocation, and within the ECE Narratives project. In

questioning the potency of dominant narratives, our minor stories

(Taylor, 2020) took on new meaning as a productive starting point for

moving our thinking from damage to desire. As we engaged in

conversation about alternative narratives and new texts, we were able

to co-create a bricolage of minor stories. We became more fully aware

of the deeply embedded and damaging nature of colonialism and how

paralyzing it can be, and of the possibilities of moving beyond—from

damage to desire. In Monica’s narrative of change there was a

movement from “us” and “them” to “we,”

a recognition that there are no short-cuts in system building, that

the search for one right narrative is naïve, and that we cannot

let complexity inertia become an excuse for inaction. In Pam’s

narrating of change, she considers our responsibilities as Treaty

People and the spaces created by particular Indigenous texts centring

Indigenous knowledges, languages, and cultures. These texts shift

from damage to desire while presenting the possibility of creating

new Indigenous futures, and new ways of being for White settlers that

focus on the taking up of incommensurability as a pedagogical

starting point (Ashton, 2015) for ourselves and the larger life

endeavours in which we are engaged. Jane narrates the ways in which

working with curriculum frameworks opens a space for educators to

value their own work, and brings forward thinking that positions

incommensurability as a productive space in relationship to ECEC

curricular goals of diversity, inclusion, and difference. In Esther’s

narrating of change, she sees hope in the way that one educator was

able to co-create opportunities through which children’s ways

of knowing were valued, local knowledge was honoured, and the agency

of the land was acknowledged. Through intentional and caring practice

children and adults were able to work towards finding their place in

the story of the land.

Because

of the pandemic we had extended opportunities to experience movement

of thought through conversation in an extraordinary moment of change

for ECEC in Canada. Conversation, community, co-creation, and

co-authorship were made possible through the use of various digital

platforms. The crisis in ECEC, made more visible by the pandemic,

reframed the scope of our research. Our “throwntogetherness”

in a pandemic moment inspired us to bring people together for a

broader public conversation in a virtual space, to story a

multi-faceted bricolage, narrating change in ECEC in Canada.

References

Ashton,

E. (2015). Troubling settlerness in early childhood curriculum

development. In V. Pacini-Ketchabaw & A. Taylor (Eds.).

Unsettling the colonial places and spaces of early childhood

education (pp. 81–97). Routledge.

Beach,

J., & Ferns, C. (2015). From child care markets to child care

system. Our

Schools/Our Selves, 24(4),

53–61.

https://policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/National%20Office/2015/09/OS120_Summer2015_Child_Care_Market_to_Child_Care_System.pdf

Bennett,

J. (2005). Curriculum issues in national policy-making. European

Early Childhood Education Research Journal,

13(2),

5–23.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13502930585209641

Berry,

K. (2004). Structures of bricolage and complexity. In J. Kincheloe &

K. Berry (Eds.), Rigour and complexity in educational research:

Conceptualizing the bricolage (pp.103–127). Open University

Press.

Bezanson,

K. (2018). Feminism, federalism and families: Canada's mixed social

policy architecture. Journal

of Law and Equality,

14(1),

169–197.

https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/utjle/article/view/30894

Bezanson,

K., & Bevan, A., & Lysack, M. (March 8, 2021). How

do you build a Canada-wide childcare system? Fund the services.

First Policy Response Commentary.

https://policyresponse.ca/how-do-you-build-a-canada-wide-childcare-system-fund-the-services/

Bird,

F., Henripin, J., Humphrey, J. P., Lange, L. M., Lapointe, J.,

Gregory MacGill, E., & Ogilvie, D. (1970). Report of the Royal

Commission on the status of women in Canada. Information Canada.

https://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/9.699583/publication.html

Braidotti,

R. (2020). We are in this together, but we are not one and the same.

Bioethical

Inquiry 17,

465–469. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-020-10017-8

Campbell,

N, (2005). Shi-shi-etko. Illustrations by Kim LaFave.

Groundwood Press.

Couture-Grondin,

E. (2018). Literary relationships: Settler feminist readings of

visions of justice in Indigenous women’s first-person

narratives (Order No. 10838032). [Doctoral Dissertation,

University of Toronto]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

Early

Childhood Research and Development Team. (2007). New

Brunswick curriculum framework for early learning and child

care~English. Department

of Social Development. University of New Brunswick.

https://www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/departments/education/elcc/content/curriculum/curriculum_framework.html

Friendly,

M., & Prentice, S. (2009). About Canada: Childcare.

Fernwood.

Geertz,

C. (1972). Deep play: Notes on the Balinese cockfight. Daedelus,

101, 1–37.

Gould,

K. (2022, June). Symposium address. What now for childcare?

What Now for Child Care, Ottawa, ON.

https://childcarecanada.org/resources/issue-files/what-now-child-care

Government

of Canada. (2018). Indigenous

early learning and child care framework. Employment

and Social Development Canada.

https://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/9.856667/publication.html

Greenwood,

M. (2020, June 10). Moving

forward with uncertainty: The pandemic as déclencheur* for a

competent ECEC system across Canada/ Aller de l’avant dans

l’incertitude : la pandémie comme catalyseur* de

transformation d’un système plus adapté

d’éducation à la petite enfance à travers

le Canada, question 1.3

[Webinar

1]. ECE

Narratives. https://ecenarratives.opened.ca/webinar-1-question-3/

Haraway,

D. (2016). Staying with the trouble. Duke University

Press.

Henderson,

S., & Little Bear, L. (2021). Coming home: A journey through the

trans-systematic knowledge systems. Engaged

Scholar Journal: Community-Engaged Research, Teaching and Learning,

7(1),

205–216. https://esj.usask.ca/index.php/esj/article/view/70771

Hewes,

J., Lirette, P., Makovichuk, L., & McCarron, R. (2019). Animating

a curriculum framework through educator co-inquiry: Co-Learning,

co-researching, and co-imagining possibilities. Journal

of Childhood Studies, 44(1),

37–53. https://doi.org/10.18357/jcs.v44i1.18776

Hewes,

J., & Lirette, P. (2018, October). Gathering as a community of

learners [Conference Session]. 26th Reconceptualising

Early Childhood Education (RECE) Conference. Copenhagen, DK.

Hewes,

J., Whitty, P., Aamot, B., Schaly, E., Sibbald, J., & Ursuliak,

K. (2016). Unfreezing Disney’s Frozen

through

playful and intentional co-authoring/co-playing. Canadian

Journal of Education, 39(3),

1–25.

http://journals.sfu.ca/cje/index.php/cje-rce/article/view/2089/1879

Iannacci,

L., & Whitty, P. (2009). Early childhood curricula:

Reconceptualist perspectives. Detselig Enterprises Limited.

Johnson,

H. (2007). Two families: Treaties and government. Purich

Publishing.

Johnson,

M. (2021). Decolonial performance practice: Witnessing with an ethic

of incommensurability. Performance

of the Real,

2.

https://doi.org/10.21428/b54437e2.0da249c1

Langford,

R., Prentice, S., Richardson, B., & Albanese, P. (2016).

Conflictual and cooperative childcare politics in Canada.

International

Journal of Child Care and Education Policy,

10(1),

1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40723-016-0017-3

Little

Bear, L. (2000). Jagged worldviews colliding. In M. Battiste (Ed.),

Reclaiming Indigenous voice and vision (pp. 77–85).

UBC Press.

Mahon,

R. (2000). The never-ending story: The struggle for universal child

care policy in the 1970s. The

Canadian Historical Review,

81(4),

582–615. https://doi.org/10.3138/chr-102-s3-013

Makovichuk,

L., Lirette, P., Hewes, J., & Aamot, B. (2017). Playing, learning

and meaning making: Early childhood curriculum unfolding. Early

Childhood Education, 44(2),

3–10.

https://roam.macewan.ca/bitstreams/5ed4b94d-b7ba-4692-b0c6-ca3cfde75669/download

Massey,

D. (2005). For space (3rd ed.). SAGE.

Monsef,

M. (2020,

June 10). Moving

forward with uncertainty: The pandemic as déclencheur* for a

competent ECEC system across Canada/ Aller de l’avant dans

l’incertitude : la pandémie comme catalyseur* de

transformation d’un système plus adapté

d’éducation à la petite enfance à travers

le Canada [Webinar

1]. ECE

Narratives. https://ecenarratives.opened.ca/policy-narratives/

Moss,

P. (2018). Alternative narratives in early childhood education:

Introduction to students and practitioners. Routledge.

Organization

of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). (2001). Starting

strong: Early childhood education and care.

https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264192829-en

Organization

of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). (2006). Starting

Strong II: Early childhood education and care.

https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264035461-en

Pacini-Ketchabaw,

V. (Ed.). (2010). Flows, rhythms, & intensities of early

childhood education. Peter Lang Publishing.

Pacini-Ketchabaw,

V. & Pence, A. (2005). Contextualizing the reconceptualist

movement in Canadian early childhood education. Research

Connections Canada. Canadian

Child Care Federation.

http://web.uvic.ca/fnpp/documents/01.Pacini_Pence_Contextualizing.pdf

Pasolli,

L. (2019).

An Analysis of the Multilateral Early Learning and Child Care

Framework and the Early Learning and Child Care Bilateral Agreements.

Child Care Now (Child Care Advocacy Association of Canada) with the

Muttart Foundation.

https://muttart.org/an-analysis-of-the-multilateral-early-learning-and-child-care-framework-and-the-early-learning-and-child-care-bilateral-agreements/

Penn,

H. (2011). Quality in early childhood services: An international

perspective. Open University Press.

Penn,

H. (2019). ‘Be realistic, demand the impossible’:

A memoir of work in childcare and education. Routledge.

Robertson,

D. (2016). When we were alone (J. Flett, Illus.). Portage &

Main Press.

Rudolph,

N. (2017). Hierarchies of knowledge, incommensurabilities and

silences in South African ECD policy: Whose knowledge counts? Journal

of Pedagogy, 8(1),

77–98. https://doi.org/10.1515/jped-2017-0004

Supernant,

K. (2022, May 26). Every child matters: One year after the unmarked

graves of 215 Indigenous children were found in Kamloops.

The Conversation.

https://theconversation.com/every-child-matters-one-year-after-the-unmarked-graves-of-215-indigenous-children-were-found-in-kamloops-183778

Tasker,

J. P. (2021, April 19). Liberals promise $30B over 5 years to create

national child-care system. CBC.

https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/federal-budget-freeland-tasker-1.5991137

Taylor,

A. (2020). Countering the conceits of the Anthropos: Scaling down and

researching with minor players. Discourse:

Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education,

41(3),

340–358, https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2019.1583822

Tesar,

M. (2015). Te Whariki in Aotearoa New Zealand: Witnessing and

resisting neo-liberal and neo-colonial discourses in early childhood

education. In V. Pacini-Ketchabaw & A. Taylor (Eds.).

Unsettling the colonial places and spaces of early childhood

education (pp. 174–201). Routledge.

Tuck,

E. (2009). Suspending damage: A letter to communities. Harvard

Educational Review, 79(3), 409-427.

Tuck,

E. (2018a). Biting the university that feeds us. In M. Spooner &

J. McNinch (Eds.), Dissident

knowledge in higher education

(pp.

149-167). University of Regina.

http://www.roadtriptravelogues.com/uploads/1/1/6/9/116921398/dissident_knowledge_in_higher_education.pdf

Tuck,

E. (2018b, March 15-16). I do not want to haunt you but I will:

Indigenous feminist theorizing on reluctant theories of change

[Presentation]. Indigenous Feminist Workshop. University of

Alberta. https://vimeo.com/259409100

Tuck,

E. & Yang, W.K. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor.

Decolonization:

Indigeneity, Education & Society 1(1),

1-40.

Whitty,

P., Lysack, M., Lirette, P., Lehrer, J., & Hewes, J. (2020).

Passionate about early childhood educational policy, practice, and

pedagogy: Exploring intersections between discourses, experiences,

and feelings … knitting new terms of belonging. Global

Education Review, 7(2),

8–23. https://ger.mercy.edu/index.php/ger/article/view/541

Whitty,

P., Hewes, J., Rose, S., Lirette, P., & Makovichuk, L. (2018).

(Re)encountering walls, tattoos, and chickadees: Disrupting

discursive tenacity. Journal

of Childhood Studies, 43(2),

1–16. https://journals.uvic.ca/index.php/jcs/article/view/18574

Whitty,

P. (2009). Towards designing a post-foundational curriculum document.

In L. Iannaci & P. Whitty (Eds.), Early childhood curricula:

Reconceptualist perspectives (pp. 35–62). Brush

Publications.

Yalnizyan,

A. (2020, September 14). Recovery depends on childcare strategy to

get women back to work. First

Policy Response.

https://policyresponse.ca/recoery-depends-on-childcare-strategy-to-get-women-back-to-work/

Endnotes

[1]

We

use the term ECEC throughout the paper to be consistent with the

terminology of the OECD. In Canada ECEC is also commonly referred to

as early learning and child care (ELCC)

in

the context of the frameworks.

[2]

The Alberta framework was first published in 2014 as Play

Participation, and Possibilities: An Early Learning and Child Care

Curriculum Framework for Alberta.

In 2018, it was re-issued as Flight:

Alberta’s Early Learning and Care Framework.