“With Fear in Our Bellies”: A Pan-Canadian Conversation With Early Childhood Educators

Christine Massing, University of Regina

Patricia Lirette, MacEwan University

Alexandra Paquette, Université du Québec à Montréal

Authors’ Note

Christine Massing https//orcid.org/0000-0002-8518-9628

Alexandra Paquette https//orcid.org/0000-0003-2723-2656

We greatly appreciate the thoughtful participation of the early childhood educators whose contributions to the project were invaluable. Working collaboratively with colleagues from eight institutions across the country on the “Snail Project” has enriched our perspectives on childcare in Canada and we are grateful for the opportunity to co-inquire with the other members of the group. This project was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and the Centre for Educational Research, Collaboration, and Development at the University of Regina. We also thank the following institutions for their support: Seneca College, Thompson Rivers University, Université du Québec à Montréal, Université du Québec en Outaouais, the University of British Columbia, the University of New Brunswick, and the University of Regina.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Christine Massing, Faculty of Education, University of Regina, 3737 Wascana Parkway, Regina, Saskatchewan. Email: Christine.massing@uregina.ca

________________________

In spite of decades of advocacy and a number of intermittent stops and starts, until recently there has not been any sustained movement toward a national coordinated approach to early childhood education and care (ECEC) services in Canada (Bezanson, 2018). ECEC in Canada has been described as a patchwork of unplanned and often inadequate services across most jurisdictions; including a mix of regulated and unregulated, for-profit and non-profit programs (Friendly et al., 2016), thus negatively impacting families’ access to high-quality, affordable childcare (Langford et al., 2016). In spite of modest increases, there are only regulated spaces for fewer than a third of Canadian children aged five and under, which disproportionately affects newcomer and low-income families (Childcare Resource and Research Unit, 2021; Findlay et al., 2021; Massing et al., 2020). Concomitant with the high demand for spaces, fees continue to be high, particularly in locations with market/demand-based fees charged by for-profit centres rather than supply side fees set and funded by the provincial government (Macdonald & Friendly, 2021).[1]

Situated within this context, a group of academics from eight universities across Canada conceptualized the Sketching Narratives of Movement Towards Comprehensive and Competent Early Childhood Educational Systems Across Canada project, which received knowledge mobilization funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada in March 2020. The overarching purpose of our project was to learn about the innovative changes and practices in ECEC policy, practice, and pedagogy that have been enacted across provincial/territorial boundaries in diverse communities in conversation with educators, policy makers, advocates, academics, and knowledge keepers. Their expertise, as operationalized through existing and emerging local change narratives, was shared during a series of webinar events and then disseminated via our project website: https://ecenarratives.opened.ca. It was our hope that these narratives would inform the eventual development of a universal, competent[2] system of public ECEC in Canada. Early in the project, however, the ECEC landscape shifted again in two significant ways: first, by the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020 (World Health Organization, 2020), and second, by the Canadian federal government’s announcement on September 23, 2020 that it would be striking agreements with the provinces and territories to create and fund a national 10-dollar-a-day childcare system (Government of Canada, 2021).

In view of these changes, we immediately sought to amplify the voices of frontline early childhood educators from urban and rural communities across the country to better understand their experiences during a time of unprecedented upheaval in the sector. We held a pan-Canadian webinar conversation on November 21, 2020. This paper will explore the narratives which emerged when nine early childhood educators from across Canada were invited to share their lived experiences in response to prompts emerging from the broad question “what does it mean to be an early childhood educator at this time?” We foreground the voices of these educators as expressed through four interwoven and intersecting narratives; loss, sacrifice, adaptation and hope.

Literature Review

ECEC Workforce in Canada

It is widely recognized that a skilled, professionally prepared, and well-compensated ECEC workforce is critical to the positive life trajectories of children (McDonald et al., 2018), yet this goal has not yet been realized in the Canadian context. The ECEC workforce is decidedly gendered (more than 95% identify as women), economically disadvantaged, and culturally diverse with 33% being immigrants or non-permanent residents, and 5% from First Nations, Métis, or Inuit backgrounds (Frank & Arim, 2021; Uppal & Savage, 2021). As in many countries, there is a distinct separation between teachers who work in school contexts and early childhood educators who are employed in preschools, childcare centres, and other early learning settings (Beach, 2013). Formal educational requirements for professional certification vary from province-to-province, ranging from a single orientation course to a post-secondary diploma. Although current figures indicate that 71% of Canadian educators have a post-secondary education (Uppal & Savage, 2021), they still earn substantially less than teachers in the school system with a Canadian median income of less than $20 an hour (Childcare Resource and Research Unit, 2021; McQuaig et al., 2022). The general lack of public respect for ECEC as a profession, reflected in the poor compensation offered, represents a longstanding barrier to educator recruitment and retention (McQuaig et al., 2022). Although the emergence of the pandemic did renew interest in childcare policy and its importance to the national economy (Smith, 2021), this emphasis did not translate to enhanced working conditions, but rather served to further exacerbate these workforce issues.

According to a national survey, the pandemic prompted an immediate shutdown of 92% of childcare services, and 71% of centres reported staff layoffs (Vickerson et al., 2022). Government responses varied between and within different jurisdictions depending on provincial and territorial funding policies (Friendly et al., 2021; Richardson et al., 2021). Many childcare programs were subsequently re-opened, though, to care for the children of essential workers and/or the general public (Uppal & Savage, 2021). Educators were then labelled as “essential workers” themselves, and were expected to quickly respond to new imposed health protections including social distancing, enhanced hygiene practices and health protocols, cohort size limits and, for some, a rapid transition to online learning. Smith (2021) noted that the burden of sustaining unclear and sometimes conflicting governmental strictures and guidelines was downloaded on centres, leading to inequalities within the field. According to one Quebec study, educators working on-site reported lower levels of well-being and higher stress levels as compared with educators who were working remotely (Bigras et. al., 2021). Participants in Smith’s (2021) study in British Columbia likewise spoke of high levels of anxiety and stress due to the continued lack of resources and their concern for keeping the children safe. They noted a stark contrast in the acknowledgement of their efforts versus those of other essential workers who were celebrated by the public early in the pandemic. Vickerson et al.’s (2022) national survey indicated that educators were discouraged when they were not prioritized for vaccines, which they perceived as further evidence that they were undervalued and unappreciated. Next, we review the literature on professionalism to further contextualize the nuances around educators’ marginalized positioning.

Professionalism

Varied and contested constructions of the professional ECEC educator are evidenced by the perceived divisions between the educative and care functions of their work (Harwood et al., 2013; Moss, 2006; Osgood, 2010; Van Laere et al., 2012). Neoliberal accountability and standardized quality measures reflect a techno-rationalist privileging of the educative role of the early childhood professional bolstered by Eurocentric child development theories (Cannella, 1997). In contrast, care work has been associated with domesticity and femininity, rendering it “natural” and positioning educators as mother substitutes rather than as knowledgeable and skilled professionals (Langford, 2019; Osgood, 2006; Taggart, 2016). The concept of emotional labour (Hochschild, 1983) compels educators to manage any outward appearance of work-related emotions in the professional setting. In the ECEC setting, displays of affect or emotion in the classroom are deemed inappropriate even though work with children is complex, relational, and messy (Madrid & Dunn-Kenney, 2010). Paradoxically, educators are often envisioned as “unprofessional” when referencing the emotional aspects of their work, yet positioning their labour in the sphere of care justifies their low salaries and poor working conditions (Colley, 2006; Moyles, 2001). Recognizing that love, emotion, passion, and emotional intelligence are integral to work with young children has prompted some scholars to advocate for ways to mobilize them as political tools to enhance educators’ professional standing (Dalli, 2008; Fairchild & Mikuska, 2021; Harwood et al., 2013).

Recent perspectives on professionalism further attend to the shifting, fluid, and contextual nature of the educators’ work amidst these competing, universalist discourses. Dalli et al. (2012) defined professionalism as, “something whose meaning appears to be embedded in local contexts, visible in relational interactions, ethical and political in nature, and involving multiple layers of knowledge, judgement, and influences from the broader societal context” (p. 6). Studies have shown that educators do not blindly adhere to the dominant discourse, but rather reconceptualize their practice by drawing on their own practical and cultural knowledges to respond to the specific children in their care. For instance, Fenech et al. (2010) posited that educators exercise agency in problematizing the dominant “professional habitus” (Urban, 2008, as cited in Fenech et al., 2010) through reflection, collaboration, and meaning-making. Morris (2021) and Page (2018) found that educators subverted externally imposed rules and regulations when they believed that physical affection and relational care were necessary and beneficial. Immigrant educators in Massing’s (2018) study likewise defied normative mealtime practices when they were concerned for a child’s well-being. Therefore, educators do disrupt normative ways of being a professional as they negotiate with their own beliefs and judgments in relation to localized, contextual factors. The pandemic, however, represented a significant shift in the landscape of practice.

Theoretical Framework

This paper is situated within a framework of critical theory, which has an emancipatory goal of disrupting the systemic barriers which contribute to the disempowerment of marginalized groups in order to effect change (Apple, 2004; Darder et al., 2009). Educational institutions such as ECEC programs function as sites reproducing neoliberal, dominant ideologies and socialization goals (Giroux, 1997). During the pandemic, educators were designated as essential workers to facilitate the continued participation of parents in the paid labour market. This language hinted at possible disruptions to existing power structures as manifested in the inadequate pay, recognition, working conditions experienced by educators. Yet emerging workplace realities required educators to respond to unprecedented pandemic conditions in a fragile non-system with a still-underpaid and undervalued status preserved by an economic, capitalist discourse. Educators were also bound to new, externally-imposed public health and safety strictures, thus further eroding their professional autonomy.

This project is grounded in the contention that the planning and development of a national plan for childcare must foreground the perspectives of those on the front line working with children and families. The knowledge mobilization activities became a way to enhance the collective development of conscientizaçao or critical social consciousness through engagement in dialogue and reflection (Darder et al., 2009; Freire, 1990; McLaren, 2007). The webinars functioned as dialogical spaces wherein viewers, facilitators, and panelists learned from one another; fostering a deeper understanding of the realities of working in ECEC, in the past as well as in the present moment, to develop co-intentionality as related to possibilities for social action (Freire, 1990). The website was constructed to advance a space in which to engage in further conversation. Zembylas (2013, 2021) invited us to interrogate how emotion and affect, dimensions embedded within (post)traumatic contexts, are multifaceted, critical elements in any struggle for change. These spaces, then, should allow interlocutors to dwell within the discomfort, applying emotional effort to listening to one another and discussing both “the potential and the harm that troubled knowledge stimulates” (Zembylas, 2013, p. 184). According to Zembylas (2013), the mutual experience of mourning and loss, and concomitant feelings of vulnerability, can foster a sense of connection. By centring the voices and experiences of educators typically marginalized or silenced in the dominant discourse of ECEC, therefore, we hoped to co-create a counter-hegemonic space of resistance while simultaneously documenting educators’ micro-acts of resistance in practice (Darder et al., 2009; Giroux, 1997; Zembylas, 2021).

Methodology

Consistent with the overall project goal of bringing together ECEC policy makers, educators, activists, and researchers to create communities of inquiry, we planned a series of three bilingual webinars with the following groups of panelists: policy experts/academics, early childhood educators, and international experts. Originally intended to be broadcast live to in-person groups gathering on campuses across the country, the pandemic shifted our conversations to Zoom and participants utilized the chat function to engage with one another and with the panelists. In this paper, we focus on the second webinar, a 2-hour event held on November 21, 2020. The agenda included a territorial acknowledgement, introductions, discussion questions and responses, a question-and-answer period, and closing comments. The panel was bilingually moderated by two research team members, and a professional translator provided live captioning in French. The recorded webinar was then reviewed by one of the team members for accuracy in French captioning, uploaded to YouTube, and linked to the project website. We also invited the national ECEC community to share their thoughts via photo collages posted on our project website.

Participants

The participants were selected using convenience sampling with the goal of assembling a pan-Canadian panel with diverse representation in terms of experience, gender, geographical location, role, and ethnocultural background. Members of our project team reached out to contacts in our networks to locate early childhood educators who would be interested in participating in a panel discussion. All of the participants were fluent in English, though they could participate in the discussions using either English (n = 8) or French (n = 1) according to their preferences. Table 1 summarizes our participant information:

Table 1

Participant Information

|

Name |

Location |

Role |

|---|---|---|

|

Janice |

Vancouver, British Columbia |

Educator in an inclusive education centre |

|

Daniel |

Vancouver, British Columbia |

Substitute educator in two childcare centres and ECEC college instructor |

|

Christina |

Northwest Territories |

Junior kindergarten/kindergarten/Grade 1 teacher |

|

Brittany |

Edmonton, Alberta |

Manager of an ECEC lab school attached to a university |

|

Safaa |

Regina, Saskatchewan |

Preschool teacher in a program for low-income families |

|

Mallory |

Six Nations Territory |

Educator in an on-reserve childcare centre until the pandemic |

|

Song |

Toronto, Ontario |

Educator at an ECEC drop-in centre, switched to remote deliver tutoring during pandemic |

|

Véronique |

Montreal, Quebec |

Educator at a childcare centre |

|

Kristina |

New Brunswick |

Educator and assistant director |

Methods

Procedures

An organizational meeting was held with participants 1 week prior to the live webinar to meet each other, gain familiarity with the digital platform, and co-develop the questions. The educators generated questions related to their work with children and families during the pandemic, different ECEC narratives circulating during the pandemic, additional narratives that need to be told, and possibilities for meaningful change. At the meeting, the educators were given an opportunity to view the photo-collage submissions and were asked to select one which resonated with them to speak to during the webinar.

Data Collection and Analysis

The data for this paper were derived from the video transcriptions and artistic data in the form of photo collages. Each of the panel participants signed a media release agreeing that we could record the webinar and share it publicly on YouTube and be linked to our project website. “The Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans” (Government of Canada, 2018) would classify this recording as being in the public domain, thus the participants would have “no reasonable expectation of privacy.” With their permission, their full names were included in the presentation and publicly available video. Yet, we were cognizant of the ethical tensions around the subsequent use of the data for this paper, acknowledging that “expectations of privacy are ambiguous, contested, and changing” (Markham, 2012, p. 336, as cited in Patterson, 2018). We consequently asked participants to let us know if they objected to their comments being included in this paper and if there was anything they wanted to add, change, or delete. Participants who shared photo collages signed a release.

Three members of the research team reviewed the webinar transcript and collages individually, doing multiple readings line-by-line, jotting down notes to generate possible descriptive codes, and writing analytic memos (Gibbs, 2007; Saldaña, 2012). We then met as a group to refine the codes and define the parameters for each one. Individual team members engaged in focused coding, reviewing the transcript carefully to apply codes, and then comparing their work with others. Finally, similar codes were combined to formulate broad themes which are shared as narratives in the section that follows.

Findings

The themes are organized into overlapping and intertwined narratives, including loss, sacrifice, adaptation, and hope. We intentionally highlight educators’ voices to value and centre the important personal and professional insights, feelings, decisions, and desires that they risked sharing with us and with the audience.

Narratives of Loss

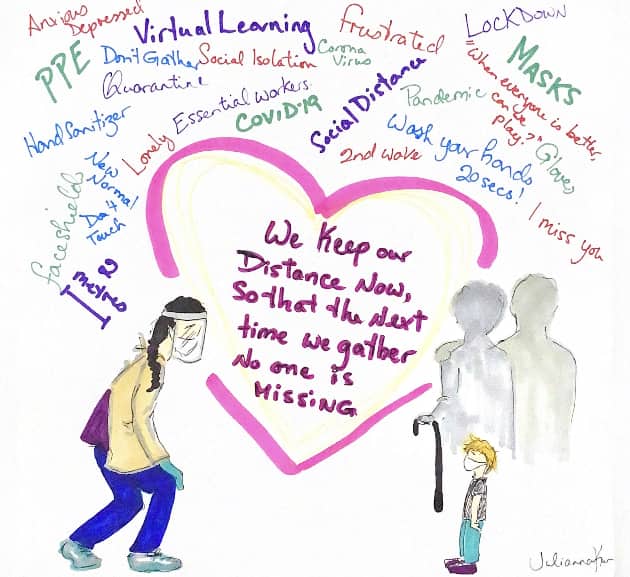

What we are describing as “narratives of loss” was manifested primarily as educators’ overwhelming concern about losing their connections to and relationships with children and families, but also as a loss of certainty and professional autonomy in their day-to-day work. This photo collage submission (Figure 1) portrays the overarching narrative of loss and fragments of thoughts and feelings evoked by the new reality of working and living with COVID-19.

Figure 1

“We Keep Our Distance” Photo Collage

In response to this image (Figure 1), Brittany was reminded of a child telling her that they could not spend Christmas with their grandparents due to the introduction of limits on social gatherings. She said:

I was really very emotional when [that] happened and I am still emotional about it now and this image brought that to my attention … it is a reminder once again about the responsibility I feel to ensure that I am doing everything I can for quality engaging programming and keeping it safe so that these children do get to see their grandparents again.

The loss of daily and in-person connections resulted in feelings of sadness and grief as educators mourned their disappearing and diminished connections, relationships, and communities. Song stated:

Being an early childhood educator during this time is not easy and especially our job in general. We are a person who develop community, a person who support the whole family, a person who cares for those vulnerable children, right? At this point I think the most challenging thing for myself is how do we keep and stay connected with family? Those meaningful and valued connections become remotely [sic], become two metres apart, become almost impossible in some centres.

He recalls one incident that made him particularly emotional:

A girl’s dad sent me a message, [saying] “Song, it’s not fair that the kids get to see you but you don’t get to see the kids.” So, he sent me a photo of [his child] touching the [computer] screen, trying to touch my face. That made me cry.

Enforced separation and distancing thus evoked an emotional response, emphasizing the tensions between emotional labour and professionalism. Educators were expected to perform emotional work, while remaining professionally detached, though Song’s example underscores how difficult it was to cope with loss while being expected to maintain restraint and composure. This emotional toll, alongside an expectation to act professionally, was evident in their narratives. Educators worried that the imposed health protections would affect the nature of the care they normally provided and what that would mean for children. As Brittany described: “The stress and the worry and the compliance that sits on educators’ shoulders is so heavy right now.”

As the ground shifted beneath their feet, some educators spoke to their loss of a sense of certainty, a mourning of a previous sense of self and how they used to do things. For example, in one photo collage an educator wrote: “Being an ECE means to me happiness, joy, patience, and a good sense of humour. In this current moment, I am feeling lonely in a big world and unable to teach children in a way I am used to.”

We observed educators actively negotiating and revisiting what it meant for them as professionals if they could not practice in ways that mattered to them. They described having to implement extraordinary changes to practice, changes that prioritized increased hygiene practices over pedagogy and required increased surveillance of children’s play and interactions. As Safaa described:

So many things in our classrooms have changed, for example, now [we] only allow for two or three children playing at the same station at the same time. We had to cancel many big activities to help children maintain social distance, [and] we have also stopped encouraging children to share toys or personal things. We also had a big challenge of getting children to wear face masks…that was so hard.

Their words suggested how uncomfortable and constraining practice in a pandemic felt; however, they had little choice but to comply with imposed directives for the sake of children’s safety. Therefore, they were “simultaneously resenting and enacting the selfless role presented to them” (Taggart, 2011, p. 90).

Narratives of Sacrifice

When the role of the educator is disproportionately positioned as a maternalistic, custodial one, it implies sacrifice; giving up something (or oneself) for the sake of another (Online Etymology Dictionary, 2022). Early in the pandemic, educators were ostensibly anointed as essential workers, as discussed by Safaa: “We kept our centres open…to welcome the children of frontline workers, including doctors and nurses and police officers.” Yet it soon became evident that, unlike other essential workers who garnered wage increases or applause on the streets, the systemic conditions and barriers that have functioned to undervalue educators’ labour were to be upheld. They were expected to carry on for the sake of the economy without adequate financial compensation or respect for their work, while enduring additional challenges. Daniel described being told they were essential while “being treated like we’re disposable.”

Echoing a common sentiment, Kristina asserted that surrendering their own sense of safety for the sake of families was deserving of some form of recognition:

Like we are there providing this service, this job, and it needs to be valued ... it’s not just so you can go do the more important work and we’ll just be over here doing this [providing childcare] ... and the fact that financially we are not compensated nearly enough for what we do and the vulnerable position we are putting ourselves in ... remaining open so that families can go out to work ... there is a huge disconnect there on what does that actually mean [to be an essential worker].

Passion and love for one’s work is not sufficient to pay the bills, Janice argued, particularly in expensive cities like Vancouver, where working two or three jobs is a necessity.

Integral to this narrative of sacrifice is the notion that educators will put the needs of others above their own, maintaining their professional standards even as working conditions shifted and demands increased. At a time when little was known about the virus, they forwent their own sense of security and well-being for the sake of the children, as shared by Véronique:

|

On s’est rendu au travail, dans une ville fantôme … la peur au ventre, on savait pas à quoi on avait affaire, c’était quoi le virus, … est-ce qu’on allait tomber malade, est ce qu’on allait travailler avec des enfants qui sont malades ... Nous avons mis toutes nos incertitudes, nos peurs, notre incompréhension de côté, puis on a été travailler sans hésiter. …

Être éducatrice s’est être épuisée par les tâches connexes qui s’ajoutent et savoir que le moindre manque de vigilance ou de patience de notre part va avoir un impact sur les enfants. |

We were on our way to work, walking through a ghost town … with fear in our bellies wondering what kind of virus we were dealing with, … were we going to get sick or the children we work with … We put all of our uncertainties, our fears, our lack of understanding aside and we went to work without hesitation. …

Being an educator means being exhausted by the numerous related tasks being added and knowing that the slightest lack of vigilance or patience on our part is going to have an impact on the children. |

The following photo collage (Figure 2) is symbolic of this tension between sustaining their dedication to the children and taking care of themselves:

Figure 2

“Burning on While on the Edge of Burning Out” Photo Collage

Educators were thus compelled to suppress their own fears and emotions to maintain safe conditions for the children, while applying their own professional expertise to the task of adapting to a new and constantly shifting set of policies and procedures.

Narratives of Adaptation

During the pandemic, educators had to adapt to a crisis of unknown proportions and the changing measures that it implied. They described finding new ways of working in ECEC while navigating professional practice in a constantly shifting context. In spite of the constraints, workload intensification, and their own fears, the educators maintained their dedication and commitment, persevering in their work with the children. As Véronique explained:

|

Nous avons continué à le faire même quand le contexte de pandémie nous demandait de plus en plus de travail et de vigilance. Pendant le déconfinement progressif, nous avons dû nous adapter à des charges de désinfection, de bulles sociales, de manque de personnel en plus de notre mandat habituel de pédagogie, de planification et de soutien aux enfants. |

We continued to do so even when the pandemic context demanded more and more work and vigilance from us. During the lifting of lockdown measures, we had to adapt to lots of disinfection, social bubbles, lack of personnel in addition to our usual mandate of pedagogy, planning, and support for children.

|

Educators admitted that they were faced with unprecedented challenges that left them feeling unprepared and needing to learn and implement new skills and strategies. During the mandated program closures, they reflected on ways to prepare children for their eventual return to the childcare program. They invented various means to stay connected with children, families, and staff, including shifting to eLearning platforms; holding zoom meetings; streaming live story time; and creating videos, websites, and FaceBook pages. Moreover, some implemented weekly phone calls to children’s homes; held driving parades; shifted to outdoor dismissal; organized socially distanced outdoor gatherings and celebrations; as well as delivered activity packages, meals, or food hampers. All these examples illustrated the enormous amount of energy and creativity in devising strategies and pedagogical practices as they attempted to minimize and normalize the conditions imposed by the pandemic.

Another form of adaptation that emerged from our analyses as educators endeavoured to approach the pandemic from a positive perspective, citing it as an opportunity for reflection and professional regeneration. Mallory summed up this notion as follows:

As an ECE, I believe it is our responsibility to challenge ourselves and to expand our own learning and to adapt to the new experiences and really try to take this as a learning opportunity to better ourselves and to better our practice.

The photo collage (Figure 3) which follows implies that educators were committed to making the best of their new work reality:

Figure 3

“Making Lemonade Out of Lemons” Photo Collage

Christina’s reaction to the collage similarly suggested optimism:

Although we don’t necessarily get to have the same experiences we’ve had in the past or get to do things the same way, it doesn’t mean that we can’t create new experiences and still find new ways to learn, adventure, and explore, and adhere to the restrictions we all face ... [while] making new memories.

Brittany also conveyed positivity when she described how the pandemic reaffirmed the importance of listening to children and capturing the moment. She said, “We need to be recording ... [so we can] say we moved out on the other end of this over here in this new space and that's what it was like.” She then concluded, “The children are speaking to us through their play and it’s our job to listen.”

A shift in professional role is articulated by Song when he talks about his newly learned ability to navigate online platforms (Figure 4).

Figure 4

“How Many Tabs/Apps Can an ECE Fit on One Screen?” Photo Collage

Song explained how the pandemic brought many challenges and with it the necessity to learn new skills. He described how the ECEC community was determined to learn them in order to stay connected. To him, the fact that educators “jumped right into virtual learning without knowing anything” showed strength and he proclaimed himself to be “so proud to be a part of this community.” His sense of pride translates into a desire to do better, a hopeful look to the future, which we identified as the final narrative.

Narratives of Hope

Freire (1994) asserted, “Without a minimum of hope, we cannot so much as start the struggle. But, without the struggle, hope, as an ontological need, dissipates, loses its bearings, and turns into hopelessness” (p. 9). Ahmed (2015) added that hope “animates a struggle,”—in this case against the neoliberal agendas at play—and “carries us through when the terrain is difficult” (p. 2). Figure 5 elucidates how the despair, loss, and sacrifices of the pandemic and the current conditions in the sector are also accompanied by hope for possibilities and changing conditions.

Figure 5

“A New Generation of ECEs” Photo Collage

In describing feeling both discouraged and hopeful concurrently, the author of the poem in Figure 5 is not “glossing over” or erasing the emotional complexities of caring and responsibility, but instead is expressing a deeper reflective stance that exposes her awareness of how educator relationships are defined in relation to the broader political, social, and economic context (Cvetkovich, 2012, as cited in Zembylas et al., 2014). As Daniel acknowledged, hope is also derived in part from knowing they are being supported to enter a community with a long history of advocacy work undertaken by others who have come before (Friendly, 2009; Mahon, 2000; Pasolli, 2019):

Mentors and people who I think are giants in the field have sort of taken me under their wing for a brief period of time and I only hope that I have the opportunity to do that as well. ... I think of it more as a marathon where you run as long as you can and carry the torch and then when you are tired hopefully pass the torch to someone else.

Educators shared the hope that the federal funding announcement would lead to educators being valued, recognized, and acknowledged for their crucial role “in shaping future generations” (Kristina). Societal and political recognition, they anticipated, could bring additional funding, staff, and resources to the sector, leading to improved compensation and working conditions. Their aspirations for change in terms of the dominant discourses were evident in comments such as Daniel’s:

Even if childcare doesn’t affect you directly, it affects you indirectly. … When we continue to frame early childhood care and education only through the lens of the economy, we forget that, like Janice and me, [we] are working two jobs, you know, we forget that a lot of our ECEs are struggling to make ends meet.

The potential for a universal system also produced hope of a better future for families and children, as people “realize how important early childhood education is,” in Song’s words. Daniel sought to disrupt the overarching economic discourse: “I think when we frame it through the economy, and not through children’s rights and women’s rights and workers’ rights, we miss a big part of why we are so important.” Kristina emphasized, first and foremost, the significance of their work as advocates for young children who may not otherwise be heard:

We spent years developing our expertise in this field and for us to be able to bring the voice ... of children in 0 to 5 [programs] to the political world and say, like listen, we’re not just passing time. … Just for us to be able to continue to validate that and really drive it home—how crucial and how important it is that, you know, we live in the lives of these children.

Song invited educators to use social media and join coalitions and local organizations to help “consolidate our voice,” when he affirmed, “I want ECE’s to know the power of the profession, the power of advocating for the profession.”

Brittany envisioned an entirely new narrative flourishing within local communities of practice: “The narrative of thriving early childhood communities is one that needs to be told … the story of children returning to cherished spaces after closures or restrictions.” For her, the “magic and joy of children returning and seeing their educators and seeing their peers and reuniting after this time away is a beautiful story that speaks to what we do and that is a wonderful narrative that should be shared.” Furthermore, she stated, “We can embrace the joy that is play in community. That’s the narrative that is also unfolding alongside this [pandemic]. ... Children continue to play even though everything else is going on around them. I think this speaks to the level of work that ECEs are doing in the field.” She continued, “So, it makes me hopeful, yeah the power of relationships and being together in community.” Brittany’s new narrative presents as an example of resistance in practice (Darder et al., 2009), countering the hegemonic narrative of childcare as a means of salvaging the economy used by the government and promoted in the media as a rationale for a new system of childcare.

Discussion

For many educators, the pandemic was (and continues to be) a survival event; their previously well-known working environment suddenly became hostile, unwelcoming, and unfamiliar territory. In the already demanding context of their day-to-day work, COVID-19 enhanced the regulatory gaze governing educators via externally imposed regulations and requirements, which consequently led to workload intensification as well as a heightened awareness of the physically and emotionally risky nature of work, as they went “to work with fear in our bellies” for their own safety and that of their family members. The educators’ sense of professional autonomy or control over their workplace conditions and practices was thus subsumed by immovable and indisputable public health orders, seemingly leaving little space for them to draw on their own professional judgements. Ahmed (2015) theorized that articulations of love, grief, and mourning are intensified with the experience of loss. The educators’ stories spoke to their attempts to make meaning of their predicament as they mourned the way things once were and endeavoured to figure out what it meant for them as professionals if, as van Groll and Kummen (2021) noted, practice in the pandemic generated pedagogical and ethical tensions. As in other contexts, they especially grieved the loss of community and connection (Swadener et al., 2020). Their experiences of loss were inextricably linked to emotionality even though overt expressions of feeling have been deemed inappropriate and unprofessional in the techno-rationalist discourse (Osgood, 2010).

During the pandemic, the educators have been labouring under an increased culture of accountability that has further advanced governmental centralized control over practice in local contexts through the imposition of health and safety measures that constructed childcare centres as “safe” in order to keep them open (Osgood, 2010). Since the expectation of ensuring children’s safety was delegated to educators and centres, they were forced to assume increased responsibility without the corresponding recognition. Educators were ambivalent towards the new label of essential workers, as they felt they had been ignored, neglected, and sacrificed for “the sake of the economy.” The precarious nature of their work combined with their low pay and status fostered the exploitative conditions for what Tronto (2013) referred to as privileged irresponsibility, wherein the privileged could opt out of caring roles to pursue more lucrative economic activities while ignoring the fears and hardships experienced by educators/carers (Zembylas et al., 2014). Swadener et al. (2020) have asserted that “repairing this deeply fractured system requires the dismantling of the systems of oppression that have reinforced the disrespect and devaluation of the women (and men) who have always been essential” (p. 317). It was disheartening to them that even the pandemic did not legitimize or make their important work visible and, as in other studies, the additional worries and stress left them vulnerable to burnout, post-traumatic stress disorder, or mental health issues (Bigras et al., 2021; Gomes et al., 2021). Educators sustained their care for others even at a time when they themselves were not being cared for but rather were construed as expendable and disposable.

While confronted by many challenges, though, these educators, like many across Canada, pivoted, learned, transitioned, and reflected on their new roles, showing persistence and resilience in adapting to the crisis. Illustrative of the potential that troubled knowledges can stimulate (Zembylas et al., 2014), they strove to regain lost connections, albeit more distanced or virtual versions of those they once had, and to co-create new ways of being together. Within the confines of regulatory mandates, they located spaces wherein they could inflect their practice with their own understandings to make life better for children and families. Oosterhoff et al.’s (2020) research affirmed that when regulatory frameworks operated to manage and erode educator autonomy, aspects of their working conditions, such as support from colleagues, allowed them to productively harness their emotionality. Hokka et al. (2017, as cited in Oosterhoff et al., 2020) referenced the “transformative and sustaining power” of emotions “in the enactment of agency” ( p. 148). The educators did not engage in ethical subversion with respect to the new regulations (Morris, 2021) as these were aimed at child/educator protection, but rather navigated within them and practiced within their constraints to centre love and care for the children and to normalize conditions in extraordinary circumstances. While educators spoke to their fears, concerns, worries, and stresses, they also emitted pride, innovation, passion, optimism, and hope. These findings are thus suggestive of Osgood’s (2010) conceptualization of professionalism from within, which is socially constructed in a specific socio-political/economic time and location and legitimizes emotional practice as a counter-discourse to the regulatory frameworks. It provides further evidence of their personal and collective investments “in creating a culture of care characterized by affectivity, altruism, self-sacrifice, and conscientiousness” (Osgood, 2010, p. 126).

Finally, through engagement in dialogue and reflection, Freire (1990) spoke to the potential for the collective development of critical social consciousness. These educators were acutely aware of the oppressive conditions inherent in their field, the causes of such conditions, and their own positioning within hegemonic public/policy frameworks and discourses (Freire, 1990). They expressed both skepticism and optimism in relation to the development of a universal system in Canada, fearing that, in Fairchild and Mikuska’s (2021) words, “the promises of professionalization [will] do little to change the wider perspective of those both inside and outside the sector” (p. 1184). However, the webinar afforded them the opportunity to share their perspectives with a broader audience, mobilizing support for action. Fenech et al. (2010) have reminded us that professionals also cultivate a transformative ethic of resistance to practices which undermine their own expertise and are not in the best interests of the children. These acts of resistance need not be large in scope, as in the webinar, but rather may be relational micro-actions or interactions in the context of day-to-day experiences that work in opposition to dominant technical approaches. Consistent with Brittany’s comments, listening, engaging, and documenting in practice might become tools to centre children’s voices and make their perspectives visible in opposition to the discourses circulating by way of regulatory and policy documents.

Conclusion

The narratives the educators shared embodied the complex, multifaceted, and shifting nature of their lived experiences over the course of the pandemic. Osgood (2010) calls for “emotional professionalism to be celebrated rather than denigrated and obscured from public discourse” (p.131). The pandemic exacerbated the already existing gendered, classed, and racialized inequities and divisions of labour and enhanced the conditions creating privileged irresponsibility for some at the expense of educators (Tronto, 2013; Zembylas et al., 2014). The work of childcare educators during the pandemic and beyond requires recognition of the emotional complexities of caring and the increased demands being made. It foregrounds the consequences when the responsibility for care is not examined or prioritized. In this particular moment on the cusp of a new national system, we have an obligation to “unsettle the givenness” (Massey, 2005) of the dominant and perpetual discourses that trivialize and simplify the complex work of ECEC or that relegate childcare to an economic activity or commodity without thought to what it means to provide just and equitable life experiences to children, families, and educators. To resist a “prescriptive and narrow quantification” of the professional role of educators (Harwood et al, 2013, p. 11), it is imperative to provide space for the lived experiences, critical insights, and interwoven story lines offered by educators and children, as we attempt to mobilize for transformative change and social action in the development of a competent ECEC system in Canada.

References

Apple, M. (2004). Ideology and curriculum. Routledge.

Ahmed, S. (2015). The cultural politics of emotion. Routledge.

Beach, J. (2013). Overview of childcare wages, 2000-2010. Childcare Human Resources Sector Council.

Bezanson, K. (2018). Feminism, federalism and families: Canada's mixed social policy architecture. Journal of Law and Equality, 14(1), 169–97. https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/utjle/article/view/30894

Bigras, N., Lemay, L., Lehrer, J., Charron, A., Duval, S., Robert-Mazaye, C., & Laurin, I. (2021). Early childhood educators’ perceptions of their emotional state, relationships with parents, challenges, and opportunities during the early stage of the pandemic. Early Childhood Education Journal, 49, 775–787. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-021-01224-y

Cannella, G. (1997). Deconstructing early childhood education: Social justice & revolution. Peter Lang Publishing.

Childcare Resource and Research Unit (2021). Early childhood education and care in Canada 2019: Summary and analysis of findings. Childcare Resource and Research Unit. https://childcarecanada.org/sites/default/files/ECEC2019-Summary-Analysis.pdf

Colley, H. (2006). Learning to labour with feeling: Class, gender and emotion in childcare education and training. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 7(1), 15–29. https://doi.org/10.2304/ciec.2006.7.1.15

Dalli, C. (2008). Pedagogy, knowledge and collaboration: Towards a ground-up perspective on professionalism. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 16(2), 171–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/13502930802141600

Dalli, C., Miller, L., & Urban, M. (2012). Early childhood grows up: Towards a critical ecology of the profession. In L. Miller, C. Dalli, & M. Urban (Eds.), Early childhood grows up: Towards a critical ecology of the profession (pp. 3–19). Springer.

Darder, A., Baltodano, M., & Torres, T. D. (2009). The critical pedagogy reader. Routledge.

Online Etymology Dictionary (2022). Sacrifice. https://www.etymonline.com

Fairchild, N., & Mikuska, E. (2021). Emotional labor, ordinary affects, and the early childhood education and care worker. Gender, Work & Organization, 28(3), 1177–1190 https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12663

Fenech, M., Sumison, J., & Shepherd, W. (2010). Promoting early childhood teacher professionalism in the Australian context: The place of resistance. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 11(1), 89–105. https:///doi.org/10.2304/ciec.2010.11.1.89

Findlay, L. C., Wei, L., & Arim, R. (2021). Patterns of participation in early learning and child care among families with potential socioeconomic disadvantage. Government of Canada. https:///doi.org/10.25318/36280001202100800002-eng

Frank, K., & Arim, R. (2021). Indigenous and non-Indigenous early learning and childcare workers in Canada. Government of Canada. https://doi.org/10.25318/36280001202100800002-eng

Freire, P. (1990). Pedagogy of the oppressed. (M. Bergman Ramos, Trans.). Continuum.

Freire, P. (1994). Pedagogy of hope. (M. Bergman Ramos, Trans.). Continuum.

Friendly, M. (2009). Can Canada walk and chew gum? The state of childcare in Canada in 2009. Our Schools/Our Selves, 18(3), 41–55. https://policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/Our_Schools_Ourselve/OS_OS_95_Martha_Friendly.pdf

Friendly, M., Forer, B., Vickerson, R., & Mohamed, S. S. (2021). COVID-19 and childcare in Canada: A tale of ten provinces and theory territories. Journal of Childhood Studies, 46(3), 42–52. https://doi.org/10.18357/jcs463202120030

Friendly, M., White, L., & Prentice, S. (2016). Beyond baby steps: Planning for a national child care system. Policy Options. https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/july-2016/beyond-baby-steps-planning-for-a-national-child-care-system/

Gibbs, G. (2007). Analyzing qualitative data. SAGE.

Giroux, H. (1997). Pedagogy and the politics of hope: Theory, culture, and schooling. Westview Press.

Gomes, J., Almeida, S. C., Kaveri, G., Mannan,m F., Gupta, P., Hu, A., & Sarkar, M. (2021). Early childhood educators as COVID warriors: Adaptations and responsiveness to the pandemic across five countries. International Journal of Early Childhood, 53, 345–366. https:///doi.org/10.1007/s13138-021-00305-8

Government of Canada. (2018). Tri-council policy statement: Ethical conduct for research with humans. Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans – TCPS 2 (2018).

Government of Canada. (2021). Budget 2021: A Canada-wide early learning and childcare plan. https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/news/2021/04/budget-2021-a-canada-wide-early-learning-and-child-care-plan.html

Harwood, D., Klopper, A., Osanyin, A., & Vanderlee, M. (2013). ‘It’s more than care’: Early childhood educators’ concepts of professionalism. Early Years: An International Research Journal, 33(1), 4–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2012.667394

Hochschild, A. (1983). The managed heart. University of California Press.

Langford, R. (2019). Introduction. In. R. Langford (Ed.), Theorizing feminist ethics of care in early childhood practice: Possibilities and dangers (pp. 1–16). Bloomsbury Academic.

Langford, R., Prentice, S., Richardson, B., & Albanese, P. (2016). Conflictual and cooperative childcare politics in Canada. International Journal of Child Care and Education Policy, 10(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40723-016-0017-3

MacDonald, D., & Friendly, M. (2021). Sounding the alarm: COVID-19’s impact on Canada’s precarious childcare sector. Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. https://policyalternatives.ca/TheAlarm

Madrid, S., & Dunn-Kenney, M. (2010). Persecutory guilt, surveillance, and resistance: The emotional themes of early childhood educators. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 11(4), 388–401. https://doi.org/10.2304/ciec.2010.11.4.388

Mahon, R., (2000). The never-ending story: The struggle for universal childcare policy in the 1970s. The Canadian Historical Review, 81(s3), 825–853. https://doi.org/10.3138/chr-102-s3-013

Massey, D. (2005). For space (3rd ed.). SAGE.

Massing, C. (2018). African, Muslim refugee student teachers’ perceptions of care practices in infant and toddler field placements. International Journal of Early Years Education, 26(2), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2018.1458603

Massing, C., Kikulwe, D., & Ghadi, N. (2020). Newcomer families’ participation in early childhood education programs. Exceptionality Education International, 30(3), 25–42. https://doi.org/10.5206/eei.v30i3.13379

McDonald, P., Thorpe, K., & Irvine, S. (2018). Low pay but still we stay: Retention in early childhood education and care. Journal of Industrial Relations, 60(5), 647–668. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022185618800351

McLaren, P. (2007). Life in schools: An introduction to critical pedagogy in the foundations of education. Pearson.

McLaren, P. (2009). Revolutionary pedagogy in post-revolutionary times: Rethinking the political economy of critical evaluation. In A. Darder, M. Baltodano, & T. D. Torres (Eds.), The critical pedagogy reader (pp. 151–186). Routledge.

McQuaig, K., Akbari, E., & Correia, A. (2022). Canada’s children need a professional early childhood workforce. Atkinson Centre for Society of Child Development. https://ecereport.ca/en/workforce-report

Ministère de la Famille (2022). Childcare services. https://www.mfa.gouv.qc.ca/en/services-de-garde/Pages/index.aspx

Morris, L. (2021). Love as an act of resistance: Ethical subversion in early childhood professional practice in England. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 22(2), 124–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/1463949120932297

Moss, P. (2006). Structures, understandings and discourses: Possibilities for re-envisioning the early childhood worker. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 7(1), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.2304/ciec.2006.7.1.30

Moyles, J. (2001). Passion, paradox, and professionalism in early years education. Early Years, 21(2), 81–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575140124792

Oosterhoff, A., Oenema-Mostert, I., & Minnaert, A. (2020). Constrained or sustained by demands? Perceptions of professional autonomy in early childhood education. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 21(2), 138–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/1463949120929464

Osgood, J. (2006). Deconstructing professionalism in early childhood education: Resisting the regulatory gaze. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood Education, 7(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.2304/ciec.2006.7.1.5

Osgood, J. (2010). Reconstructing professionalism in ECEC: The case for the ‘critically reflective emotional professional’. Early Years: An International Research Journal, 30(2), 119–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2010.490905

Page, J. (2018). Characterizing the principles of professional love in early childhood and care. International Journal of Early Years Education, 26(2), 125–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2018.1459508

Pasolli, L. (2019, February). An analysis of the multilateral early learning and childcare framework and the early learning and childcare bilateral agreements. Childcare Now. https://muttart.org/an-analysis-of-the-multilateral-early-learning-and-child-care-framework-and-the-early-learning-and-child-care-bilateral-agreements/

Patterson, A. N. (2018). YouTube generated video clips as qualitative research data: One researcher’s reflection on the process. Qualitative Inquiry, 24(10), 759–767. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800418788107.

Richardson, B., Powell, A., & Langford, R. (2021). Critiquing Ontario’s childcare policy responses to the inextricably connected needs of mothers, children, and early childhood educators. Journal of Childhood Studies, 46(3), 3–15. https://journals.uvic.ca/index.php/jcs/article/view/19951

Saldaña, J. (2012). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. SAGE.

Smith, J. (2021). From “nobody’s clapping for us” to “bad mom”: COVID-19 and the circle of childcare in Canada. Gender, Work & Organization, 29(1), 353–367. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12758

Swadener, B. B., Peters, L., Frantz Bentley, D., Diaz, X., & Bloch, M. (2020). Childcare and COVID: Precarious communities in distanced times. Global Studies of Childhood, 10(4), 313–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043610620970552

Taggart, G. (2011). Don’t we care?: The ethics and emotional labour of early years professionalism. Early Years, 31(1), 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2010.536948

Taggart, G. (2016). Compassionate pedagogy: The ethics of care in early childhood professionalism. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 24(2), 173–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2014.970847

Tronto, J. (2013). Caring democracy: Markets, equality, and justice. New York University Press.

Uppal, S., & Savage, K. (2021). Childcare workers in Canada. Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/75-006-x/2021001/article/00005-eng.pdf?st=5BuvR8iD

Urban, M., Vandenbroeck, M., Van Laere, K., Lazzari, A., & Peeters, J. (2012). Towards competent systems in early childhood education and care: Implications for policy and practice. European Journal of Education, 47(4), 508–526. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12010

van Groll, N., & Kummen, K. (2021). Troubled pedagogies and COVID-19: Fermenting new relationships and practice in early childhood care and education. Journal of Childhood Studies, 46(3), 30–41. https://journals.uvic.ca/index.php/jcs/article/view/20047

Van Laere, K., Peeters, J., & Vandenbroeck, M. (2012). The education and care divide: The role of the early childhood workforce in 15 European countries. European Journal of Education, 47(4), 527–541. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12006

Vickerson, R., Friendly, M., Forer, B., Mohamed, S. S., & Nguyen, N. T. (2022). One year later: Follow up results from a survey on COVID-19 and childcare in Canada. Childcare Resource and Resource Unit. https://childcarecanada.org/sites/default/files/One-year-later-follow-up-Covid19-provider-survey-2022_0.pdf

World Health Organization. (2020). WHO Director - General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020

Zembylas, M. (2013). Critical pedagogy and emotion: Working through ‘troubled knowledge’ in posttraumatic contexts. Critical Studies in Education, 54(2), 176–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2012.743468

Zembylas, M. (2021). The affective dimension of everyday resistance: Implications for critical pedagogy in engaging with neoliberalism’s educational impact. Critical Studies in Education, 62(2), 211–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2019.1617180

Zembylas, M., Bozalek, V., & Shefer, T. (2014). Tronto’s notion of privileged irresponsibility and the reconceptualisation of care: Implications for critical pedagogies of emotion in higher education. Gender and Education, 26(3), 200–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2014.901718

[1] The Province of Québec is a notable exception. It used to offer $5/day care, though now it is $8.35/day (Ministère de la Famille, 2022)

[2] A “competent” system is defined as one which unfolds at different levels---within the individual, the program, between programs, and in governance---and is expressed through the dimensions of knowledge, practices, and values (Urban et al, 2012).