Better Together: The Role of Critical Friendship in Empowering Emerging Academics

Courtney A. Brewer and Taunya Wideman-Johnston, Western University

Mike McCabe, Nipissing University

Authors’ Note

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Courtney A. Brewer, Email: courtneyannebrewer@gmail.com and Taunya Wideman-Johnston, Email: taunyawjohnston@gmail.com

Better Together: The Role of Critical Friendship in Empowering Emerging Academics

In this article, we explore how critical friendship can serve to empower emerging academics as they manage the multiple roles and expectations associated with graduate and contract academic work. Critical friendship was operationalized in our study as an authentic friendship between people with mutual understanding of one another’s career context and aspirations (Baskerville & Goldblatt, 2009; Wideman-Johnston & Brewer, 2014). We use Noddings’ (2006) ethic of care as a theoretical and conceptual framework to ground the study. We used narrative inquiry to illuminate how critical friendship was enacted during turbulent times experienced in our emerging academic careers. The findings indicate common experiences in the emerging phases of academic work, including seeking employment, managing roles as graduate students, dealing with tensions in the workplace, and managing logistics of personal life events as they pertain to the workplace. Moreover, an overall theme of empowerment was evident throughout the data and informs the benefits of critical friendship for emerging academics. Our study transforms utility-based understandings of critical friendship (Swaffield, 2003; 2004; Swaffield & MacBeath, 2005) into a model that is based on trust, provides necessary care, and empowers emerging academics as they pursue both individual and collective goals.

Critical Friendship as a Concept in Education Contexts

Critical friendship as a concept emerged in the 1970’s and was considered to be an activity related to self-appraisal (Storey & Richard, 2013). The concept was further developed by Costa and Kallick (1993) who defined critical friendship as follows:

A trusted person who asks provocative questions, provides data to be examined through another lens, and offers critique of a person’s work as a friend. A critical friend takes the time to fully understand the context of the work presented and the outcomes that the person or group is working toward. The friend is an advocate for the success of that work. (p. 50)

Further, in the context of education, Costa and Kallick (1993) operationalized critical friendship as a formalized process that includes a set conference time for the critical friends to meet and a six-step process for conferencing:

1. The critical friend learner shares their practice.

2. The critical friend asks questions to further understand and add clarity to the context.

3. The critical friend learner shares the intended outcomes for the conference.

4. The critical friend provides thoughtful feedback that will support elevating the work.

5. The critical friend asks questions and critiques the practice to offer alternate perspectives.

6. Both critical friends reflect independently and write.

Limited research has been done on the role of gender in critical friendship. Behizadeh et al. (2019) utilized critical friendship groups to develop problem solving and reflective practices for preservice teachers. The participants in Behizadeh et al.’s study differed in genders. The researchers’ found that gender did not influence how preservice teachers reframed obstacles in educational contexts, and showed how critical friendship can be a significant tool to interrupt ideas and practices in educational contexts such as deficit based views of students.

Swaffield (2003; 2004) and Swaffield and MacBeath (2005) took up the concept of critical friendship through several scholarly projects, situating critical friendship within the field of educational leadership, particularly in K–12 schools. Swaffield’s work with critical friendship has added volume to the literature about critical friendship, though as Gibbs and Angelides (2008) pointed out, Swaffield’s definition of critical friendship does not sufficiently honour the true nature of friendship. Where Swaffield and MacBeath (2005) asserted that critical friends can be implicated in formal school evaluations (and that trust in a critical friendship can be developed over 2 days of “intense” relationship building, Swaffield, 2004), Gibbs and Angelides turned to a history of philosophical debate and reasoning about what a “friend” entails. Swaffield (2004) did admit that critical friendships work better when the friend is authentic rather than “imposed” (p. 273). Gibbs and Angelides argued that Swaffield’s understanding of trust is more of a contractual agreement than actual trust, which would be needed in a true friendship. Gibbs and Angelides suggested that Swaffield’s version of critical friendship offered inferior advantages compared to an actual friendship and offered a hierarchy of relationships that they believed better defined the various types of interactions Swaffield suggested. These included critical friendship, critical companionship, and critical acquaintance. Gibbs and Angelides (2008) proposed that critical friendship can be defined as:

Critical friendship is based on friendship where the participants mutually critique their practice. This critiquing is within the nature of their friendship, which extends prior to and beyond the specific of the critique. The worthiness of the critical intervention is based on trust and respect for the vulnerability and wellbeing of both partners who have mutual concern, status and regard. The critique is made with its purpose being the critiqued. (p. 222)

Gibbs and Angelides (2008) supported Swaffield’s position of situating critical friendship within the school, but concluded that the goal of a critical friendship (within a school) is “a long-lasting, engaging and loving relationship with the school” (p. 223).

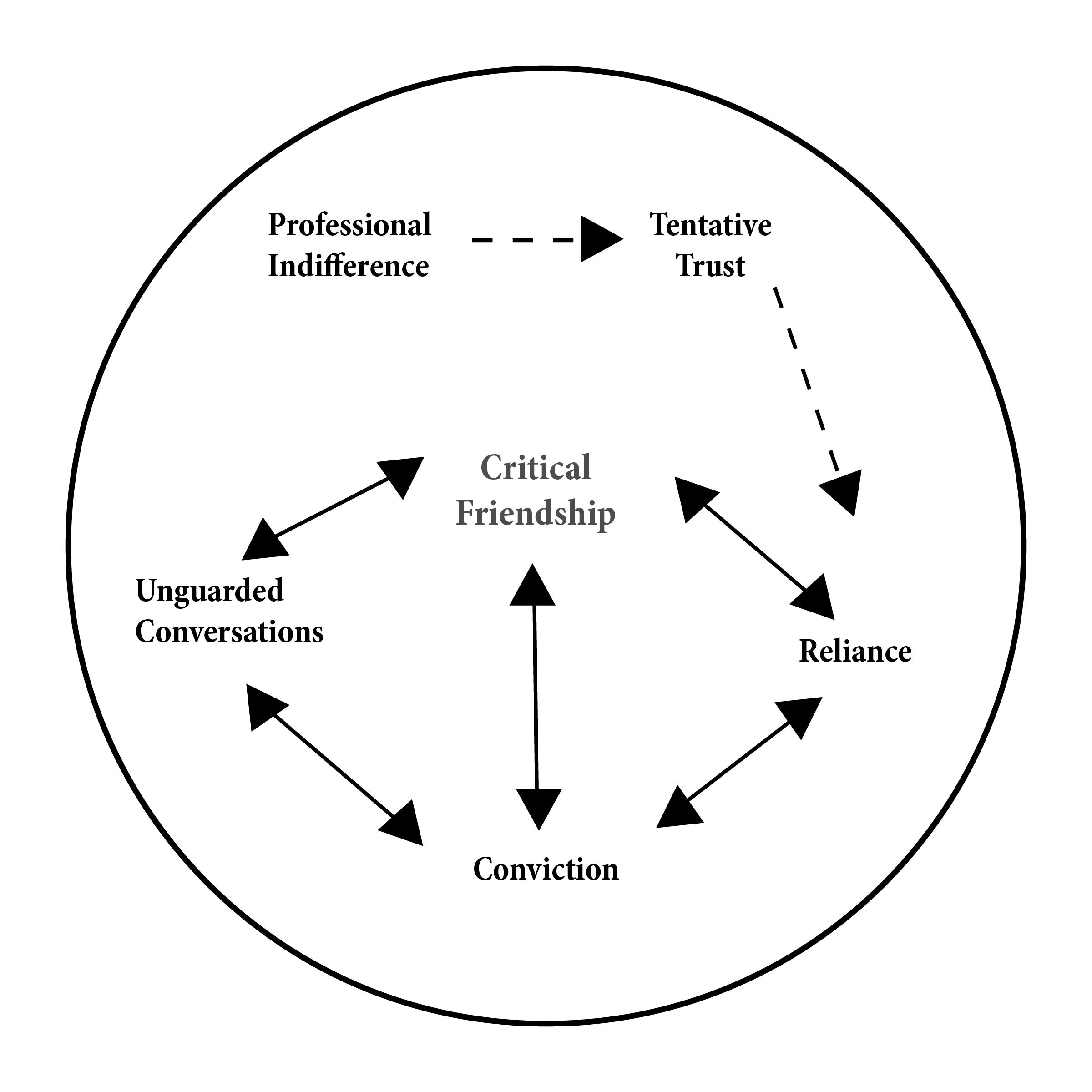

Baskerville and Goldblatt (2009) added more to the research about critical friendship by offering a model of how a critical friendship develops. The authors described their journey to critical friendship when they were working as teacher advisers in New Zealand. They grew into critical friends and used the techniques of critical friendship as they advised teachers in their practice. Their definition of a critical friend is “a capable reflective practitioner (with integrity and passion for teaching and learning) who establishes safe ways of working and negotiating shared understandings to support and challenge a colleague in the deprivatisation of their practice” (p. 206). Baskerville and Goldblatt (2009) frequently cited Swaffield’s (2003; 2004) work on critical friendship and although they seemed to theoretically understand critical friendship as a formal process, their evidence speaks to critical friendship being more of an organic and authentic process than they initially positioned it. Baskerville and Goldblatt (2009) stated that “the choice of a critical friend arose naturally as a result of a team of people working together towards a common goal” (p. 215) and explained that after they realized they were critical friends, they turned to Swaffield to better structure their work together. Baskerville and Goldblatt’s (2009) phases of developing a critical friendship included the following: (a) professional indifference, (b) tentative trust, (c) reliance, (d) conviction, and (e) unguarded conversations.

Wideman-Johnston and Brewer (2014) furthered the development of the concept of critical friendship by refining the concept into the academic field, suggesting that the phases operated in a cyclical way, and that entrance into the cycle of critical friendship growth depends on the status that each member of the friendship holds. The literature about critical friendship revealed that some scholars tend to favour the “critical” function of a critical friendship, while others balance both concepts.

Precarity and Incivility in the Academy

In situating critical friendship in the academic field, it becomes necessary to explore the literature pertaining to the context of precarious work in higher education (with an emphasis on contract academic work as it applies to this current study) as well as critical friendship in action in academic settings. Heffernan and Bosetti (2021) researched the presence and implications of incivility in higher education settings between faculty. Incivility is described as bullying by “smart bullies who know what bullying is and how bullying is identified by university policies” (Heffernan and Bosetti, 2021, p. 1). Incivility in academic settings is increasing across all levels within the university setting. Research indicated a sustained disconnect between universities existing as an educational institution and as a corporate setting with faculty being defined by “performative and quantifiable measures” (Heffernan & Bosetti, 2021, p. 3). Enslin and Hedge (2019) described the neoliberal university setting as a capitalist market-driven place where academics are pushed to perform better and do more each iteration of performance appraisals. Enslin and Hedge (2019) turned to literature about friendship to validate their claim of being friends beyond a utility need and that their friendship, though not “ideal” according to Aristotle, is “real.” Though they did not label their friendship as a critical friendship, Enslin and Hedge (2019) did advocate for friendship in the academic setting that mirrors many of the elements of a critical friendship, noting: “Concomitantly we have indicated that it can entail generative intellectual and moral activity and growth through trusting and honest reflection on, for example, ideas of practice and principles in research and scholarship and teaching and learning” (p. 394). Turning to contract academic work as self-identified racialized early career academics (ECAs), Mbatha et al. (2020) described their roles in such a context as being undervalued, highly competitive, lacking guidance, and disposable. They noted, “Overall, more often than not, we feel overwhelmed, confused, isolated, and sometimes even inadequate as we grapple with teaching, research, service, and having to complete our doctoral studies” (Mbatha et al., 2020, p. 33). Mbatha et al. talked about attaining their positions because they were exceptional students but as soon as they entered the role, they became void of a voice within their institution. They stated, “We argue that institutions of higher learning should approach ECAs with an intersectional approach and avoid seeing them as individuals without doctorates and thus, underqualified; but rather, allow them the opportunity for growth without being stifled, suppressed, and marginalised” (p. 41). In developing a critical friendship over time as a group of four early career academics, they were able to share information to support one another in their growth and success as scholars. They were also not bound to pervasive values for competition as scholars within the same field: “Normally in a competitive and individualistic environment, the different stages would have created a hierarchy. But within the critical friendship, we embrace and see intersectional differences as an opportunity to learn from each other” (Mbatha et al., 2020, p. 37). Friendship, in these studies, was used to buffer against the hegemonic, individualistic, competitive, and demanding landscape of contract academia in neoliberal university settings.

Intersectionality in Critical Friendship

Scholarship about intersectionality (Carbado et al., 2013; Crenshaw, 1989; 1991), within critical friendships is sparse (Mbatha et al., 2020). Clarke and McCall (2013) imagined that intersectionality can be recognized and studied in identities beyond race and gender and within each classification, there are additional intricacies of identity creating one’s position in a given setting. Clarke and McCall (2013) also argued that intersectionality is evident in social sciences research even though it is not explicitly named as such, and explain how intersectionality can move beyond being a definition to being thought of as a process within research. Mbatha et al. (2020) noted their work as ECAs was tied up in intersectionality related to age, gender, race, culture, and inexperience in scholarship and teaching. Adding to the realities and possibilities of intersectionality in academia, Young et al. (2012) stated that Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples need to attend to their relational responsibilities to “begin to trace the intergenerational narrative reverberations of colonization continuing to shape the curricular, the institutional, and the structural narratives” (p. 49). Further, Wideman-Johnston (2016; 2020) shared her narrative of being a woman with a disability working as a contract academic. Through Wideman-Johnston’s adversities related to gender, fertility, disability, and precarious work status, she reframed stereotypical understandings of chronic illness to bring attention to the individual intersectionalities and uncertainties that come from being an emerging academic.

The academic space continues to privilege the voices, opinions, and interests of the dominant. In the research we have explored for this study, the dominant refers to male (Mayhew & Rydstrand, 2019; Mbatha et al., 2020), White (Crenshaw, 1989; 1991), able-bodied (Wideman-Johnston, 2016; 2020), individualistic (Mayhew & Rydstrand, 2019), competitive (Enslin & Hedge, 2019), and tenured (Enslin & Hedge, 2019; Mbatha et al., 2020) people. Like Clarke and McCall (2013), we imagine many other areas of intersectionality within the context of precarious labour in the academy and we bring an assumption that intersections outside of the dominant players will continue to marginalize aspiring scholars. This assumption is highlighted by Cranston (2019) who stated,

Almost self-indulgently, we want to believe, or maybe even convince ourselves, that if we listen carefully and take in someone else’s story, then we have contributed to their betterment, and the world’s by simply paying attention, listening, and then celebrating their resilience. Comforting sentiments such as these ring hollow in terms of social change. (p. 90)

Critical friendship offers an opportunity for marginalised emerging academics to embrace the context they are in and find ways to mitigate the neoliberal conditions of the academy while supporting one another to make positive change in each of their academic careers.

Feminist Approaches to Critical Friendship

Studies focusing specifically on critical friendship from feminist perspectives were not found in our literature search; however, there was research that incorporated the values of friendship in academic settings, and studies about critical friendship such as Mbatha et al. (2020), which describe disparities experienced by female scholars in neoliberal academic contexts. In an article about academic friendship, Mayhew and Rydstrand (2019) described their friendship in an academic setting by describing a significant event—the giving of a poster depicting a feminist author that both scholars cherished—and using the significance of the event and poster to explain their friendship. The authors focused on “risks” associated with collaborative academic settings, including being seen as less-than-capable compared to the “model of lone masculine genius” (Mayhew & Rydstrand, 2019, p. 287). Mayhew and Rydstrand wrote their paper on the premise that risks would need to be taken to both engage in an academic friendship, and to advocate for the benefits of such collaboration, especially between females who continually have more to lose and less to gain. Mayhew and Rydstrand (2019) stated:

Collaborating with her on this project has made me a better scholar—more creative, open and adventurous—and I want to acknowledge how powerful that is in an industrial climate that operates on a logic of competition. In this context, collaboration with the enemy—the rival early career researcher—is undertaken in joyful shared defiance. (p. 288)

Furthermore, Noddings (2006) described the ethic of care with feminist approaches to educational philosophy, though Noddings clarified that caring should not be considered a feminine or women’s ethic. Within the ethic of care, the ultimate goal is to promote natural caring and to do this, Noddings repeatedly turned to the need for trusting relationships and mutual agreement on what caring and cared-for represents in a given relationship. More attention to feminist perspectives on critical friendship is needed.

A Model for Critical Friendship in Academia

Our experience (Wideman-Johnston & Brewer, 2014) was that our critical friendship blurred the lines between professional and personal contexts and offered strength to our abilities in both. We recognized that power imbalances can contribute to different entry points in the trust building aspect of developing a critical friendship as proposed by Baskerville and Goldblatt (2009) and that our critical friendship existed in a cyclical manner where we revisited each phase beyond trust so that the friendship was in continual growth and serving the changing needs of each critical friend (see Figure 1). Therefore, we reject Swaffield’s construction of critical friendship. Swaffield’s concept of critical friendship assumes trust can be built quickly and that critical friendships are developed as a means to an end, with a clear goal and timeline fixed to the relationship that ultimately concludes. We take an authentic approach with equitable emphasis on the “friendship” aspect of a critical friend, similar to what Gibbs and Angelides (2008) suggest. In an effort to reconcile the varying constructions of critical friendship with our own experiences and purposes, we situate our understanding and experience of critical friendship in Noddings’ (2006) explanation of the ethic of care. In the ethic of care, there is a focus on trusting and caring relationships. Noddings (2006) stated that “ethical caring’s great contribution is to guide action long enough for natural caring to be restored and for people once again to interact with mutual and spontaneous regard” (p. 222). We suggest that the development of a critical friendship should be cradled in the ethic of care, but that the full experience of being in a critical friendship is ideally the fulfillment of care beyond a prescribed ethic.

Methodology

We utilized narrative inquiry to make sense of our experiences as emerging academics. Our research question for this study was “What is the role of critical friendship for emerging academics?”

Narrative Inquiry

This research study is rooted in narrative inquiry (Clandinin & Connelly, 2000); an interdisciplinary methodological approach. Clandinin and Connelly (2000) defined narrative inquiry as, “a way of understanding experience” (p. 20). According to Polkinghorne (1988), narrative functions as a means for people to give meaning to their experiences. Furthermore, narrative is a way for people to understand their lives through their actions and the occurrences of episodic daily events. In other words, narrative inquiry allows researchers to make sense of the connections between the personal understanding of experiences, the role of our co-constructed relationship, and the sociality of contexts one finds themselves situated in (Clandinin, 2013). Narrative gives a framework for one to understand the past circumstances of one’s life and make plans for the future. Through narrative, individuals are able to bring together many events and relate the significance of each to one another. Narrative meaning is not static, has the capacity to evolve, and is continuously reconfiguring through “reflection and recollection” (Polkinghorne, 1988, p. 15). Narrative is an ongoing interaction between one’s cognitive schemes and what is happening in the environment. One’s awareness involves, “timely human actions [that] are linked together according to their effect on the attainment of human desires and goals” (Polkinghorne, 1988, p. 16). We utilized narrative inquiry as a means to study our individual experiences of being emerging academics and the role of our critical friendship. Connelly and Clandinin (2006) stated, “Narrative inquiry, the study of experience as a story, then, is first and foremost a way of thinking about experience. Narrative inquiry as a methodology entails a view of the phenomena” (Connelly & Clandinin, 2006, p. 477). Our stories are grounded in being emerging academics and how we mitigate the complexities associated with academia by employing the ethic of care.

The Context of Our Critical Friendship

To further illuminate our experiences as emerging academics, it is necessary to situate ourselves. We both identify as women. Taunya’s status as a woman is intersected with chronic illness, and therefore, she carries an identity as a person with a disability. At the time of this study, we worked at a small regional campus in a Faculty of Education in southern Ontario, Canada. We were both engaged in contract academic teaching at the campus that served approximately 700 teacher candidates, working as research assistants for most of the full-time faculty at the campus, while actively pursuing full-time doctoral studies each at different universities, though Taunya was in the process of transferring to take studies at the university we both worked at. We met when Taunya was in her first year of teaching and Courtney was a Master’s student working as a research assistant. Eventually, we were both hired for the same research project and our friendship began to develop. As time went on and we became more proficient researchers and instructors, our friendship transformed into a critical friendship (Wideman-Johnston & Brewer, 2014). We taught some of the same courses, took on most of the same research contracts, and applied to many of the same doctoral programs to study in. In many ways, we could be seen as each other’s competition, though we never felt this way personally. Members of the faculty we worked in and people in our personal lives had started to compare and contrast us in many ways (asking, wondering, and describing who was teaching more, who got accepted to programs first, how prestigious each of our doctoral programs were). Our perspectives of one another were opposite to the competitive context that surrounded us. We had not engaged in viewing one another as a competitor. We were not willing to put forth the “typical” level of deception required in “typical” professional relationships when we were both hoping for similar successes. It is this dissonance that inspired this study. We wanted to know how our engagement in a critical friendship that employed an ethic of care (even when the messages we were receiving were focused on reasons we should “watch our backs” and “look out for ourselves”), affected how we responded to difficult situations as we continued to emerge in the academic context.

Data Collection

The data in this research study came from narratives that we had created (Polkinghorne, 1988). These narratives were focused on our experiences in navigating difficult situations as emerging academics. Each author had 1 month to compose written narratives. Narratives were used as a means to delve into the complexities of our research question. As a way to develop an inquiry, Clandinin and Connelly (2000) noted the duality between “inward” and “outward” experiences and, “the task of composing field texts that are interpretive records of what we experience in the existential world even as we compose field texts of our inner experiences, feelings, doubts, uncertainties, reactions, remembered stories, and so on...” (p. 86). We developed loose guidelines to compose reflective journals about the nature of the critical friendship between us. The narrative reflected back in time, could focus on any number of situations, could be as vague or in-depth as deemed necessary or appropriate by the writer, and the severity of the situation had to be based on personal perception. When the narratives were composed and completed, we exchanged copies and shared copies with another trusted colleague on our research team. We used thematic analysis to code the data and understand the content of the narratives. As we read through both narratives several times to deconstruct the data and illuminate themes that emerged from the two narratives (Ellis, 2004), we moved from our narratives being field texts to research texts (Clandinin, 2013). Relying on methods by Punch (2009), we engaged in a process of summarizing, documenting, organizing, analyzing, and synthesizing until small units of meaning were collapsed into larger ideas, and eventually, themes. Utilizing narrative inquiry for this study gave us the opportunity to “come to new understandings” (Clandinin & Connelly, 2000, p. 89) about our critical friendship and its role in growing an ethic of care (Noddings, 2006).

Findings

After coding the data, a set of contextual themes indicated the common experiences we noticed in the precarious field of our emerging academic work. These contextual themes included: seeking employment, dealing with tensions in the workplace, managing logistics of personal life events as they pertain to the workplace, and managing our roles as graduate students. Furthermore, a central theme—empowerment—persisted throughout the narrative data. Each of these themes were situated in the “unguarded conversations” stage of critical friendship development and helped to establish examples of the ethic of care in action.

Seeking Employment

While we were working as contract academics and doctoral students, we continued to look for steady employment. We could not rely on teaching the same courses each year as we had low seniority and any changes in student numbers would mean we were out of a job. We also wanted employment that would allow us to pursue our own research rather than relying on contract research work, which at times positioned us as “ghost writers” and left us with little to add to our curriculum vitae. Our research and writing skills were improving and we were outgrowing the complacency we once felt with devoting the majority of our time to research projects that did not serve our aspirations. We had committed to the path of academia, even though we had our own needs for health benefits and desired a financial savings plan such as a pension. We were trained teachers who had entered into academia for different reasons, and it seemed demoralizing to us at times to be earning less than what we could make teaching in elementary school, which would also have provided us with flexible work options, job security, health benefits, maternity leaves, and a pension plan. We often discussed these issues and supported one another in seeking employment, even when it meant sharing a job posting that we would both like to apply to. Our narratives revealed specific references to seeking employment and the feelings we had about the ongoing process of looking to secure work. For example, Courtney’s narratives explained, “Taunya and I are very committed to obtaining full time employment as quickly as possible; but in the meantime, our critical friendship has provided a source of security while we face constant uncertainty.” As well, Taunya’s narrative stated, “Whenever Courtney and I find a job that each of us qualifies for we send each other the position and say ‘We should apply for this!’ Never has it crossed my mind to apply for a job without Courtney; I don’t see her as my competition but as someone who truly deserves the opportunity to shine at that particular position.” At this time, the field of education was saturated with teachers seeking employment and we had grown accustomed to seeing friendships bruised by jealousy over one member securing a job while another remained on the occasional teaching list. We knew we wanted to avoid this in academia, which was proving to be even more competitive. We knew that eventually, both of us would gain some sort of desired employment and as long as we supported one another, we could not only keep our friendship intact, but also we could help one another thrive. We edited each other’s resumes and cover letters, sent each other job postings, and provided guest lectures for each other’s classes. We found that in acting as a source of unwavering support for one another, we made gains in our careers that we could not have done on our own. Taunya secured a job working at a local college and Courtney began to be more specific about the conditions of her research contracts so they would contribute to the growth of her curriculum vitae.

Dealing With Tensions in the Workplace

We greatly valued the autonomy of being emerging academics. We had the opportunities to choose which research contracts we would work on and had the flexibility of catering our schedules to meet our individual needs. We were experiencing our first few years of teaching at the post-secondary level and found it to be very rewarding. We were so committed to what we were doing that we wanted to ensure we continued to do everything “right.” We wanted to make sure we handled all obstacles in the best way possible to ensure future research and teaching opportunities. When we experienced obstacles, we would problem-solve together. We would offer each other different perspectives and solutions to aid the other. Excerpts from our narratives speak to the way we worked together to resolve dissonance and difficulties in the workplace. Courtney described a particularly difficult situation:

We have worked together to carefully craft a professional email to explain how I am feeling to a colleague; in other situations, we have discussed how deeply an issue has been affecting me and have come up with coping strategies and even exit strategies.

At one point, after completing a teaching contract that was renewed for the following academic year, Taunya was required to take a medical leave that left her with many questions about her future employment. She worried how taking one leave would continue to impact her in years to come. She wrote: “What about taking time away from research contracts? Will I no longer be offered these opportunities in the future? I remember telling Courtney I had to take a [medical] leave and we spent much time discussing how I would proceed.” Whether we supported each other in writing professional emails or navigating health obstacles, we were invested in each other’s success. We relied on a strong sense of trust to confide our worries, insecurities, mishaps, and next steps in one another. We knew how important our own and each other’s aspirations were and we worked hard to help each other respond to difficulties as they arose. In doing this, we were enacting the ethic of care to promote resilience in our workplace.

Managing the Logistics of Personal Life Events as They Pertain to the Workplace

The implications of being a contract instructor not only had an impact on our work life but it also affected our personal lives. The decisions we made in our personal lives continued to affect our livelihood. Once Taunya had taken her medical leave it meant giving up her job security and she worried if and how this could negatively affect her career. By having such a trusting and supportive critical friend, Taunya did not experience all of the obstacles associated with taking a medical leave:

As a contract instructor, taking a medical leave also meant unemployment and no longer getting paid. This was another critical situation in my life as an “on-hold” aspiring academic. I found this stressful as I wanted to continue to aspire but also, in regards to the financial strain on my family, I worried about how I would be able to “delve” back into teaching and being a research assistant. Courtney could have chosen to exclude me from further opportunities as I had been away for a year but when the time came she was happy and willing to update me to continue as though I had never been away.

Courtney described the value of critical friendship in general terms during difficult times:

We continued to support each other’s endeavours and we continued to plan for both of our needs. There were times when we faced barriers and things did not go as planned. Times when we were disappointed and felt rejected from a world that we were trying so hard to be a part of.

Courtney also described the delicate task of applying for jobs in the same field, and at times, applying for the same position:

Taunya and I spent a lot of time discussing our options during this time but our security as friends and our commitment to each other’s careers meant that we made the best choices for our needs and supported one another every step of the way, even if it was not convenient and even if rejections and acceptances of one another stung at times. The end result was that we ended up where we needed to be and having a critical friend throughout the entire process made the sting much less intense.

Our critical friendship continued to offer us a safe space to work through the obstacles we faced and gave us the opportunity to offer comfort to one another, help find solutions to problems, and offer much needed perspectives.

Managing our Roles as Graduate Students

The decision to pursue our doctorates was filled with uncertainty. We knew we wanted to pursue doctoral studies, that it was integral to our continuation as academics, and that we had specific research interests we wanted to explore through the type of intensive study that a dissertation journey provides. We took the process of applying and completing our doctoral studies for granted at first but quickly learned that we were not on linear paths. From the initial application process to figuring out what the best program of study was for each of us, we faced challenges, mixed emotions, and rejection in various forms. Courtney delayed her studies to pursue what she truly desired and Taunya ended up changing schools altogether to ensure her medical needs could be adequately met. Data extracted from our narratives helps to highlight the journey we took in attending doctoral studies. Courtney described a time when she had to decline an offer to a graduate program and accept an offer from a school she initially did not imagine attending:

I needed to make a choice based on what was best for me ... I took an offer from a school that just seemed to work well for my needs as a student ... It was also nice to have someone who was truly happy for me when I made my decision. Taunya understood the ins and outs of each choice I was presented with and so knowing that she valued my final decision made it much more meaningful.

Taunya described the challenges associated with being a student while everyone else in her life had moved into flourishing, linear careers:

Courtney and I are both pursuing our PhDs and I feel she is crucial to my sanity in continuing this endeavor. We have sent many texts to each other asking for advice and asking, “This is worth it, right?” As we see many of our friends persevering in their lives, we are still “students” trying to get jobs, completing schoolwork, trying to make ends meet, and pursuing our familial lives.

In our roles as doctoral students, our critical friendship continued to flourish as we navigated our developing research program. Our love of research and our desire to advance scholarship in our chosen fields was met with some disillusionment and harsh realities. Taunya had to come to terms with relocating her studies to a university that had a better record of accessible learning and Courtney had to come to terms with choosing to decline an offer that was not providing her with what she had hoped for in a graduate studies program. After talking through our values related to our doctoral studies and our options in moving forward, we were able to confidently make decisions that ended up steering us into very rewarding research programs.

Empowerment as Emerging Academics

No matter what contextual issue we faced as emerging academics, we knew that our friendship had provided the care needed to resist the neoliberal academic workplace. We were invested in each other and were completely empathetic to the other’s needs. The trust that we built in our critical friendship ultimately empowered each of us in our lives even when our contexts were less than ideal. We acted as carers and cared-fors (Noddings, 2006) by building each other up when needed and acting as each other’s champion during difficult experiences. We also celebrated the progress each of us had made in our academic journeys and in our personal lives because as time had shown us, the world of academia is fairly anticlimactic and we both had the insider knowledge to recognize that what might seem like something small to a person looking in, was actually the result of a lot of hard work and struggle. Paired with the life events that we were transitioning in and out of, the ethic of care established in our critical friendship helped us achieve what we wanted in our careers without having to sacrifice the type of personal life we wanted for ourselves. For Taunya, this looked like spending the first summer of a two-summer residency program in a college dorm while pregnant for the first time. While she was homesick and physically ill from her pregnancy she was trying to conceal, Courtney made a 5-hour drive to visit with her and leave a few larger clothes behind to get Taunya through the last few weeks of her stay. For Courtney, this looked like navigating the transition into living on her own and beginning a relationship with the person who would eventually become her life partner, while also balancing her entrance into doctoral studies. We celebrated big events like marriages, births, funding acceptances, and publications, as well as small things like finally finding the right words to label a theme we had coded, figuring out how to hyperlink a table of contents, and successfully passing an ethics application. Our critical friendship empowered us to feel celebrated as whole people, rather than existing in bracketed worlds where our personal and professional selves always remained at an arm's length. Our critical friendship was the bridge that brought coherence to the fragmented academic path we were centred in, cradling our whole-person journeys. The following data from our narratives illuminates the empowerment that superseded the obstacles we continued to endure as the result of incivility and marginalization in academia. Courtney talked about having an ally in her academic journey:

I think what the most important thing is about our critical friendship in this situation is that I have someone that I can turn to who has likely experienced a similar situation, who can offer sound advice, and who will not make me feel inadequate.

Taunya explained the empowering shift from identifying as a student to identifying as a scholar: “We have come a long way in our research experience from when we completed our Master’s ... we had a bit of an illuminating moment when we both acknowledged that we need to stop thinking of ourselves as solely students.” Further, Courtney described the empowerment she felt from being in a trusting friendship that she could use to help problem-solve in the workplace:

Having someone to talk to about these situations in confidence was important to how I felt in my own workplace. Without these conversations and the trust I have within my critical friendship, my ability to thrive as a researcher in my greater network of colleagues may not have taken place.

Finally, Courtney described her growth as a contract instructor in large part because she had someone to provide guidance and perspective along the way:

I know that I am a much stronger researcher and teacher because of my critical friendship with Taunya and I also know that this friendship has given me the skills and perspectives needed to face many of the future challenges that are likely to arise in my field.

In every obstacle we faced and every step we made forward as emerging academics, our critical friendship promoted the ethic of care to provide us with feelings of empowerment set against the backdrop of incivility and marginalization. Our thoughts and feelings were validated and we grew more confident in the various roles we embodied.

Discussion

Through narrative inquiry, we have examined our critical friendship and recognized the empowerment in our experiences as emerging academics. We return to Noddings’ ethic of care and our own critical friendship development model (See Figure 1). The narratives we contributed to this research were written under the pretext that we were already critical friends and were interested in learning more about how critical friendship was operating while we worked as emerging academics. Our narratives allowed us to turn both “inward” and “outward,” as (Clandinin, 2013) explained:

Turning inward, we attend to our emotions, our aesthetic reactions, our moral responses. ... Turning outward, we attend to what is happening, to the events and people in our experiences. We think simultaneously, backward and forward, inward and outward, with attentiveness to place(s). (p. 41)

Our narratives weaved our internal individual lived experiences with our critical friendship as a relationship within the social reality of the academy and daily life.

Figure 1

Process of Developing and Maintaining a Critical Friendship

Note. Our critical friendship existed in a cyclical manner where we revisited each phase beyond trust so that the friendship was in continual growth and serving the changing needs of each critical friend.

In revisiting the critical friendship development model (Baskerville & Goldblatt, 2009; Wideman-Johnston & Brewer, 2014), the cycle of reliance (working towards a common goal without fear of faltering), conviction (the recognition and commitment to the friendship while managing our responsibility towards our own and each other’s work), and unguarded conversations (the ability to balance the integrity of our friendship while also feeling confident and safe in saying what needs to be said in order to help each other take necessary steps in meeting work goals) was still taking place, but the bulk of our growth stemmed from the unguarded conversations phase of our critical friendship. Our narratives focused on the conversations we had with one another at various points in our academic pursuits, and often, our narratives were so meaningful to our journeys that they are ingrained in our minds and have formed the basis for how we now approach incivility and marginalization.

The reliance and conviction phases (as well as the professional indifference and tentative trust phases which were not necessary for our own enduring critical friendship when we collected data for this study) are cradled in Noddings’ ethic of care. Noddings (2006) stated:

The ethic of care requires each of us to recognize our own frailty and to bring out the best in one another. It recognizes that we are dependent on each other (and to some degree on good fortune) for our moral goodness. (p. 225)

At each obstacle, life transition, and even success that we faced, we were, in Noddings (2006) words, “frail.” There was always the possibility that one member would disclose information and be met with coldness or a self-serving response by the other, as incivility in academia nurtures. However, our deep sense of trust, which Noddings suggests, requires several years to develop, has given us the ability to offer ourselves up as frail individuals, experience empowerment through our critical friendship, and persist stronger than we were. The fullness of our critical friendship after years of working together and journeying through our academic lives as complete beings is so deeply rooted in care, that we believe it embodies Noddings’ understanding of “natural care,” which is no longer reliant on an ethic to guide it. Noddings (2006) explained that, “Ethical caring’s great contribution is to guide action long enough for natural caring to be restored and for people once again to interact with mutual and spontaneous regard” (p. 222). We see critical friendship as an important way of enacting an ethic of care in the academic setting. As Mbatha et al. (2020) stated, “Nosipho’s story exemplifies the dilemmas we have experienced as ECAs, where we have been marginalised due to age, gender, lack of experience, and even culture” (p. 32). Similar to Mbatha et al. (2020), in times when we were met with isolation, self-doubt, par-for-the-course criticism, and continued obstacles, our critical friendship held us to respond in caring ways and to seek care from one another. The cyclical aspect of our friendship model became so fluid that worry about how the other would respond to any given situation was replaced with trust that a caring response would always result.

Conclusions

Positioned against the backdrop of academic incivility, the neoliberal market-driven academy, and the continued privilege afforded to dominant beings (lone, male, white, settler, able, tenured), our study employs critical friendship as both an act of resistance and a harbour for growth. With parallels to our own research on critical friendship, Cranston’s (2019) research illuminates the importance of “allies” continuing to bring forth alternate stories:

People who have suffered from conflict or who are under forms of oppression, need allies who can help them get their stories out into a wider sphere. They need people who are committed to bring their experiences and their stories, out of the shadows and into the light. (p. 98)

This work is an attempt to bring our story of a better way forward, “out of the shadows” (Cranston, 2019, p. 98). Our narrative inquiry shows that critical friendship has the potential to empower emerging academics to thrive while rejecting the neoliberal conditions and incivility that currently mar the academy. By using critical friendship to enact the ethic of care, we hope to shift critical friendship from being a means to an end in professional development (as suggested by Swaffield, 2003; 2004; Swaffield, & MacBeath, 2005) to one that builds enduring trust, fuels empowerment, and ultimately, provides sustained care to each member, and as a result, to the entire academic profession.

Our study helps to fill in the gap of feminist approaches to critical friendship while also building an important bridge between incivility in academia and the ethic of care. Further, with a documented understanding of how intersectional voices are frequently met with hostility and barriers, our work shows that critical friendship can serve as an act of resistance to the dominant narrative that is rooted in the academy. This research shares the stories of emerging academics who are supporting each other in finding power within themselves in an institution that often leaves them powerless. Critical friendship offers the means by which emerging academics can change their narratives. We imagine critical friendship as having the potential to reveal how relationships in the academy can be fostered to empower the growth in individuals, and to demonstrate the possibilities of what can be achieved together.

References

Baskerville, D., & Goldblatt, H. (2009) Learning to be a critical friend: From professional indifference through challenge to unguarded conversations, Cambridge Journal of Education, 39(2), 205–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057640902902260

Behizadeh, N., Thomas, C., & Behm Cross, S. (2019). Reframing for social justice: The influence of critical friendship groups on preservice teachers’ reflective practice. Journal of Teacher Education, 70(3), 280–296. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487117737306

Carbado, D., Crenshaw, K., Mays, V., & Tomlinson, B. (2013). Intersectionality: Mapping the movements of a theory. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 10(2), 303–312. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742058X13000349

Clandinin, D. J., (2013). Engaging in narrative inquiry. Routledge

Clandinin, D. J., & Connelly, F. M. (2000). Narrative inquiry: Experience and story in qualitative research. Jossey-Bass.

Clarke, A., & McCall, L. (2013). Intersectionality and social explanation in social science research. Du Bois Review, 10(2), 349–363. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742058X13000325

Connelly, M., & Clandinin, D. J. (2006). Narrative inquiry. In J. Green, G. Camilli, & P. Elmore, (Eds.), Handbook of complementary methods in education research. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Costa, A. L., & Kallick, B. (1993). Through the lens of a critical friend. Educational Leadership, 51(2), 49–51.

Cranston, J. (2019). Beyond the classroom: Teaching in challenging social contexts. Lexington Books.

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989, 139–168.

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1300.

Ellis, C. (2004). Analysis in storytelling. In The ethnographic I: A methodological novel about autoethnography (pp. 194–201). Rowman & Littlefield.

Enslin, P., & Hedge, N. (2019) Academic friendship in dark times. Ethics and Education, 14(4), 383–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449642.2019.1660457

Gibbs, P., & Angelides, P. (2008). Understanding friendship between critical friends. Improving Schools, 11(3), 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/1365480208097002

Heffernan, T., & Bosetti, L. (2021). Incivility: The new type of bullying in higher education. Cambridge Journal of Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2021.1897524

Mayhew, L. R., & Rydstrand, H. (2019) Risking the personal: Academic friendship, feminist role models and Katherine Mansfield. Australian Feminist Studies, 34(101), 277–294, https://doi.org/10.1080/08164649.2019.1679019

Mbatha, N., Msiza, V., Ndlovu, N., & Zondi, T. (2020). The academentia of ECAs: navigating academic terrain through critical friendships as a life jacket. Educational Research for Social Change, 9(2), 31–44. http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2221-4070/2020/v9i2a3

Noddings, N. (2006). Feminism, philosophy, and education. In Philosophy of Education (2nd ed.). Westview Press. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2265.2010.00573_44.x

Polkinghorne, D. E. (1988). Narrative knowing and the human sciences. State University of New York Press.

Punch, K. (2009). Introduction to research methods in education. SAGE.

Storey, V. A., & Richard, B. M. (2013). Critical friend groups: Moving beyond mentoring. In V. Storey (Ed.), Redesigning professional education doctorates: Applications of critical friendship theory to the EdD. Palgrave Macmillan.

Swaffield, S. (2003) Self evaluation and the role of a critical friend. Managing Schools Today, 12(5), 28–30.

Swaffield, S. (2004). Critical friends: Supporting leadership, improving learning. Improving Schools, 7(3), 267–278. https://doi.org/10.1177/1365480204049340

Swaffield, S., & MacBeath, J. (2005) School self evaluation and the role of a critical friend. Cambridge Journal of Education, 35(2), 239–252.

Wideman-Johnston, T. (2016). The extraordinary gifts received from living with a chronic illness (Unpublished dissertation). Nipissing University, North Bay, Ontario.

Wideman-Johnston, T. (2020, independently published). The extraordinary gifts: My life with a chronic illness.

Wideman-Johnston, T., & Brewer, C. (2014). Developing and maintaining a critical friendship in academia. Journal of Authentic Leadership in Education. 3(2), 1–7.

Young, M., Joe, L., Lamoureux, J., Marshall, L., Moore, S., Orr, J.-L., Parisian, B., Paul, K., Paynter, F., & Huber, J. (Eds.). (2012). Warrior women: Remaking postsecondary places through relational narrative inquiry. Advances in Research on Teaching (vol. 17, p. iv) Emerald Group Publishing. https://doi-org/10.1108/S1479-3687(2012)17