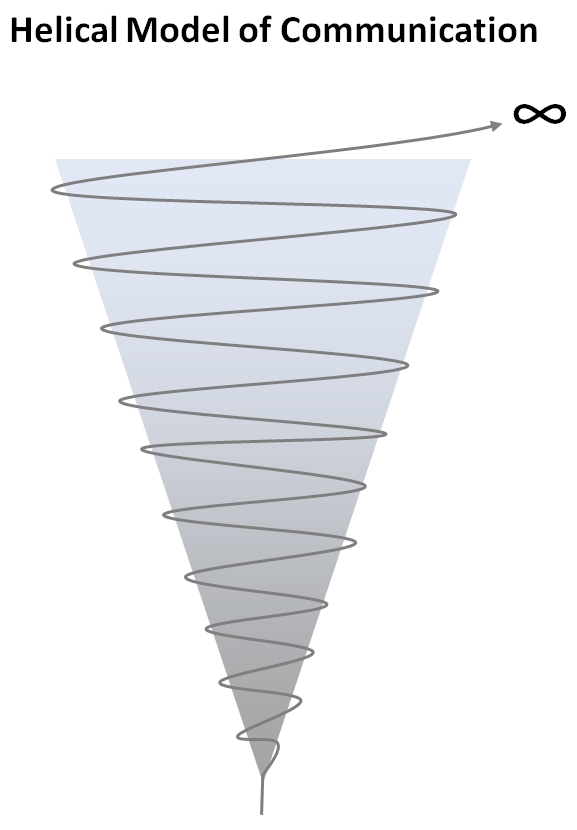

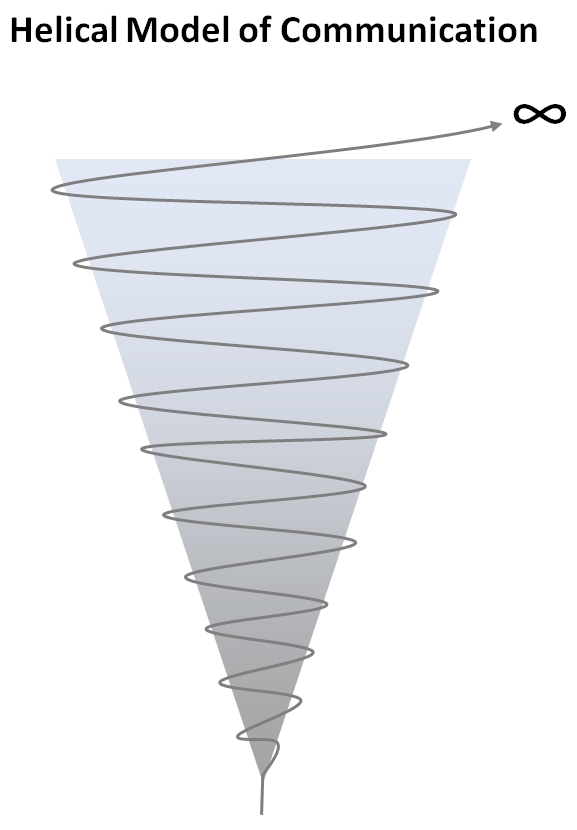

Figure 1: Helical model of communication illustrates communication as a dynamic and non-linear process, and suggests that language acquisition develop and expand with efficacy (figure from Frank, 1967).

Language, Culture, and Pedagogy: A Response to a Call for Action

Paolina Seitz and S. Laurie Hill

St. Mary’s University

Self-Location

We are two researchers, positioned as non-Indigenous, at a small liberal arts university where we teach in the Faculty of Education. We have been working in partnership with Tsuut’ina Education for three years and believe that more meaningful educational opportunities for Indigenous students must be provided. We also acknowledge that these educational opportunities should not be “an ‘either/or’ choice” (Smith, 2009, p. 2) with regards to their own cultural knowledge and more dominant knowledge systems. It is accepted that the larger educational landscape confers credentials that can lead to future success. However, as supported by research (Battiste, 2002; Battiste & Henderson, 2009; Hare, 2010), we affirm that the recovery of cultural knowledge and specifically language is an important imperative linked to the TRC Calls to Action (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015). As settler scholars, we acknowledge that we do not have the same lived experiences as the Tsuut’ina people and so we continually seek to deepen our understanding of the historical and political challenge they have to reclaim their identity and culture.

Our commitment to a diverse and inclusive worldview of education informs our collaboration with the Tsuut’ina Nation. Situated on Treaty 7 land, the institution where we teach is in close proximity to the Tsuut’ina Nation. The impetus for our collaboration began with an invitation from Valerie McDougall, Tsuut’ina Education Director, to assist the district in the enhancement of the Tsuut’ina language and culture. It also grew from an expectation for all of us to respond to the TRCs Calls to Action (2015). Specifically, the project addresses the following principles from Language and Culture 14:

We call upon the federal government to enact an Aboriginal Language Act that incorporates the following principles:

Aboriginal languages are a fundamental and valued element of Canadian culture and society, and there is an urgency to preserve them;

Aboriginal language rights are reinforced by the Treaties; [and]

The preservation, revitalization, and strengthening of Aboriginal languages and cultures are best managed by Aboriginal people and communities. (TRC, 2015, p. 2)

The TRC emphasized the importance of education in their Calls to Action. Universities have an important role to play here. In particular, faculties of education have the capacity to work with Indigenous K to 12 education communities in a collaborative way that has the potential to be mutually beneficial.

The partnership between our Faculty of Education and Tsuut’ina Education focuses on strengthening and revitalizing the Tsuut’ina culture and language with both the Tsuut’ina Gunaha (Language) Institute (hereafter Gunaha Institute) and the Tsuut’ina Education school district, including Kindergarten to Grade 12 schools. In this paper, we discuss the development of a Tsuut’ina language scope and sequence for Kindergarten, age 4 (K4), to Grade 4 students; the development of the Tsuut’ina traditional values framework; and our experiences working with Tsuut’ina Education.

Tsuut’ina Nation has 2,100 registered citizens of which few are fluent speakers of the Tsuut’ina language. Steven Crowchild, director of the Tsuut’ina Gunaha Institute at the time of our project, estimates that there are presently less than 40 people who are fluent in the language. The Tsuut’ina Gunaha Institute was created to assist in the revitalization of the Tsuut’ina language. The Institute’s vision statement explains: “Wusa Tsuut’ina ninayinatigu guts’ina-hi uwa dat?’ishi, t?at’a dzanagu daa?i uwa wusa Tsuuts’ina (Our vision is the full revitalization of the Tsuut’ina Gunaha in all forms, spoken and written, as a legacy to past, present, and future Tsuut’ina People)” (Tsuut’ina Nation Official Website, 2017). The Gunaha Institute mandate states: “The Tsuut’ina Gunaha Institute will focus on the creation of new fluent speakers of the Tsuut’ina language as well as the development of pertinent language resource materials” (Tsuut’ina Nation Official Website, 2017).

Educational research generally confirms the belief that students learn best when their culture and language are part of their classroom experience (Agbo, 2004; Greymorning, 2001; McCarty, 2002). First Nation communities in Canada are currently embarking on a variety of initiatives that will nurture the learners in their communities and preserve their language and identity including the development of culturally relevant materials that reflect the lives of students. Across Canada, “there are 633 First Nation communities…with 11 language families and over 60 language dialects that tend to be specific to local communities” (Chiefs Assembly on Education, 2012). The development of language and culturally informed values in curricular materials is best grounded in particular school environments so that a potential for improvement in educational participation and achievement can be realized (Luke, 2009).

Theoretical Framework

To accomplish our work with Tsuut’ina Education, we considered a number of ethical principles to guide us. Our work was a collaborative endeavour with the language instructors of Tsuut’ina Education carried out with the intent that the collaboration would also benefit the larger Tsuut’ina educational community. We drew from the ethical principles articulated by Riddell, Salamanca, Pepler, Cardinal, and McIvor (2017) who believe these principles to be essential to their research activities with Indigenous communities. Riddell et al. (2019) identified 13 key principles for conducting research with different groups of Indigenous Peoples in a Canadian context, drawn from an analysis they completed of guidelines for conducting research that have been developed by government funding agencies and Indigenous governance organizations. Of the 13 key principles Riddell et al. identified, we selected four principles that were important to us in our working partnership with Tsuut’ina Education. These principles included the understanding that the research: (a) is relevant to community needs and priorities and increases positive outcomes; (b) provides opportunities for co-creation; (c) honors traditional knowledge and knowledge holders and engages existing knowledge and knowledge keepers; and (d) builds respectful relationships (Riddell et al., 2017, p. 7).

Ottmann and Pritchard (2010) wrote, “Indigenous ways of knowing (epistemology) and ways of being (ontology) differ from Western thought” (p. 25). Research has revealed that Indigenous knowledge is “a transcultural (or intercultural) and interdisciplinary source of knowledge that embraces the contexts of about 20 percent of the world’s population. Indigenous knowledge is systemic, covering both what can be observed and what can be thought” (Battiste, 2002, p. 7). Scholars of Indigenous knowledge have recognized the imperative of bringing to their work the understanding that Indigenous people must regain control over Indigenous ways of knowing and being. While our collaboration with the Gunaha Institute instructors did not involve an active research project, we subscribed wholeheartedly to the idea that the interests, experiences, and knowledge of the Tsuut’ina teachers and students must be at the centre of our partnership.

We employed Indigenous theory (Smith, 2000) as a theoretical stance for our work with Tsuut’ina Education, which Smith (in Redwing Saunders & Hill, 2007) describes as one that “includes the use of authentic community voice used to produce a product that is returned to the community for their benefit” (p. 1019). Indigenous theory is based on six principles: “self-determination, validating and legitimating cultural aspirations and identity, incorporating culturally preferred pedagogy, mediating socio-economic difficulties, incorporating cultural structures that emphasize the collective rather than the individual, and shared and collective visions” (Redwing Saunders & Hill, 2007, p. 1020). This theoretical stance informed our perspective in working with Tsuut’ina Education and the manner in which we sought to develop a respectful and trusting relationship with them.

Background to the Project

As mentioned previously, our work with Tsuut’ina Education began with an invitation from the Tsuut’ina Education Director, Valerie MacDougall. We held several meetings over one summer with both Valerie McDougall and Steven Crowchild, Director of the Gunaha Institute. At these meetings we learned that work had been started on the development of a Tsuut'ina Language Program of Studies and it was determined that our role would be to continue the work with a creation of a scope and sequence document that would provide a curriculum framework for the instruction of the Tsuut’ina language for K4 to Grade 4. Tsuut’ina Education believes that they have a shared responsibility along with their community to revive the language that was given to them by their Creator to ensure that it continues to live, grow, and adapt. Through our conversations, it also became evident that protecting and preserving the Tsuut’ina language would not be enough. We determined that the teaching of cultural values must be done in concert with the language instruction. It was agreed that the project would have two complementary themes: (a) the development of a Tsuut’ina Language scope and sequence document and (b) the development of a curriculum template to support the revitalization of Tsuut’ina culture in the K4 to Grade 4 classrooms and life of the school. For the purpose of this paper, our focus will be on the development of the Tsuut’ina language scope and sequence document.

Worldview and Nature of Tsuut’ina Language

“The first principle of any educational plan constructed on Indigenous knowledge must be to respect Indigenous languages” (Battiste, 2002, p. 15). As cited in a Government of Alberta document (n.d.), Walking Together First Nation, Métis, and Inuit Perspectives in Curriculum, Statistics Canada notes that the survival of Indigenous languages is possible only if community interest is present and education programs are available to the community. The worldview of Indigenous people frames their language as a living being that deserves protection (The National Association of Friendship Centres, 2018), thus Indigenous languages are viewed as “sacred and living; ... they contain the words and concepts that embody their ancestral cultures and ways of being” (p. 12).

We wanted to understand the nature of the Tsuut’ina language in order to inform the development of the language scope and sequence. We learned that the Tsuut’ina Gunaha is a part of the Dene Language Family, which is made up of more than 45 languages. “Examples include Ahtna and Tanana in Alaska, Gwich’in, Tłicho and Dene Sułina (N.W.T. & Alberta), Chilcotin, Kaska and Beaver (B.C.), Hupa & Mattole (California), [and] Apache & Navajo (New Mexico & Arizona)” (S. Crowchild, personal communication, July 26, 2016). Further, according to Steven Crowchild, the worldview of the Tsuut’ina language is that the child is the centre, surrounded by the gunaha that gives the child an understanding of his/her life and his/her world. The language is reciprocal in nature; children absorb the gunaha from all around them and from them the gunaha is spoken back to their world. Steven went on to describe the significance of learning the Tsuut’ina language for the community:

Tsuut’ina believe that the identity and spirit of their children is supported and affirmed with the Tsuut’ina Gunaha. The value of learning the Tsuut’ina language and culture both for Tsuut’ina and non-Tsuut’ina students is enormous. It permits insights into a Worldview of spiritual and natural dimensions. When we truly speak our language once more, Elders and their wisdom will again become accessible. The learning of the Tsuut’ina Gunaha will strengthen cultural identity and enhance the self-esteem of every individual. Every individual that knows this truth has a responsibility to lead, support, or assist in some way to protect and preserve the language. (S. Crowchild, personal communication, July 26, 2016)

Through our conversations with Steven Crowchild, we gained a deeper understanding of the Tsuut’ina language and worldview, which was reflected in our work with the development of the scope and sequence.

Development of Scope and Sequence Document

The individual learner is part of the larger social world so the practices of schools and homes are important influences for the learner (Norton, 2013). In many First Nation community schools, the potential engagement of students is limited by the overall rigidity of the curriculum and the lack of connection to First Nation values and history. Redwing Saunders and Hill (2007) argue that to create social justice changes in the community, authentic and equitous education must begin with collaboration between classrooms and the communities of which they are a part.

Previous to our involvement, work had been done between the Provincial Government and Tsuut’ina Education resulting in a document that articulated an overarching development of language learning. We used this document as a resource for the framework to inform the development of a scope and sequence document for Tsuut’ina Education. Also, one author has a background in second language instruction and was familiar with the provincial Second Language Program of Studies.

Having met with Valerie McDougall and Steven Crowchild over the summer to determine the direction of the project, our subsequent meetings were with the Tsuut’ina Gunaha instructors to understand their needs regarding a developmental language instruction document for their students. They identified a need to name topics and grammatical structures to be taught at each grade level to support the developmental nature of language acquisition. They also expressed a desire to be involved in this project and support our work.

We were mindful of creating an opportunity for collaboration and co-creation in the development of the Tsuut’ina language scope and sequence document. As a result, our first step was to develop and present two professional development workshops for the Gunaha Institute instructors. In the first workshop, we engaged the instructors in the development of the Tsuut’ina language scope and sequence framework. Working in groups, instructors identified gaps in their current language curriculum document. We collected their feedback and discussed a potential framework for the development of the Tsuut’ina Language Program of Studies.

The second workshop allowed the language instructors, working in their grade-level groups, to determine student learner outcomes in each grade from K4 to Grade 4. Based on the information that we collected from our second workshop, it was clear that the aim of the Tsuut’ina Language and Culture scope and sequence document was the development of communicative competence and the knowledge, skills, and values of Tsuut’ina Gunaha. In addition, in alignment with Tsuut’ina values and the developmental nature of language acquisition, especially in the early years, we all realized that the focus of the Tsuut’ina Language Program of Studies was on oral communication (Karmiloff & Karmiloff-Smith, 2002).

We believed the provincial Second Language Program of Studies was flexible and reflected best practices in language acquisition. In particular, we adapted the notion of using fields of experiences and organized the learnings at each of the grade levels based on general and specific learner outcomes as articulated in the provincial Second Language document. We adopted these strategies in order to incorporate Tsuut’ina Nation’s ways of knowing and doing.

We began our writing of the scope and sequence document with an acknowledgement of the following assumptions articulated by Tsuut’ina Education:

Language is communication.

All students can be successful learners of language and culture, although they will learn in a variety of ways and acquire proficiency at varied rates.

All languages can be taught and learned.

Learning Tsuut’ina as a second language leads to enhanced learning in both the student’s primary language and in related areas of cognitive development and knowledge acquisition. This is true of students who come to the class with some background knowledge of the Tsuut’ina language and develop literacy skills in the language. It is also true for students who have no cultural or linguistic background in Tsuut’ina and are studying Tsuut’ina as a second language. (Tsuut’ina Education, 2013)

These assumptions gave us guidance in our work and provided direction for the language instructors and their students. For example, for assumption 1, we were consistently aware of the importance of developing communication skills throughout the development of the scope and sequence document.

An additional consideration was that language learning and cultural teachings are developmental in nature (Kimba, 2017) as reflected in the Frank Dance’s (1967) helical model of communication (see Figure 1). The spiral model illustrates that communication is a dynamic and non-linear process, and suggests that language acquisition begins with no knowledge of the language and as learning occurs, the language skills develop and expand with the learner language efficacy.

Figure

1: Helical model of communication illustrates communication as a

dynamic and non-linear process, and suggests that language

acquisition develop and expand with efficacy (figure from Frank,

1967).

As new learning is acquired, it is integrated into the whole of what has been learned before. This model, then, represented for us how the students’ language and cultural learning progress occurs in an expanding spiral.

The scope and sequence document that we created is developmental in nature and recognizes that language learning is a gradual, scaffolded process whereby students are given the opportunity to develop and refine the basic language elements needed to communicate. Each progressive level plays an important role in the development of students’ abilities to understand and express themselves in the Tsuut’ina language. Therefore, each grade is the building block for the next and subsequent grades.

The development of the Tsuut’ina language scope and sequence document reflects current knowledge about second language learning and learner-centred teaching. It rests on a research-based premise that students acquire language knowledge, skills and attitudes over a period of time as their ability to communicate grows (Karmiloff & Karmiloff-Smith, 2002). Presently, language acquisition is taught and learned through a performance-based approach. The repetition of new words is crucial for language acquisition. Through repetition, a toddler learns to speak, and repeated words soon become part of the toddler’s frequent vocabulary. Lilli Kimppa (2017) states, “Frequent exposure to spoken words is a key factor for the development of vocabulary. More frequently occurring (and thus more familiar) words can, in turn, be expected to have stronger memory representations than less frequent words” (p. 1). This current language acquisition knowledge was integrated when developing the scope and sequence framework.

The final draft scope and sequence document was shared with the Gunaha Institute instructors and the director, Steve Crowchild, for their responses and their additional feedback. Overall, the language instructors were positive about the guidance the new document for language instruction offered them. The document clearly identified learning content at each grade level and supported the language instructors in providing a developmentally informed Tsuut’ina language program.

Outcomes

We discuss outcomes from our work through the lens of the four principles identified earlier as guiding our partnership with Tsuut’ina Education. The first principle states that the collaboration should be relevant to community needs and priorities and increase positive outcomes. We responded to the invitation from Tsuut’ina Education to work with the Tsuut’ina Gunaha Institute to explore avenues to revitalize the Tsuut’ina language. Battiste (2002) explains, “Language is by far the most significant factor in the survival of Indigenous knowledge” (p. 17). The priority of the Tsuut’ina Gunaha Institute was to formalize instruction of the Tsuut’ina language and provide guidance and professional development support to the language instructors. As a result, we developed a scope and sequence document for Tsuut’ina language instruction that reflected a developmental approach to language learning. Additionally, we provided professional development workshops to enhance the instructors’ skills in language instruction.

Figure 2. Tsuut’ina traditional values posters

A further positive outcome of this project was the growing number of parents who became aware of their language through conversations with their school age children. The language revitalization process awakened an interest within the school community and the larger community. Students are now greeted by their teachers daily in the Tsuut’ina language. Posters in the Tsuut’ina language that express the Tsuut’ina traditional values are displayed in the classrooms and throughout the school building (see Figure 2). It is of note that Tsuut’ina teachers reported that curiosity from community members is an acknowledgement that the project is promoting and furthering their language.

The second principle states that the collaboration provides opportunities for co-creation in the sharing of decision making, data management, and knowledge. The scope and sequence document was co-created through our work with the Tsuut’ina Gunaha instructors. The process began with us seeking clarity about their requirements. Within those conversations, we identified a need for linguistic components for instruction at each grade level. We incorporated the feedback into the development of a draft scope and sequence document. We worked together with the instructors to complete the final version of the document (see Figure 3). The language instructors gave a final approval to the scope and sequence document.

Figure 3: Tsuut’ina Gunaha Instructors’ Workshop

The third guiding principle articulates that the collaboration honours traditional knowledge and knowledge holders and engages existing knowledge and knowledge keepers. In the development of the scope and sequence document, we honoured the language instructors’ knowledge. Along with Tsuut’ina elders, instructors are considered the Tsuut’ina language knowledge keepers in their community. In addition, the director of the Gunaha Institute engaged community elders in the creation and production of media to support the language learning provided by the scope and sequence document. The language instructors use the videos to enhance their teaching, which gives authenticity to the language instruction and incorporates cultural touchstones.

Finally, the fourth principle states that collaboration builds respectful relationships through respect for cultural norms, knowledge systems, and the sharing of knowledge. We recognized from the start of our partnership that the development of trusting relationships would be essential for the success of the project. We also recognized that we were not the experts. We needed to know and honour the expertise of the language instructors. We took a listening approach and validated many of the skills they brought to the team. A respectful relationship ensued allowing us to create a scope and sequence document that acknowledged and shared their expertise.

These outcomes suggest that language knowledge acquisition leads to and enhances cultural knowledge acquisition (Karmiloff & Karmiloff-Smith, 2002). This cultural knowledge provides students with an opportunity to reflect upon their culture with a view to understanding themselves and their Tsuut’ina community.

Implications

In the following section, we discuss the implications for our work. We do this by focusing on the following three themes that grew from our partnership: reciprocal relationships, shared expertise, and respect for worldviews.

Reciprocal Relationships

Relationships among group members are key to the success of any group project (Kouzes & Posner, 2007), which held true to our experience in our collaboration with Tsuut’ina Education. We responded to the invitation from the Tsuut’ina Education director to be involved in the project, but were initially uncertain about the needs and the goals of the project. We were not previously known to the Tsuut’ina Gunaha Institute personnel and it became evident early in the process that if the project was to be successful, we would need to establish trusting relationships. We drew from our experiences in working on other projects and we reviewed the literature on building positive relationships (Blanchard, Hybels, & Hodges, 1999, Kouzes & Posner, 2007, Hargreaves & Fink, 2011) to confirm our understanding in this area.

Our initial approach was to take a listening stance (Kouzes & Posner, 2007). This included familiarizing ourselves with the role that each of the language instructors played within the schools. We also wanted to be aware of their expertise, as our collective expertise would guide our work together. We began our project at the point of expertise that the instructors already held. It was also important that we understood what they hoped to achieve from involvement in the project. This became a recurring focus for us as we wished to be successful in meeting their needs. We shared each step of how we imagined the project unfolding and requested their feedback. The language instructors consistently engaged in the development of the project and their comments were valuable in moving the project forward successfully. This process of listening and responding allowed for reciprocal relationships between us to develop.

Shared Expertise

It is a human desire to be acknowledged and understood. In our work with the project, we realized the importance of empowering the instructors and of recognizing the expertise that each of them brought to the project. According to leadership theory, this recognition builds accountability and pride within the team (Kouzes & Posner, 2007). We recognized that we were not a solo act; for the project to be successful, we knew we needed a team effort.

We understood that the Tsuut’ina Gunaha instructors added expertise that we did not have. They were among the few community members who could speak the Tsuut’ina language. We felt comfortable in leading the process for the creation of the scope and sequence document, but we were aware of our lack of knowledge of the Tsuut’ina language—an essential skill needed to be successful in this project. We engaged in reciprocative learning (Redwing Saunders & Hill, 2007), actively learning with and from each other.

Indigenous epistemology is relational (Kovach, 2005). We were mindful of continually honouring our relationship with the language instructors. We learned that within an Indigenous axiology, the way the project team interacts with one another is of paramount importance. The sharing of expertise among the members of the project team honours both the Indigenous epistemology and axiology. Minkler and Wallerstein (2003) explain it is essential to involve equally all members in the process and recognize the unique strengths that each team member brings to the project. We believe that the attention we gave to acknowledging shared expertise was a contributing factor in the success of the project.

Respect for Worldviews

We see a need to offer pedagogical approaches that can support the decolonization of Indigenous students, helping them to move successfully into the world. Recent research has suggested that approaches in education that do not acknowledge and align with the holistic and interconnected worldview of Indigenous people are ineffective (Collins, 2004, Redwing Saunders & Hill, 2007). Different ways of supporting students that will recognize and value their understanding can have a positive impact on learning. Battiste and Henderson (2009) have argued that the teaching of Indigenous languages “is the most pressing issue for professionals in educational institutions” (p. 14). Battiste and Henderson (2009) further note, “Comprehending Indigenous languages, their structure, translations, and speaking are central and irreplaceable resources to how IK [Indigenous Knowledge] can be acquired and learned” (p. 14).

We come from an educational system that focuses on a singular truth where disciplines are still largely taught in isolation from each other. This Eurocentric context does not readily support an integrated learning experience for students and “does not adequately prepare our children to be successful in a rapidly changing, globally interdependent world” (Munroe, Borden, Orr, Toney, & Meade, 2013, p. 323). In our work as teacher educators, there is value in offering another perspective on teaching and learning, one that provides students with a way to connect to their learning and to each other. Along with other teacher educators, we have embraced the provincial framework for 21st century learning (Alberta Education, 2011) in our work. These competencies include critical thinking, problem solving and decision making; creativity and innovation; social, cultural, global and environmental responsibility; digital and technological fluency; life-long learning, personal management and well-being; and collaboration and leadership (Alberta Education, 2011, p. 3–5). These competencies resonate with an indigenous worldview that holds that the distinctive features of indigenous knowledge and pedagogy are “a person’s ability to learn independently by observing, listening, and participating with a minimum of intervention or instruction” (Battiste, 2002, p. 15).

While Munroe et al. (2013) suggest that indigenous approaches to education are at odds with a traditional Eurocentric approach, they make the connection that a 21st century skills and competencies approach to learning aligns with indigenous knowledge and ways of knowing. Munroe et al. (2013) recommend that integrating indigenous knowledge can enhance 21st century approaches to teaching. We hope that the alignment these authors suggest between the dominant view of education and indigenous knowledge will reinforce respect for indigenous ways of knowing and the value of new ways of thinking about education.

Future Collaboration

Our work on this project is dependent on our partnership with Tsuut’ina Education. We believe that we have met the four key principles as guidelines for conducting research with Indigenous communities (Riddell et al., 2017) that we identified as important to our work in this project. These four principles will continue to guide our future collaborations with Tsuut’ina Education as we will be sharing our work at conferences and collaborating in writing projects that reflect shared authorship.

Conclusion

The key principles, adapted from ethical guidelines for conducting research with Indigenous communities and adopted by us, guided us in our collaboration with Tsuut’ina Education. We acknowledge the critical role that adherence to these principles played in conducting work with the Tsuut’ina Education community. The principles informed our collaboration and were enacted practically and relationally as we worked together. Further, we discussed three implications from our partnership: reciprocal relationships, shared expertise, and respect for worldviews. Setting a clear communication process was vital in helping us develop reciprocal relationships. We recognized that the participation and engagement of the Tsuut’ina Education personnel allowed them to actively share their expertise. Finally, we appreciated the opportunity to deepen our understanding of decolonization and why further changes are crucial and necessary for Indigenous students.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action has inspired collaboration among educational stakeholders, and universities have an important role to play. “Indigenous education draws on an organic metaphor for learning that includes diversity as an asset, creating spaces to value and nurture multiple forms of knowing and ways of being in the world” (Sanford, Williams, Hopper, & McGregor, 2012, p. 6). Our work with Tsuut’ina Education has offered us a space in which to embrace an alternate way of knowing and the opportunity to appreciate the responsibility that we have to listen and learn from others. We are motivated to revisit and rethink our own practices as teacher educators so that our teaching can reflect both the principles of 21st century education and Indigenous knowledge. It is our hope that the language scope and sequence document and the development of the Tsuut’ina traditional values framework contribute to a meaningful learning environment for all students. These initiatives support Tsuut’ina Education and the larger Tsuut’ina community in the reclamation of their rich cultural heritage.

References

Agbo, S. (2004). First Nations perspectives on transforming the status of culture and language in schooling. Journal of American Indian Education, 43(1), 1–31.

Alberta Education (2011). Framework for student learning. Competencies for engaged thinkers and ethical citizens and entrepreneurial spirit. Retrieved from https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/4c47d713-d1fc-4c94-bc97-08998d93d3ad/resource/58e18175-5681-4543-b617-c8efe5b7b0e9/download/5365951-2011-framework-student-learning.pdf

Battiste, M. (2002, October). Indigenous knowledge and pedagogy in First Nations education: A literature review with recommendations. Prepared for the National Working Group on Education and the Minister of Indian Affairs, Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, Ottawa, ON.

Battiste, M., & Henderson, J. Y. (2009). Naturalizing indigenous knowledge in Eurocentric education. Canadian Journal of Native Education, 32(1), 5–18.

Blanchard, K., Hybels, B., & Hodges, P. (1999). Leadership by the book: Tools to transform your workplace. New York, NY: William Morrow.

Chiefs Assembly on Education (2012, October 1–3). A portrait of First Nations and education. Retrieved from http://www.afn.ca/uploads/files/events/fact_sheet- ccoe-3.pdf

Collins, K. (2004). Growing readers. Units of study in the primary classroom. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Dance, F. E. X. (Ed.).(1967). Human communication theory. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Government of Alberta. (n.d.). Walking together First Nations, Métis, and Inuit perspectives in curriculum. Retrieved from http://www.learnalberta.ca/content/aswt

Greymorning, S. (2001). Reflections on the Arapaho language projector, when Bambi spoke Arapaho and other tales of Arapaho language revitalization efforts. In L. Hinton & K. Hale (Eds.). The green book of language revitalization in practice (pp. 286–297). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Hare, J. (2010, August). They beat the drum for me. Education Canada, 44(4), 17–20.

Hargreaves, A., & Fink, D. (2011). Sustainable leadership. San Francisco, CA: Jossey- Bass.

Karmiloff, K., & Karmiloff-Smith, A. (2002). Pathways to language: From fetus to adolescent. Retrieved from http://ebookscentral.proquest.com

Kimppa, L., (2017). Repetition a key factor in language learning. Science Daily. Retrieved from www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/05/170502084630.htm

Kouzes, J. M., & Posner, B. Z., (2007). The leadership challenge. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Kovach, M. (2005). Emerging from the margins: Indigenous methodologies. In L. Brown & S. Strega (Eds.) Research as resistance (pp. 19–36). Toronto, ON: Canadian Scholars’ Press.

Luke, A. (2009). Introduction: On indigenous education. Teaching Education, 20(1), 1–5.

McCarty, T. (2002). A place to be Navajo: Rough rock and the struggle for self-determination in Indigenous schooling. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Minkler, M., & Wallerstein, N. (2003). Community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Munroe, E. A., Borden, L. L., Orr, A. M., Toney, D., & Meade, J. (2013). Decolonizing aboriginal education in the 21st Century. McGill Journal of Education, 48(2),317–337.

The National Association of Friendship Centres. (2018). Our languages, our stories towards the revitalization and retention of indigenous languages in urban environments. Discussion Paper. Retrieved from https://nafc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/NAFC-Indigenous-Languages-Discussion-Paper-EN-New-Website.pdf

Norton, B. (2013). Identity and language learning: Extending the conversation. (2nd ed.). Toronto ON: Multilingual Matters.

Ottmann, J., & Pritchard, L. (2010). Aboriginal perspectives and the social studies curriculum. First Nation Perspectives, 3(1), 21–46. Retrieved from http://www.mfnerc.org/wpcontent/uploads/2012/11/5_OttmanPritchard.pdf

Redwing Saunders, S. E., & Hill, S. M. (2007). Native education and in-classroom coalition-building: Factors and models in delivering an equitous authentic education. Canadian Journal of Education, 30(4), 1015–1045.

Riddell, J. K., Salamanca, A., Pepler, D. J., Cardinal, S., & McIvor, O. (2017). Laying the groundwork: A practicum guide for ethical research with Indigenous communities. The International Indigenous Policy Journal, 8(2). Retrieved from https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/iipj/vol8/iss2/6 doi:10.18584/iipj.2017.8.2.6

Sanford, K., Williams, L., Hopper, T., & McGregor, C. (2012). Indigenous principles decolonizing teacher education: What we have learned. in education 18(2), 1–22.

Smith, G. H. (2000). Maori education: Revolution and transformative action. Canadian Journal of Native Education, 24(1), 57–72.

Smith, G. H. (2009). Transforming leadership: A discussion paper. Presentation to the 2009 SFU Summer Institute. Vancouver, BC.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). (2015).Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to action . Retrieved from www.trc.ca

Tsuut’ina Education (2013). Tsuut’ina language and culture12-year program. Unpublished manuscript.

Tsuut’ina Nation Official Website. (2017). Tsuut’ina Gunaha Institute. Retrieved from https://tsuutinanation.com/tsuutina-gunaha-institute/