Node-ified

Ethics: Contesting Codified Ethics as Unethical in ECEC in Ontario

Lisa

Johnston

York

University

Author’s

Note

Lisa

K. Johnston https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2209-2845

Correspondence

concerning this article should be addressed to Lisa K. Johnston, York

University, Winters College, 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, ON M3J 1P3.

Email: lkj@yorku.ca

____________________

Are

codes of ethics ethical? Some argue that the reduction of ethics into

universalized moral rules favours a scientific and technical

rationality for solving problems over an ethical and political

response to issues encountered in daily human and more-than human

relations (Dahlberg & Moss, 2005; Todd, 2003). I begin this

article by situating code of ethics in the broader

professionalization movement in early childhood education and care

(ECEC). Though codes of ethics are common in ECEC, emerging out of

the broader professionalization movement in Europe, Australia, New

Zealand, the United States, and Canada (Association of Early

Childhood Educators Ontario, 2008; Australian Early Childhood

Association, 1990; College of ECE, 2017; Early Education, 2011;

Feeney & Kipnis, 1989; The Office of Early Childhood Education,

2022), regulatory bodies, such as the College of ECE in Ontario, are

rare. The rarity of regulatory bodies in ECEC means that they have

not been explicitly included in critiques of the instruments of

professionalization, nor in advocacy regarding regulation of the

sector. In this article, I contest the ethical as described in codes

of ethics both generally and specifically as they have become legally

enforceable in the ECEC sector in Ontario through the establishment

of the College of ECE (2017). Thinking with Eve Tuck’s (2018)

question of “How shall we live?” (p. 157) and a critical

invitation from Sharon Todd (2003), I consider how ethics in

education might be “rethought together as a relation across

difference” (p. 2). Drawing upon Gunilla Dahlberg and Peter

Moss (2005), I discuss the dematerialization of early childhood

educators (ECEs) and the instrumentalization of ECEC in Ontario

through the implementation of the Code of Ethics by the College of

Early Childhood Education. I engage in a speculative critique of

codified ethics located within a regulatory body by invoking the

imagery of nodes in Alex Rivera’s (2008) film Sleep

Dealer.[1]

The film depicts a violent techno-rational step into a dystopian

future where workers are connected to a network through cables and

wires inserted into their bodies via nodes. I work conceptually with

the idea of nodes, depicted in the film as points of connection in a

network, to present a haunting metaphor for the dematerializing and

instrumentalizing effects of codified ethics on ECEs, and in

conversation with Joanna Zylinska (2014) and Tim Ingold (2011), I

reframe instrumentalized nodes/codes of ethics within the complexity

of knots and meshworks to recover the ethical in early childhood

education. I offer this speculative piece as both a warning against

the instrumentalization of ECEs and a call to activism to reposition

ethics as a relational practice in ECEC and to reclaim the imagery of

nodes/knots as points of ethical relations (Ingold, 2011; Zylinska,

2014).

Codes

of Ethics and the ECE Professionalization Movement

During

the late 1980s and early 1990s movements to professionalize ECEC were

gaining momentum across Europe, the United States, Australia, New

Zealand, and Canada (Cannella, 1997; Langford et al., 2013; Osgoode,

2006; Popkewitz, 1994; Saracho & Spodek, 1993; Urban et al.,

2012). Professionalization in ECEC was driven by a number of factors

including, but not limited to, an increasing demand for the

accountability of ECEs by the public and the struggle by ECEs

themselves for better wages and working conditions as well as the

recognition of ECEC as professional work (Cannella, 1997; Langford et

al., 2013; Osgoode, 2006; Popkewitz, 1994; Saracho & Spodek,

1993; Urban et al., 2012). In the mid-20th century, in Canada and the

U.S. specifically, the proliferation of child study and child

development theories began to form the foundations of preservice

training programs for ECEs (Cannella, 1997), which further

contributed other strategies of professionalization such as

certification, credentialing and licensing of ECEs and ECEC programs

(AECEO, 2010; Saracho & Spodek, 1993). The creation of codes of

ethics also emerged out of this movement toward professionalization

and were intended to provide guidance and consistency for ECEs in

navigating the moral and ethical dilemmas they grappled with in their

everyday work with young children and families (AECA, 1990; Early

Education, 2011; NAEYC, 1998; see also Feeney & Kipnis 1989;

Katz, 1984; The Office of Early Childhood Education, 2022).

ECEs

in Ontario, like their counterparts internationally, have

historically suffered from low wages and poor working conditions

including a lack of respect, job security, and benefits (Child Care

Sector Human Resources Council, 2013; Doherty et al., 2000).

Achieving professional status, it was hoped, would address these

issues and bring about better wages and working conditions for ECEs

(Langford et al., 2013; Urban et al., 2012). As the professional

association for ECEs since 1950, the Association of Early Childhood

Educators Ontario (AECEO) has been actively working toward the

professionalization of ECEs through certification, credentialing, and

professional development as well as actively advocating for the

recognition ECEs in the form of professional pay and decent work

conditions (AECEO, 2016; Langford et al., 2013). The AECEO developed

its own code of ethics in 1982, which was revised in 1994 and

distributed to all licensed childcare programs in Ontario (AECEO,

2010). Two years later, the AECEO campaigned and proposed legislation

for the establishment of a regulatory body. Claims put forward by the

AECEO suggested that a regulatory body would realize the goal of

“legislative recognition” of ECEC as a profession and,

therefore, was expected to naturally translate into professional pay

and better working conditions (AECEO, 2010, p. 21). Though the

AECEO’s attempt to pass their bill for a regulatory body was

unsuccessful in the Ontario Legislature, they continued to lobby for

a College of ECE and in the meantime voluntarily assumed the role of

a regulatory body for ECEs predominantly though their certification

process (AECEO, 2010).

In

2007, the College of ECE was finally established in Ontario. The

first of its kind, this regulatory body ushered in a new era of

professionalization signaling progress and promise for ECEs in

Ontario. With the creation of the College of ECE a new code of ethics

was introduced. Like its predecessor, the College of ECE’s code

of ethics outlined ECEs’ moral and ethical responsibilities to

children, families, colleagues, the profession, the community, and

the public (College of ECE, 2017, p. 7). Alongside the code of

ethics, the College of ECE also introduced six standards of practice:

Standard I: Caring and Responsive Relationships, Standard II

Curriculum and Pedagogy, Standard III: Safety Health and Well-being,

Standard IV: Professionalism and Leadership, Standard V: Professional

Boundaries, Dual Relationships, and Conflicts of Interest, and

Standard VI: Confidentiality, Release of Information and Duty to

Report. Each standard has three sections that outline the principles,

knowledge, and practices required of ECEs in their practice as

professionals (College of ECE, 2017, pp. 8-20).

The

role of the College of ECE in establishing professional status for

ECEs, however, is often misunderstood. It does not provide any direct

benefits to ECEs themselves but rather indirectly raises the

professional status of ECEs through its mandate to protect the public

and to maintain the integrity of the profession (College of ECE,

2017). In exchange for the right to practice as and use the protected

title of Registered Early Childhood Educator (RECE), RECEs must not

only abide by the College of ECE’s Code of Ethics and Standards

of Practice, but they must also meet the minimum requirements of a

2-year college diploma in Early Childhood Education at an accredited

college or university, pay annual professional dues comparable to

Ontario Certified Teachers (Ontario College of Teachers, 2022), and

demonstrate evidence of their continuous professional learning (CPL).

While

most codes of ethics in ECEC act as prescriptions for what

professionals should and should not do, the location of a code of

ethics in a regulatory body necessitates legal sanctions as

consequences for non-compliance. Lichtenberg (1996) argued that codes

of ethics do not necessarily require sanctions; however, when they

do, they, in fact, contradict the true meaning of ethics because they

impose external motives for acting ethically. This is evident in the

way the Code of Ethics and Standards of Practice as well as the other

professional requirements mentioned are enforced by the College of

ECE. RECEs are held accountable through a public registry, random

audits of their continuous professional learning portfolios, and

disciplinary processes and potential consequences, such as losing

their license to practice, related to reported violations of the Code

of Ethics and Standards of Practice.

Initially

seen as a victory in the fight for professional recognition of ECEs,

the establishment of the College of ECE has arguably failed to

deliver that promise. Instead of an improvement in ECEs’ wages

and working conditions, RECEs now face increased expectations and

accountability, tighter surveillance, and more serious consequences

for not meeting expectations. The AECEO itself acknowledges and

identifies the discrepancy between the increase in professional

expectations of RECEs and the corresponding lack of improvement in

wages and working conditions as the “professionalization gap”

(AECEO, 2016, p. 2). The irony is that the push for

professionalization has come from educators and advocates. In their

desire for change, educators have welcomed and even advocated for

more training, certification, licensing, credentialing, and even

regulations, such as codes of ethics, in the hopes that raising the

status of the profession would also result in raise in their pay,

improved working conditions and more respect to the profession

(Langford et al., 2013).

This

should come as no surprise, however. Though the struggle for

professionalization, and the idea of what professionalism means in

ECEC, has been important and critical for the feminist movement, it

also has its critics. In 1997, Gaile Cannella prophetically wrote,

“One can understand why women would hope that

professionalization would lead to advanced status, respect, and more

pay. However, professionalism has actually fostered the patriarchal,

modernist notion of control and rationality” (p. 147). Jayne

Osgood (2006) referred to this as the “regulatory gaze”

(p. 5), pointing out that professionalism is a masculinist construct

that cannot account for the emotionality of the work that educators

do in caring for young children and where emotionality has no

exchange value. Thus, when professionalism’s patriarchal logics

are applied to a feminized profession the result is increased

regulation in the form of top-down policy making and disciplinary

technologies, thereby creating, as I will discuss in the next

section, ECEs as technicians.

Contesting

Codified Ethics

My

primary concern in writing this article is that while Ontario has had

a code of ethics since 1982, it was not until it became legally

enforceable by the College of ECE that the code of ethics has come to

dominate the profession in Ontario, so much so that I wonder if we in

Ontario have lost sight of the ethical in ECEC. I explore the

discrepancy between codified ethics and the ethical by turning to

Todd (2003) who asks the question “WHAT, OR WHERE, is ethics in

relation to education?” (p. 1). For Todd (2003), codified

ethics instrumentalize education, making it about having the right

knowledge and applying moral codes passed down by “experts,”

implying that we as ordinary people do not already act ethically

towards others or that we are at least committed to acting ethically

towards others. Todd (2003) also asks, “And what does this say

about our experts’ attitudes toward the ‘ordinary people’

who, ostensibly, are waiting for knowledge to be bestowed upon them

that they might ‘become’ moral?” (p. 6). For ECEs,

I also ask, how does the code of ethics instrumentalize ECEC, and how

does it dematerialize the educator by implying that they become moral

when they adhere to the code handed to them, a code that is enforced

by the experts? Importantly, Todd (2003) also reminds us of the

position of experts and education in the context of colonialism and

imperialism, thereby questioning their authority in determining

universal moral codes. In this article, I am interested in exploring

Todd’s (2003) invitation to think about how “in focusing

on conditions instead of principles, codes, and rules, ethics might

be considered in terms of those moments of relationality that

resist codification” (p. 9).

Keeping

Todd’s questions in mind, I build on Dahlberg and Moss’s

(2005) extensive discussion of the instrumentalization of ECEC

through the discursive-material logics of neoliberalism and

psychological theories of child development and argue that the

codification of ethics in ECE completes the transformation

(dematerialization) of the educator into a worker-technician.

According to the Oxford English dictionary, the verb dematerialize

means “to deprive of material character or qualities; to render

immaterial” (Oxford University Press, n.d.). In this article, I

take up the concept of dematerialization to explore how ECEs become

estranged from their relational, ethical, and emotional selves,

disappearing as they are transformed into technicians through the

masculinist and instrumentalizing technologies of professionalism.

I

explore this transformation in conversation with the near dystopian

film Sleep Dealer written and directed by Alex Rivera (2008)

and specifically through the aesthetic device of the film’s

imagery of nodes and node workers from which I have derived the

concept of “node-ified” ethics. I draw on the following

quote by Dahlberg and Moss (2005), who described the ways that ECEs

are shaped by the logics of neoliberalism and return to it again and

again as I pick up its threads and weave them into my argument:

Increasingly

hegemonic economic and political regimes require the formation of a

particular subject, autonomous, active, flexible, response-able, a

bearer of rights and responsibilities, self-governing, a practitioner

of freedom. New and continuous forms of discipline and control

provide ever more effective ways to form and govern this subject. The

subject is inscribed with scientific knowledge and instrumental

rationality, forms of knowledge and reason connected to a regulatory

mode [code/node] of modernity pledged to dispense with uncertainty

and ambivalence. Technical solutions are an intrinsic part of

modernity’s instrumental culture. (p. 59)

Guided

by this quote, and images from the film, I trace the regulatory mode

of codified ethics through the aesthetic device of nodes that both

inscribe and form the subject of the worker/educator through the

instrumentalization of the work and the dematerialization of the

body. Following this, I will return to Todd (2003), in conversation

with Zylinska (2014) and Ingold (2011) to recover the conditions of

ethical relationality in ECEC. I position this conceptual and

speculative piece as both a warning and a call to activism, while

also recognizing that it is itself a moment of activism as I risk

engaging in a dark critique of the College of ECE in Ontario and

suggest that codified ethics may be leading toward a dystopian future

(if indeed we are not already there).

Sleep

Dealer by Alex Rivera

I

will now conjure the imagery of nodes as depicted in the film Sleep

Dealer as I weave in a critique of codified ethics through Todd

(2003) and Dahlberg and Moss (2005). Sleep Dealer (2008) is

set in Tijuana Mexico in a near dystopian future where South American

migrant workers no longer need to cross the border to work in the

United States. Instead, through nodes surgically implanted into their

bodies, workers can connect remotely to robots somewhere across the

border in the U.S. By manipulating these robots, they can pick fruit,

build skyscrapers, and even take care of children.

In

large warehouses, row upon row of node workers in oxygen masks and

translucent contact lenses that allow them to see through the “eyes”

of the robots, move in slow, pantomime-like motion manipulating their

robot on the other side (see Figures 1 and 2). Nodes in the film are

used as a compelling and violent techno-rational solution to the

“problem” of migrant workers. Nodes offer a future of

“all the work without the worker” (Rivera, 2008, 36:27).

Solving the problem of the unpredictable, unreliable, uncertain

worker is also the function of codified ethics where the worker/RECE

becomes invisible and irrelevant so long as they perform the work and

do not violate the code.

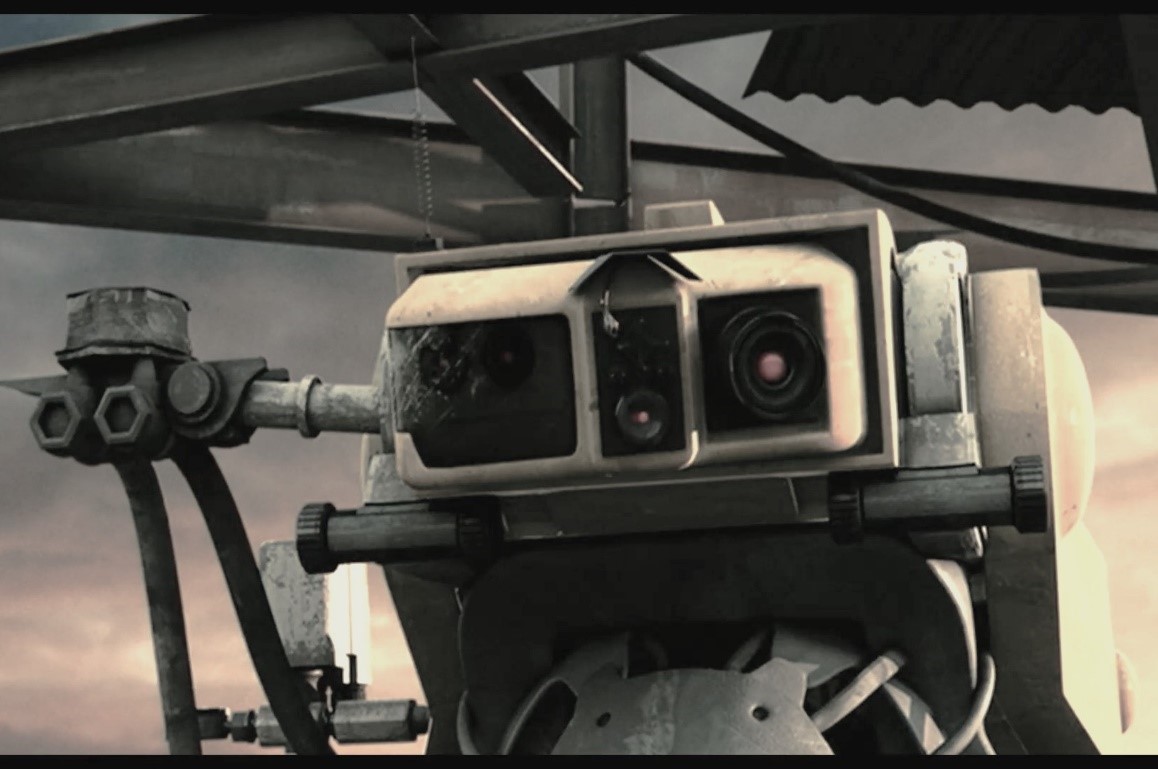

|

Figure

1

Image

of the Main Character Memo as a Node Worker

Note.

Image from the film Sleep Dealer (Rivera, 2008, 39:13).

Copyright 2008 by Alex Rivera. Used with permission.

|

|

Figure

2

Image

of Node Workers in a Factory

|

|

Note.

Image from the film Sleep Dealer (Rivera, 2008, 316:19).

Copyright 2008 by Alex Rivera. Used with permission.

|

In

the film, we meet the main character, Memo Cruz. He and his family

are farmers in a small South American town where the government

controls the water, held in a heavily guarded reservoir behind a huge

dam. Memo and his father must pay for small amounts of water to take

back home to water their meagre crops and to use for cooking and

washing. The government is always looking out for aqua terrorists who

try to steal the water. When Memo’s home-made transistor radio

is noticed by the government, he is mistakenly targeted as an

aqua-terrorist. A drone is sent to bomb his home, killing his father.

Devastated and distraught that his home-made radio caused the death

of his father, Memo leaves home and heads for Tijuana. He has heard

of nodes and hopes that he can become a node worker so that he can

send money back home to support his family. For Memo, the idea of

becoming a node worker is uncertain and yet it holds promise as the

solution to his desperate situation, much like the Ontario ECE

professionalization movement’s desire for a College of ECE and

codified ethics to solve the desperate problem of poor wages and

working conditions.

We

also meet Rudy Ramirez, the soldier who carries out the drone attack

that kills Memo’s father. In this dystopian reality, drone

attacks are televised like game shows and incite viewers in the fight

against aqua-terrorists. This is Rudy’s first mission. He

controls the drones through his own implanted nodes. The first drone

attack is a direct hit on Memo’s house and as his drone hovers

over the burning building, Rudy watches Memo’s father drag

himself out of the house bloodied and broken but still alive. Memo’s

father looks at the drone hovering over him. The host of the show

announces to the audience that it is a rare occurrence for a soldier

to get a chance to look into the face of the enemy. The show host and

the audience are in a frenzy as they cheer on Rudy to kill the

terrorist. As Rudy looks into the pleading face of Memo’s

father, he realizes at the last second that Memo’s father is

not a terrorist at all, but it is too late. There is too much at

risk. He pulls the trigger. Deeply troubled by what he has done, Rudy

seeks out Memo to make things right and, in the end (spoiler alert),

Rudy uses his own node connection to blow up the dam in Memo’s

hometown.

What

does it mean to think of both codes of ethics and nodes as “technical

solutions [that] are an intrinsic part of modernity’s

instrumental culture” (Dahlberg & Moss, 2005, p. 59)?

Staying close to this description/depiction of the ECE in neoliberal

times, there are a number of points of connections between the

College of ECE’s Code of Ethics (2017) and Rivera’s

(2008) nodes that I wish to explore, namely the dematerialization and

instrumentalization of the ECE through the privileging of the

scientific and technical over the ethical and political, through

distance and the acceptance of regulation in exchange for the false

promise of freedom, and through forms of discipline and violence that

force compliance in exchange for the ethical and political. Or how we

get “all the work without the worker” (Rivera, 2008,

36:27).

Dematerialization

and Instrumentalization of the ECE

The

Privileging of the Scientific and Technical Over the Ethical and

Political

The

dematerialization of node workers bodies occurs directly with the act

of having nodes implanted into their arms and upper back. The human

body, as it was, disappears and is transformed into something else by

the implantation of nodes, which are like electronic ports in the

flesh into which needles attached to cables can be inserted.

Instrumentalization happens when the cables are inserted into the

nodes and connect to the Internet and to a corresponding robot

somewhere in the U.S. The imagery of the dematerialization of

workers’ bodies in the film through the implanting of nodes

(see Figures 3 and 4) can be imagined as the dematerialization of the

RECE through the implanting or inscribing of scientific knowledge

(child development) and instrumental rationality (neoliberal

regulation) transforming the RECE into a worker-technician. Once

implanted with nodes, ECEs, like node workers, can hook into the

network, the machine, “[in]to a regulatory mode [node/code] of

modernity” (Dahlberg & Moss, 2005, p. 56), into a

profession dominated by the instrumentalizing developmental and

neoliberal discourses that dominate it; discourses that do not

require or recognize complex ethical relationality but rather seek to

eradicate the “uncertainty and ambivalence” of human and

more-than-human relations (Dahlberg and Moss, 2005, p. 59) through

the neutral or apolitical application of codified ethics. I also see

the dematerialization of the human through nodes and codes of ethics

as related to Dahlberg and Moss’s (2005) de-politicization and

de-ethicalization of ECEC through the privileging of the scientific

and technical over the ethical and political. Taking the ethical and

political to be that which makes the human human, means that

reducing the human to the scientific and technical is in effect a

dematerialization of the early childhood educator into a replaceable

worker-technician. What is more, the scientific and technical also

“privileges the universal over the local” (p. 56) thus

dematerialization through distance becomes even more evident.

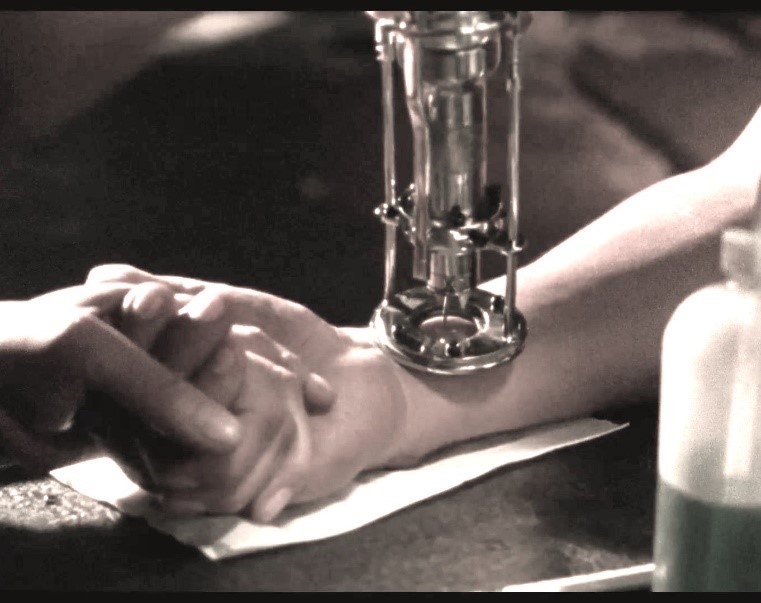

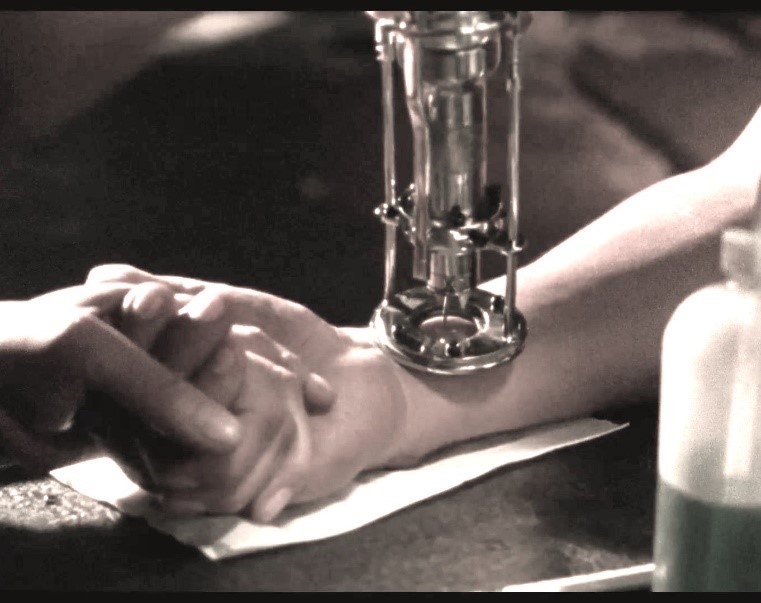

|

Figure

3

Nodes

Being Implanted Into Memo

Note.

Image from the film Sleep Dealer (Rivera, 2008, 35:02).

Copyright 2008 by Alex Rivera. Used with permission.

|

|

Figure

4

Connecting

to the Machine via Nodes

Note.

Image from the film Sleep Dealer (Rivera, 2008, 37:29).

Copyright 2008 by Alex Rivera. Used with permission.

|

The

organization of the College of ECE’s code of ethics around

distinct standards is also instrumentalizing and dematerializing as

it separates each standard into predetermined outcomes of achievement

that operate independent of each other. Each standard is like a

discreet node. Standard I: Caring and Responsive Relationships

(College of ECE, 2017, pp. 8–9), for example, stands alone from

all the other standards, yet it constitutes and infuses everything

that a RECE does. Separating caring and responsive relationships from

curriculum and pedagogy or health, safety and well-being

compartmentalizes and simplifies each of these expectations within

its own category, with its own set of recognizable and countable

outcomes. Caring and responsive relationships, however, are difficult

to quantify and are only recognizable when they are not caring or

responsive. Otherwise, caring and responsive relationships are taken

for granted while other standards that can be measured like

curriculum and pedagogy or health, safety, and well-being are given

precedence.

An

ethical dilemma that has been a central question in my own experience

as a RECE, and that drives my research, addresses the tensions

between the expectations for curriculum and pedagogy and engaging in

caring and responsive relationships with children in the everyday

moments of an early childhood classroom (Johnston, 2019). Without the

material support of paid planning time, I, like many RECEs, was

expected to complete all the requirements for planning, documenting,

and sharing documentation with families during the confines of the

workday, but often ended up working outside of my paid working hours

or completing paperwork while in program with children. When I made

an ethical choice one summer to forego the paperwork in favour of

truly being present with children and families, I was “caught”

and reprimanded during a licensing inspection for not having my

program plan complete. The messages I took away from this experience

were that the paperwork was more important than the relationships I

was engaged in, that I was not a “good” educator, and

that the curriculum I was implementing did not count if it was not

written down. The certainty of the paperwork outweighed the

uncertainty of relationships. I had tried to unhook myself from the

nodes and, therefore, became unrecognizable and unmanageable, so I

was re-inscribed with compliance with the techno-rationality of the

paperwork over the ethical relations.

Distance

and the Acceptance of Regulation in Exchange for the False Promise of

Freedom

The

nodes in Rivera’s (2008) film work to dematerialize the human

and the body in the way that the work takes place across vast

distances and transforms the human into a robot on the other side. I

see the “autonomous, active, flexible, response-able subject”

(Dahlberg & Moss, 2005, p. 59) as a dematerialized subject. In

Sleep Dealer distance manifests as no direct human oversight

of the node workers in the factory. Rather, workers are managed and

regulated from a distance through technology. In much the same way

the code of ethics regulates RECEs from a distance through their

formation as autonomous subjects, just as I was governed from a

distance through the paperwork. The images in Figure 5 depict a

moment in the film when Memo sees the reflection of the robot he is

controlling in a pane of glass. In this moment he realizes that he

has become the machine. Similarly, I argue that RECEs reflect and are

reflected by the College of ECE’s code of ethics and standards

of practice.

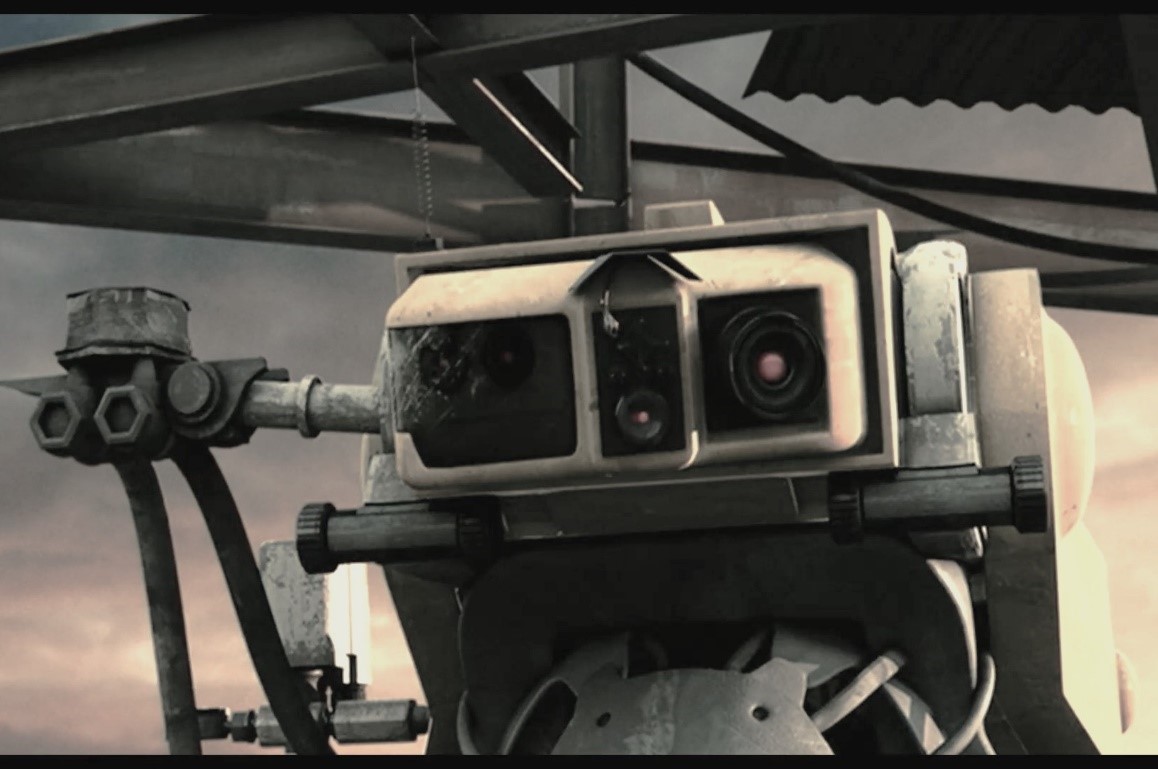

|

Figure

5

Memo

sees Himself as the Robot Reflected in a Pane of Glass

|

|

|

|

Note.

Images from the film Sleep Dealer (Rivera, 2008, 47:11 and

47:18). Copyright 2008 by Alex Rivera. Used with permission.

|

The

formation of the subject of the RECE thus occurs as the College of

ECE grants educators the right to call themselves a Registered ECE.

Simultaneously RECEs become subject to the code of ethics and

standards of practice in their dedication to upholding their ethical

(and personal) responsibilities to children, families, their

colleagues and the profession, the community and the public. Like

Todd’s (2003) argument that educators become receptacles for

knowledge in the form of codified ethics, as RECEs internalize the

code of ethics and standards of practice governing themselves

according to these codes and standards and acting autonomously within

them, they come to recognize themselves and are recognizable by their

knowledge of adherence to the code of ethics. Drawing on my own

example again, had I continued to sacrifice the relational and less

visible aspects of my work with children and families so that I could

complete the material aspects of the work, I would have been

recognized as a good educator (Johnston, 2019).

These

forms of regulation are readily taken up as the trade-off for the

freedom and promise of the technology. While nodes offer the promise

of work, the code of ethics offers the promise of

professionalization, creating the subject as a “bearer of

rights and responsibilities, self-governing, a practitioner of

freedom” (Dahlberg & Moss, 2005, p. 59). The freedom that

Dahlberg and Moss (2005) refer to here is a certain kind of freedom

that enables the autonomous subject to exercise “freedom-as-choice,

especially through competent participation in the marketplace and

rights-based contractual relationships” (p. 45). This illusion

of freedom, however, only works through an elaborate system of

convincing the population to govern themselves. For the ECEs this

elaborate system now includes a legally enforceable Code of Ethics

and Standards of Practice, continuous professional learning

requirements, yearly professional dues, and the threat of discipline

or someone reporting them to the College of ECE.

What

originally prompted me to investigate the imagery of nodes in Sleep

Dealer in relation to the code of ethics was this notion that,

just as workers in the film could only work if they had nodes, ECEs

in Ontario can only work and use the title of RECE, if they are

registered with the College of ECE. There is a widespread

misunderstanding that the College of ECE is supposed to do something

for ECEs, through the recognition of their education and expertise,

when in fact, as stated earlier, the mandate of the College is to

“protect the public interest and the integrity of the early

childhood education profession,” not the professional. Again,

it states that “no person shall engage in the practice of early

childhood education or hold himself or herself out as able to do so

unless the person holds a certificate of registration issued under

this Act” (College of ECE, 2017, p. 3). In other words, I

speculate that in a dystopian reality that this could easily be read

as one must have nodes to work as a RECE.

Forms

of Discipline and Violence That Force Compliance

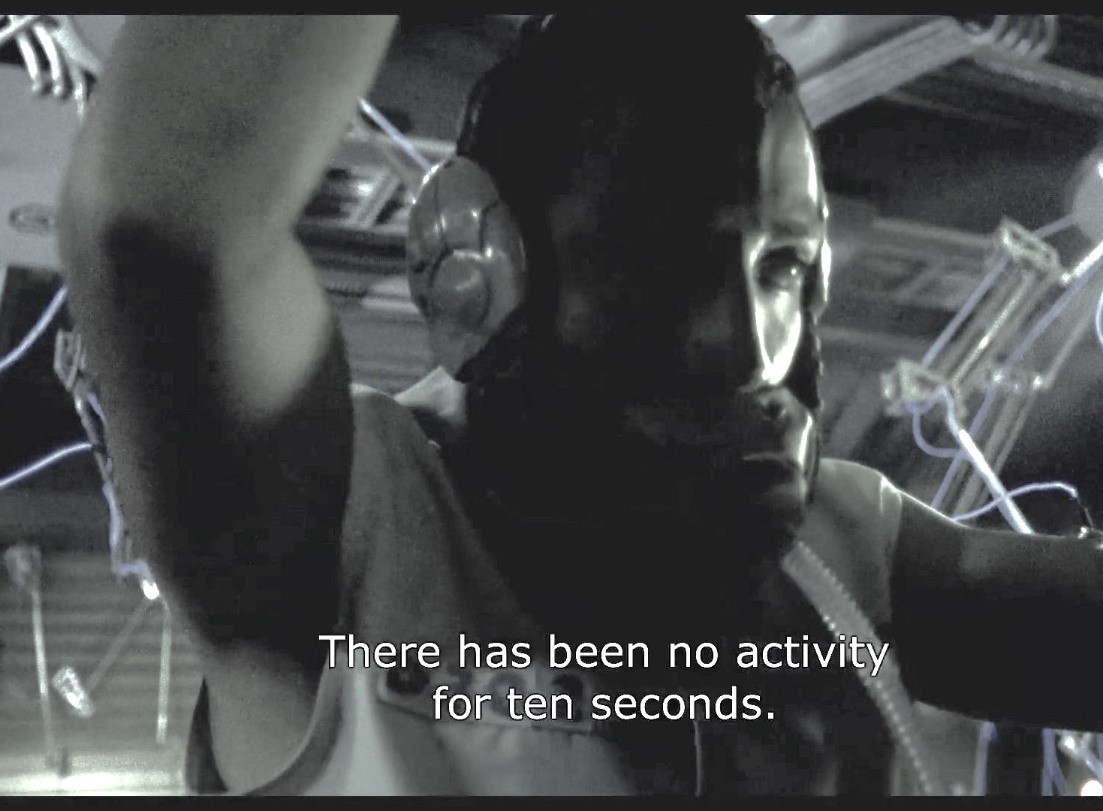

Finally,

once dematerialized, node workers/ECEs become surveillable,

punishable, and replaceable through the very connections that

legitimize their work. Node workers in the film are docked pay if the

network detects a pause in their productivity (see Figure 6). When

Memo nearly passes out from over work and exhaustion, he is startled

awake by an electronic voice telling him that he has been inactive

for 10 seconds and his salary will be adjusted. Node workers are also

susceptible to infection and possibly fatal surges of electricity

that may feedback from the network/machine into their bodies through

the nodes. Similarly, ECEs are highly susceptible to illness

especially during COVID when working with unvaccinated children. When

a node worker is no longer able to work, they are unhooked, and

another takes their place. Indeed, Dahlberg and Moss (2005) noted

that nation states must cultivate a “ready supply of suitable

labour – flexible, responsive, skillful” (p. 49) to

remain competitive global markets, recognizing preschools as

technologies that maintain current labour participation and foster

future human and social capital. Strikingly, Rivera’s (2008)

imagery of nodes and node workers in factories eerily echoes Dahlberg

and Moss’s (2005) use of the metaphor of the factory to

describe early childhood programs rendered by neoliberalism as

services rather than educational spaces. They noticed how “the

concept understands institutions as places for applying technologies

to children to produce predetermined, normative outcomes, for the

efficient processing of children by workers-as-technicians”

(Dahlberg & Moss, 2005, p. 28).

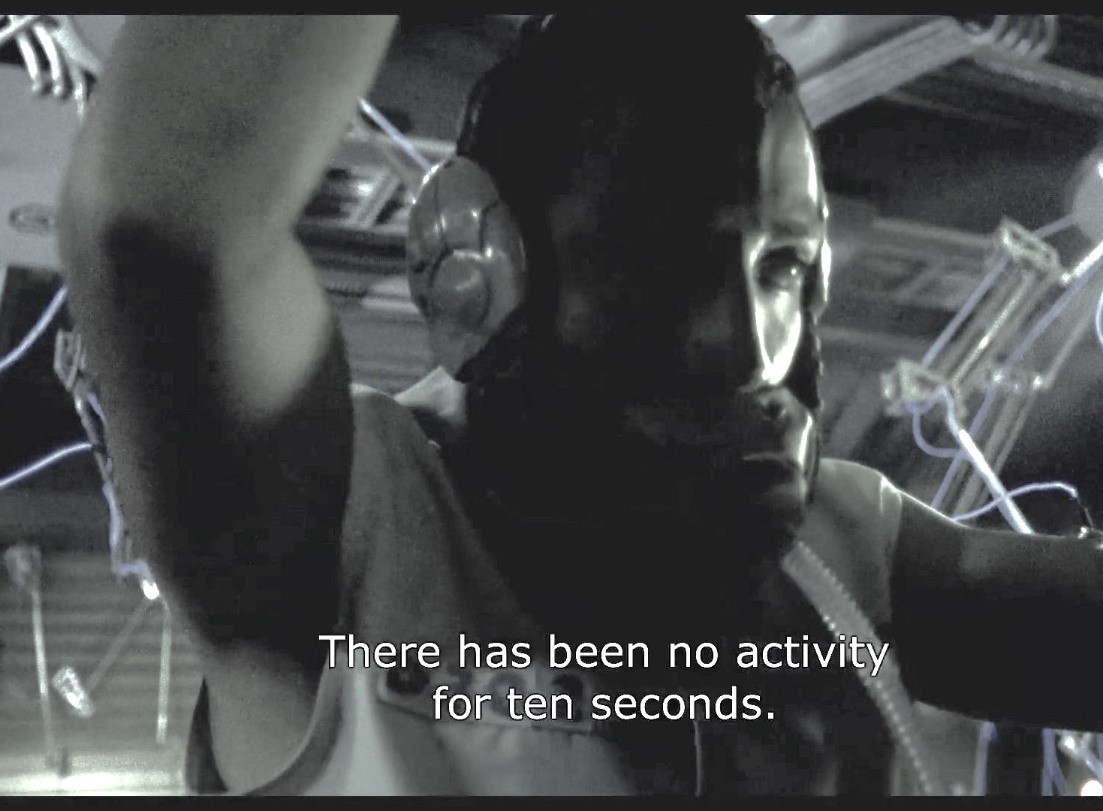

|

Figure

6

Memo’s

Productivity is Monitored by the Network/Machine.

|

|

|

|

Note.

Images from the film Sleep Dealer (Rivera, 2008, 1:06:28

and 1:06:37). Copyright 2008 by Alex Rivera. Used with permission.

|

RECEs,

subject to the code of ethics, are always under surveillance by the

College of ECE through their annual professional dues and through

random audits of their professional learning portfolios. RECEs are

also surveilled by the public through the public registry of members

in good standing, and by their supervisors and colleagues. Every RECE

under Standard IV: Professionalism and Leadership is responsible to

“report professional misconduct, incompetence and incapacity of

colleagues which could create a risk to the health or well-being of

children or others to the appropriate authorities” by their

colleagues (College of ECE, 2017, p. 15). This standard opens a lot

of grey areas and exposes the non-neutrality of codified ethics,

where racism, for example, can seep into personal and professional

judgements. Recall Todd’s (2003) warning that the moral

authority in determining codes of ethics is founded in colonial and

imperial ideals.

In

my own experience of being reprimanded for not having completed my

paperwork during a licensing inspection, I faced considerably mild

punishment; however, I was aware that it could have been worse had I

not been protected by being in a unionized position. Punishment such

as the suspension of one’s right to practice can also occur

because an RECE has not paid their professional dues on time, or they

have not completed their expectations for Continuous Professional

Learning (CPL), or they have falsely claimed to be a Registered ECE.

For RECEs who continue to make low wages paying yearly professional

dues can be a financial strain. As well the expectations for CPL

require time to engage in some form of learning that may or may not

be paid for, or that either requires time outside of working hours or

time off work to complete. The process of documenting one’s CPL

is also a time-consuming process that is not supported within the

paid workday. In essence, the expectations on RECEs for maintaining

their professional status directly impacts them financially. When

RECEs are working on their own time, they are essentially lowering

their wages even more, whereas registering as an RECE is meant to

significantly increase wages.

As

for replaceability, we are currently witnessing a retention crisis in

the ECE workforce in Ontario (Jones, 2022b) due to the COVID-19

pandemic and its exacerbation of the historic and systemic issues of

poor wages and working conditions. The response has been to increase

recruitment—simply train and replace a new set of workers.

Billions of dollars have been poured into compressed college programs

and free tuition for ECE students (for example see Durham College,

2022; George Brown College, 2022), while the current wage floor for

ECEs has been announced at $18.00 an hour, well below what ECEs who

work in Full Day Kindergarten make and well below what is needed to

have a livable wage in Ontario (Jones, 2022a). If RECEs are simply

replaceable then the transformation of the RECE into the worker

technician is complete. The ethical educator is not needed to be

present, only a dematerialized body that adheres to the “new

and continuous forms of discipline and control [that] provide ever

more effective ways to form and govern this subject” (Dahlberg

and Moss, 2005, p. 59). All the work without the worker. Is this how

we shall live?

Rethinking

the Ethical

I

return now to Todd (2003) and her concern with rethinking ethics and

education as an ethical relationality. What Todd (2003) means is that

we must not solely rely on an epistemological understanding of ethics

in education, an ethics based on having the right moral knowledge and

applying it to the knowability of the Other through categorizing

their social and material position in relation to intersecting forms

oppression. Rather, education

and educators must also take up a philosophical understanding of the

Other. Todd (2003) refers specifically to Levinas’s concept of

the Other as a radical alterity with whom we are already in ethical

relationality. How is ethical relationality already an orientation

that punctures the codified standard of caring and responsive

relationships? How might embodying this ethical relationality

re-materialize the ECE?

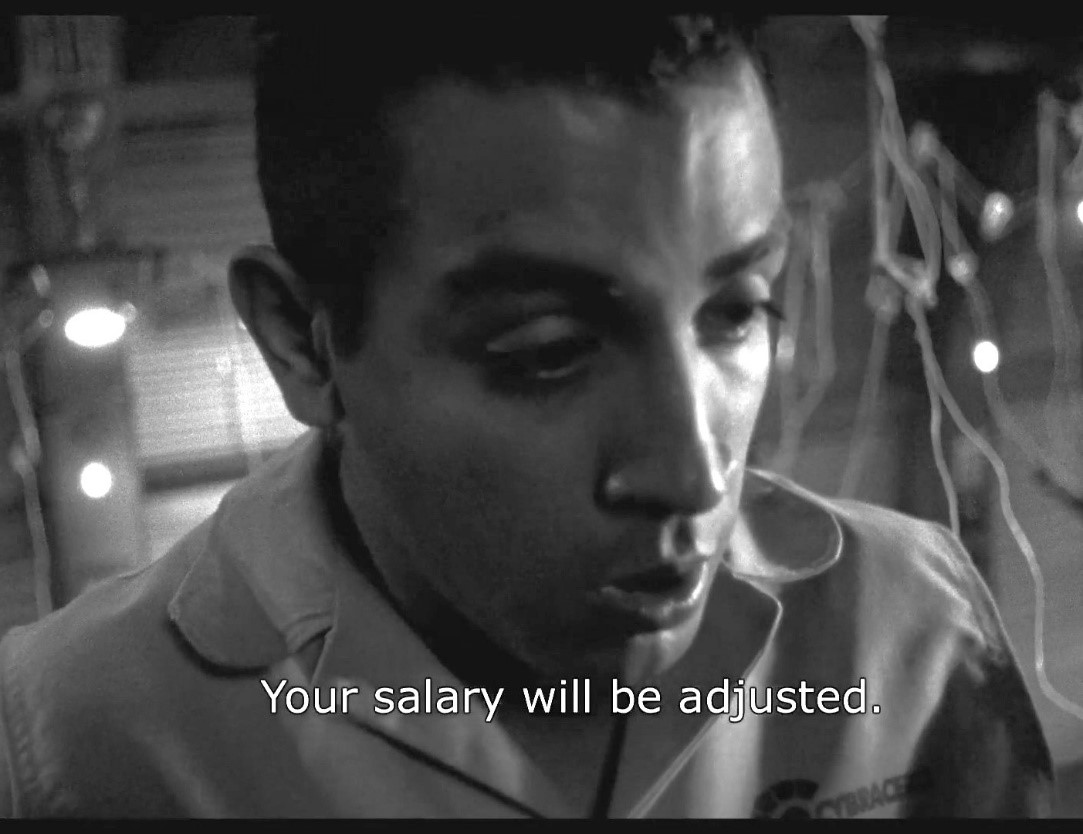

In

Sleep Dealer, Rudy Ramirez, the soldier and drone operator who

kills Memo’s father, thinking that he is killing an

aqua-terrorist, is confronted with the ontological otherness of

Memo’s father when he looks into his face (see Figure 7). This

moment creates uncertainty for Rudy that he cannot reconcile. While

the expectations of his employment are that he carries out orders in

destroying the enemy, once he is confronted with the face of the

Other as a radical alterity and not as an enemy (even though

in the moment of seeing the face of the Other, he does follow

orders), he is deeply troubled by his actions which he now

experiences as unethical.

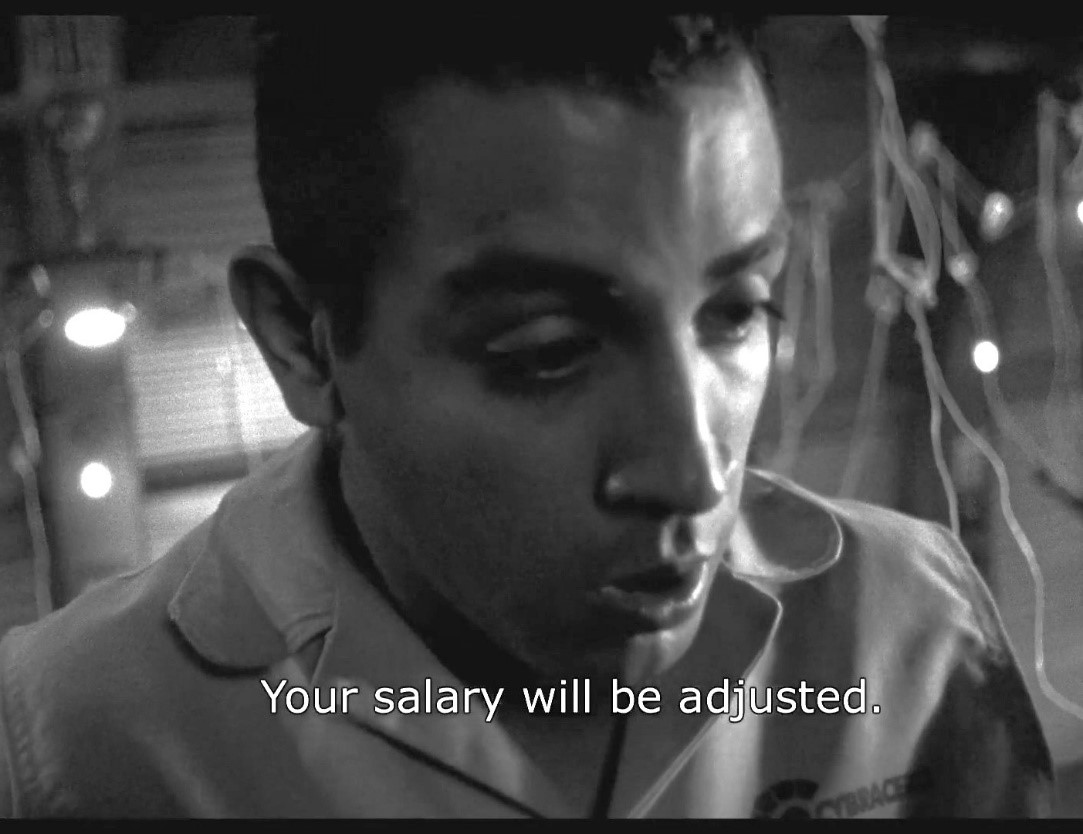

Figure

7

Rudy

Looks Into the Face of Memo’s Father.

Note.

Images from the film Sleep Dealer (Rivera, 2008, 16:16 and

16:31). Copyright 2008 by Alex Rivera. Reprinted with permission.

Rudy’s

next actions answer this question. No longer able to comply with the

expectations of the system, Rudy is compelled to make an ethical

choice to use his nodes, his connections to the system, to subvert

it. Together with Memo, he sneaks into the node factory, connects to

his drones, and uses them to blow up the dam in Memo’s village

(see Figure 8). This act brings relief and access to water for

everyone in Memo’s village. Though this act brings more

uncertainty for Rudy’s future, it also brings hope and a way of

living well together. So, “what happens to ethics and [early

childhood] education when learning is not about understanding the

other but about a relation to otherness prior to understanding?”

(Todd, 2003, p. 9). How might we recover nodes as a way of enacting

ethical relations like the way Rudy uses his nodes to act ethically

in relation to the Other? Again, Todd (2003) invited us to think

about how “conditions instead of principles, codes, and rules,

ethics might be considered in terms of those moments of

relationality that resist codification” (p. 9). What are

these conditions in ECEC?

Figure

8

Blowing

up the Dam.

Note.

Image from the film Sleep Dealer (Rivera, 2008, 1:22:11).

Copyright 2008 by Alex Rivera. Reprinted with permission.

In

Sleep Dealer, blowing up the dam is a moment of relationality

that resists codification. Rudy knows that killing Memo’s

father was unethical even though it was sanctioned by the state, and

he was lauded as a hero for killing an aqua-terrorist. Blowing up the

dam is an ethical act that defies the status quo and the disciplinary

technologies of the government. It is extremely risky and in fact

Rudy must leave Tijuana and go into hiding. He can no longer be a

soldier; he can no longer work. At the same time, it creates

conditions for an ethical relationality between Memo and Rudy that

extends beyond them to Memo’s family and his village. Likewise,

my choice to be present with children and families was also a moment

of relationality that resisted the codification of writing the

program plan. Time and support were the resources being held behind a

dam. In the neoliberal and patriarchal context of professionalism in

ECE, not having paid planning time meant that I was expected to do

more with less time and support and constantly worked against my

ethical commitment to cultivate caring and responsive relationships

with children and families. This is the reality for many RECEs

currently and even more so with the increased expectations for

cleaning and sanitizing due to the COVID-19 pandemic. It may be why

RECEs are leaving the profession and why preservice students are

choosing to bypass this profession and use their college training as

a stepping stone to somewhere else. For me, not doing the program

plan and writing this article are small moments of blowing up the

dam, of resisting the codified identity of professionalism. It is

risky. However, the current masculinist construction of

professionalism is also risky and harmful. There is too much at stake

not to take the risk. Ethical relations require time and are not

quantifiable. How then do we reconceptualize professionalism in ECE

as ethical relations? Materially RECEs need to have paid time in

their workday to collaborate with each other about what this means in

their own situated contexts. They also need other ways of thinking

about their work and valuing the ethical relations they engage in

every day.

In

considering how we might recover nodes as conditions for ethical

relations, I draw on Zylinska’s (2014) work to think about how

nodes are a network of relations in conversation with Ingold’s

(2011) concepts of meshworks and knots. Zylinska (2014) was concerned

about how we live in the context of the Anthropocene, this geologic

time that we are currently living in as one that has been greatly

impacted by human interaction, and that warnings of an oncoming

dystopian, ruined future. In response, Zylinska (2014) argued for a

minimal ethics that hinges on a repositioning of the human from a

place of supremacy, predicated on scientific ontologies that claim

certainty in knowledge, and that use knowledge to create

technological rationalities to justify their degradation of the

planet, to a place of human singularity that acknowledges our actions

as contingent and consequential. From this place of singularity,

Zylinska (2014) invited us as humans to see ourselves as situated

always and already in relation to the processes of matter and time

that extend beyond our capacity to comprehend them.

Zylinska

(2014) thought about the human as “an entangled and dynamically

constituted node in the network of relations to whom an address is

being made and upon whom an obligation is being placed, and who is

thus made-temporarily-singular precisely via this address” (p.

74). This conceptualization of a node is different from the

intentional function of nodes in Sleep Dealer in that it

invites uncertainty, ambivalence, and complexity in its singularity.

It resists codification. The instance when Rudy looks into the face

of Memo’s father a node is created that did not exist before.

It was not predetermined. Memo’s father addresses Rudy who is

obligated in that moment to respond to the radical alterity of the

Other. Even though he does not act ethically in this moment, the

obligation to make things right drives him to use his position as a

node in the network to respond to the address.

Further,

Zylinska (2014) reconceptualized nodes from a techno-rationality into

a relational ethics by reconceptualizing the network not as a

dematerializing system of cables leading to somewhere, but as a

network of relations. Rudy, Memo, and Memo’s father form a

network of relations operating within and outside of the

techno-rationality of the network. Referring again to my own

experience shared earlier, I think about how the ethical choice I

made to engage deeply in a network of relations with children and

families was a response to the address placed on me by the Other, and

how it also created nodes of ethical relationality in the network

that were unrecognizable to the licensing inspector.

Zylinska’s

(2014) use of the word network in relation to the concept of a

node, however, still echoes a sense of the scientific and technical.

I want to trouble further this by intersecting with Ingold’s

(2011) thinking of meshwork and knots to reposition and situate nodes

as more than static and organized points of connection. For Ingold

(2011) networks evoked images of efficient points of connection that

one can be connected to and may be entered into from various points

or nodes in the network. A meshwork, however, is much less organized,

technical, and predictable than the concept of a network suggests.

Ingold (2011) also envisioned a meshwork as storied and thus

relational:

It

is a world of movement and becoming, in which any thing—caught

at a particular place and moment—enfolds within its

constitution the history of relations that have brought it there. In

such a world, we can understand the nature of things only by

attending to their relations, or in other words, by telling their

stories. Indeed, the things of this world are their stories,

identified not by fixed attributes but by their paths of movement in

an unfolding field of relations. Each is the focus of ongoing

activity. Thus, in the storied world, things do not exist, they

occur. Where things meet, occurrences intertwine, as each becomes

bound up in the other’s story. (p. 199)

Ingold’s

(2011) meshwork conjures sensorial images of looped and knotted

string or rope entangled together and instead of nodes he thought

with knots. In fact, node and knot both originate from the Latin

nodus (Etymology online, n.d.). Where a node is a point of

connection in a network that one can connect into (and disconnect

from) as illustrated in the imagery in Sleep Dealer (2008), a

knot in a meshwork gives the feeling of a deeper processual

permanence. The meshwork is created through the making of knots

and/as stories in and with the work. The human is thus repositioned

in relation with the storied knots in the meshwork. The human’s

place in the meshwork is also contingent on their relations and the

stories that are woven together through their relations. In this way

the meshwork then makes space for “uncertainty and ambivalence”

(Dahlberg & Moss, 2005, p. 56) as well as for variability and

unpredictability. To create a meshwork requires trust and “relations

across difference” (Todd, 2003, p. 3) that respond to the

ethical and political in human and more-than human relations. What

would it mean to recognize the knotted and storied meshworks in ECE

that interrupt coded and technical networks? Or to take up Dahlberg

and Moss’s (2005) concept of “children’s spaces”

or “meeting places … where the coming together of

children and adults, the being and thinking beside each other, offers

many possibilities” (p. 28), as not just physical spaces but

also social, cultural, and discursive spaces where stories are woven

together into the fabric of democracy. Might it reassert the ethical

into early childhood practice as professionalism?

Everyday

ECEs encounter the radical alterity and otherness of the children and

families they share spaces with. They are story tellers with children

and families, attuned to and continuously co-creating conditions of

relationality and care, yet the storied meshworks of their relations

are continually reshaped and fitted into techno-rational networks of

accountability and compliance and node-ified ethics. Like my own

story of non-compliance, I had no longer accepted this reshaping of

my practice, the counting of my work only as the recognizable program

plan instead of an impromptu trip to the park. Our collective call to

activism is to reassert the ethical in early childhood education by

recognizing and valuing the knotted and storied meshworks of

educators that already exist, and to support them with the

professional pay and working conditions that provide them with the

time and space needed to engage in the ethical relations that blow up

coded and technical networks.

In

this article, I have taken up Tuck’s (2018) question of “How

shall we live?” (p. 157) to problematize the ethical in codes

of ethics in ECEC. I began by situating codified ethics within the

broader context of professionalization in Ontario and internationally

and offering a critique of how professionalism has not brought ECEs

the promised material recognition they were seeking but has rather

resulted in more regulation. Drawing on Todd (2003), I took up a

philosophical critique of codified ethics and explore her invitation

to rethink ethics in education as an ethical relationality. I then

weave together Dahlberg and Moss’s (2005) analysis of

neoliberalism’s creation of early childhood educator as a

worker-technician, the College of ECE’s Code of Ethics and

Standards of Practice and my own experience as an RECE along with the

aesthetic device of nodes in the dystopian film Sleep Dealer

(Rivera, 2008), to explore how codified ethics, as they become

enforceable within a regulatory body such as the College of ECE,

instrumentalize and dematerialize the early childhood educator.

Finally, in conversation with Zylinska and Ingold, I repositioned

nodes and networks as knots and meshworks and offer this article as

both a warning and a call to activism to reposition the ethical and

relational as central to early childhood education, to nurture not

only the lives of children and families but also the ethical,

political, and liveable futures of early childhood educators.

References

Association

of Early Childhood Educators Ontario (AECEO). (2008). Code of ethics.

ECE Link, Winter 2008.

Association

of Early Childhood Educators Ontario (AECEO). (2010). AECEO history:

A review of our milestones. ECE Link, Fall, 2010.

Association

of Early Childhood Educators Ontario (AECEO). (2016). “I’m

more than ‘just’ an ECE”: Decent work from the

perspective of Ontario’s early childhood workforce.

https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/aeceo/pages/930/attachments/original/1477442125/MoreThanJustanECE_Sept16.pdf?1477442125

Australian

Early Childhood Association. (1990). Code of ethics.

Cannella,

G. F. S. (1997). Deconstructing early childhood education: Social

justice and revolution. Peter Lang.

Flanagan,

K., Beach, J., & Varmuza, P. (2013). “You

bet we still care!” A survey of centre-based early childhood

education and care in Canada:

Highlights

report.

Child Care Sector Human Resources Council.

https://childcarecanada.org/documents/research-policy-practice/13/02/you-bet-we-still-care

College

of Early Childhood Educators. (2017). Code

of ethics and standards of practice, (2nd

ed.).

https://www.college-ece.ca/members/standards-in-practice/

Dahlberg,

G., & Moss, P. (2005). Ethics and politics in early childhood

education. Routledge Falmer.

Doherty,

G., Lero, D., Goelman, H., LaGrange, A., & Tougas, J. (2000). You

bet I care. A Canada-wide study on wages, working conditions and

practices in child care centres. Centre for Families Work and

Well-Being, University of Guelph.

Durham

College. (2022, May 24). College

now accepting applications for compressed early childhood education

program.

https://educationnewscanada.com/article/education/level/colleges/2/962463/college-now-accepting-applications-for-compressed-early-childhood-education-program.html

Early

Education. (2011). Code of ethics. British Association for

Early Childhood Education.

Feeney,

S., & Kipnis, K. (1989). A new code of ethics for early childhood

educators: Code of Ethical Conduct and Statement of Commitment. Young

Children, 45(1), 24–29.

George

Brown College (2022, October 17). GBC

launches new early childhood education (compressed) program to

address challenges in the ECE sector.

https://www.georgebrown.ca/news/2022/gbc-launches-new-early-childhood-education-compressed-program-to-address-challenges-in-the-ece-sector

Ingold,

T. (2011). Being alive. Routledge

Johnston,

L. (2019). The (not) good educator: Reconceptualizing the image of

the educator. ECE Link, Fall 2019. Association of Early

Childhood Educators Ontario.

Jones,

A. (2022a, May 22). Childcare

affordability leads to questions of space creation in Ontario

election. The

Canadian Press.

https://www.thestar.com/politics/2022/05/22/child-care-affordability-leads-to-questions-of-space-creation-in-ontario-election.html

Jones,

A. (2022b, October 8). As

childcare expands in Ontario, advocates wonder who will staff those

spaces. The

Canadian Press.

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/ontario-childcare-workforce-1.6611088

Katz,

L. (1984). The professional early childhood teacher. Young

Children 39(5), 3–10.

Langford,

R., Prentice, S., Albanese, P., Summers, B., Messina-Goertzen, B., &

Richardson, B. (2013). Professionalization as an advocacy strategy: A

content analysis of Canadian child care social movement

organizations’ 2008 discursive resources. Early

Years, 33(3),

302–317. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2013.789489

Levinas,

E. (1989). Ethics as first philosophy. In S. Hand (Ed.), The

Levinas reader: Emmanuel Levinas (pp. 75-87). Basil Blackwell

Ltd.

Lichtenberg,

J. (1996). What are codes of ethics for? In M. Coady & S. Block,

(Eds.), Codes of ethics and the professions (pp. 13–27).

Melbourne University Press.

National

Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC). (1998). Code

of ethical conduct and statement of commitment (Rev. ed.)

[Brochure].

Online

Etymology Dictionary. (n.d.). Node. Retrieved December 14, 2022 from

https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=node

Ontario

College of teachers (2022). Ontario regulatory body fees. Ontario

regulatory bodies membership fee comparison: 2021 membership year

https://www.oct.ca/members/college-fees/ontario-regulatory-body-fees

Osgood,

J. (2006). Deconstructing professionalism in early childhood

education: Resisting the regulatory gaze. Contemporary Issues in

Early Childhood, 7(1), 5-14. doi:10.2304/ciec.2006.7.1.5

Oxford

University Press. (n.d.). Dematerialize. In Oxford

English Dictionary (OED) Online. Retrieved

December

5, 2022 from www.oed.com/view/Entry/49605

Popkewitz,

T. (1994). Professionalization in teaching and teacher education:

Some notes on its history, ideology, and potential. Teaching &

Teacher Education, 10(1), 1–14.

Rivera,

A. (Director). (2008). Sleep dealer [Film]. Likely Story.

Saracho,

O.N., & Spodek, B. (1993). Professionalism and the preparation of

early childhood education practitioners. Early Child Development

and Care, 89, 1-17

The

Office of Early Childhood Education—Te Tari Mātauranga

Kōhungahunga. (2022, January). Code of ethical conduct.

https://oece.nz/public/information/ethics/code-of-ethical-conduct/

Todd,

S. (2003). Learning from the other: Levinas, psychoanalysis and

ethical possibilities in education. State University of New York

Press.

Tuck

E. (2018). Biting the university that feeds us. In M. Spooner &

J. McNinch (Eds.), Dissident knowledge (pp. 149–167).

University of Regina Press.

Urban,

M., Vandenbroeck, M., Van Laere, K., Lazzari, A., & Peeters, J.

(2012) Towards competent systems in early childhood education and

care: Implications for policy and practice. European Journal of

Education, 47(4), 508–526.

Zylinska,

J. (2014). Minimal ethics for the Anthropocene (1st ed.). Open

Humanities Press.

Endnote