Investigating

the Reading Strategies Used by French Immersion Pupils as They Engage

With Dual-Language Children’s Books: A Multiple Case Study

Joël

Thibeault1 and Ian A. Matheson2

1University

of Ottawa

2Queen’s

University

Reading

is a fundamental component of education systems. Through reading

instruction, students not only acquire the skills and attitudes to

make meaning out of text, they also develop the capacity to construct

knowledge related to literacy and other disciplines. In French

immersion programming, pupils simultaneously learn how to read in

both French and English, and the abilities they develop transfer from

one language to the other. As this program is becoming increasingly

popular throughout Canada, scholars have started to zero in on the

acquisition of reading skills by French immersion students, and have

looked to identify teaching methods and approaches that reflect their

characteristics. In this perspective, for this paper, we aim to

explore French immersion students’ use of reading strategies

while they read a type of text that is gaining traction in language

and literacy education research: dual-language books.

Theoretical

Framework and Literature Review

Research

on reading acquisition has notably highlighted that dynamic

thinking—active and conscious decision-making on how to

effectively build meaning from a particular text—is a quality

of good reading (Matheson & MacCormack, 2021; Paris & Jacobs,

1984). It should, therefore, come as no surprise that such dynamic

thinking is recognized as being effective in both monolingual and

bilingual reading contexts. In fact, readers who actively use their

first language (L1) as a tool for making sense of text in their

second language (L2) usually gain more success in reading (Cisco &

Padrón, 2012; Jiménez et al., 1996). In other words,

readers who acknowledge that cognitive transfers between L1 and L2

provide them with powerful opportunities to make meaning out of text

can rely on a wider variety of skills and knowledge to do so.

Whereas research in immersion is

starting to recognize that we should teach for transfer (Cummins,

2008), there seems to be a culture of monolingualism that prevails in

French immersion contexts (Cormier, 2018). To make sure that students

can benefit from the program, teachers seem to emphasize and

prioritize a complete exposure to the students’ second

language. If a predominately francophone environment remains one of

the underlying traits of French immersion classrooms, Swain and

Lapkin (2013) contend that teachers can draw upon their students’

knowledge of English to enhance their linguistic repertoire and teach

them how to strategically use it when they are learning French.

Ballinger (2013), through the implementation of a biliteracy project

in French immersion, further noted that students who took part in

this biliteracy initiative were able to reciprocally employ

strategies that could be used in both English and French as they were

completing different language tasks.

This body of literature encouraged us

to consider the resources that teachers can utilize in order to

support students as they transfer their knowledge and skills from one

language to the other in French immersion contexts. One promising

approach for L2 learning using the learner’s L1 is through the

use of dual-language children’s books. These books, which

contain different languages, can therefore allow for active and

conscious decision making about how to use one language for reading

and learning in the other (Armand et al., 2016; Simoncini et al.,

2019). While some research has begun to examine how readers engage

with dual-language texts (e.g., Sneddon, 2009), Thibeault and

Matheson (2020) identified a paucity of studies focused more

specifically on French immersion.

Second

Language Reading

Reading comprehension is built through

the use of goal-oriented cognitive or physical actions focused on

decoding text and constructing meaning—these actions, which

represent a fundamental part of the dynamic thinking mentioned in the

previous section, are known as reading strategies (Aydinbek, 2021;

Turcotte et al., 2015). Research on reading strategies notably

distinguishes between effective and ineffective reading behaviours;

good readers would use reading strategies both more often and more

effectively than poor readers (Anastasiou & Griva, 2009; Lau,

2006). It is noteworthy, moreover, that effective readers make

adjustments to their application of strategies in response to the

demands of the text (Mokhtari & Sheorey, 2002). This information

also reflects the findings of researchers who focused on second

language readers. These scholars, moreover, have highlighted the role

of the languages known by the reader as they engage in a second

language reading task. Effective bilingual readers would therefore

shift among their L1 and L2, translating from one language to the

other, and using specific features of the L2 text to signal specific

strategy use, such as drawing on cognate vocabulary (Alsheikh, 2011;

Jiménez et al., 1996).

In

the specific context of French immersion, Bourgoin (2015) found that

elementary-aged French immersion students that were effective readers

transferred strategies across their L1 and L2. In other words,

students who understand that certain strategies (e.g., predicting,

rereading) can be used in both French and English would tend to be

more effective readers. Frid (2018) further showed that French

immersion readers deployed different types of strategies when they

read an English or a French text. In French, they more frequently

recruit text-based strategies such as necessary inferencing and

summarizing. On the other hand, strategies such as predicting and

references to background knowledge, which may enable the student to

consolidate the text to memory, were utilized more often in English.

Research focusing on the reading

strategies deployed by French immersion learners thus shows that

efficient readers transfer strategies from one language to the other

as they engage in a reading task and that the same reader may use a

different set of strategies depending on the language in which the

text is written. In light of this, we can wonder whether the use of

dual-language books can allow the reader to use their entire

repertoire of strategies as they read the text and, more broadly,

whether the presence of two languages in the book can provide

opportunities for them to easily make cross-linguistic connections

when they read.

Dual-Language

Books

Dual-language books are text in which

two languages cohabit to a certain degree, and both languages are

intended to be read simultaneously by the reader. Perregaux (2009),

alongside Ernst-Slavit and Mulhern (2003), also distinguished between

different types of dual-language texts. One type, which we refer to

as a “translated text,” includes equal representation of

both languages throughout the entire text. Alternatively, a type we

refer to as “integrated texts” contains both languages,

though not as equivalent passages. These passages may work together

to forward the text narrative in an embedded and organic way, such as

with two characters that speak different languages.

Dual-language books are increasingly

being examined by researchers due to their potential for leveraging

skills in one language in order to scaffold learning and reading in

the other (Simoncini et al., 2019; Taylor et

al., 2008). Scholars have praised these texts for their

potential for legitimizing cultural and linguistic diversity, and

constructing a sense of community (Fleuret & Sabatier, 2019;

Moore & Sabatier, 2014), let alone the literacy benefits related

to vocabulary development (Gosselin-Lavoie, 2016; Read et al., 2021),

metalinguistic awareness (Robertson, 2006; Thibeault &

Quevillon-Lacasse, 2019), and graphophemic knowledge (Naqvi et al.,

2012).

Sneddon (2009) appears to have been

one of the first authors to examine reading strategy use specifically

with dual-language texts; according to her findings, the strategies

that helped readers the most with constructing meaning varied

according to their language background and competence with the

languages at play, as well as how closely related the languages in

the book were on a linguistic level. More recently, Domke (2019)

described the reading strategies that Grade 3 and Grade 5 bilingual

Spanish-English students schooled in the United States used as they

read a translated text. She focused on the strategies used to

translate words and retell passages. Results show that younger

students used strategies which tended to focus on text features

(e.g., position of words on the page), while older students more

frequently used strategies that are connected to the languages they

knew (e.g., grammatical inference).

In our previous research (Thibeault &

Matheson, 2020), we also documented the cross-linguistic strategy use

of elementary-aged French immersion students as they read

dual-language texts. Cross-linguistic strategies are behaviours that

rely on the interaction of the languages found in the book, unlike

their monolingual counterparts, which rely exclusively on one

language. We identified that readers collectively

used equivalent passages in one language to assist with passages in

the other, used potential cognates to indicate what a particular word

might mean, and used context within one language to assist with

meaning construction in another language. Some readers also

identified structural features of the dual-language text in order to

determine how they should read it; these students determined whether

or not French and English passages were direct translations of each

other, or altogether separate passages that worked together to

tell the story. We further discovered that the use of these

cross-linguistic strategies varied for some participants according to

what type of dual-language text they were reading. Some of our

participants did not adjust their reading strategies when reading the

integrated text—they would, for example, look for a direct

translation and, as a result, experience comprehension gaps as they

read.

Despite the identified value of using

dual-language texts as educational tools, there is still much to

learn about how bilingual children engage with dual-language books.

While we are beginning to understand the repertoire of strategies

that students use while reading (Domke, 2019; Sneddon, 2009), and

with particular types of text (Thibeault & Matheson, 2020), we

need to further examine how these strategies are being used with

dual-language children’s books, specifically in French

immersion contexts. In this paper, we therefore

aim to build on our previous work, which focused exclusively on

cross-linguistic strategies, to examine how elementary-aged French

immersion students use reading strategies—both monolingual and

cross-linguistic. To do so, we will also focus on two types of

dual-language books: translated and integrated. More

specifically, we wish to answer the following two questions:

What

are the reading strategies that elementary students in French

immersion use while reading different types of dual-language

French/English children’s books (i.e., translated and

integrated texts)?

How

do these students use reading strategies when they engage with each

type of dual-language children’s book (i.e., translated and

integrated texts)?

Methodology

In

order to thoroughly describe the strategies that elementary students

used when they read two types of dual-language books, we opted for an

exploratory and descriptive multiple case study approach (Duff,

2008). The initial study was composed of 16 Grade 3 and 4 students

who were schooled in a Saskatchewan city centre in two different

split classrooms. These classrooms were located in two schools within

relatively affluent neighborhoods. Students predominantly spoke

English with their parents and siblings, but some of them declared

French and Urdu as languages used at home.

From the larger sample, we identified

three students in Grade 3—Kaya, Maria, and Karly—as rich

cases. As part of a larger study focused on understanding the

strategies, thoughts, and behaviours of

elementary-aged French Immersion students as they read dual-language

children’s books (Thibeault & Matheson, 2020), these cases

were selected because the students, through data collection, provided

clear insight into their varied strategy use and reading behaviours,

as well as their intentions. As can be seen in the results section,

these three participants also obtained different scores at the

comprehension tests they had to complete after reading the integrated

and translated dual-language book.

Figure 1

Cover

of Enchantée!/Pleased to meet you! (Brunelle &

Tondino, 2017)

Data

collection took place during class time; participants were met

individually by a member of the research team in a meeting room near

their classroom. They were asked to read passages of two books for

this study: one translated dual-language book, the other integrated.

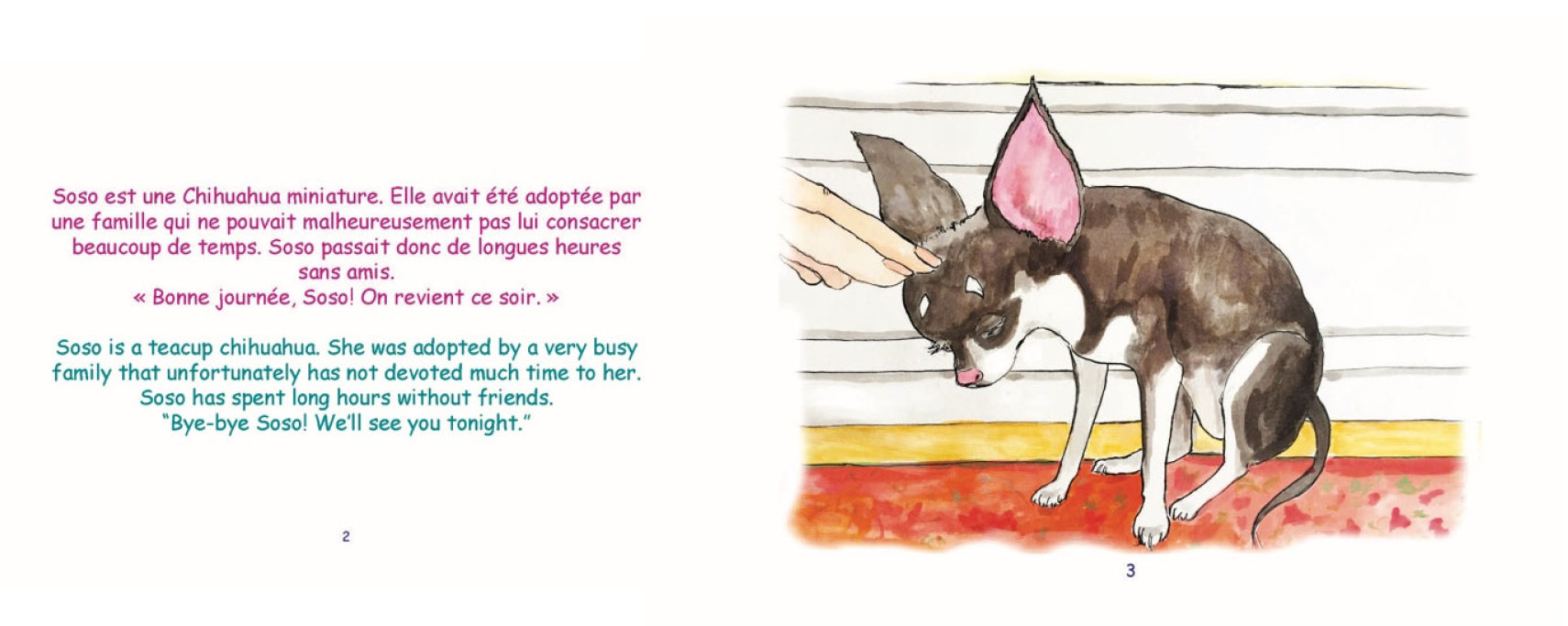

The translated text style used in this research is characterized by

parallel French and English text; the story is told in both languages

word for word, and our participants read this text first. We chose a

book entitled Enchantée! Pleased to Meet You!

(Brunelle & Tondino, 2017; see

Figures 1 and 2), because it was the appropriate reading level

for the participants. In this particular book, the French text

appears in pink on the left side of the page above the same text in

English, and an image always appears on the right page. The story

depicted the relationship of a pet Chihuahua named Soso and a mouse

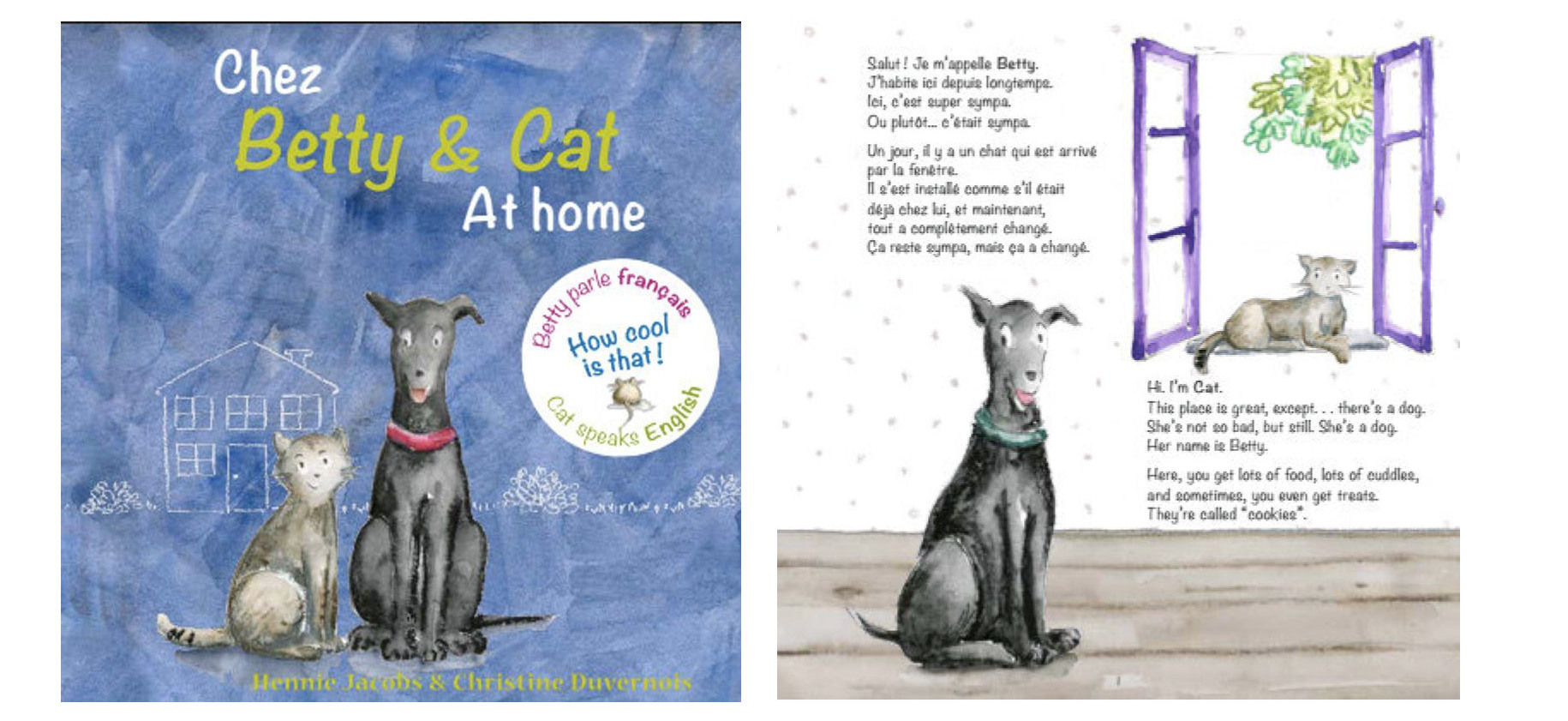

named Frieda. Contrastingly, the integrated text style is

characterized by non-equivalent French and English text; each

language is used to tell a different part of the story, and our

participants read this text second. Our participants read Chez

Betty & Cat at Home (Jacobs

& Duvernois, 2016; see Figure 3), again selected for its

age-appropriateness. Both the French text and the English text appear

on the same page again, and images accompany each page of text.

The story focuses on the coexistence of an English-speaking cat named

Cat and a French-speaking dog named Betty, who each tell the same

story using their own unique perspective of the events.

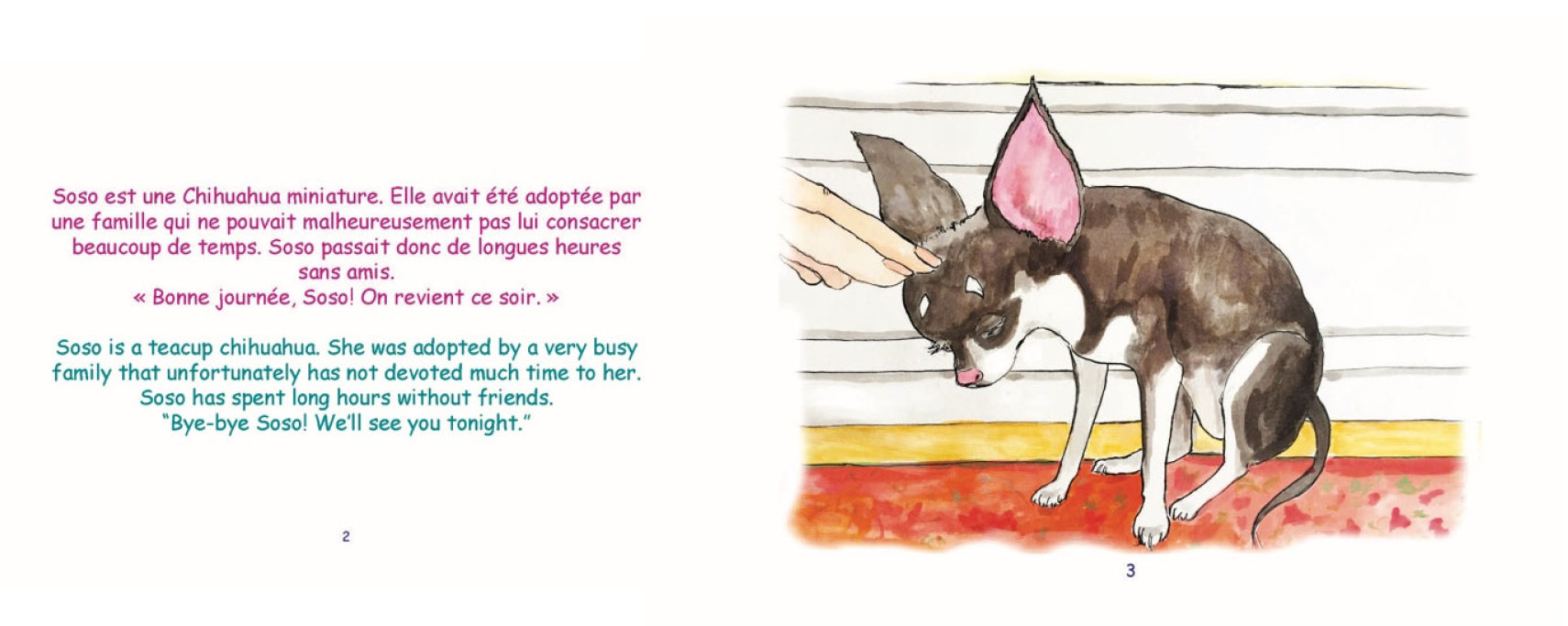

Figure 2

Passage

of Enchantée!/Pleased to meet you! (Brunelle &

Tondino, 2017)

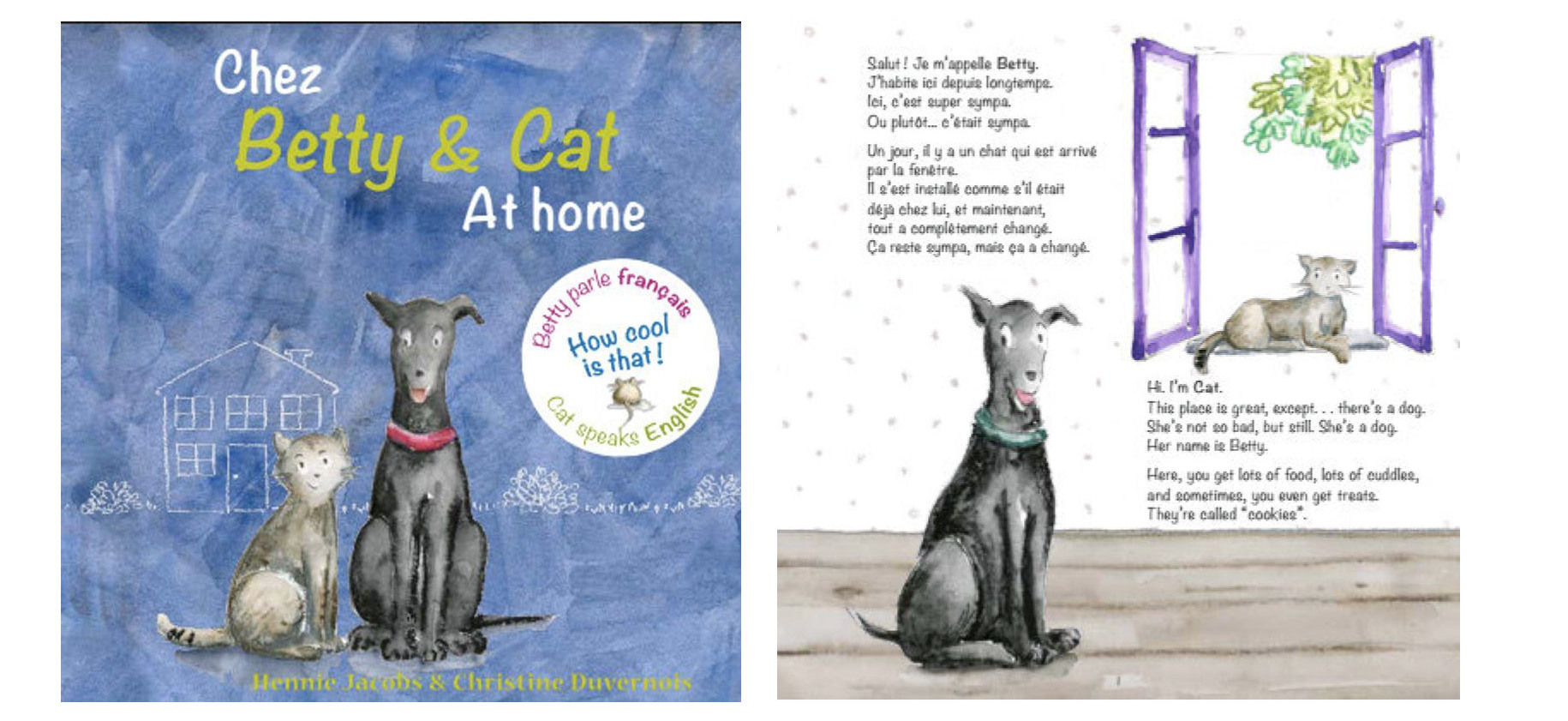

Figure

3

Cover

and passage of Chez Betty & Cat at home (Jacobs &

Duvernois, 2016)

In

each case, participants read aloud from parts of both books. We

selected the first eight pages of each text in order for participants

to provide us with an example of their reading of each text type, and

to allow them to begin to follow the emerging story. After every

page, we asked each participant to share with us what they had done

to make sense of the text, and provided a clarifying prompt where

needed to understand what students had done if there were parts of

the text that they did not understand. Following each text, we asked

readers to complete a set of multiple-choice questions. Each set

included a mix of two types of questions; one type could be answered

by identifying direct information within the text, while the other

type required readers to make inferences about information within the

text. The integrated text was followed by seven questions, and the

translated text was followed by eight. Lastly, after they completed

the comprehension questions for each text, we asked in a

retrospective portion of the interview to provide general comments

about what they had done to make sense of each text through general

questions about the books as a whole, rather than specific passages

within them.

We audio-recorded each session

(read-aloud and retrospective interview) in order to produce verbatim

transcriptions as data sources for our analysis. In order to identify

reading strategies, we used a moderate

inductive approach (Anadón & Savoie-Zajc, 2009). Our

analysis thus relied on both a classification

of reading strategies used with monolingual text (Jiménez

et al., 1996), and a set of cross-linguistic

reading strategies that emerged from our previous work on

dual-language books (Thibeault & Matheson, 2020). We also allowed

for the emergence of codes and themes from the data as we were

coding.

For each of the three cases selected

for this study, we began our deductive analysis by first noting every

instance where the participants used a reading strategy according to

our classifications (Jiménez et

al., 1996; Thibeault & Matheson, 2020).

Next, we engaged in our inductive analysis by noting every

instance where participants had provided a strategy that had yet to

be incorporated in our typology. We used this approach in this order

across both the read aloud sessions and retrospective interviews, for

all three cases. After agreeing on our approach to coding the data,

the two researchers independently recoded each of the transcripts

across the three cases, which resulted in a 91% interrater agreement,

with any disagreements being resolved through discussion. The

complete list of reading strategies, as well as definitions, can be

seen in Table 1.

Table

1

Definitions

of Reading Strategies

|

Reading

Strategy

|

Definition

|

|

Monolingual

Strategies

|

|

Focusing

on vocabulary – French

|

Referring

to specific French words in the text

|

|

Focusing

on vocabulary – English

|

Referring

to specific English words in the text

|

|

Decoding

– French

|

Applying

knowledge of letter-sound relationships to read French words

|

|

Decoding

– English

|

Applying

knowledge of letter-sound relationships to read English words

|

|

Demonstrating

awareness

|

Recognizing

instances of comprehension or miscomprehension

|

|

Invoking

prior knowledge

|

Referring

to knowledge constructed prior to reading the text

|

|

Affective

response

|

Providing

an affective response to the text

|

|

Making

inferences

|

Drawing

a conclusion based on textual evidence and reasoning

|

|

Using

context (within same language)

|

Using

a passage from the text to understand another passage written in

the same language

|

|

Re-reading

|

Reading

a passage an additional time in order to better understand it

|

|

Asking

questions

|

Interrogating

oneself or the interviewer about an element in the text

|

|

Use

of pictures

|

Referring

to pictures to make meaning of the text

|

|

Predicting/confirming

|

Constructing

meaning from the text by making informed predictions and verifying

their accuracy

|

|

Skipping

words or passages – French

|

Moving

ahead in the text in order to avoid a specific French word or

words

|

|

Skipping

words or passages – English

|

Moving

ahead in the text in order to avoid a specific English word or

words

|

|

Cross-Linguistic

Strategies

|

|

Using

passages in other language

|

Using

passages in one language to make meaning of passages written in

the other

|

|

Using

cognates

|

Using

cognates that are not found in the text to make meaning of an

unknown word

|

|

Using

context (cross-linguistically)

|

Using

contextual clues found in the other language to make meaning of

passages in one language

|

|

Using

structure

|

Relying

on the structural features of the dual-language text to understand

how languages interact in the text

|

|

Paraphrasing

through translation

|

Translating

passages from the text in the other language

|

Results

To

present the results, we will showcase the strategies that each of our

three focal readers deployed as they read dual-language books. To do

so, we will first provide the number of times each strategy was used.

This quantitative presentation of strategies, for each student, will

be followed with the presentation of different verbatim excerpts,

which we deem pertinent and representative of the strategies most

deployed by each reader.

Kaya’s

Profile

Our first focal reader, Kaya, was 8

years old and in Grade 3 at the time of data collection. She

predominantly speaks English at home, though she practices her French

from time to time when she speaks with her mother. She has been

enrolled in French immersion since Kindergarten. Following readings,

Kaya scored 6/8 on the translated text comprehension questions, and

2/7 on the integrated text comprehension questions, for a total of

8/15. In Table 2, we have inserted the reading strategies that Kaya

deployed as she read both the translated and integrated texts.

Table

2

Kaya’s

Reading Strategies

|

Monolingual

Strategies

|

TT

|

IT

|

Cross-Linguistic

Strategies

|

TT

|

IT

|

|

Focusing on

vocabulary – French

|

6

|

3

|

Using

passages in other language

|

4

|

2

|

|

Focusing on

vocabulary – English

|

3

|

-

|

Using

cognates

|

1

|

-

|

|

Decoding –

French

|

2

|

1

|

Using context

(cross-linguistically)

|

-

|

-

|

|

Decoding –

English

|

2

|

1

|

Using

structure

|

-

|

-

|

|

Demonstrating

awareness

|

12

|

7

|

Paraphrasing

through translation

|

-

|

-

|

|

Invoking

prior knowledge

|

-

|

1

|

|

|

Affective

response

|

-

|

1

|

|

|

Making

inferences

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

Using context

(within same language)

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

Re-reading

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

Asking

questions

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

Use of

pictures

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

Predicting/confirming

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

Skipping

words or passages – French

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

Skipping

words or passages – English

|

-

|

-

|

|

Note. (-) indicates strategy

was never used by the participant. TT = translated text. IT =

integrated text.

For

the translated text, we identified seven different strategies that

Kaya used. Demonstrating awareness was the most commonly used

strategy; throughout her interview regarding the translated text,

Kaya reported about her awareness of her gaps in comprehension (e.g.,

“I don’t know what these two words mean”) and where

she understood the words she read (e.g., “I didn’t have

any problems with any words”). As she engaged with the book,

she thus seemed to frequently focus on vocabulary, whether in

French or in English. The following excerpt is a relevant example of

her focus on vocabulary.

Excerpt 1

-

|

Kaya

|

I’m

not sure what this one means.

|

|

Researcher

|

Okay.

Which one? Can you read it?

|

|

Kaya

|

“Craintive.”

|

|

Researcher

|

Okay.

Is there anything that helped you?

|

|

Kaya

|

I

think it might be the same thing as this.

|

|

Researcher

|

Okay,

which is?

|

|

Kaya

|

“Alarmed”

|

|

(…)

|

|

Researcher

|

What

makes you think they are the same ones?

|

|

Kaya

|

Because

they are both the start of the sentence.

|

In

this dialogue, three codes were used. As we can see, Kaya first

demonstrates awareness when she states that she does not

understand the word “craintive.” By so doing, she

focuses on French vocabulary and, to understand the unknown

word, she relies on the equivalent English passage. She

further noticed that “craintive” and “alarmed”

were both positioned at the beginning of sentences; she was therefore

able to match the words according to their position in the sentence.

As

far as the integrated text is concerned, we also identified seven

different strategies that Kaya used. Again, the demonstration of

awareness is the most notable one; Kaya often mentioned which

words she did or not did understand (e.g., “I understand

everything and I didn’t know what was ‘sympa’”).

She once invoked prior knowledge (“It doesn’t

really sound like a word and I just thought it was a name after I

read it”) and manifested an affective response (“I

really like the drawings”). Overall, the strategies she

deployed seem quite similar for the integrated text and the

translated text. The following excerpt is taken from the interview

conducted after she read the integrated text; just as she did for the

translated text, she mentions the use of equivalent passages in one

language to make meaning of unknown words in the other.

Excerpt 2

“It’s the words and when I

didn’t understand the English or the French ones I just looked

at the English and when I didn’t understand the English and

compare it, and then if I didn’t understand a French then I

just looked at the English.”

Maria’s

Profile

Our

second focal reader, Maria, was an 8-year-old, Grade 3 student when

she took part in our study. She predominantly speaks English at home,

though she mentioned that she sporadically practices her French with

her parents. Since kindergarten, she has been schooled in French

immersion, in Saskatchewan. Maria scored 7/8 on the translated text

comprehension questions, and 6/7 on the integrated text comprehension

questions, for a total score of 13/15. Table 3 highlights the

strategies that she mentioned using as she was reading both the

translated and integrated texts.

Table

3

Maria’s

Reading Strategies

|

Monolingual

Strategies

|

TT

|

IT

|

Cross-Linguistic

Strategies

|

TT

|

IT

|

|

Focusing

on vocabulary – French

|

2

|

-

|

Using

passages in other language

|

2

|

-

|

|

Focusing

on vocabulary – English

|

2

|

-

|

Using

cognates

|

-

|

-

|

|

Decoding

– French

|

-

|

6

|

Using

context (cross-linguistically)

|

-

|

-

|

|

Decoding

– English

|

1

|

-

|

Using

structure

|

-

|

1

|

|

Demonstrating

awareness

|

3

|

3

|

Paraphrasing

through translation

|

-

|

-

|

|

Invoking

prior knowledge

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

Affective

response

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

Making

inferences

|

1

|

1

|

|

|

Using

context (within same language)

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

Re-reading

|

2

|

-

|

|

|

Asking

questions

|

2

|

1

|

|

|

Use

of pictures

|

3

|

7

|

|

|

Predicting/confirming

|

-

|

1

|

|

|

Skipping

words or passages – French

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

Skipping

words or passages – English

|

5

|

1

|

|

Note.

(-) indicates strategy was never used by the participant. TT =

translated text. IT = integrated text.

In

her reading of the translated text, we identified 10 different

strategies that Maria used. Her most recurrently used strategy was

skipping words or passages in English. This was somewhat

surprising considering that English was her dominant language and

that she never used the equivalent strategy for words or passages in

French. In fact, at the beginning of the reading session, she faced

difficulties as she was reading the English noun chihuahua,

and relied on the strategy asking questions to pose the

researcher “Can I skip it?” After the interviewer told

her to “do what you would do if you were reading on your own,”

she skipped the word. She went on using the strategy four more times,

always with English words, and mentioned that she was doing so

because some of these words were “very long.”

Though

Maria only seemed to use passages in the other language twice

when she read the translated text, she explicitly talked about this

particular strategy in the post-interview.

Excerpt 1

|

Researcher

|

Is there anything else you did to

make you understand better?

|

|

(…)

|

|

Maria

|

Using the English words to

translate in French or the opposite of that.

|

|

Researcher

|

So you did both of this?

|

|

Maria

|

Yeah.

|

|

Researcher

|

How did the English help you with

the French?

|

|

Maria

|

Eum…If I knew the English

word…If I knew the English word in English but not in

French it will help me.

|

|

Researcher

|

And how did the French help you

with the English?

|

|

Maria

|

Eum…If I knew what it was in

French but not in English.

|

Interestingly

enough, in this excerpt, she mentions that she uses both English and

French vocabulary to make meaning of unknown words in the other

language. As such, on the one hand, she skipped a few words when she

read passages in English and, on the other, she mentions that both

French and English can be used to understand passages of the book.

Though we cannot conclude that she uses her knowledge of the French

words to specifically understand the English words that she skipped,

we can nonetheless contend that Maria comprehends the scaffolding

potential of English and French passages in the translated text.

This, at the very least, provides her with a cognitive tool that she

can utilize when she skips an unknown English word.

We

identified eight distinct reading strategies that Maria used for the

integrated text. This time, the most predominant strategy was the use

of pictures, followed with decoding French words. In fact,

throughout the reading session of the integrated text, these two

strategies seemed to be consistently employed by Maria, who often

relied on one of them or both concurrently. She furthermore deployed

a low number of cross-linguistic strategies; she only noticed the

integrated structure once when she said “The cat is

English, but the dog is French.” In the post-interview, she

developed her thoughts in regard to this particular textual

structure.

Excerpt 2

|

Researcher

|

Did

the presence of two languages in this book help you understand

what you were reading?

|

|

Maria

|

Eum…

No, not really because it’s two different sentences […].

Like this one is like different. It’s like one of them is

the dog and one of them is the cat. And so, they will be different

on the same sentences in English and French.

|

|

Researcher

|

And

so that, you don’t think that the English could help you

with the French, and vise versa?

|

|

Maria

|

With

this one, no. Not really.

|

|

Researcher

|

Okay.

|

|

Maria

|

But

kind of because they are both talking about the same things but

not in like the… not the… it not written the same

way. But they’re both talking about the same things but not

exactly.

|

This

excerpt is particularly interesting because it showcases Maria’s

conflicting views regarding the integrated book’s structure and

its potential for supporting her reading comprehension. On the one

hand, she is aware that English and French passages are not entirely

equivalent in the book. On the other, she also knows that both

protagonists are narrating the same events and that the cat’s

perspectives are in fact complementary to the dog’s

perspectives.

Karly’s

Profile

Our

last focal reader, Karly, was also eight years old and in grade 3 at

the time of data collection. Like Kaya and Maria, she has been

enrolled in French immersion since kindergarten. She exclusively

speaks English at home. Karly scored 7/8 on the translated text

comprehension questions, and 7/7 on the integrated text comprehension

questions, for a total score of 14/15. In Table 4, we have inserted

the reading strategies that Karly used as she read both the

translated and integrated texts.

Table

4

Karly’s

Reading Strategies

|

Monolingual

Strategies

|

TT

|

IT

|

Cross-Linguistic

Strategies

|

TT

|

IT

|

|

Focusing

on vocabulary – French

|

4

|

5

|

Using

passages in other language

|

1

|

-

|

|

Focusing

on vocabulary – English

|

1

|

2

|

Using

cognates

|

-

|

2

|

|

Decoding

– French

|

-

|

6

|

Using

context (cross-linguistically)

|

-

|

1

|

|

Decoding

– English

|

1

|

-

|

Using

structure

|

-

|

2

|

|

Demonstrating

awareness

|

9

|

8

|

Paraphrasing

through translation

|

6

|

2

|

|

Invoking

prior knowledge

|

-

|

2

|

|

|

Affective

response

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

Making

inferences

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

Using

context (within same language)

|

2

|

1

|

|

|

Re-reading

|

2

|

-

|

|

|

Asking

questions

|

-

|

2

|

|

|

Use

of pictures

|

3

|

2

|

|

|

Predicting/confirming

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

Skipping

words or passages – French

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

Skipping

words or passages – English

|

-

|

-

|

|

Note.

(-) indicates strategy was never used by the participant. TT =

translated text. IT = integrated text.

For the translated text, we identified

nine different strategies that Karly used. Similar to Maria,

demonstrating awareness was the most often reported strategy,

and Karly used it to communicate that she did not understand

particular words in French, though she also identified a word in

English that was unfamiliar. She explicitly shared that she is better

in English than French because it was her “first language.”

Concerted efforts to make sense of the French text were evident

through phrases including “Okay it makes more sense”—something

she uttered after she read the English passage that followed an

unclear French passage. Karly also regularly paraphrased through

translation while reading the translated text—a strategy

that seemed to characterize her approach to reading the translated

text. The following excerpt is a relevant example of her regular

attempts to understand the story by paraphrasing the French text

through translation:

Excerpt 1

“La petite

souris salua Soso et s’approcha. So

like it says ‘hi’ or euh… The little mouse waved

and came toward the house. Oh okay, so kind of ‘hi.’”

In

this passage, Karly uses two different strategies—paraphrasing

through translation and demonstrating awareness. Following

the French passage, Karly attempts to translate it, suggesting that

she is trying to understand it before “checking” with the

English passage. Her use of “or euh…” in her

initial paraphrase, coupled with the utterance “oh okay, so

kind of “hi”” together suggest that she is

demonstrating awareness of her level of understanding of the French

text. It appeared that Karly was regularly challenging herself to

understand the French text, and then using the English text to check

her comprehension. Though Karly also used other strategies including

focusing on vocabulary in French, it was her paraphrasing

through translation and demonstrations of awareness that

seemed to best characterize her reading of the translated text. It is

also noteworthy that Karly, as seen in this passage, often verbalized

strategies without the researcher’s prompt.

With the integrated text, we

identified 12 distinct strategies with Karly. She again most commonly

demonstrated awareness, doing so a total of eight times.

Similar to the translated text, she reported about her awareness of

difficulty with specific words in French. Though Karly did attempt to

paraphrase through translation in a couple of instances, she

seemed to recognize that without the English equivalent passages, she

would need to rely on a number of other strategies to build meaning.

As seen in Table 4, strategies including asking questions, use

of structure, invoking prior knowledge, and use of

cognates were reported with the integrated text, but not with the

translated text. Karly’s reading of the integrated text was

best characterized by the use of multiple strategies together to

understand unclear passages of text. Excerpt 2 illustrates an example

of multiple strategies that Karly used together as an attempt to make

sense of the text:

Excerpt 2

Well, for “ronron, ronron”

I didn’t understand but there was a “purrrr’’

over here and this seems like a sound…So, I’m guessing

this is “purrrr”. So, that helped me understand a little

bit more and she also said it in the other paragraph so…I’m

guessing that means “purrrr.”

In

this passage, Karly demonstrates awareness of some confusion

related to the term “ronron.” This is a focus on

French vocabulary, and Karly reports that she is using the

picture that accompanies the text wherein the cat is depicted

making a “purrrr” sound. Karly infers that it

“seems like a sound” based on what she has pieced

together from various textual clues and her interpretation of them.

She also uses context cross-linguistically by recalling that

the same term was used in an earlier paragraph. After the integrated

text reading, Karly shared that she needed to rely on different

strategies in the absence of having an equivalent English passage to

assist her in building meaning—this dynamic approach to reading

this style of text was evident throughout her reading and reporting

with the integrated text.

Discussion

In

sum, across the three cases, the differences among Kaya, Maria, and

Karly in their repertoire of strategies used offer a glimpse of their

approaches to reading. In considering how these three focal

participants compare as readers, one might consider that they

position themselves on different parts of a continuum of bilingual

reading development. On the one side of the continuum, Kaya

represents a reader that does not seem to make adjustments to how

they read text based on the demands of the text. Further, Kaya uses a

limited range of strategies. While the reasons for Kaya’s

notable lack of adjustment and range are unclear, this unresponsive

style of reading is considered to be less effective than more dynamic

and responsive approaches (Matheson & MacCormack, 2021; Paris &

Jacobs, 1984). In another part of the continuum, one that

demonstrates a more effective use of reading strategies, reading is

characterized by greater responsiveness and range. Maria represents a

more dynamic reader—one that uses different strategies based on

the style or structure of the text she is reading. Despite greater

range and responsiveness, reading strategy use is mostly monolingual

for her during the interview that took place as she was reading. In

the retrospective interview, she did mention that both English and

French could be used to understand words in the other language,

though such cross-linguistic strategies were not apparent as she

read. At the other end of the continuum, reading is dynamic and it

involves a range of strategies, but it represents a shift to a

heavier reliance on cross-linguistic strategies. As noted by

researchers (Alsheikh, 2011; Jiménez et al., 1996), such

behaviours can be quite effective because they involve reading

strategies that combine L1 and L2 linguistic skills.

Though

our measure for comprehension has not been validated as it was

designed for the two texts we used in the study, the results may

offer some additional insight. Kaya, our first focal student, scored

8 out of 15 in her total reading comprehension score. Maria and Karly

scored 13 and 14 respectively, suggesting that their dynamic reading

styles seemed to lead to greater comprehension. Further, Kaya scored

6 out of 8 with the translated text, but only 2 out of 7 with the

integrated text. Kaya’s lack of adjustment in her approach to

reading the integrated text supports the idea that reading can be

effective when readers transfer strategies across their L1 and L2

(Bourgoin, 2015), but that perhaps it is not effective when the

approach does not match the demands (Mokhtari & Sheorey, 2002).

Karly and Maria had similar overall scores; however the noted

difference with Karly’s proclivity for offering unprompted

reports of her reading activity may distinguish readers of this

study. When readers are comfortable using a mix of monolingual and

cross-linguistic strategies, they may be more confident in using them

as we saw with Karly.

Another interesting result that

emerged from this study is about the need for prompting. Unlike Maria

and Kaya, Karly did not require any prompting while reading, and

instead offered unsolicited verbal reporting of her thinking

throughout the reading of both texts. While she was able to respond

to questions following each passage about her thinking, she also

reported about her thinking within passages. This could have been the

result of stronger language abilities, particularly within the French

language, and therefore, greater confidence in comparison to her

peers. Also compared to her peers, Karly used a greater range of

cross-linguistic strategies. While Karly and Maria used a comparable

number of strategies across both text types, Maria relied mainly on

monolingual strategies, where Karly used both monolingual and

cross-linguistic strategies across both texts. Surprisingly, Karly

was the only participant who reported speaking exclusively English at

home.

Limitations

Like all studies, ours have

limitations that we must put forward. Considering the exploratory

purpose of the research and the limited number of focal students we

described for this paper, our objective was not to showcase an

exhaustive portrait of reading strategies for dual-language text; the

typology we used will likely have to be completed and nuanced as

other researchers zero in on how bilingual students engage in

dual-language reading. In this perspective, we did not focus on our

focal readers’ general competency level in reading, nor did we

situate them in regard to their peers’ reading levels. Future

research focusing on dual-language reading could thus zero in on the

reading strategies used by proficient and less effective readers as

they engage with dual-language books. That way, we will be able to

comprehend the strategies that are predominately deployed by stronger

readers and provide teachers with concrete ways to helps their

students as they read dual-language text. Our focal readers,

moreover, happened to be all girls. Subsequent research should

examine both male and female students to obtain a broader

representation of how children learn and interact with dual-language

texts.

In this study, students had to read

the integrated book immediately after they read the translated text.

We also did not tell students about the structural differences

between each book before they started reading the second one. It is

thus possible that some of the participants did not have the reflex

to adapt their reading behaviours as they engaged with the integrated

text. That being said, as we know that efficient readers tend to

adapt their strategy more easily (Mokhtari & Sheorey, 2002), this

procedure allowed us to document the adaptation of our participants’

reading strategies as they read different types of dual-language

books. Finally, it is important to note that the measures we designed

for reading comprehension of each text type have not been validated.

While they may offer additional insight into the reading profiles of

our focal students, we do not contend that they can serve as

stand-alone measures of reading ability.

Implications

and Conclusion

In

their efforts to support the bilingual reading development of their

students, we suggest that French immersion teachers should encourage

students to draw on their L1 as needed. It is evident from our

results that readers, as seen with Maria, can be dynamic, but largely

monolingual in the strategies they use. Given the identified value of

drawing on both L1 and L2 skills when learning an L2 (Ballinger,

2013; Swain & Lapkin, 2013), we argue that teachers should model

how they make adjustments to their reading behaviour based on the

text, as well as how they use cross-linguistic skills to construct

meaning while reading. Further, teachers could explain their thinking

behind their approaches and actions in order to show students both

how and why they approach reading as they do. We believe that such

practices will not only support students in the development of

reading skills in French, but that they will also help them

understand the potential of cross-linguistic reflections as they read

both monolingual and dual-language text.

References

Alsheikh, N. O. (2011). Three readers,

three languages, three texts: The strategic reading of multilingual

and multiliterate readers. The Reading Matrix, 11(1),

34–53.

Anadón, M.,

& Savoie-Zajc, L. (2009). Introduction. Recherches

qualitatives, 8(1), 1–7.

Anastasiou, D., & Griva, E.

(2009). Awareness of reading strategy use and reading comprehension

among poor and good readers. Elementary Education Online, 8,

283–297.

Armand,

F., Gosselin-Lavoie, C., & Combes, É. (2016). Littérature

jeunesse, éducation inclusive et approches plurielles des

langues. Synergies

Canada,

9,

1–5. https://doi.org/10.21083/nrsc.v0i9.3675

Aydinbek,

C. (2021). The effect of instruction in reading strategies on the

reading achievement of learners of French. Eurasian

Journal of Educational Research,

91,

321–338. https://doi.org/10.14689/ejer.2021.91.15

Ballinger, S. (2013). Towards a

cross-linguistic pedagogy: Biliteracy and reciprocal learning

strategies in French immersion (Unpublished doctoral

dissertation). McGill University, Montreal, Canada.

Bourgoin, R. (2015). Reading

strategies: At risk and high performing immersion learners. CARLA

Immersion Project Research to Action Brief, September 2015.

Retrieved from

http://carla.umn.edu/immersion/briefs/Bourgoin_Sept15.pdf

Brunelle, J., & Tondino, T.

(2017). Enchantée/Pleased to meet you! Montreal,

QC: Les images de la libertée/Lady Liberty Pictures.

Cisco, B. K., & Padrón, Y.

(2012). Investigating vocabulary and reading strategies with middle

grades English language learners: A research synthesis. Research

in Middle Level Education, 36(4), 1–23.

Cormier, G. (2018). Portraits of

French secondary education in Manitoba (Unpublished doctoral

dissertation). University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada.

Cummins, J. (2008). Teaching for

transfer: Challenging the two solitudes assumption in bilingual

education. In N. H. Hornberger (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Language and

Education (2nd ed., pp. 65–75). Springer.

Domke, L. M.

(2019). Exploring dual-language books

as a resource for children’s bilingualism and biliteracy

development (Unpublished

doctoral dissertation). Michigan State University, USA.

Duff, P. A. (2008). Case study

research in applied linguistics. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Edwards, V., Monaghan, F., &

Knight, J. (2000). Books, pictures, and conversations: Using

bilingual multimedia storybooks to develop language awareness.

Language Awareness,

9(3),

135–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658410008667142

Ernst-Slavit, G., & Mulhern, M.

(2003). Bilingual books: Promoting literacy and biliteracy in the

second-language and mainstream classroom. Reading

Online, 7(2),

1–15.

Fleuret,

C., & Sabatier, C. (2019). La littérature de jeunesse en

contextes pluriels : perspectives interculturelles, enjeux

didactiques et pratiques pédagogiques. Recherches

et applications,

65,

95–111.

Frid,

B. (2018). Reading

comprehension and strategy use in forth- and fifth-grade French

immersion students (Unpublished

masters thesis). Western

University, London, Canada.

Gosselin-Lavoie, C.

(2016). Lecture de livres bilingues par

six duos parent-enfant allophones du préscolaire : description

des lectures et des interactions et relations avec l’acquisition

du vocabulaire (Unpublished master’s

thesis). University of Montreal, Montreal, Canada.

Jacobs, H., & Duvernois, C.

(2006). Chez Betty & Cat at home. Hennie Jacobs.

Jiménez, R.,

Garcia, G. E., & Pearson, D. P. (1996). The reading

strategies of bilingual Latina/o students who are successful English

readers: Opportunities and obstacles. Reading Research Quarterly,

31(1), 90–112.

Lau, K.- L. (2006). Reading strategy

use between Chinese good and poor readers: A think-aloud study.

Journal of Research in

Reading, 29, 383–399.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9817.2006.00302.x

Matheson I. A.,

& MacCormack, J. (2021). Avoiding

left-to-right, top-to-bottom: An examination of high school students’

executive functioning skills and strategies for reading non-linear

graphic text. Reading

Psychology, 42(1),

1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702711.2020.1837313

Mokhtari, K., & Sheorey, R.

(2002). Measuring ESL students’ awareness of reading

strategies. Journal of Developmental Education, 25, 2–10.

Moore,

D., & Sabatier, C. (2014). Les approches plurielles et les livres

plurilingues. De nouvelles ouvertures pour l’entrée dans

l’écrit en milieu multilingue et multiculturel. Nouveaux

c@hiers de la recherche en éducation,

17(2),

32–65. https://doi.org/10.7202/1030887ar

Naqvi, R.,

Thorne, K. J., Pfitscher, C. M., Nordstokke, D. W., & McKeough,

A. (2012). Reading dual language books: Improving early literacy

skills in linguistically diverse classrooms. Journal

of Early Childhood Research,

11(1),

3–15. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1476718X12449453

Paris, S. G., & Jacobs, J. E.

(1984). The benefits of informed instruction for children’s

reading awareness and comprehension skills. Child

Development, 55(6),

2083–2093. https://doi.org/10.2307/1129781

Perregaux, C.

(2009). Livres bilingues et altérité. Nouvelles

ouvertures pour l'entrée dans l'écrit. Figurationen,

9(1-2), 127–139.

Read, K.,

Contreras, P. D., Rodriguez, B., & Jara, J. (2021) ¿Read

conmigo?: The effect of code-switching storybooks on dual-language

learners’ retention of new vocabulary. Early

education and development,

32(4),

516–533. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2020.1780090

Robertson, L. H.

(2006). Learning to read ‘properly’ by moving between

parallel literacy classes. Language

and Education,

20(1),

245–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500780608668709

Simoncini, K., Pamphilon, B., &

Simeon, L. (2019). The ‘Maria’ books: The achievements

and challenges of introducing dual language, culturally relevant

picture books to PNG schools. Language,

Culture and Curriculum,

32(1),

78–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2018.1490745

Sneddon, R. (2009). Bilingual

books—Biliterate children: Learning to read through

dual-language books. Trentham Books.

Swain, M., & Lapkin, S. (2013). A

Vygotskian sociocultural perspective on immersion education: The

L1/L2 debate. Journal of

Immersion and Content-Based Education,

1(1),

101–129. https://doi.org/10.1075/jicb.1.1.05swa

Taylor, L. K.,

Bernhard, J. K., Garg, S., & Cummins, J. (2008). Affirming plural

belonging: Building on students’ family-based cultural and

linguistic capital through multiliteracies pedagogy. Journal

of Early Childhood Literacy,

8,

269–294. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1468798408096481

Thibeault, J., &

Matheson, I. A. (2020). The cross-linguistic reading strategies used

by elementary students in French immersion as they engage with

dual-language children’s books. The

Canadian Modern Language Review,

76(4),

375–394. https://doi.org/10.3138/cmlr-2019-0071

Thibeault, J., &

Quevillon-Lacasse, C. (2019). Trois

modalités de réseaux littéraires pour enseigner

la grammaire en contexte plurilingue. OLBI

Working Papers,

10,

291–310. https://doi.org/10.18192/olbiwp.v10i0.3393

Turcotte, C., Giguère, M.-H., &

Godbout, M.-J. (2015). Une

approche d’enseignement des stratégies de compréhension

de lecture de textes courants auprès de jeunes lecteurs à

risque d’échouer. Language

& Literacy, 17(1),

106–125. https://doi.org/10.20360/G2SW2B