Situating Intergenerational Trauma in the Educational Journey

Rainey Gaywish and Elaine Mordoch

University of Manitoba

This paper discusses a qualitative study exploring Aboriginal students’ perceptions of the impact of intergenerational trauma (IGT), resulting from colonization, inclusive of Indian Residential Schools (IRS), on their educational experience. IGT is the transmission of the effects of adverse life experiences that influence how the individual appraises the world, and can also influence development of ineffective coping skills. The individual who experiences trauma and his or her offspring are at increased risk for further trauma, leading to the first generation’s problems being repeated in the second generation (Bombay, Matheson, & Anisman, 2009). Some recent epigenetic-focused studies indicate that IGT may affect subsequent generation. 1

However, there is no conclusive evidence of transmission of trauma effects in humans. In our roles as administrator and professor in a university program with Aboriginal students, we perceived a critical need to investigate these phenomena to help us understand hardships that some Aboriginal students were experiencing and, in particular, to seek answers to help us respond to incidences of unexplained attrition.

We had observed a chronic pattern of a few students who were failing to submit final assignments despite having performed strongly in the classroom. These were students who had demonstrated interest in their studies, proved to have more than adequate academic skills, and who had also sought out support from instructors and program staff, yet failed to submit final assignments due after classes had ended. Influenced by the implementation of trauma-informed care in health care, we pondered the ideas of trauma-informed education (Mordoch & Gaywish, 2011). Could trauma-informed education and the emerging research on intergenerational trauma be considered together in an effort to understand this observed pattern of student behavior? Although education and therapy are distinct entities, we propose that, in addition to introducing Indigenous content and pedagogy, education must respond to the effects of trauma, both historical and ongoing, within classroom settings. The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (2015) recorded 94 Recommendations for reconciliation, some of which provide significant support for this approach.

Indigenous Methodology

Location of the Researchers

We have worked with mature Aboriginal students from urban and remote areas in an Aboriginal-focused program for more than 20 years. Dr. Gaywish is an Aboriginal scholar and 4th Degree Midewiwin immersed in the study and practice of Anishinabe knowledge traditions. Dr. Mordoch is a settler scholar with expertise in mental health who has both taught and learned from diverse Indigenous students. The research assistant was a mature Aboriginal student, knowledgeable about Indigenous culture, traditions, and contemporary issues affecting Aboriginal people.

The research methodology we adopted is based on an aspect of Anishinabe worldview and an understanding that an Indigenous paradigm comes from the fundamental belief that knowledge is relational. “Knowledge is shared with all of creation . . . It goes beyond the idea of individual knowledge to the concept of relational knowledge” (Wilson, 2001, pp. 176–177).22 The methodology is based in part on the Midewiwin Anishinabe worldview presented in The Mishomis Book: The Voice of the Ojibway (Benton-Banai, 1988), and a 1983 lecture on Anishinabe research methodology by Professor Jim Dumont from Laurentian University as well as on the knowledge and experience of Dr. Gaywish, grandmother and 4th Degree Midewiwin (also known as the Grand Medicine Society of the Anishinabe). The method also draws on the Four Directions Teachings.com (2006).

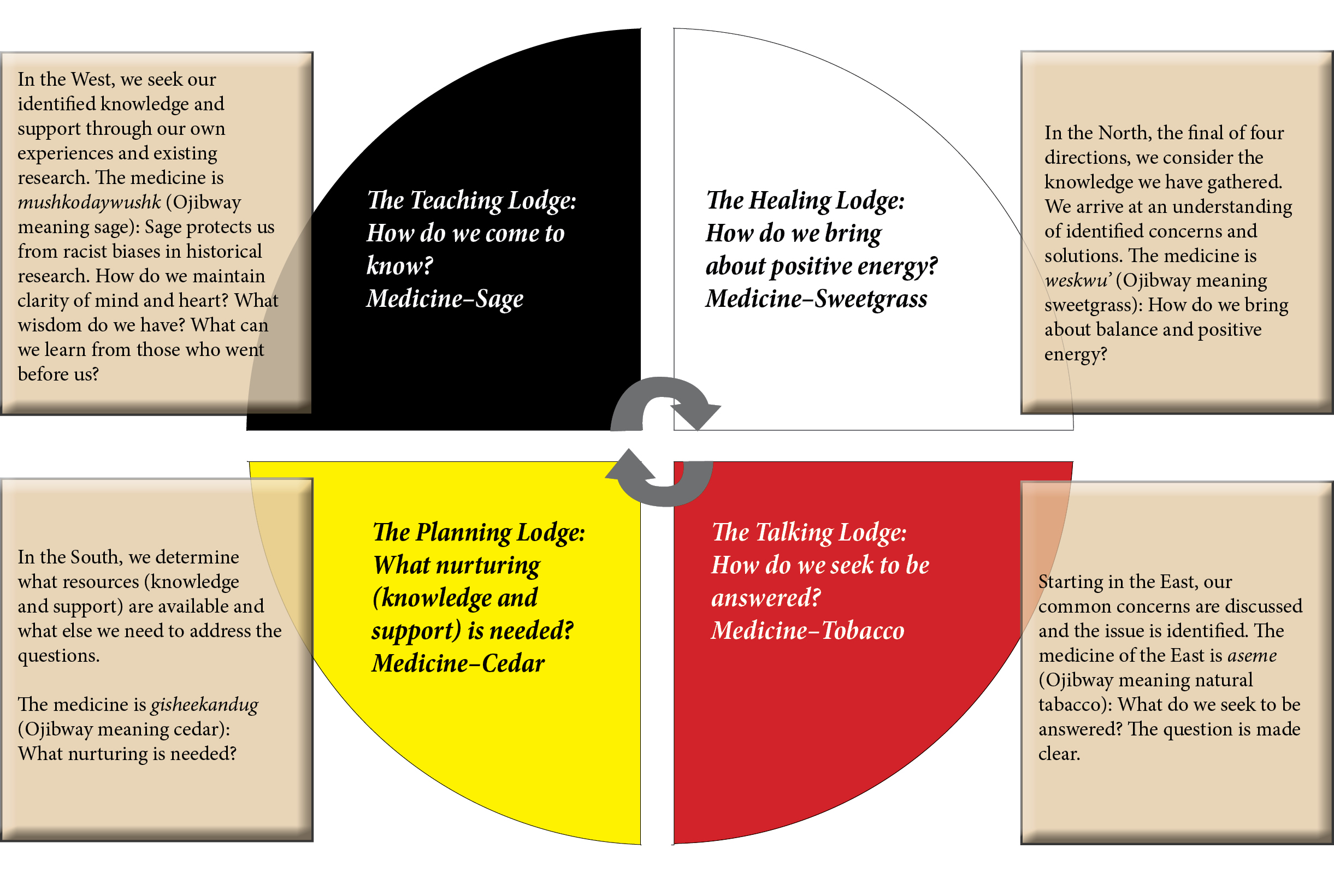

In the study framework, a lodge is situated in each of the four directions: East, South, West, and North. These directions are expressed in the research process as four phases: Talking, Planning, Teaching, and Healing. Each phase articulates a perspective and questions that correspond with the Anishinabe teachings and the traditional medicine of the direction in which it is situated (See Figure 1.) The process starts in the East (situated in lower right quadrant to correspond to directionality and ends with North at the top):

Figure 1. This figure illustrates the Four Lodges, an Anishinabe research methodology that includes four phases beginning in the east and moving to the South, then the West, and finally to the fourth direction, the North (Mordoch & Gaywish, 2011, based on The Mishomis Book: The Voice of the Ojibway, Benton-Banai, 1988), audio recordings at Four Directions Teachings.com 2006, and a 1983 lecture by Professor Jim Dumont, Laurentian University.)33

Application of the Four Lodges to the Research Study

The Talking Lodge: What Do We Seek To Be Answered? Medicine: Tobacco

We begin in the East, the Talking Lodge. Here we discuss common concerns related to the identified issue. The medicine of the East is asema (Ojibway meaning natural tobacco): What do we seek to be answered? (Mordoch & Gaywish, 2011).

We were guided by oral stories students shared over the years as well as our experience of attrition concerning students who were doing well in other academic indicators of successful progress in their studies. The Calls to Action in the Final Report (2015) of Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) echo what we heard from students. The report calls for improved education attainment for Indigenous people and affirms the critical role of education to address the ongoing, intergenerational impact of Indian Residential Schools (IRS), (TRC, 2015).

Trauma-informed services are organized to enable practitioners to recognize trauma, deliver sensitive care, and avoid retraumatization of the person (Elliot, Bjelajac, Fallot, Markoff, & Reed, 2005). Trauma-informed education is offered in some elementary and secondary settings (see for example, www.childhood.org.au); however, it is generally not integrated into post-secondary education. There are many anecdotal accounts of the adverse effects of IRS and IGT on mental health and social issues; however, few empirical studies have been conducted on IGT in Aboriginal people (Bombay et al., 2009) and particularly on IGT’s effects on students’ post-secondary educational journeys. We focused our study on understanding perceptions of IGT and its impact on the progress of students in the post-secondary program in which they were enrolled.

Intergenerational trauma. IGT is a reality in Indigenous peoples’ lives. Adult survivors who recounted statements about the trauma experienced in the IRS were already second- or third-generation survivors of the IRS system. The introductory notes of the TRC’s (2015) Final Report state:

For over a century the central goals of Canada’s Aboriginal policy were to eliminate Aboriginal governments; ignore Aboriginal rights; terminate the treaties; and, through a process of assimilation, cause Aboriginal peoples to cease to exist as distinct legal, social, cultural, religious, and racial entities in Canada. The establishment and operation of residential schools were a central element of this policy, which can best be described as “cultural genocide.” (p. 1)

Yellow Horse Brave Heart, Chase, Elkins, and Altschui (2011) identified the unresolved collective grief related to historical trauma that accompanies mental health and emotional issues of Indigenous people. Bombay, Matheson, and Anisman (2014) stated that long-term effects of the IRS experience inclusive of abuse have resulted in disrupted community and family relationships and self-destructive behavior. Corrado and Cohen (2003, as cited by Bombay et al, 2009), stated that in “a sample of First Nations Residential School Survivors that had experienced abuse, 64 per cent were diagnosed with PTSD” (p. 10). Research supports the assertion that Aboriginal people experience increased risk for PTSD due to high levels of life stress, poverty, and family violence and instability related to ongoing intergenerational trauma resulting from historical trauma (Bellamy & Hardy, 2015).44

Seven Generations prophecy. The teachings of respected Iroquois Elder and scholar Chief Oren Lyons explain the Iroquois Great Law of Peace that contains the Seven Generations teaching.

The Peacemaker taught us about the Seven Generations. He said, when you sit in council for the welfare of the people, you must not think of yourself or of your family, not even of your generation. He said, make your decisions on behalf of the seven generations coming, so that they may enjoy what you have today. (Oren Lyons, Seneca, Faithkeeper, Onondaga Nation)

This Seneca teaching identifies that the responsibility for the next seven generations centers on leadership, vision, and caring. In the traditions of the Anishinabe, the teachings about responsibility describe how actions of one generation resonate into the future for at least seven generations. This is important to consider in relation to the effects of IGT and to educators’ responsibility to redress the hardship of IGT on students.

The Indigenous people, our people, were aware of their responsibility, not just in terms of balance for the immediate life; they were also aware of the need to maintain this balance for the seventh generation to come. The prophecy given to us, tells us that what we do today will affect the seventh generation and because of this we must bear in mind our responsibility to them today and always. (Clarkson, Morrissette, & Regallet, 1992, p. 25)

The time span of seven generations is 150 years. The IRS system operated in Canada from the 1870s to the closing of the last federally run school in 1996. Thus, 150 years from 1996 identifies the impact of IRS into the future for another 130 years (TRC, 2015, p. 1). Our discussions in the Talking Lodge revealed the importance of undertaking this work and its potential effects for the seven generations. Drawing on research on trauma-informed health care, we sought to examine how students perceived their progress and success in post-secondary education was being impacted by IGT. Our hope was to apply what we learned to better inform the support post-secondary institutions provide to Aboriginal students.

The Planning Lodge: What Nurturing (Knowledge and Support) Is Needed? Medicine: Cedar

Information and resources gathered in the Talking Lodge were focused on what approach to take to respond to the broad research question we were asking: How is IGT understood and how is it affecting Aboriginal students’ education? Our observations of students’ progress in the programs in which we were involved revealed that students and instructors/staff of these programs would be the best people to discuss the issue. We resolved to ask how IGT affects students’ educational process in post-secondary education, what problems arise, and what potential solutions might be from their perspective. We chose to use a qualitative research method, which was more appropriate to our research question, to the research participants who were predominantly Aboriginal, and to the available sample size or number of participants. In this second phase, we secured funding and obtained ethical approval, ensuring the research complied with university ethics requirements as well as with SSHRC’s Tri-Council Policy Statement on ethics for research involving First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples of Canada.

We determined that the student participants would prefer to speak with an Aboriginal interviewer and we hired a graduate student in Nursing as a research assistant. She is knowledgeable about Aboriginal history and university studies and was able to engage in sensitive conversations about the research topic. The interviews were conversational, fitting with Indigenous knowledge based in an oral tradition (Kovach, 2010). We recruited the participants by poster and word-of-mouth communication. Students granted us permission to review their academic records. The research assistant debriefed within the research team due to the sensitive nature of the interviews. Upon completion of the project, she visited an Elder to process emotions generated by the interviews. Students were provided with guidance to access a counselor if they felt they needed support in addition to those already available through the programs in which they were enrolled and the Aboriginal Student’s Centre counselors and elders.

To ensure confidentiality, only the research assistant knew the participants’ names and accessed students’ educational records. Interviews were transcribed and identifiers were removed.

The Teaching Lodge: How Do We Come to Know and Attain Clarity of Mind and Heart? Medicine: Sage

In the Teaching Lodge, we studied the participants’ words transcribed from the audio-recorded interviews. The data analysis was comprised of content analysis; identification of key statements, commonalities, and differences among data; and acknowledgment of the relationship of the data to the whole as guided by the Four Lodges framework. To obtain clarity, we worked both independently and collaboratively, meeting many times to discuss the interview conversations and compare our perceptions.

The student sample involved 16 Aboriginal students currently registered in an Aboriginal focus or access university program who had completed at least one year of studies or a program within the last five years. The students were in on- or off-campus access programs. The majority of the students interviewed were parents, or lived in homes in which there were children. The following is a table outlining the student sample descriptors:

Table 1

Student Sample Descriptors

|

Descriptor |

Participants |

|

Gender |

14 females 2 males |

|

Age range |

20–60 years of age |

|

Ancestry |

1 Métis, 4 Oji-Cree, 2 Ojibway, 1 Dene, 5 Cree, |

|

|

3 Aboriginal* |

|

Years in programs |

1–4 years |

|

Living with children |

11 students representing a total of 34 children, aged 1–26 years |

|

Employment |

2 part-time, 6 full-time, 2 volunteer work |

|

Years in program |

1–4 years |

|

Number of Vws |

16 |

|

Number of Aws |

6 |

|

Number of fails |

20 (one student had multiple fails), 3 students failed dueto no paper |

|

Programs |

5 off-campus, 11 access/on-campus |

|

Completed secondary education |

1 B.Sc. 3 Diploma students (60 credit-hour degree credit programs) |

|

Average GPA |

3.05 (range from 2.0 to 4.0) |

*Self-identified as Aboriginal; nonspecific group

The knowledge shared by the student participants. Within the Teaching Lodge, we studied interview conversations to help us understand the issue. Student interviews consisted of eight main questions with related sub-questions that addressed the students’ experiences. We began with reasons for enrollment.

Enrolment. Students explained their reasons for enrolling in their program, citing career days and information from encouraging work and family role models. Some did not identify strong supports and expressed that they were challenged by self-doubt. These students recalled reaching a critical point in their lives that generated a desire for a better future, including being able to have a job and pay the bills. As one student put it:

I just came to a point in my life where I wanted more out of life than just going day to day because I knew that I was capable of doing a lot more than what I was told or believed. And I wanted to break that circle of, of, uh trauma I guess.

Future aspirations. Students had various aspirations linked to their educational goals. Students identified altruistic goals to help in health and child and family services in northern Aboriginal communities and to honor family members who had struggled. Several students wanted to validate traditional knowledge alongside Western knowledge in disciplines such as medicine and art. Students felt their personal life experiences contributed to their capacity for empathy and would help them to be effective helpers in their chosen careers.

The meaning of intergenerational trauma to students. When describing IGT, students spoke of insidious effects that trickled down between people and generations. They described these effects as negative and harmful. One participant referred to,

the filtering down of injury or damage from generation to generation. It’s not a point. It’s not something that happens in a point . . . It’s a spectrum and it carries on; just like ripples in a . . . pond.

Students described IGT as ongoing, passed on to children and grandchildren. Their definitions and their perspective of IGT expressed great sorrow and compelling images of the challenges experienced in controlling its effects on their lives. In one student’s words:

So I describe it as a strainer with all this yucky stuff inside this strainer and it trickles down, thinking that you’re going to hold it all up and you don’t want to give that to your kids. But it trickles down anyway.

The students described IGT affecting both their families and themselves. Some were IRS survivors as well as children and grandchildren of survivors. One student explained how the parents’ trauma is picked up by the children and is transferred to the next generation as different behavior:

I guess I would define it as the effect keeps happening because those feelings that say your parents have going through something traumatic and the kids pick up on that. And I think you manifest it, maybe perhaps not in the same way but it could be through anxiety, or . . . you know, in some cases it was addictions and negative coping.

Students witnessed diverse effects in their families. Many noted lateral violence—physical, emotional, and sexual abuse—that crossed generational lines, with alcohol often involved. One student told this story:

My auntie, she went to the same residential school. My auntie used to hide my mother under the bed while they grabbed her and took her into this room and did a lot of stuff. . . And I remember the time I was sleeping; I must have been like 9. Having a good sleep. All of a sudden I just felt something slap me right across the face. I just felt it . . . . and I seen … my mother walking out the door. And one day, after she left, my auntie told me what they did to her. So it just probably—‘cause it affected her, the trauma, and now she did that to me.

All 16 students interviewed believed they were experiencing IGT effects. Students discussed the damaging effects and their passion to end the cycle of trauma. One student said, “Coming out of IRS, I had no ambition and [I] lacked self-confidence. I wanted to break out of the circle of trauma.” She described her mother as being unable to be affectionate or to say “I love you.” She saw herself reflecting that behavior onto her own child. Another student described IGT effects in the following way:

You can’t believe everything that you think because sometimes it is not the truth. And I thought OK, it really, it made me think about where my life was going and what I was doing that I didn’t think . . . was harmful but it was. Like, um, the communication was really poor with me because I shut myself out a lot.

Many of the students learned about IGT through firsthand experiences that they struggled to articulate. One student noted,

I have a lot of pain and anger, shame. What they did to my mother, she did that to me. So I’ve suffered a lot of emotional, physical abuse. . . . When I say “they,” I said that she went to IRS. All my family went. And her, her mother went. And her sisters, her siblings, all of them all went. But they, when they received their [IRS] monies, it’s like, uh, it’s not enough for the pain they caused her, the dysfunctional family because there’s so much alcoholism. And that’s why we’re so, not close today.

The impact of intergenerational trauma on the students’ educational journeys. As students discussed their experience of IGT and their educational journeys, some disclosed histories of poverty, family dysfunction, child welfare involvement, alcoholism, and drug use in addition to experiences with racism and lateral violence that took place before and during their university studies. For some, IGT was like carrying a burden that could be motivating and conquered. Others described it as overwhelming. Students who were able to see positive effects, such as motivation to succeed, noted that these positive effects were accompanied by painful memories. For some, IGT issues became the driving forces that motivated them to pursue higher education. One student explained,

I applied to get into medicine through a special panel that accepted Aboriginal students, so it was a special interview. And it took me 4 years to get into medicine. I applied every year for 4 years. And in the panel they asked me what it meant to be Aboriginal. And I had no idea. I felt like a real fraud applying to this category. Mainly because I didn’t know anything about my heritage or, um, like all I knew was about comments that I’d had. And I knew that I wanted to change. And I knew that, you know, I didn’t want to live the kind of life. . . . I think things could have been a lot different had my parents had a different view on education and different view about themselves and their heritage.

Students recognized that higher education had previously been unobtainable, and therefore, some parents did not value it; students sometimes felt parents undermined their educational pursuits. One student made the following comment:

Neither one of my parents ever really graduated. So for them, their big goal was just to have me graduate and after that it didn’t matter. . . . I was the first one in my family to ever go to university. . . . But then when I started going to university, it was almost as if they started feeling like, um, like not good enough. Like I was on a different level than them. And so they, all of a sudden, looked at me differently and were almost mean and … put me down to try.

In addition to carrying the burden of IGT as a known risk to their success, students struggled with its effects manifested as self-doubt, feelings of incompetence, living with alcohol and addictions, difficult family dynamics, and difficulty coping with the stresses and challenges of being a student. As one student said, “If you are in, in the middle of a trauma, you don’t have the energy to access support, I don’t think. The personal energy.”

Students experienced difficulty organizing their schoolwork and dealing with personal problems. One student observed, “Because of trauma you kind of have your negative background. So, as a result, you would, um, just get lost in your own work because you kind of procrastinate and do other things instead of actual school work.” Another interviewee commented that in their view, without support, Indigenous people often feel,

incapable of succeeding because they look around them and they see a lot of people are where they are in life, where they feel they should have been. And so, and I feel that with that in mind, a lot of First Nations people don’t have that support. Like the mentors, the people to guide them along the way to get to where they want to go.

The student participants explained that their self-doubt emerged from life experiences wherein they felt put down and faced with expectations, which were lower for them than for non-Aboriginal students. One student described this effect in the following way:

How it affects me, is that I feel that I’m not worth it, you know. I feel like okay, well I’m just another stupid Indian, you know, that I won’t be able to achieve. And then there’s another part of me saying “I can do this. Show these people!”

Students perceptions of IGT in other students’ behaviours. Students recognized behaviors in other students that they attributed to IGT.

Lack of confidence. Students could present as shy, aloof, or fearful of asking questions in class. As one interviewee explained:

Many IRS survivors do not have the confidence in themselves when it comes to being in a learn[ing] environment. This has a lot to do with the severe repercussion and strict discipline observed or experienced when you fail to present your knowledge of instructions. This scenario is a cause for many individual’s lack of reading and writing skills; they are afraid to have that known to instructors, and many will not challenge themselves to learn and/or do not want to be humiliated in front of fellow students.

Family disconnection. Students perceived family disconnectedness as another effect of intergenerational trauma in themselves or fellow students. Many families were described as disconnected and unable to provide meaningful, consistent support. Current and past relationships between men and women were often described as unhealthy, abusive, and damaged by alcohol. Dysfunctional relationships identified as part of the IGT experience had a detrimental effect on students’ progress. Some families interacted only when alcohol was involved. When students had problems with their family relationships, they felt lost, as one student described:

I wish I had what I see what other families have, but I can’t. I wish I was close to my grannie. . . My mom and my grannie never got along. My grannie’s trying to gain that back, but there’s a part of me wanting to hate her because she wasn’t close to her own daughter

One interviewee observed that one student’s struggles in school were attributable to family breakdown:

Like all her family drinks and does drugs, and her brother just got out of jail, um, for doing car thieves and like car stealing. . . . A lot of drugs and drinking, I see a lot of my friends surrounded by and affected by… I guess some people want to be in school too, but there’s a lot of BS around drinking and drugs and having children and men and women not being able to get along that it just, um, hurts their academic success.

Stress triggers. Another student described the impact of intergenerational trauma on students when the stress of academic expectations gets intense. The student reflected that for some students, because their parents—as a result of their own trauma—were unable to instill what they did not themselves possess, their children were vulnerable to react negatively to the pressures and expectations of the academy:

Because of the negativity that comes from such trauma and seeing how their parents weren’t exactly like top-class citizens because of their own problems, I would say that they (students) would lack certain . . . . traits to succeed in university. Like just being organized, being positive. Don’t always be pessimistic. . . . Some students are quite good at hiding it well. But it’s when they get really stressed out, like exam week—that’s when you start seeing the effects of such trauma throughout the generations. You . . . wouldn’t know it as an outsider, but if you witness it yourself, you could recognize it. Usually it’s by they’re just more angry or more negative.

Fragmented identity. As a result of IGT and colonialism, students often knew little about their history. University studies helped students articulate their personal and family experience of IGT. They were emotionally affected as they gained understanding of historical trauma and how it contributed to current problems. One of the participants told the following story:

When I was first learning about Native studies and historical trauma, I got angry. I was blowing up at people and, if a White woman looked at me the wrong way at a store, I just felt a lot of pain. . . . Learning about how unfairly my people were treated makes me angry.

Sometimes family conflicts arose when students were reclaiming their heritage. One student explained that her family members negated their history and belittled her interest. She feared her children would sense this negative stigma toward Natives from their own relatives:

I feel like there’s always that cloud kind of hanging around. And . . . I understand why they feel the way that they do, but it’s just, like, it’s so ingrained in them. I don’t know how to change their views on, you know, Native people aren’t just drunken Indians on the street…. You’re Native and yet you’re not a drunken Indian on the street. And, but to them, they’re not Native. They do whatever they can to not be.

Common factors identified as effects of IGT. The common factors students identified as the personal effects of IGT on their life journeys are listed below:

Adverse childhood experiences including trauma, violence, and abuse;

family disconnection, both current and past, and family service placements;

family communication problems;

personal and family problems with alcohol and drugs;

horizontal violence in families and communities

unresolved anger, shame, grief, and loss;

negative self-concept such as self-doubt, low self-esteem, and low confidence;

ongoing struggles including living with fear, loneliness, hurt, and pain in mind, body, and spirit;

mistrust and racism toward non-Aboriginal people; and

internalized racism and memories of feeling degraded.

Post-traumatic growth has been identified as positive cognitive, emotional, interpersonal, and spiritual consequences that follow a traumatic event (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996). Despite the negative impact of IGT, and although some students said there was nothing positive about it, some students identified positive factors that helped them survive:

Empathy and compassion for others in adverse circumstances,

assertiveness for self and Indigenous rights,

reclamation of Aboriginal identity,

impetus to start the healing journey,

awareness of history and effects on Aboriginal people,

motivation for education,

responsibility to role model for community and children, and

self-discipline.

Issues in the Classroom. Students identified five issues related to effects of IGT in the classroom: fear of stigma, anger and defensiveness, healing needs, insufficient background education, and resentment from community and family.

Fear of stigma. Aboriginal students often felt stigmatized and as if they were viewed differently than other students. Students may feel uncomfortable in class settings and feel that it is not a safe place. One student observed that for some:

they’re afraid to sometimes even come to class, you know. Like that’s what I experienced last year. And, uh, with whom they just were nervous. And it’s kind of, you have to squeeze into a little seat and some of them are, like I said, don’t feel too good about themselves and kind of you don’t see them again.

Anger and defensiveness. Some students are angry and defensive, feeling that other students have had an easier road. One participant said of a student:

He’s very defensive about, um, being Aboriginal. And sometimes people will make comments to him that are relatively innocent, but he’ll read stuff into it. . . . And, yeah, we get a lot of comments, like our education is free and paid for, which it’s not.

Healing needs. Students may not have begun their healing journeys and may be vulnerable to issues that arise, for example when completing personal life maps or watching videos with sensitive content. Class lectures, topics, and assignments can trigger feelings of distress associated with unhealed traumas. One participant acknowledged,

Anger, there’s lots of crying. There’s lots of healing. How else would it come out? Probably in their stories that they write. Their essays. And it’s kind of like a healing journey in this program I find. Yeah. Because you have to express anger.

Another student added:

Most of them are unaware that they have high anxiety because it’s become so normal. It’s been normalized for them. That this is how they’ve dealt with their lives for, you know, 10, 15, 20 years. They’re used to operating at that level

Students reported that some learning assignments helped facilitate healing for them. One student noted:

I did the positive and the negative part of my parents. Um. My dad being the good role model, um, even when they drank, he was funny. My mom was the negative. My dad was Popeye. My hero. Like and then, uh, gasoline colors represented anger. My mom. Like there’s different, and then there’s part where, oh yeah, and then there’s an old dad in a building that looked like it was going to fall down. Well that was our family separating. Like there’s a lot of metaphors in there.

Inadequate educational backgrounds. Students were disadvantaged by their experience of inadequate preparation for university education. Often they had to leave their communities for high school. Students sometimes had not learned good study skills prior to their secondary education, and some of their families did not value education. A participant explained:

Like the studying and working. They just don’t know how; because coming from a community where it’s only from kindergarten to Grade 8, you know, and then that’s basically it. Or else you have to leave your family to come. So . . . many dropped out because they didn’t have that discipline. And then they would have to relocate in order to get their GED and then come back and then they still don’t have that discipline of how to study. It’s just that they don’t know how to kind of thing, because of the, uh, lowered education levels up North.

Similarly, another student offered the following thoughts:

I didn’t have any mentors or people who could help me. And I think that there are a lot of Aboriginal people who have, um, no hope. It’s hard for them to get through school and then what comes after? Like they don’t know. So I think you need a lot of help and guidance to get you through. And to help you. Because, I don’t know, I’m not so sure that our parents are as equipped to help us.

Resentment from family and community. Students perceived that horizontal violence resulting from IGT manifested as resentment from family and community members toward students. In one student’s words, that resentment manifested as,

a lot of lateral violence. A lot of competition. But it just, it just makes me strive even harder to do what I have to do for myself. And to be a better advocate for myself. And it has helped me to stand up and fight for what I want; to say, well I deserve this, because of the fact that I am First Nations and I come from a community.

Parents who had few opportunities for education themselves lacked skills to help their children. Sometimes parents resented it when their children sought higher education and saw those children as becoming like White people and feeling superior. One student described the following:

A lot of students come from families that are like, “You’re just trying to be a White man going to school. And you’re all educated now and you come back to the reserve and . . . ” They think that you think you’re better than them. So there’s like that striving student.

Students’ perceptions revealed the reality of their life situations related to IGT and their education journey. For most, those situations were seen as obstacles.

The Healing Lodge: How do we Bring About Positive Energy? Medicine: Sweetgrass

Within the Healing Lodge, we ask ourselves the following questions: What do we understand about the concerns and solutions related to our research question and how do we bring about positive energy to work with this situation? Intergenerational trauma has far-reaching effects on families, children, grandchildren, and communities of survivors of the IRS (TRC, 2015). Students reported that their parents were often not able to assist and encourage them with homework. Considering that the Indian Affairs 1950 report on IRS documented that only half of each IRS year’s graduating class achieved a Grade 6 level, and that survivors’ accounts report only Grade 3 skills, as well as others that identified not being able to read or write, it was inevitable that the parents who attended IRS would have great difficulty in assisting their children (TRC, 2015, p. 193). The lowest levels of Aboriginal education are reported in areas with the highest levels of residential school survivors, First Nations people living on reserve, and Inuit. In addition, lack of skills and education left the parents in situations of chronic unemployment or underemployment, leading to deeper levels of poverty (with incomes 30% lower than those of non-Aboriginal people) for longer periods, increased violence, and higher prevalence of addictions than among non-Aboriginal people (TRC, 2015).

In the Healing Lodge, given what we know about the healing need, we determine what balance can be brought to address the research problem. To begin, we consider the students’ words and respect their perceptions about how to manage the effects of IGT within education.

Students’ advice for instructors and program planners about the effects of intergenerational trauma.

Acknowledge IGT and effects and build positive relationships. Students noted that the first step is to acknowledge IGT and its effects in the classroom. Developing personal relationships with students and inquiring about how they are doing, listening, and reaching out to them are all efforts that are appreciated. Within classes that address personal sensitive experiences, students must feel safe. These classes often help students in their personal healing and thus in attaining their career goals. As one interviewee noted:

Instructors, program planners, need to realize the reality of intergenerational trauma affects everybody; it’s very real and alive. As survivors of IRS, many are beginning to acknowledge the traumatic effects; however, there are no resources on the local level to assist in moving forward away from this mentality that we are victims. Teachers and planners too, need to feel the hurts and pains, they need to show compassion and go through the emotions with students as teachers, otherwise this cycle of trauma will continue. . . . Most importantly, our traditional beliefs in our spirituality need to be revived without [our] being condemned as pagans or heathens.

Another participant added:

Like I’m just starting to be more aware of it now because I’m being more educated about it now. So that’s what, I like to see more happening is that maybe have a class on intergenerational effects because then that would be good for people who want to know more.

Understanding the historical and current context of Aboriginal peoples’ inequities in society is crucial for instructors and program planners. Yet there seems to be some resistance to it, as one student observed:

I don’t think people are as patient when it comes to Aboriginals. Like we see Jewish people in concentration camps and we feel bad for them. And yet . . . you hear comments like, well, they got over it pretty quick. But they were a very highly educated group of people before that happened and it was. . . . 10 years of abuse versus like a hundred years of being put down and, um, not necessarily having a lot of education to begin with. . . . So, you know, we couldn’t just bounce back and all become doctors and lawyers. . . . I just think that there’s a lot more that can be done as far as teaching people why this has happened. Why you can’t just get over it. And why you need to be more sympathetic and help. So instead of, you know, seeing just like a drunken Indian on the street, see that person, like see them as a person and see why they may have ended up there. You know, whether they came to Winnipeg from a reserve to try and have a better life—but when you’re not equipped with an education, it’s hard to find a job. And all of a sudden you kind of get lost in the system and you lose hope.

Students perceived trust as an essential component of human relationships within the educational experience. The effects of intergenerational trauma contribute to students’ experience of a deep mistrust of non-Indigenous people, and a lack of belief that they will find understanding and safety in the classroom. Many of their recommendations indicated a crucial need for action directed toward the building of trust between students, instructors and program planners. Student recommendations for instructors and program planners to manage effects of IGT in class are listed below:

Build trust,

be approachable and use clear language,

reach out by listening and helping to build self-esteem,

provide lecture notes,

note students’ different backgrounds and needs,

note that trauma survivors may need counseling,

connect students with academic and counseling supports,

keep an open mind,

integrate Indigenous beliefs and offer the circle format for class,

acknowledge the reality of IGT and learn about it,

be aware of challenges arising out of moving from reserve to city,

recognize that people may have difficulty coping with new systems,

develop a compassionate view toward the complexity of Aboriginal peoples’ life situations,

stay connected with Aboriginal grassroots situations,

recognize the stigma related to access and Aboriginal-focused programs,

acknowledge resentment toward Aboriginal student funding by both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal students—not all Aboriginal students are funded,

be cautious about singling out Aboriginal students because they may be embarrassed,

realize that students want accessible resources, not special treatment, and

facilitate use of exercise facilities because students may not be able to afford them.

Students did not want to be perceived as receiving special treatment. One elaborated on this point, saying:

I found actually my professors have been very understanding, you know. But I don’t think we should get special treatment or anything. But there definitely needs to be supports in place to help people who’ve gone through this, who are suffering from trauma even years after, you know, to get through it and to build their self-confidence. No, we can stand on our own two feet.

Instructors and planners need to be aware that First Nation students who are funded experience resentment from both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people. Several students reported this dynamic. One student recalled the following:

Once like I was even discriminated, too, because of being Treaty. And my friend wanted to send her boys, they’re older now, they’re going to school now but they’re paying for it, eh. And they said, “Oh that must be nice to have your education handed to you.” Handed? No. Got to ask for that funding. Not every student is funded 100%. And even then you still got to work for your marks. So it’s not handed. Yeah, I said, and then the only way [I am] on treaty is because my mother never married. . . . I says, well, see not being married, that comes with a little label, too.

Students determined to succeed. Students expressed determination to succeed and overcome obstacles in their education, and some expressed strong pride in the accomplishments of their people. In one student’s words,

Because, we, all of us girls, are still fighting. We’re still coming back next year, you know. We’re not going to let these little people beat us down, you know. Like we’re fighting for our future and we’re fighting for our children’s future. And … we came a long way in the last 150 years, you know what I mean. If we can do this much in that amount of time, I say, kudos to us.

The following is a list of student-identified, self-help strategies:

Identifying with traditional culture: spirituality, sweats, smudge, ceremonies;

finding mentors: family, peers, academics;

seeking out elders, counselors, and helpers;

becoming self-aware of needs;

standing up for my rights;

having a center for Aboriginal Health Education;

screaming, a traditional way of healing;

integrating my learning into my healing journey;

taking risks in education;

sharing with others; and

being resilient—life goes on.

Some childhood strategies that had been used helped students minimize problems within their education. One student recalled the following:

There’s a mechanism, right from abuse and stuff, right. So it’s like . . . I don’t remember anything really from my childhood. I can remember small pieces. So that skill has helped me as a university student because I can separate myself from the upheaval. And then cry it off and then OK, now I can do, you know. And being resilient. . . . I can adapt to things, which happens to be what happened in my childhood. I can get to, can be in a different environment, and adapt really quickly because of how I lived.

Administrative staff and instructors’ perceptions of overcoming effects of IGT. When asked what might help students overcome the effects of IGT within education administrative staff and instructors expressed key concepts to consider in the following response:

Part of multigenerational trauma is unresolved grieving. And so, we just, we never really grieve and then we, you know we’re re-traumatized and re-traumatized. I think that grief work is very important, and I don’t think we do enough of it. . . . At a certain point it’s not, it’s not healing, we move beyond healing to wellness.

An Aboriginal respondent added,

The traditional teachings, uh, experiencing, participating in ceremonies, learning about history, . . . our own histories, not just non-Aboriginal Peoples’ version of our histories, all of that is, are aspects of educational strategies that, that will address intergenerational trauma and help students move through it. And stop it.

Several strategies that were noted by staff as helpful to students in overcoming the effects of IGT are listed below:

Counselling and academic advising;

transition-year programs;

basic literacy skills;

research on student success factors;

education on IGT and history for administration, faculty, and students;

mentoring;

traditional teachings and sharing circles;

better resources for off-campus students;

high expectations of students;

addressing “social passing”; and

grief work.

Staff and instructors stressed that the administration has influence it can use to address IGT and its impact on students. Important factors to consider include dedicated space for Aboriginal students; programming that focuses on wellness with life skills training; Elders, academic, and counseling supports; increased awareness of IGT throughout education; and enhanced education for faculty. Hiring more Aboriginal staff means visible role models are available for students. Systems-level recommendations for administrators included developing strategies for effective teamwork, especially sharing information and following through with students, and supporting personnel, instructors, and faculty working with Aboriginal students. Education must be recognized as an essential element in healing and recovery from IGT.

Trauma-informed approach to education is crucial for mitigating the effects of intergenerational trauma. Research supports the suggestion that family instability, adverse childhood experiences, family violence, and substance abuse are prevalent in Aboriginal communities (Bellany & Hardy, 2015; Yellow Horse Brave Heart et al., 2011). These factors were all described as effects of IGT by the student participants. Students experience pressures resulting from these factors in addition to stress related to their schoolwork. It is crucial that the effects of IGT on student performance be understood, and that the reality of accumulative trauma experiences in students’ lives be accepted as truth. Achieving that goal will require taking a trauma-informed approach to education in which all people interacting with students understand IGT and are able to respond from a healing perspective. Duran and Duran (1995, as cited in Menzies, 2007) posited that problems have become part of the heritage due to the decades of forced assimilation. A trauma-informed approach blended with cultural teachings by Indigenous teachers will help students mitigate the effects of IGT and heal—ideally, enough to attain their educational goals (University of Calgary, 2012).

A program intended to build collective teacher capacity to incorporate Aboriginal knowledge, language, and culture into a caring curriculum that considers what is happening in students’ lives was successfully piloted in a Canadian First Nations high school, with encouraging results, including improvements in attendance, decreased discipline incidents, increased credits earned, and higher numbers of graduates from high school (Mombourquette & Head, 2014). These strategies can be adapted to post-secondary education. Students with IGT experiences require appropriate supports to maximize their strengths in their educational journey to continue to heal and be part of a new generation that can contribute to wellness in their communities (Cavanaugh, 2016; McInerney & McKlindon, n.d.; University of Calgary, 2012).

Within the Healing Lodge we contemplate this knowledge and how to use it in our relationships with students and our educational practices and policies.

Final Words

Aboriginal post-secondary students spoke from their hearts about IGT’s effect on their educational journeys. Program instructors and administrators considered strategies to mitigate IGT’s impact on education. An Indigenous framework and worldview guided the study. The study question arose from our concern that students did not complete assignments and subsequently failed courses in which their participation and performance was otherwise satisfactory. Our conversation interviews with participants support the supposition that IGT is a significant factor many Aboriginal students experience in post-secondary studies.

Although the discussion of IGT and its impact on education is in its infancy, study participants agreed that this issue requires recognition in post-secondary education and that education is a component of healing. All identified a need to sensitively engage with material about colonization and the impact of IRS. In efforts to employ improved academic and student support models, trauma-informed education must be implemented to assist students, faculty, and administrators to build trust in interpersonal relationships. Building on the resilience and survival skills of Aboriginal students, educators and post-secondary institutions can create stronger educational responses that foster healing from IGT and, consequently, educational success. Trauma-informed approaches implemented in primary and secondary schools should be used in higher education institutions to assist Indigenous students to manage the historical and intergenerational trauma that impacts their educational experience (Ontario Federation of Indigenous Friendship Center, 2016). Trauma-informed education assists Indigenous students to learn about the effects of colonization on their lives, families, communities, and educational journeys. Non-Indigenous educational workers trained in trauma-informed principles become sensitive to the trauma issues Indigenous students endure.

We urge educators to study the Calls to Action in the 94 Final Recommendations of the TRC (2015) and the United Nations’ (2008) Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. We believe the Calls to Action converge with our study results, and call for more attention and resources that address the root causes of trauma affecting Aboriginal students. Culturally safe, trauma-informed approaches will help to mitigate the impacts of IGT on Aboriginal students in the academy. We believe that listening and responding to the voices of Indigenous students is a step forward in the decolonization of educational systems and will eventually contribute to the development of Indigenous scholars and the Indigenous renaissance identified by Battiste (2013).

References

Battiste, M. (2013). Decolonizing education: Nourishing the learning spirit. Saskatoon, SK: Purich.

Bellamy, S., & Hardy, C. (2015). Post-traumatic stress disorder in Aboriginal people in Canada: Review of risk factors, the current state of knowledge, and future directions. Prince George, BC: National Collaboration Center for Aboriginal Health. Retrieved from https://www.ccnsa-nccah.ca/docs/emerging/RPT-Post-TraumaticStressDisorder-Bellamy-Hardy-EN.pdf

Benton-Banai, E. (1988). The Mishomis book: The voice of the Ojibway. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Bombay, A., Matheson, K., & Anisman, H. (2009). Intergenerational trauma: Convergence of multiple processes among First Nations peoples in Canada. Journal of Aboriginal Health, 5(3), 6 - 47.

Bombay, A., Matheson, K., & Anisman, H. (2014). The intergerational effect of Indian residential schools: Implications for the concept of historical trauma. Transcultural Psychiatry, 5(3), 329 - 338. doi:10.1177/136348153503381

Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission on Residential Schools. (2015). Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Final Report and Recommendations of Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission on Residential Schools. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Retrieved from http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/File/2015/Exec_Summary_2015_06_25_web_o.pdf

Cavanaugh, B. (2016). Trauma-informed classrooms and schools. Beyond Behavior, 25(2), 41-46. doi:10.1177/107429561602500206

Clarkson, L., Morrissette, V., & Regallet, G. (1992). Our responsibility to the seventh generation. International Institute for Sustainable Development. Retrieved from http://www.iisd.org/7thgen/

Elliot, D. E., Bjelajac, P., Fallot, R. D., Markoff, L. S., & Reed, B. G. (2005). Trauma-informed or trauma-denied: Principles and implementation of trauma-informed services for women. Journal of Community Psychology, 33(4), 461 - 477. doi:10.1002/jcop.20063

Four Directions Teachings.com (2006). Ojibwe/Powawatomi (Anishinabe) teaching: Elder Lillian Pitawanakwat. 4D Interactive, Inc. Retrieved from http://www.fourdirectionsteachings.com/transcripts/ojibwe.pdf

Kovach, M. (2010). Conversational methods in Indigenous research. First People Child and Family Review, 5(1), 40 - 48. Retrieved from https://fncaringsociety.com/sites/default/files/online-journal/vol5num1/Kovach_pp40.pdf

Lyons, O. (n.d.). Seven Generations – the Role of Chief. Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/warrior/content/timeline/opendoor/roleOfChief.html

Menzies, P. (2007). Understanding Aboriginal intergeneration trauma from a social work perspective. Canadian Journal of Native Studies, XXVII(2), 367 - 392. Retrieved from http://www3.brandonu.ca/cjns/27.2/05Menzies.pdf

Menzies, P. (2010). Intergenerational trauma from a mental health perspective. Native Social Work Journal, 7(November), 63 - 85. Retrieved from https://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/obj/thesescanada/vol2/OSUL/TC-OSUL-384.PDF

McInerney, M., & McKlindon, A. (n.d.). Unlocking the door to learning: Trauma-informed classrooms & transformational schools. Education Law Center.

Mombourquette, C., & Bruised-Head, A. (2014). Building First Nations capacity through teacher efficacy. The Canadian Journal of Native Studies, 34(2), 105 - 123.

Mordoch, E., & Gaywish, R. (2011). Is there a need for healing in the classroom? Exploring trauma-informed education for aboriginal mature students. in education, 17(3), 96 - 106. Retrieved from http://ineducation.ca/ineducation/article/view/75/559

Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (1996). The posttraumatic growth inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 9(3), 455 - 471.

Ontario Federation of Indigenous Friendship Center (OFFIC). (2016). Trauma informed schools; A study on the shift toward trauma informed practice in schools., OFIFC Research Series, 4(Summer).

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Volume One: Summary: Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future. Toronto, ON: James Lorimer.

United Nations. (2008). Declaration on the rights of Indigenous peoples. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf

University of Calgary (2012, Winter). Intervention to address intergenerational trauma: Overcoming, resisting and preventing structural violence. Retrieved from https://www.ucalgary.ca/wethurston/files/wethurston/Report_InterventionToAddressIntergenerationalTrauma.pdfWilson, S. (2001). What is an Indigenous research methodology? Canadian Journal of Native Education, 25(2), 175 - 179. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/234754037_What_Is_an_Indigenous_Research_Methodology

Yellow Horse Brave Heart, M., Chase, J., Elkins, J., & Altschui, D. (2011). Historical trauma among Indigenous peoples of the Americas: Concepts, research and clinical considerations. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 43(4), 282 - 290. doi:10.4324/9781315751061

Endnotes

1 Recent epigenetic-focused studies examining the cumulative physiological and behavioural effects of trauma support the idea that trauma can be embedded in DNA and transmitted inter-generationally across multiple generations. See Bombay, Matheson & Anisman, 2009, 2014. Yehuda (2018) notes this has not been established in humans. The intergenerational transmission of trauma may also assist the organism to adjust to adverse circumstance p. 252).

2 For details on the Four Lodges approach used in this study, please see Mordoch and Gaywish (2011).

3 Regarding the use of Aboriginal versus Indigenous in this paper, we decided to use Aboriginal in this instance. We did have an issue in the research process where a student who is Indigenous from elsewhere in the world wanted to participate, and we discussed whether to include other Indigenous participants (other than Aboriginal). We decided to limit student participation to Aboriginal Canadian students. Aboriginal is still the legal definition in Canada for First Nation, Métis, and Inuit.

4 See Endnote #1