Asônimâkêwin: Passing on What We Know

Krissy Bouvier-Lemaigre

First Nations University of Canada

Author’s Note

Correspondence regarding this article should be addressed to Krissy Bouvier-Lemaigre at klemaigre@icsd.ca

__________

Land has traditionally been considered a sacred, healing space where anyone who is connected to a place can find what he or she needs to maintain, sustain, and build a healthy life. (Okemaw, 2021. p. 19)

This paper focuses on the Cree term asônimâkêwin,[1] passing on what we know. I have learned the concept of asônimâkêwin from teachings shared with me during a land-based language immersion camp with Dr. Angelina Weenie (personal communication, July 27, 2021). Dr. Weenie is a First Nations woman from Sweetgrass First Nation in Saskatchewan. I have had the honour of learning from her through course work at the First Nations University of Canada. She has encouraged me to record my community’s landscapes and stories.

Through asônimâkêwin, I will pass on my knowledge of the land and waterways, the Michif language and the history of my home community of Île à la Crosse, Saskatchewan. I will explore the history and present-day land use and the islands and rivers located around Île à la Crosse. I will share how storytelling and spiritual ecology have always connected the people of Île à la Crosse to these landscapes and waterways. It is my hope to share what was been passed on to me by nîtisânak, and kihtêyak, with the next generation.

Nîya

Tânsi Krissy Bouvier Lemaigre nisihkâson. Sâķitawak ohci niya. ninâpîm, Justin isihkâsô. Nitânis Kassidy êķwa nikosis Kale isihkâsôwak. Ni-miyowihtîn dahwârr ta-ayâyân. Apisîs poķo li Michif êķwa nehiywîwin ni-pîkiskwan. Nimoshômak, nohkomak, mîna nocâpânak oķimâw âsotamâķêwin mitâtaht. Maķa nocâpân Abraham oķimâw âsotamâķêwin niķotwâsik ohci kîpîtahtcihô. Nimoshômak, nohkomak, mîna nocâpânak, Nêyihawîwin, Denesuline êķwa Li’ Michif kî-pîkiskwêwak. Askî kâpimâcihowak. Na kininahawmomwahk nicawasimsak askî apâcihtatwaw.

My name is Krissy Bouvier Lemaigre. I am from Île à la Crosse. My husband’s name is Justin. My daughter is Kassidy and my son is Kale. I love to be outside. I speak a little bit of Michif and the Cree language. My grandparents and great-grandparents were a part of Treaty 10 Territory in the province of Saskatchewan, with the exception of my great-grandfather, Abraham Ratt, who came from Treaty 6 Territory. I come from a history of rich languages and land use. My great-grandparents and grandparents spoke Cree, Dene, and Michif. They respected the land and used the land to survive. Respecting and learning from the land is what has been passed down to me. This teaching I will pass down to my children.

Sâķitawak kayas

Sâķitawak is the second oldest community in Saskatchewan, Canada. As I learned from nimama Karen, Sâķitawak means “a meeting place where it opens.” The fur traders changed Sâķitawak to the name Île à la Crosse. Île à la Crosse translated to English means “Island of the Cross.”

The Beaver River, Churchill River, and Canoe River meet at Lac Île à la Crosse. The Churchill River connects Lac Île à la Crosse through a series of lakes to the Methye Portage and to Lake Athabasca. This became the trail to the Northwest Territories. Because of its prime location along the Churchill River, Sâķitawak quickly became a major hub on the fur trade route during the latter part of the 18th century and most of the 19th century (Longpré, 1977). Cree, Dene, French, and English were the languages spoken during these centuries. Many of our people were multilingual and spoke all four of these languages fluently in Sâķitawak and on the trail to the Northwest Territories. During these years, a distinct Métis community formed through familial and trading relationships between the Indigenous inhabitants and French traders. Hence, the beautiful Michif language, a mixture of the Cree and French languages, was born.

Sâķitawak anohc

Today, Île à la Crosse is a strong Métis community. English is the dominant and commonly used language in the community. Michif and Cree are still spoken in the community, but not as prevalent as in the past. School and community efforts are currently underway to keep our languages alive. At the school level, Michif language nests are a part of the prekindergarten and kindergarten programs. Michif classes are taught from Grade 1 through to high school where Michif 10 and Michif 20 classes are offered. Michif language and culture are very much a part of the school environments. At the community level, morning radio programming is done completely in the Michif language. Guest speakers from the community and surrounding areas often call in to share stories in Michif about life in the past. When the community gathers, the Michif language is included in introductions and prayers.

Our families continue to hunt and fish and gather berries and medicines to keep our traditional ways with us. The islands around our community that were once lived on throughout the years have become seasonal homes for camping and gathering. The land and waterways are still a big part of our lives. Forestry, wild rice harvesting, and commercial fishing continue to be sources of employment and livelihood for our people.

Islands and Rivers

I have learned of the islands and rivers that Île à la Crosse families lived on from nimoshom Napoleon. Many of the Métis families lived on different islands around the Île à la Crosse area: Niyâwahkâsihk (Sandy Point), Ali Baloo, La ķrrôsil (Big Island), Niyâwahkahk (South Bay), Opâsêw Sîpî (Canoe River), Asawâpêw Wâsaķâmîciķan (Fort Black) and Amisko Sîpî (Beaver River). In the past, families lived in these areas year-round. They used the land and water for hunting and fishing, and for gathering berries and medicines. They also grew big gardens in the summer, which were harvested and preserved in the fall to put away for the long winter months. As Dr. Angelina Weenie has shared, these places in our communities are significant as they become our places of knowing and being. The stories and landscapes become our identity (A. Weenie, personal communication, July 28, 2021).

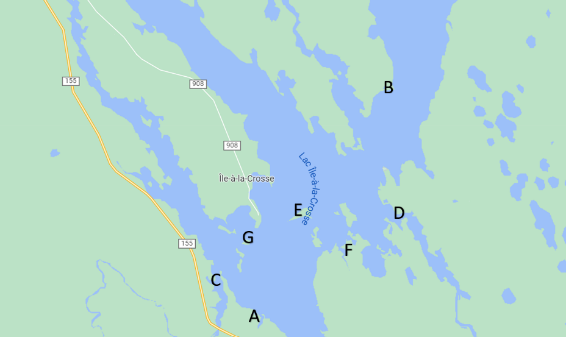

Figure 1

Map of Île à la Crosse Area

Note. Map of Île à la Crosse area. A= Niyâwahkahk; B= Niyâwahkâsihk; C= Opâsêw Sîpî; D= Amisko Sîpî; E= La ķrrôsil; F= Asawâpêw Wâsaķâmîciķan; G= Ali Baloo. Adapted from Map Data © 2022 Google (https://www.google.com/maps/@55.4328039,-107.8479807,11z).

Niyâwahkahk is the Michif name for South Bay. Niyâwahkahk anohc is a seasonal spot for families to camp in the summer months and to gather berries. Families from Île à la Crosse, Buffalo Narrows, Beauval, Canoe Lake, and Cole Bay gather during the summer for activities such as camping, swimming, picnics, weddings, berry picking, and various cultural activities and celebrations. There is always more than enough food and laughter can be heard for miles around. You can also hear the Cree, Dene, and Michif languages in many camping spots and on the blueberry and cranberry patches. Lî blowan êķwa wîsaķîmina are picked and preserved for the winter months. Cree, Dene, and Michif are spoken with the older generations. The English language is spoken with the younger generations.

Niyâwahkâsihk is the Michif name for Sandy Point. Sandy Point is a small piece of land between Île à la Crosse and Patuanak. There are still cabins at Sandy Point that belong to the Gardiner, Morin, and Misponas families. These families resided on this land year round. Today, these families camp, hunt, fish, and practice our traditional ways of life. Niyâwahkâsihk was and still is a stopping place for the people of Patuanak who travel by water.

Opâsêw Sîpî is the Michif name for Canoe River. Canoe River connects us to our neighboring community of Canoe Lake. There are many cabins alongside this river. Families use these cabins year round for camping, hunting, fishing, and learning from the land. Maskihkî is the Michif word for medicine. Two of the common medicines still picked from this river are wacask omîcôwin and wascatamô. These medicines are picked in the summer. They are dried and used for medicinal purposes throughout the year. I have learned about these medicines from nimama Karen. As a young girl, she would accompany her moshom Abraham on the canoe as he collected these medicines.

Amisko Sîpî is the Michif name for Beaver River. The Caisse, Laliberte and Desjarlais families still have cabins along this river. Beaver River connects us to our neighboring community of Beauval. Beaver River is used for fishing in the summer and winter months.

La ķrrôsil is the Michif name for Big Island. In the past, the Ratt family resided here year round. They had a home and a garden and they hunted from this piece of land. Today, there are no houses or cabins on La ķrrôsil. Families gather for swimming, boating, and picnicking in the summer months.

Asawâpêw Wâsaķâmîciķan is the Michif name for Fort Black. As learned from village council member Gerald Roy (personal communication, May 29, 2022) recently, Fort Black was the site of the first Northwest Trading Post. It was a trail that was used to haul freight to northern communities along the Churchill River system. In a documented interview in the Sâķitawak Bi-Centennial book, the late Elder Vital Morin shared that,

There used to be a wagon road from Fort Black all the way to Meadow Lake. That road was cut open. There was a government project in those days. I worked on that road myself, that was in the forties. The road was all handmade—corduroying the soft spots, the sandy spots, and then pulling some soil on top of that. There were a lot of mud holes. At that time, we worked for 50 cents a day, this was in 1940-41. (Longpré, R., 1977, p. 57)

There is more history in Fort Black that needs to further explored. The Fort Black Trail was designated a historic site in 1953 by the Government of Canada.

Ali Baloo is a tiny island near tip of the Île à la Crosse peninsula. There is no English translation for this name. Nimoshom Napoleon grew up on this island. He lived on Ali Baloo with his parents and his brothers and sisters. Nimoshom and his family had a deep connection to the land as they relied on it for survival. They had a big garden in the summer months. The potatoes they harvested were stored under the floor boards of their home. Nimoshom’s mom, Flora, preserved fruits and vegetables for the winter months. Nimoshom and his brothers fished and hunted for game. Today, there is only one house left on Ali Baloo. The plants and shrubs have grown over most signs of settlement.

The lakes, rivers, and islands are very much a part of who we are. They are just as important to us today as they were to the generations of the past. These islands and waterways tell us beautiful stories of family and connection. They also tell us stories of the hardships that nîtisanak faced during their time on Mother Earth.

Storytelling as a Way of Preserving the Legends of Our Lands

Families that lived in Île à la Crosse and the surrounding areas told stories and legends as a way to pass down our histories. Bone et al. (2012) described the importance of oral stories in the following:

We are an oral people. We cannot transfer our way of life through written words alone. Sacred law must be spoken and heard. Our way of life is meant to be lived and experienced. Our words are meant to inspire and guide our fellow human beings to follow the path of the heart. (n.p.)

Today, our stories seem to be safely tucked away. It takes trust and relationships to find and hear these stories. There is a story as told by mônôk Isadore. It is about La ķrrôsil and how Île à la Crosse came to be named:

Amiskowîsti ohci kâ-kî-mâcipayit, nîso amiskwak î-kî-wîkitwâw Amiskowîsti. Ekotohci a la ķrrôsil kâ-kî-mâcipayik. Piyak kîsikaw amiskwak kî-sipwîcimîwak î-kî-pâm-natonâtocik. Amiskwak namwâc ohci pîķîwîwak. Amiskowîsti kî-pahkihtin ekotohci mîtawîwin eķota mîtawîwak môniyâwak la crosse isihkâtamwak eķwânima mîtawîwin. Eķotohci Île à la Crosse owîhôwin kâ-kî-mâcipayik.

Big Island was once a beaver lodge to two beavers. One day the beavers swam away, looking for each other. The beavers never returned and the lodge eventually collapsed and became a lacrosse field. This is how Île à la Crosse came to be named. (I. Campbell, personal communication, July 25, 2021)

Our stories are important. They are who we are; they are a connection to the land and to our ancestors. Our stories, from our voices, must be passed on to the next generation through oral storytelling and they must recorded from kihtêyak, our old people. This is how our histories and who we are as a people stay with us and with the next generation.

Stories were also told by kihtêyak to teach lessons. There is a local story about a giant sturgeon fish in our lake. Nâmêw is the Michif word for sturgeon. The name of nâmêw is Puff. It is told that Puff lives below La ķrrôsil. There are three rivers that all meet around La ķrrôsil and the currents are quite strong. Children were warned not to swim past the drop off at the beach or Puff would come, grab you, and take you away. It is believed that this story was told to keep children from swimming too far out on the lake, to prevent possible drownings. Stories were told to pass down histories, to teach lessons and to keep our people safe and away from harm.

Spiritual Ecology

Spirituality is an inner connection to everything around one: the land, the water, the animals, the stars, the sky, and the spirit world. Spirituality is a connection to our past, our present, and our future. I am most at peace when I am surrounded by trees and water. I feel that is where healing takes place for me. I am blessed to live alongside the Churchill River. I watch her throughout all six seasons: spring, break-up, summer, fall, freeze-up and winter. She is beautiful and magnificent. She provides life every day. The trees that surround me are my protectors. They give me a sense of security and peace. They, too, are life givers. They give us new breath. The most precious gifts that I have received are rocks from Mother Earth. They are calming for me. I feel grounded when I have a rock in my hand. When my children or my students give me rocks, I feel it is a blessing and a reminder for calmness and peace.

There has always been a spiritual connection between Indigenous people and the land. Nimama shared a story about her moshom Abraham and picking medicine from the water.

My moshom Abraham would take me on the canoe when he went picking medicine. It was beautiful. I would sit in the front and he would paddle. It was quiet and peaceful. He spoke to me in Cree. I felt very connected to my moshom and the land. (K. Bouvier, personal communication, May 15, 2021)

There is so much to learn from this short story and the spiritual connection to the land. Nimama felt most at peace when picking medicines with her moshom. Moshom Abraham knew the waterways and thanked the Creator for this knowledge and the medicine. He shared this experience with his granddaughter. This memory will forever be etched in her being. It is not only a spiritual connection to the land, but a spiritual connection to her moshom as well.

I had the honour of attending a land-based learning opportunity on spirituality. Knowledge Keeper Kelsey Bighetty from Pukatawagan in Northern Manitoba was our guide through this learning. I learned of connections to the land and land as a living being. Mr. Bighetty spoke of his battles and feeling alone in this world and how it was the land that saved him.

I was feeling alone so I started to pray to the Creator. All of a sudden, two blades of grass started talking…then the trees started talking…the rocks started talking. All things of the earth are alive. Everything has a purpose in life. (K. Bighetty, personal communication, July 28, 2021)

This personal story of healing and connection to the land is spiritual. With the help and support from the land, Mr. Bighetty was able to make changes to live a healthier life.

It is challenging to capture and write the essence of spiritual ecology, it is something that we feel in our soul.

Language and the Land

As Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island, the land has been and continues to be our teacher. Land-based learning, as defined by Okemaw (2021) includes, “prior knowledge known by Indigenous people about the plants, medicines, and animals of the land and respecting the sacredness of the land and particular places (p. 90).” This definition fits right in with asônimâkêwin. We pass on what has been given to us by nîtisânak and kihtêyak.

In my home community, the young and the old are relearning the teachings from the land and kihtêyak. Culture camps are one way that school and community groups are bringing back land-based learning and language learning. Both the elementary and high schools organize seasonal culture camps for students. These camps teach students about, survival, ecology, hunting and fishing, and medicines. The schools bring in local Elders and Knowledge Keepers to teach students this way of life. When our students are in this setting, they are so at ease and much learning happens. Some of the goals of culture camps are to reconnect our students to the land. Teachings of keeping the land clean, taking only what is needed and offerings of tobacco to thank her for her gifts are the bigger goals of these camps. It is vital that our students understand these teachings.

Community groups such as the Île à la Crosse Friendship Center have offered healing camps on the land for both men and women. Again, local Elders and Knowledge Keepers are brought in to teach and listen. These camps address the negative impacts of oppression, colonialism and racism. It helps our men and women reconnect to the land and find healthy paths to healing.

I had the privilege of attending a woman’s healing retreat in the winter of 2022. This retreat was held outside the community, at a cabin in the bush. At this retreat, I participated in a grief healing circle with Elder Marie Favel. This was a very powerful experience for myself and the other women present. It was healing. At this camp, I was honoured to share my gift of beading alongside two fellow beaders, Erin and Chellsea. Meals and tea were shared throughout the day. As a group of women, we healed through voice, beading, and food. This is one example of the type of camps that the Île à la Crosse Friendship Center offers community members.

As Dr. Weenie (2020) discussed, land represents a relationship between people and place. Indigenous people are all about place. We are all on different journeys of healing and reconnecting. We are finding our ways back to the land: to connect, to heal and to belong.

Conclusion

Learning about the history of our landscapes and waterways, stories and legends, spiritual ecology, and our languages is crucial for our identity. Passing on these stories to our children and the next generation is equally as important. Asônimâkêwin comes in many shapes and forms. The knowledges that have been passed on to me through oral storytelling and research have been written in this paper. Learning these stories and histories shapes our identity as Indigenous peoples. It shows our deep connection to the land and waterways. This knowledge needs to be passed down from generation to generation, to maintain our Indigenous identities.

References

Bone, H., Copenace, S., Courchene, D., Easter, W., Green, R., & Skywater, H. (2012). The journey of the spirit of the red man: A message from the Elders. Trafford.

Okemow, V. N. (2021). Learning and teaching an ancestral language: Stories from Manitoba teachers. J. Charleton Pub.

Longpré, R. (1977, January). Ile-a-la-Crosse 1776-1976. Sakitawak Bicentennial. https://www.jkcc.com/sakitawak.html

Weenie, A. (2020). Askiy kiskinwahamâkêwina: Reclaiming land-based pedagogies in the academy. In S. Cote-Meek &T. Moeke-Pickering (Eds.), Decolonizing and Indigenizing education in Canada (pp.1–17). Canadian Scholars Press.

[1] See Appendix I for a Glossary of Northern Michif Dialect

__________

Appendix I

Glossary: Northern Michif Dialect

anohc: today

asônimâkêwin: passing on what we know

kayas: a long time ago

kihtêyak: Elders

lî blowan êķwa wîsaķîmina : blueberries and cranberries

moshom – grandfather

nâmêw: sturgeon fish

nimama: my mom

nimoshom – my grandfather

nîtisânak: my family

Niyâwahkahk: South Bay

Niyâwahkâsihk: Sandy Point

Opâsêw Sîpî: Canoe River

Sâķitawak: a meeting place where it opens

wacask omîcôwin: rat root

wascatamô: roots of the lily pad