Insignificant

Stories: The Burden of Feeling Unhinged and Uncanny in Detours of

Teaching, Learning, and Reading

David

Lewkowich

McGill

University

Author

Note

David

Lewkowich, McGill University, Faculty of Education, Department of

Integrated Studies in Education

Correspondence

concerning this article should be addressed to David Lewkowich,

E-mail: david.lewkowich@mail.mcgill.ca

“Words

had always left long bloody marks wherever they fell.”

-Knut

Hamsun, Hunger (1890/2008, p. 120)

I am going to start off this article with a detour (and to be fair, it

is not the only one I will pursue), which I know may seem a strange

place to begin, but sometimes by starting theoretically out of place,

we work our way into the folds of a bloodier space, where the text

leaves its entrails dripping and strewed, readable through its very

vulnerability; a body with its organs exposed is a body that is

literally fuller than full. I am here gesturing to Lacan’s

(1991) cryptic methodological turn, which he took up in his

discussion of Freud’s (1919/2003) concept of the ego; “It

is from this long way off,” he has written, “that

we will start in order to return back towards the centre —which

will bring us back to the long way” (p. 3). The method

of writing I adopt in this article, which explores the psychoanalytic

concept of the uncanny in spaces of teaching and reading, is

therefore one of circuitous reasoning (which obviously resembles a

kind of nonsense), but since the uncanny itself functions to effect a

distortion of memory, circuitousness is certainly an apt path to

follow.

am going to start off this article with a detour (and to be fair, it

is not the only one I will pursue), which I know may seem a strange

place to begin, but sometimes by starting theoretically out of place,

we work our way into the folds of a bloodier space, where the text

leaves its entrails dripping and strewed, readable through its very

vulnerability; a body with its organs exposed is a body that is

literally fuller than full. I am here gesturing to Lacan’s

(1991) cryptic methodological turn, which he took up in his

discussion of Freud’s (1919/2003) concept of the ego; “It

is from this long way off,” he has written, “that

we will start in order to return back towards the centre —which

will bring us back to the long way” (p. 3). The method

of writing I adopt in this article, which explores the psychoanalytic

concept of the uncanny in spaces of teaching and reading, is

therefore one of circuitous reasoning (which obviously resembles a

kind of nonsense), but since the uncanny itself functions to effect a

distortion of memory, circuitousness is certainly an apt path to

follow.

From

passage to passage, I am taking up tangential reasoning in an overall

“embrace of the arbitrary” (Bloomer, 1993, p. 16) and

teasing a measure of significance out of the otherwise insignificant

(Stiegler, 2009); I am also taking seriously Heller-Roazen’s

(2005) claim that “from one language to another, something

always remains, even if no one is left to recall it” (p. 77).

As I read it, this is not a claim that concerns only the vagaries of

memory, or the shifting of language, though it certainly involves the

crossing of such strictures. It is a claim that deals with the world

we inhabit, the ways such inhabitancy is forever ghosted, and the

reminders that strike us in ways unintended, our past lives that

shift through the passage of time.

Through

sometimes-contrasting styles of presentation (which are meant to

disturb and juxtapose, rather than simply confuse), this article

approaches the fields of teaching and reading as inevitably informed

by the movable meanings of memory. Each section of this article can

thus be read as an individual scene, which, taken together, composes

an intricate drama. In defining this endeavour as a partly

autobiographical pursuit,1

I am here interested in the possibilities that emerge in the creation

(and theorization) of what Mitchell, Strong-Wilson, Pithouse, and

Allnutt (2011) have referred to as “remembering spaces,”

and the ways in which such spatial events can serve as imaginative

reminders of the fact that “the spaces we move through are not

neutral” (p. 3). What this lack of neutrality implies is that

these spaces are always socially composed, even when such sociality

is simply the result of being populated by an other that is our

unconscious self (Kristeva, 1991).

In such

“remembering spaces,” it is also worth keeping in mind

that, as Britzman (1998) has succinctly put it, “There is

always more to the story,” which in relation to the “haunting

persistence” of the uncanny, “can be examined only in

bits and pieces” (p. 14). It is with this awareness of the

fragmented influence of the uncanny on spaces of memory that I

suggest a strategy of reading that lets itself stray, and that

requests of the reader an imaginative and collaborative interpretive

practice. Though I describe the psychoanalytic model of the uncanny

at length later on in this article, it is here worth mentioning that

an uncanny experience is one in which the past is unintentionally

repeated, and where, though what emerges may no doubt bear some

unclear resemblance to a past event or encounter, it is also

inevitably distorted. That which is uncanny is, therefore,

simultaneously familiar and foreign; it is this distorted repetition

often causes distress and a feeling of being unhinged.

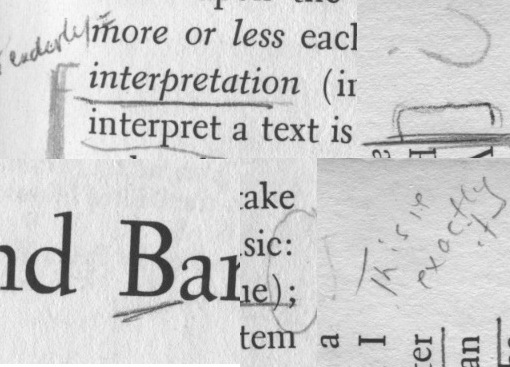

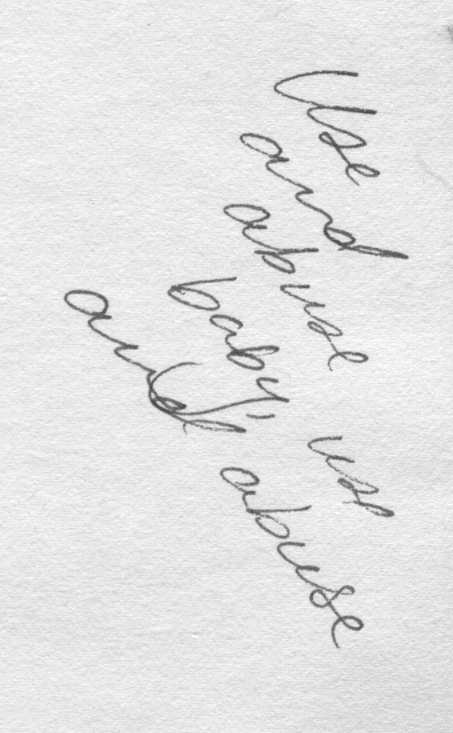

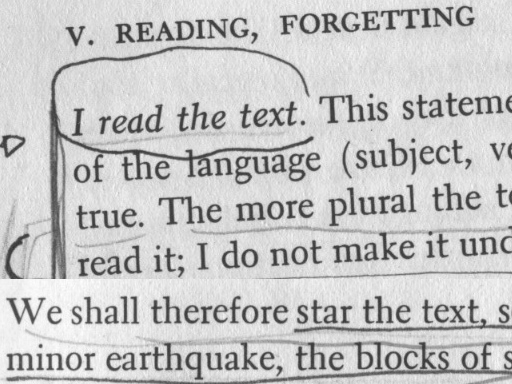

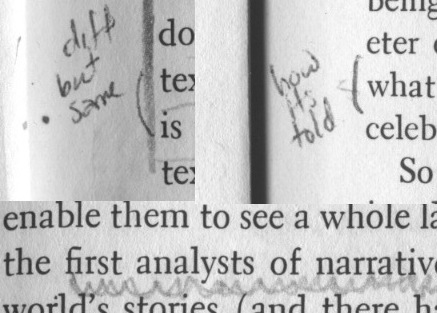

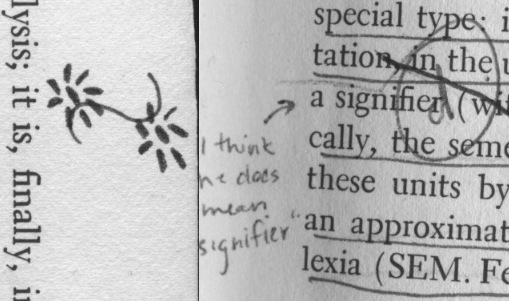

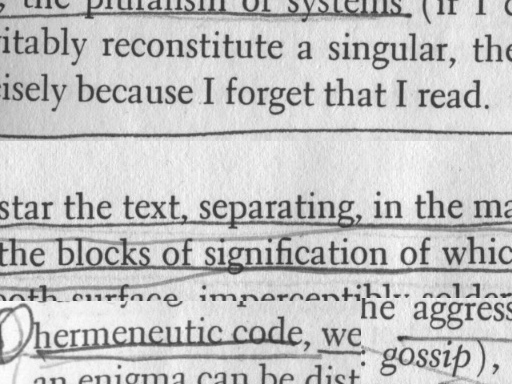

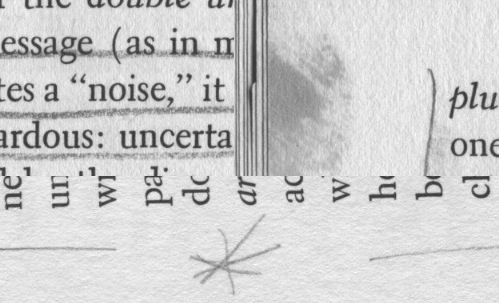

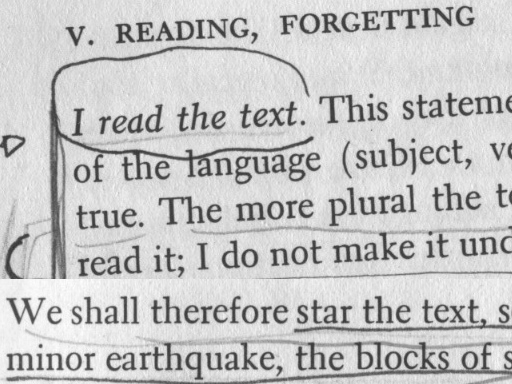

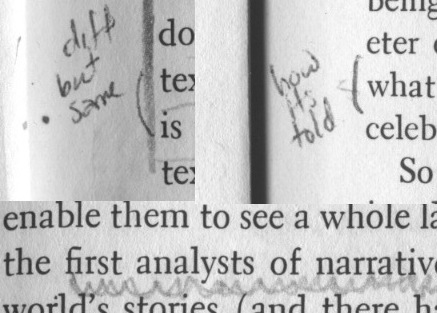

Though

every reading inevitably depends on some degree of collaboration

between the reader and text, this article takes up the challenge of

multimodality described by Gee (2008), wherein words and images mix

to create a scene of inseparable sense that requires “non-linear

ways of reading” (King, 2011, p. 74). Through inserting various

images in this article, and stylizing the text in more than one way,

I am gesturing towards the  potential

uses of guttering in academic writing. As King (2011) has

described this practice of aesthetic presentation in relation to

graphic novels, “the gutters (the spaces between panels) lead

readers to make connections and establish closure” across a

variety of textual forms, which “also allows readers to pause

between panels as they make meaning” (p. 71). The gutters are,

therefore, a form of interpretive interruption. The gutters

themselves may be empty (which like any absence signals a presence),

or they may be inscribed with some textual gesture that stands apart

from—while remaining simultaneously dependent upon—the

main part of the textual frame. The point of such a practice is,

thus, to proliferate the potential for spaces of meaning in

encounters of reading, and to do so in a way that such meaning

remains unresolved and necessarily in tension, which is to say,

always newly interpretable.

potential

uses of guttering in academic writing. As King (2011) has

described this practice of aesthetic presentation in relation to

graphic novels, “the gutters (the spaces between panels) lead

readers to make connections and establish closure” across a

variety of textual forms, which “also allows readers to pause

between panels as they make meaning” (p. 71). The gutters are,

therefore, a form of interpretive interruption. The gutters

themselves may be empty (which like any absence signals a presence),

or they may be inscribed with some textual gesture that stands apart

from—while remaining simultaneously dependent upon—the

main part of the textual frame. The point of such a practice is,

thus, to proliferate the potential for spaces of meaning in

encounters of reading, and to do so in a way that such meaning

remains unresolved and necessarily in tension, which is to say,

always newly interpretable.

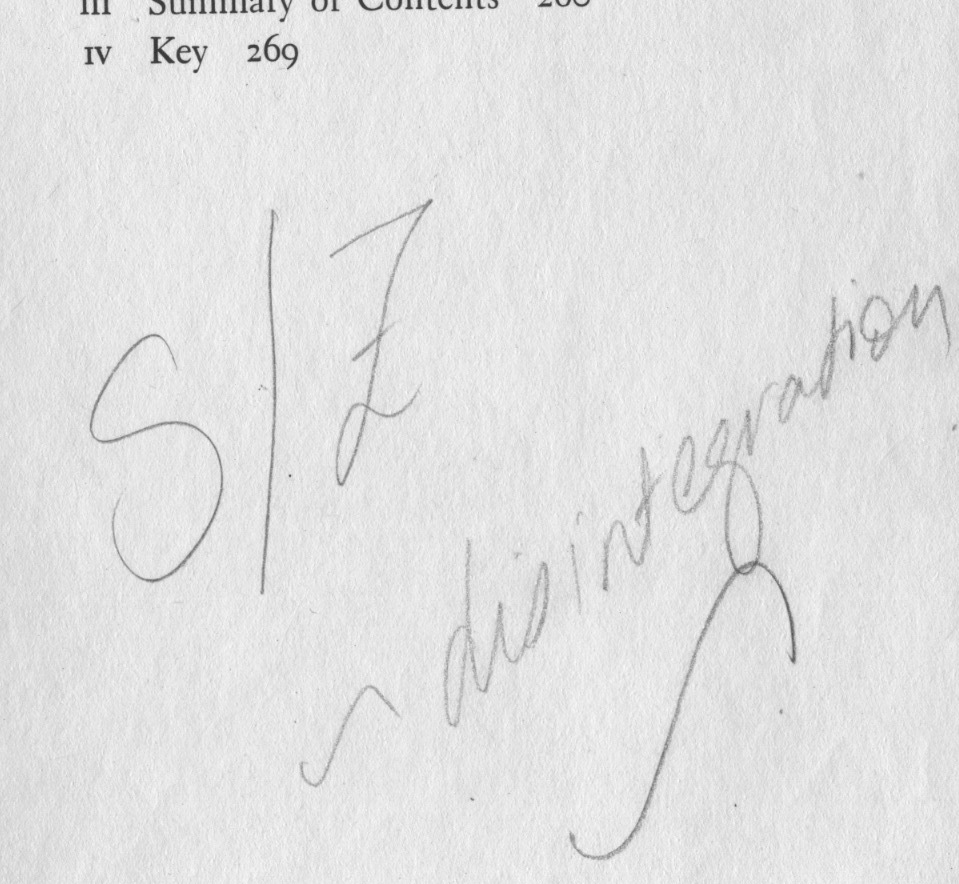

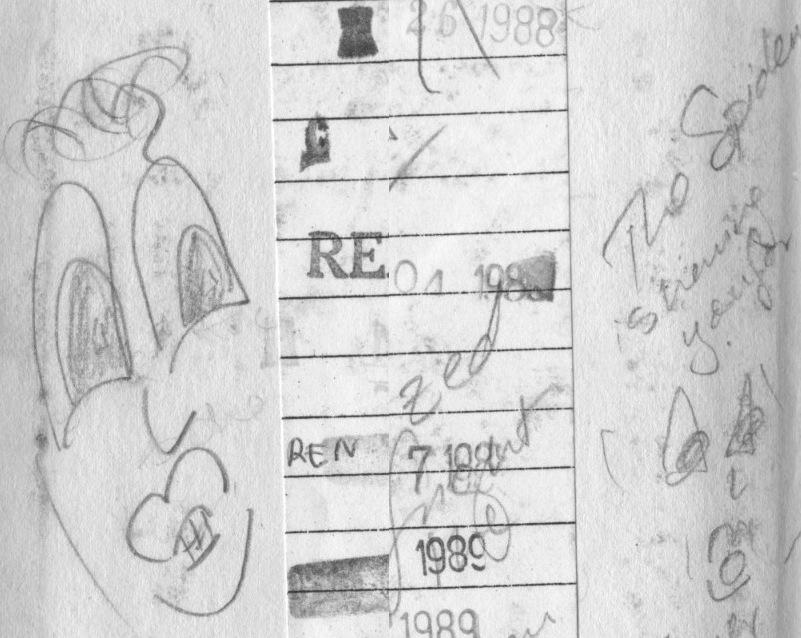

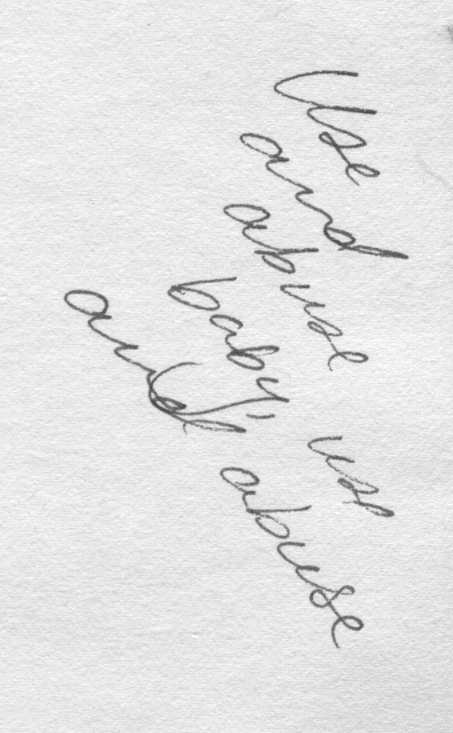

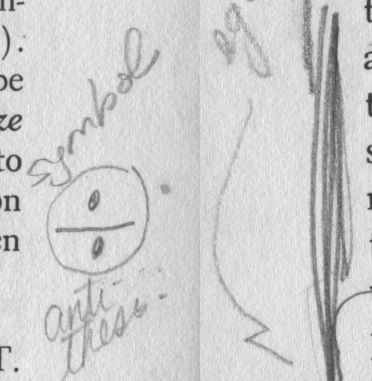

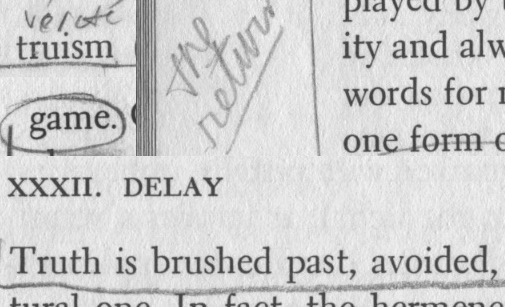

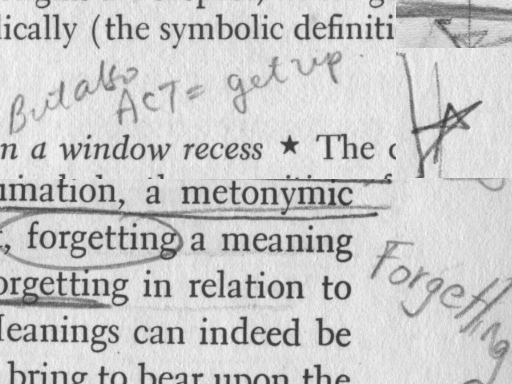

The

images that appear in this article, whose particular origins I

describe later on, were found in the margins of a library copy of

Roland Barthes’ S/Z (1974). In my arrangement of these

images, which may seem admittedly haphazard (some are juxtaposed,

some are not, some are legible, some hardly so), I am taking up the

challenges of learning in the margins (an always unsure

endeavour), described by Irwin and O’Donoghue (2012) in

their discussion of relational aesthetics in teacher education. While

a text might teach one thing, they ask, what does its margins—and

there its traces of past readerships and past desires—teach?

How do these margins provoke an often-unacknowledged uncanniness in

reading experience? As Irwin and O’Donoghue (2012) have

written, when it comes to readers’ responses in encountering

the marginal traces of others, “to some this was disruptive; to

others this was stimulating” (p. 227). Throughout this piece,

I, therefore, use these images as a relational and emotionally

provocative space for marginal thinking, well aware that a reader’s

response can never be predetermined. In the following section, I

begin with a literary scene, through which I take up the question of

emotional burden in relation to social attachments.

Part

1: The Story of a Dog

In Niki,

The Story of a Dog, Hungarian novelist Tibor Déry

(1956/2009) describes the fundamentally vulnerable and emotionally

unstable nature of our intersubjective attachments to others. In this

novel, Niki, a young, spry fox terrier, playfully connives her way

into the lives of Mr. and Mrs. Anksa, who, although fond of animals,

are reticent about allowing themselves to become too familiar with

this particular creature. Because Mr. Anska’s father had only a

short time ago been killed in a saturation air raid, and because the

couple had just recently lost their son in the Battle of Voronezh

during the Second World War, they were initially opposed to the idea

of assuming, what Déry calls, a new burden of feeling,

which can here be described as an affectively persistent encumbrance

that is charged and disposed through human and non-human relations of

meaning, interdependency, and reliance. As the author notes, the

Anksas “had good reason to know that affection is not only a

pleasure for the heart but also a burden which … may oppress

the soul quite as much as it rejoices it” (p. 9). Put simply,

the Anksas were well aware that what might bring them joy today, and

allow them to mourn their recent losses, would also most certainly

bring them a new type of grief tomorrow. It is a fear similar to that

described by Kristeva (1991): “I lose my boundaries, I no

longer have a container, the memory of experiences … overwhelm

me, I lose my composure” (p. 187). As the Anksas discover, in

the presence of others, we cannot help but be emotionally unraveled.

Though

Mr. Anksa tried his best to frighten the dog away—he calls her

a “dirty, clinging, brute” (p. 18)—the Anksas were

powerless under the ferocious influence of Niki’s love, what

Mr. Anksa describes as “the unfair weapon … against

which I have no defense” (p. 20). They tried not to refer to

her by name (as if doing so would be to admit their frailty in the

face of love), calling her only “the bitch,” “the

dog,” “the brute,” or “the terrier,”

but as their affection grew, the Anksas took up this burden of

feeling with a furious passion that knew no negation; they “would

not now have hesitated to spill blood in [her] defense” (p.

86). Despite their initial opposition and resistance, the Anksas

were, thus, mutually outdone and undone by that which, in any case,

they were powerless against from the start. Such a burden of feeling,

though its shape may change, is a weight that we all bear as a

consequence of being in the world and of having a history, and as

with Niki and the Anksas, even if we do not name it, we are

nevertheless forced to carry its load.

Though

the story of the Anksas and their burden may seem far removed from

our present concerns, for those interested in theorizing the psychic

demands of education, such a process of carrying implies, as noted by

Lisa Farley (2009), “the ways in which our educational

histories linger, haunt, and shape the pedagogical present” (p.

18). Even though this burden can seem a ruthless structure under

which we are all powerless subjects, as even the monkey on our back

becomes a gorilla, can we make of it something potentially joyous?

Though we are beasts of emotional burden, can we carry this burden

well?

Part

2: The Teacher as Reader

In this

article, I approach the position of the teacher as a desiring reader:

as interpreter of educational experience, as perambulator through

fields of emotional inheritance. Rather than simply a skill to be

learned, teaching, in this regard, is “a form of memory”

(Farley, 2009, p. 18). There is a burden of feeling that accompanies

every educational act, an overabundance of affect whose spectral

circulations necessarily motivate unconscious movements of love,

hate, authority, and desire. As Adam Phillips (1995) has so bluntly

stated, “We are too much for ourselves … we are …

terrorized by an excess of feeling … an impossibility of

desire” (p. xii). In our efforts to discourage uncertainty

(staging often-disharmonious movements that attempt to pry the

present from the clutches of the past, or looking to the world of the

past as ruptured apart from that of our own), we, as educators,

frequently endeavor to move backwards and forwards in that which can

only be called the chronologically perverse—the muddied

ontological grammar that inevitably represents education’s

precarious plotting—and find ourselves stuck in the middle,

between facing others and meeting ourselves. As Sara Ahmed (2006a)

has noted, however, “this backward glance also means an

openness to the future, as the imperfect translation of what is

behind us” (p. 570). For the teacher, the past carries the

sound that is echoed in the future; and such reverberations, when

they remind us of a thing that we feel we know but still cannot name,

might well be experienced as confusing, hostile, unspeakable,

debilitating, or shattering. By setting foot back in the space of

school, we stage a return that is necessarily uncanny, a strangeness

that is nonetheless known, intimate, and familiar (Britzman, 1998;

Salvio, 2007); we cannot escape its thrall. Through positing the

notion of a burden of feeling, this article theorizes the

psychoanalytic concept of the uncanny as a way to think through the

narrative difficulties inherent in effectively interpreting the

variously psychical and historical influences of our personal

educational experiences. I, thus, intersperse in the pages that

follow a number of my memories of teaching and schooling (and being

schooled), in the hopes of productively framing our understanding of

educational spaces—spaces of reading and interpretation

always—as necessarily unhinged and uncanny.

For

Freud (1919/2003), the uncanny, which in its original German—Das

Unheimliche—translates literally as “the

unhomely,” “belongs to the realm of the frightening, of

what evokes fear and dread” (p. 123), and “goes back to

what was once well known and had long been familiar” (p. 124).

It relates to the home as a place of origin and deep familiarity,

though, through its negative prefix -un, also indicates the movements

and returns of psychical repression; the unknowable nature of an

alien force. The uncanny, in the way that it figures a return of the

repressed, is most upsetting when encountered as a kind of

“unintended repetition” (p. 144) of a past event (or its

emotional content), where that which is re-encountered, in

necessarily distorted form, makes one frightened, regardless of

whether the original encounter was frightening or not. Though

For

Freud (1919/2003), the uncanny, which in its original German—Das

Unheimliche—translates literally as “the

unhomely,” “belongs to the realm of the frightening, of

what evokes fear and dread” (p. 123), and “goes back to

what was once well known and had long been familiar” (p. 124).

It relates to the home as a place of origin and deep familiarity,

though, through its negative prefix -un, also indicates the movements

and returns of psychical repression; the unknowable nature of an

alien force. The uncanny, in the way that it figures a return of the

repressed, is most upsetting when encountered as a kind of

“unintended repetition” (p. 144) of a past event (or its

emotional content), where that which is re-encountered, in

necessarily distorted form, makes one frightened, regardless of

whether the original encounter was frightening or not. Though  the

uncanny moment is always an encounter with memory, since its content

remains disguised, as in a dream, its relation to the original

experience that forms the memory is not always recognizable as such.

It is this sense of mis-recognition that gives the uncanny its eerie

feeling; it wanders as an unknown memory, a lost and forgotten

object, and an abandoned part of one’s self. Love is a common

thing, as is hate, as is vulnerability and frailty in loving

relations. For teachers, the helplessness experienced as a student

reappears in the helplessness experienced in educating others, which

itself reemerges in the helplessness of one’s own students,

whether real or imagined—a haunting cycle of misidentification

that lurks beneath the surface of educational experience.

the

uncanny moment is always an encounter with memory, since its content

remains disguised, as in a dream, its relation to the original

experience that forms the memory is not always recognizable as such.

It is this sense of mis-recognition that gives the uncanny its eerie

feeling; it wanders as an unknown memory, a lost and forgotten

object, and an abandoned part of one’s self. Love is a common

thing, as is hate, as is vulnerability and frailty in loving

relations. For teachers, the helplessness experienced as a student

reappears in the helplessness experienced in educating others, which

itself reemerges in the helplessness of one’s own students,

whether real or imagined—a haunting cycle of misidentification

that lurks beneath the surface of educational experience.

Part

3: Fantasies of Instinct and Beginnings

As a new

teacher, I was often caught between trying to enact a type of

authenticity in the classroom, while also feeling like I had to adopt

definitively authoritative attitudes, which were at odds with who I

believed I was, and with whom I believed I wanted to be. I recall my

first evening of parent-teacher interviews, which came only a couple

weeks after I had been hired. It was like I had hardly a chance to

catch my breath, and as Lawrence-Lightfoot (2003) has noted of such

occasions, though adults may “come together prepared to focus

on the present and the future of the child … they feel

themselves drawn back into their own pasts … haunted by

ancient childhood dramas” (p. 4). Faced with the likely

reemergence of such a drama, I felt thoroughly unprepared, but

trusted that if I kept talking the right words would come, since, if

I wanted to be an effective teacher, I presumed that, above all else,

I had to put faith in the power of my instincts. I thought to treat

things as in sport—“to become smooth and hard as a

pebble” (Kristeva, 1991, p. 6)—and like the pitcher on

the mound who collapses when he thinks too much about the mechanics

of pitching, I would focus instead on trying to stop thinking, on

distracting myself as a cure for thought. I would speak from the hip,

and from the gut, and from the heart, for to do otherwise would feel

untrue, and to feel untrue would feel as a failure. In one moment,

though, I was faint, sweaty; I clutched a desk and excused myself

from the wide-open eyes staring back at me, sitting in their

children’s seats. The weight of this terrible responsibility

came to me now as a sharp blow. I stared at my face in the bathroom

mirror, “archaic senses [awakened] through a burning sensation”

(Kristeva, 1991, p. 4), and I was scared of what I saw. I hated the

clothes I was wearing, the sweat in my pits and palms, and the cut of

my hair. I was running my hands through the cold water, trying to

numb whatever it was that had to be numbed.

T here

is, in the educational encounter, a kaleidoscopic play of past

provocations that twists our presumed notions of the correct

chronology of time, and mangles our understandings of what Edward

Said (1985) has called “the problem of beginnings” (p.

3). For teachers, the idea of coming back to school reminds us of the

menacing ways that, as noted by Britzman (2011), “passing time

… leave[s] behind fossils” (p. 53); the surprising

reappearance of memories, affects, and past relational strategies,

surfacing in the often-unrecognizable guise of

here

is, in the educational encounter, a kaleidoscopic play of past

provocations that twists our presumed notions of the correct

chronology of time, and mangles our understandings of what Edward

Said (1985) has called “the problem of beginnings” (p.

3). For teachers, the idea of coming back to school reminds us of the

menacing ways that, as noted by Britzman (2011), “passing time

… leave[s] behind fossils” (p. 53); the surprising

reappearance of memories, affects, and past relational strategies,

surfacing in the often-unrecognizable guise of  anxieties,

defenses, desires, and wishes. The use of the term fossils is

here metaphorically apt, for fossils never reemerge exactly as they

were, but are invariably altered in texture and form, as

paleontologists burden through layers of dust to extract hidden

kernels of value, to piece together what was once an object in full

that—as memory—has over time since deteriorated. We also

have barely an idea which remnants of today will be the fossils of

tomorrow. Teacher education is, thus, not a beginning; it always

represents a kind of return (Britzman, 2003).

anxieties,

defenses, desires, and wishes. The use of the term fossils is

here metaphorically apt, for fossils never reemerge exactly as they

were, but are invariably altered in texture and form, as

paleontologists burden through layers of dust to extract hidden

kernels of value, to piece together what was once an object in full

that—as memory—has over time since deteriorated. We also

have barely an idea which remnants of today will be the fossils of

tomorrow. Teacher education is, thus, not a beginning; it always

represents a kind of return (Britzman, 2003).

However,

if we acknowledge the potential of such returns as corrupted

homecomings, we can also, as Peter Brooks (1982) has suggested, talk

about returns as “new beginning[s]” (p. 297) as a way to

“replay time, so that it may not be lost,” and as a

narrative practice of self-oscillation that, in reading experience

repeatedly anew, contributes to twist and “pervert [the

strictures of] time” (p. 299). For Farley (2009), such

practices also involve “the possibility of transforming the

received, static past … into a symbolic narrative, in which we

can discover how buried conflicts shape the present” (p. 20),

and in using our shadows of schooling past, talk out such fossilized

conflicts through a pedagogy whose itching must surely be

scratched—and whose meaning necessarily “resides in the

tensions between the past and the present” (p. 23). It is in

replaying our past, and in searching for uncanny and disturbing

presences (whether they were felt so then or now, and regardless of

whether we can name their origins), that we can signal the ways that

the emotional scripts of the past persist in the present.

Part

4: Passionate Companions

The

lunchroom is one of those spaces where authority is fragile,

precarious, and always susceptible to being hijacked. For the teacher

who administers detention in this room after school, there is a

strangeness that emerges when spaces like this are used to such

contrary ends: eating and discipline, frolic and silence, and

friendship and alienation. Since my own memories of lunchrooms are

food fights and hot dogs, giggles and gropes, and sizing up fashion

and secretive cigarettes, I know well that for encounters in this

awkward zone, every word that is spoken implicitly suggests its

other, as every action is also a challenge to itself. Things are out

of control.

While

supervising afterschool detention, I heard a whistle at one end of

the cafeteria, followed its tune, then a few seconds later heard

another; back where I started so I moved back again. These w ere

confusing tones, for while whistles may be shrill and severe, they

are also seductive and flirtatious. The whistles continued, and when

chasing such whistles, I felt like an animal chasing its tail,

friskily sweeping itself back and forth, taunting and mocking,

provoking and teasing, always just slightly out of reach. The most

disorienting thing about this odd situation was the question of who

was actually doing the chasing; and if I was the dog and the students

my tail, I wanted no less than to chomp down hard. For Kristeva

(1991), “strange is the experience of the abyss separating me

from the other who shocks me—I do not even perceive him,

perhaps he crushes me because I negate him” (p. 187). In the

present case, it was difficult to tell who, in fact, was being

punished; the students, for acting out against school regulations, or

me, in feeling myself to be psychically out of step from, yet also

strangely attracted to, the authoritatively inclined demands of my

profession. I eventually grew bored, and soon, so did the students,

yet I still felt the urge to button their mouths. Unable to connect

my desires in teaching with this urge towards hate and this futile

chase, I was awkwardly moved and unsettled; not knowing whether to

laugh at myself, to tremble in fear, or to froth at the mouth and to

rage against others, smashing my fists into walls.

ere

confusing tones, for while whistles may be shrill and severe, they

are also seductive and flirtatious. The whistles continued, and when

chasing such whistles, I felt like an animal chasing its tail,

friskily sweeping itself back and forth, taunting and mocking,

provoking and teasing, always just slightly out of reach. The most

disorienting thing about this odd situation was the question of who

was actually doing the chasing; and if I was the dog and the students

my tail, I wanted no less than to chomp down hard. For Kristeva

(1991), “strange is the experience of the abyss separating me

from the other who shocks me—I do not even perceive him,

perhaps he crushes me because I negate him” (p. 187). In the

present case, it was difficult to tell who, in fact, was being

punished; the students, for acting out against school regulations, or

me, in feeling myself to be psychically out of step from, yet also

strangely attracted to, the authoritatively inclined demands of my

profession. I eventually grew bored, and soon, so did the students,

yet I still felt the urge to button their mouths. Unable to connect

my desires in teaching with this urge towards hate and this futile

chase, I was awkwardly moved and unsettled; not knowing whether to

laugh at myself, to tremble in fear, or to froth at the mouth and to

rage against others, smashing my fists into walls.

This

short and slippery, almost-trivial scene suggests, as Farley (2009)

has explained, that there is “something elusive, and unspoken,

about history and its passage through the generations” (p. 17);

or, to sound a more perilous illustration from Michael Taussig’s

(1992) reflections on commonplace terror, which point to the ways

that banal communications can oftentimes breach their own limits of

address:

I

am referring to a state of doubleness of social being in which one

moves in bursts between somehow accepting the situation as normal,

only to be thrown into a panic or shocked into disorientation by an

event, a rumor, a sight, something said, or not said—something

that even while it requires the normal in order to make its impact,

destroys it. (p. 18)

While

Michael O’Loughlin (2009) has written that his childhood “is

irretrievably gone,” he has also described how, “My

childhood is not a historical remnant. It is very much who I am

today. I live my childhood anew each day” (p. 81). What we have

here, in O’Loughlin’s (2009) description of “inner

losses … [as] perpetual companions” (p. 100), is a

purposely contradictory understanding of psychic experience, where

“the personal is already a plural condition” (Salvio,

2007, p. 4), and which allows for the fact that even though something

inside of us may be forgotten, it nevertheless refuses to disappear.

It has, in effect, been displaced, through what Paula Salvio (2007)

has beautifully termed “a kind of melancholia that must inhabit

an obscure threshold between memory and forgetting” (p. 13). It

is when we are brushed brusquely against this threshold that the

uncanny emerges in our very self, at the moment that we also witness

its undeniably outside appearance; like some kind of passionate,

demonic double, moving forever further as we chase it away, remaining

always outside our grasp.

Part

5: Teaching as Affected Reading

Judith

Robertson (1994) has spoken of “‘the uncanny moment’

in research,” as “a moment when [a researcher’s]

own history seem[s] somehow to repeat itself” (p. 55).

“Sometimes,” she noted, “I was not sure where I

stopped and where the women [I was interviewing] began”

(Robertson, 1994, p. 55). As previously stated, the uncanny moment is

an encounter with memory whose content remains disguised, so that its

relation to the original experience is not immediately identifiable

or obvious. While the moments where such feelings arise—say, in

the middle of reading a book or teaching a class—might feel

strange, the actual relation of the present experience to the hidden

memory remains elusive, and it is this elusiveness that gives the

experience its quality of strangeness.

As I

write this piece, I am serving as one of 12 jurors on a double murder

trial, and I often find myself theorizing our interpretative

activities as an ideal, possibly an atypical example of the practice

of collaborative reading (though the stakes of our interpretive moves

are admittedly severe). There are times, though, when I catch myself

out, and which feel like a moment of (mis)recognition, where I see

that my theorizing is really an attempt to evade the brutal fact of

the place in which I am. I can likewise affirm that my life as a

child, as an adolescent, and as a student learning to teach, persists

in the various anxieties and pleasures I continue to experience as an

educator, and which are also often projected onto the actions I read

into those who surround me. To talk about a theory of reading in

relation to teacher education must also be to admit the fact that,

due to our insistent burdens of feeling, readings are always

necessarily unstable and multiply mediated: “That every act of

interpretation involves the person who is making that interpretation

bringing their own emotional [histories] into the equation”

(Thurschwell, 2009, p. 39). “When we read,” Thurschwell

(2009) has noted, “the text affects us; our readings affect the

text” (p. 122). The consequences of becoming a teacher are thus

confused by the fact that the life of a student is never really

finished, and though it folds into that of a teacher, the crease is a

muddled space that is hardly discrete. This life of the student is

not simply a memorable force I can figure and touch and use in my

process of coming to know. The moments it contains are also

forgotten, tattered remnants “beneath the façade of

knowing” (O’Loughlin, 2009, p. 80); repressed images and

figures; feelings and vibrations; love and hate that made no sense,

and still they do not.

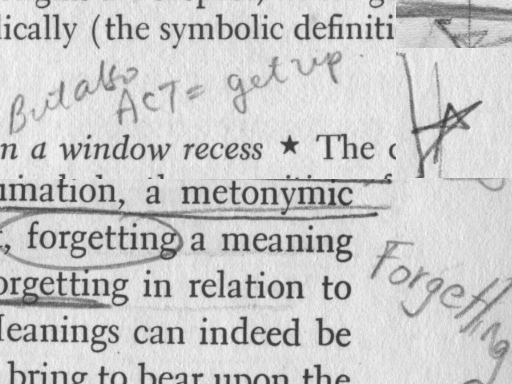

While

writing this article, I am also in the midst of my doctoral research,

which looks at the experiences of adolescents and preservice teachers

in their readings of young adult lit erature.

Because part of this research is in a Montreal-area public high

school where I also sometimes work as a substitute teacher, I have

often had to negotiate the fact that as my responsibilities

change—from student, to researcher, to teacher, and back—it

is not always obvious where exactly I am at, or in what capacity I am

presently assembled. While working as a sub, I recently found myself

in the position of being paired with a teacher that I had never met

before, and though I briefly explained my situation, he somehow took

my description to mean that I was a student teacher. Though I let

this innocuous assumption slide, because the uncanny is our burden of

feeling in teaching and teacher education, this designation provoked

my thoughts to linger in a type of familiar disquiet, which

shockingly recalled how the title of student teacher can be

coupled with the assumption that one is not real, that one is

defined through lack, that one has yet to become an authentic

educator. Though the unsure footing of learning to teach was a place

I had been to before, since I thought I had already passed through

its peculiarities for good, I was made to feel especially strange.

Yet, once again and despite my best wishes, I found myself there; the

burden remained and I felt out of place. I had been there before, and

whatever it was, it was such a weird place my unconscious was saying,

“This is not your home! Get home! Now!” The terrible

truth, however, is not that there is a voice that is screaming that

has no body (and indeed, no scream)—for such uneasiness is not

uncommon—but that this seemingly brutal voicing points to a

home that does not exist, and to which, as to a figment, one can

never return.

erature.

Because part of this research is in a Montreal-area public high

school where I also sometimes work as a substitute teacher, I have

often had to negotiate the fact that as my responsibilities

change—from student, to researcher, to teacher, and back—it

is not always obvious where exactly I am at, or in what capacity I am

presently assembled. While working as a sub, I recently found myself

in the position of being paired with a teacher that I had never met

before, and though I briefly explained my situation, he somehow took

my description to mean that I was a student teacher. Though I let

this innocuous assumption slide, because the uncanny is our burden of

feeling in teaching and teacher education, this designation provoked

my thoughts to linger in a type of familiar disquiet, which

shockingly recalled how the title of student teacher can be

coupled with the assumption that one is not real, that one is

defined through lack, that one has yet to become an authentic

educator. Though the unsure footing of learning to teach was a place

I had been to before, since I thought I had already passed through

its peculiarities for good, I was made to feel especially strange.

Yet, once again and despite my best wishes, I found myself there; the

burden remained and I felt out of place. I had been there before, and

whatever it was, it was such a weird place my unconscious was saying,

“This is not your home! Get home! Now!” The terrible

truth, however, is not that there is a voice that is screaming that

has no body (and indeed, no scream)—for such uneasiness is not

uncommon—but that this seemingly brutal voicing points to a

home that does not exist, and to which, as to a figment, one can

never return.

Part

6: When Unanswered Challenges Come Stumbling Home

In

relation to the way the uncanny insinuates a division of the

threatened subject, Freud (1919/2003) has described how the

convictions and beliefs of our “primitive forebears”—though

we may no longer accept their claims to reality, believing them

successfully surmounted—remain in their nature as unanswered

challenges to newer, contemporary beliefs. Thus, “as soon as

something happens in our lives that seems to confirm these

old, discarded beliefs, we experience a sense of the uncanny”

(p. 154), as these primitive beliefs vie once again for confirmation

and cultural acceptance. In relation to teacher education, such

primitive beliefs can be seen, for example, in practices of corporal

punishment, and in cultural myths that position the teacher as

omnipotent knower, sexless intellect, and unwavering pedagogical

enthusiast. As such myths work to place the failure of any pedagogy

squarely on the shoulders of the teacher, that everything depends

on the teacher (Britzman, 2003), their uncanny appearance

approaches most abruptly in moments of educational breakdown—when

teachers, no matter how well-intentioned, resist the implications of

their student’s claims to a knowledge that is different from

their own; exasperated, react over-defensively to challenges to their

authority; become intolerant to cultural difference; or when, as in

my memory above, the idea of a teacher identity appears yet again as

menacingly unattainable, the impossible desire for an impossible

double.

In

relation to the way the uncanny insinuates a division of the

threatened subject, Freud (1919/2003) has described how the

convictions and beliefs of our “primitive forebears”—though

we may no longer accept their claims to reality, believing them

successfully surmounted—remain in their nature as unanswered

challenges to newer, contemporary beliefs. Thus, “as soon as

something happens in our lives that seems to confirm these

old, discarded beliefs, we experience a sense of the uncanny”

(p. 154), as these primitive beliefs vie once again for confirmation

and cultural acceptance. In relation to teacher education, such

primitive beliefs can be seen, for example, in practices of corporal

punishment, and in cultural myths that position the teacher as

omnipotent knower, sexless intellect, and unwavering pedagogical

enthusiast. As such myths work to place the failure of any pedagogy

squarely on the shoulders of the teacher, that everything depends

on the teacher (Britzman, 2003), their uncanny appearance

approaches most abruptly in moments of educational breakdown—when

teachers, no matter how well-intentioned, resist the implications of

their student’s claims to a knowledge that is different from

their own; exasperated, react over-defensively to challenges to their

authority; become intolerant to cultural difference; or when, as in

my memory above, the idea of a teacher identity appears yet again as

menacingly unattainable, the impossible desire for an impossible

double.

Such

arrivals, which are also always a kind of return, testify to the fact

that the burden of feeling in teaching, learning, and teacher

education is a species of emotional excess that is constantly seeking

a way home. Though it is also an “impossible strangeness”

(Robertson, 2001, p. 205) that stubbornly eludes all capture and

disintegration, “while it may elude consciousness,” as

Salvio (2007) has written, “it longs to return, to make its way

back” (p. 12), but to a location that can no longer be

accessed. No matter how experienced the teacher, there is always a

chance that insecurities will erupt. However, this is not to suggest

that we educators must constantly live in a state of debilitating

fear, and even though this burden of feeling remains as a vestibule,

always on the verge of conscious life, and persists as a state of

emergency, such is the case for all our existence. At any given

moment—in any situation whatsoever—we may become unhinged

and unraveled, moved by the other, intimidated by ourselves as by a

stranger, as “the normality of the abnormal is shown for what

it is” (Taussig, 1992, p. 18). The critical question, as with

the story of Niki and the Anksas, is how we choose to name our

insecurities, and thus, how we choose to read our attachments to

others, while narrating the text of our lived experience.

Importantly, however, it must be kept in mind that naming is not

surmounting, nor is surmounting a practical objective. Though

teaching is here thought as memory, the teacher as reader must take

towards memory an approach that makes memory strange. If teachers are

to consider themselves as readers of education’s emotional

variables, it is important to know what it is that we are reading,

and how to go about life without ignoring the text, unstable as it

may be.

In the

following section, I stage the interview as a site of potentially

uncanny and dis(en)abling irruption; the mind wanders, not always

knowing where it goes, for the wish to stay focused—absolutely

absorbed—necessarily remains unattained. We never read every

word in a book. We can nod, sigh, laugh, or smile, but we never hear

every word that is spoken. Such moments are hard and odd to relate,

because it is unclear what position they actually represent—whether

an ease, an unease, or a dis-ease—and whether what they do is

allow or shut down new forms of insight. These following segments of

interview data, which emerged from my dissertation research, were

undertaken with senior-level students in a Montreal-area public high

school, and revolved around questions of adolescence, schooling, and

reading. In the left column, I have placed certain wanderings of the

mind—the insignificants of interviewing—along with some

thoughts about the meanings such wanderings might hold; on the right

is the speech I am there to absorb, to critique, and to capture in

full. The spaces between, the gutters, the insignificant gaps, are

where I like to return to pose questions of the as-if interview: How

to read as-if one was not there? How to read as-if one was there in

full attention? Though the structure I employ in this section may

strike the reader as unexpected, such surprise also begs the question

of why the expected, in reading experience, is positioned as such.

What do we expect from the expected? In relation to the dynamics of

the qualitative interview, this question speaks to the fact that if

we are only looking for what we expect, we may be blinded to the

unexpected.

|

Part

7: Erroring

It

is a strange thing, interviewing in spaces of schooling. Animated

voices (quivering, exploding) reverberate down hallways and

classrooms, empty shells with Nystrom relief maps, hardened gum on

the desk’s underside, unsharpened pencils and slants of

sunlight. Awkward positioning; myself as interviewer, as reader.

As I ask a question, I am alarmed by the ghoulish shrieks in the

corridor, whistling and yelling, banging and running. The answers

remind me, I have been here before. The answers are set right

across from these words, tattered and scattered and thrown all

around.

Our

words are never our own / Our owned are never in words / We seep /

Like air balloon rips / Like punctured bike tires / The blood is

strip strewn / Like crab cooking screams / We breathe / And

anthills are endlessly stepped on / Our language is like a machine

/ It breaks / Off into pieces / And puddles and poodles / And

laughing hyenas and / Tiptoeing birds / That cackle cacophony /

Coughing up words / And stringing the sentences / Stretched like a

verb / Our words have a life / They are done, dead already

Along

with Norman Klein (1997), who was writing in a much different

context, “I look for ruptures more than coherence. I don’t

mind if the scenes fail to match, or the effects are uneven”

(p. 9). These are shutters, stutters and gestures to meaning. The

interpretation looks to desire. These words, of others and mine

(both absent and present, present though absent), are engulfed in

layers of transition and conversation, and in this movement “I

like to sense the scars, perhaps where a cut was made—objects

removed during the chain of production, at different stages of

participation” (Klein, p. 9). I ask for an offering. A

movement towards. “The final version for me is only the

survivor” (Klein, p. 9). There is so much lost in a

transcribed text.

When

interviewing, I sometimes lose all sense of awareness, and

unexpectedly, my perception seems queerly clouded, like “a

secret wound … wandering” (Kristeva, 1991, p. 5). I

am not sure what is happening, but learn to align myself with the

words until I feel settled again. It is not a feeling of anxiety,

but of slippage. There is a sense that I am weaving in and out of

the present, and time itself feels somehow skewed. It is a

dreamlike, reverie logic, similar to what her been described by

Jane Gallop (2011) as “the logic of ghosts, the temporality

of ghosts,” which “allows something to be both

persistent and vanishing” (p. 137). In these times I feel as

a reader (A bad reader? An inattentive reader? A perverse

reader?); moving on the page, yet moving past the page always. It

is an uncanny reading that cannot be mapped — for de Certeau

(1984), “the map cuts up” (p. 129) — and whose

illegibility “evades textual archaeology” (Moller,

1991, p. 112). It is an uncanny reading that refuses to fasten,

refuses to slacken. There is, in these fugitive moments, an

“impossibility of establishing a clear distinction between

the real and imaginary world” (p. 138). Though to be in such

a place can be frightening, if we wonder, along with Phelan

(1997), “why we long to hold bodies that are gone” (p.

3), such moments are also a reminder that we are never complete in

ourselves, and that our bodies are always, to some extent, gone

and shattered already. No body can “escape the time of its

transience” (Heller-Roazen, 2005, p. 45). Kristeva has

described this experience well: “I feel ‘lost,’

‘indistinct,’ ‘hazy.’ The uncanny

strangeness allows for many variations: they all repeat the

difficulty I have in situating myself with respect to the other”

(p. 187). This feeling is akin to encountering a demon dressed up

in disguise — wearing your face, wearing your body, wearing

your clothes, wearing your smile. It is only on closer inspection

that we come to realize such shattering as an imperfect

reflection, a mirrored self that demands battle. “The other

is my unconscious” (Kristeva, p. 183).

As

words mingle in speech, as we try to make them express what is

always inexpressible, the path language takes is that of desire,

and like all desires, its path is never straightforward, but

follows what we may call a queer route. Within the matrix of a

queer phenomenology—where there is much talk of lines,

inheritances, tendencies, appearances, disappearances, shapings,

slantings, straightenings, queerings, tracings, becomings, and

facings—Sara Ahmed (2006a) has proposed that we challenge

ourselves to revel, to “have joy” (p. 569), in effects

of the uncanny where the familiar turns strange, to “find

hope in what goes astray” (p. 570). In such straying and

errant movement, Ahmed imagines every landscape as potentially

queer; and in characterizing queer as that which is not straight,

she references the concept of desire lines from theories of

landscape architecture, which is “used to describe

unofficial paths, those marks left on the ground that show

everyday comings and going, where people deviate from the paths

they are supposed to follow” (Ahmed, p. 570). In the ways

that such tracings, such lines of rubbed ground, “cut across

the formal grid … risking disappointment and destruction”

(Hall, 2007, p. 287), there are desire lines in speech and writing

as well, which echo unintended meanings, graspings, and pursuals.

What do we risk when we speak a word? There is a hunting that is

happening whenever we talk; there is a motion, a motive, and a

movement. Though its ephemeral nature often relegates such lines

to a zone of exclusion, an area of error, I here want to conjure

up what we might call a method an erroring: to dwell in “the

space between the planned and the providential, the engineered and

the ‘lived’, and between official projects of capture

and containment and … energies which subvert, bypass,

supersede and evade them” (Shepherd & Murray, 2007, p.

1).

As

Ahmed (2004) has suggested, it is possible for pedagogical

spaces—spaces of teaching, learning, and reading—to

engage our capacity for wonder, to intentionally inhabit an unsure

footedness in the face of unintended consequences and error.

Wonder provides a space to compose impossible, ‘as-if’

questions. To read, ‘as-if’ you’ve never read

before. To teach, ‘as-if’ you have no idea what you’re

teaching. To walk, ‘as-if’ your body is broken, or

you’ve come now new to it. To question, ‘as-if’

the answer could be anything in the world. For the space of the

‘as-if,’ things are startling and sudden. As a gesture

towards such potential, these present columns of disparate writing

allow for our readings to linger, and perform associations

unintended between my own words and the transcribed words of

others—cut-up, spliced and diced, these words form a

strange, uncanny, and unruly architecture, through which we can

read as a humbling walk.

|

I have no idea. I

don’t know.

I don’t know.

I’ll figure that out.

I guess it’s

challenging, ‘cause you’re going through things, but I

mean, it’s like anything else. Like, if you’re

middle-aged, you’re going through things, if you’re

elderly, you’re going through things, if you’re a

child, you’re going through things, you know? I think it’s

just a pivotal time in your life, I guess, and yeah, I wouldn’t

say that there’d be one thing to describe it, I guess,

‘cause it’s so varied, depending on who you are, as a

person. I don’t know, it can be hard at times, I guess, but

it’s intense, if anything, ‘cause like everything is

at extremes, I guess, like if you’re very happy you’re

really, really happy. If you’re stressed, you’re very

stressed. If you’re having a hard time at home, you’re

having a really hard time at home. Everything’s kind of in

extremes.

I don’t think

I’m a typical high school student or teenager. I find that

most, I don’t know, I find that most, like other teenagers …

they’re more rebellious than I am … like they’ll

party, and stuff like that.

Complicated, if

anything.

People stealing each

other’s friends, and fights about boyfriends, and it’s

just like … it’s childish, a little bit, and I know

that it happens to everyone, I guess, like I’ve gotten into

fights with my friends, it’s just, I don’t know, I

think you just have to take a step back sometimes, and be like,

‘Really? Is this really what we’re fighting about?

Like, we’re really fighting about who’s wearing that

shirt? Like, seriously? Is that really, in the grand scheme of

things, is that what’s really gonna matter to you?’

Because the way I read

books is, like, each page I read I picture it as if it were a

moment in my life, so I can’t actually draw it down for you,

but I can say that I use my brain, it’s like out in the

open, so I’m absorbing what I’m reading, but I’m

also applying it to my own personal experience, as I’m

reading.

Trust is a big thing

in high school. Nobody has it for one another, like I have very,

very few people that I truly trust. Same thing with teachers,

administration, your parents. You don’t want to trust

anybody, because you feel like you’re kind of isolated,

alone, and you tell one person one thing, and before the day is

over, the whole school knows. And why would you want that?

I don’t like

happy. Like, it has to be really, really depressing, and then

happy. That’s the kind of stuff … it has to be a huge

transition in their life, for me to actually enjoy it. There has

to be a lot of ups and downs, too.

I was never really an

emotional person. But I have a friend who’s like super

unstable with her emotions, and when she was younger, maybe in

grade nine, she was everywhere. She’d be hysterical if

something bad would happen, she would go up the stairs and she

would cry, and you just, you don’t know how to contain

everything that’s going on in your head, and you feel like

everything is so overwhelming, and that, kind of, stuff just piles

on. Like, your parents are being assholes, assholes, or like, your

school, like, the load is too much, and like, there’s like

stuff going on with your friends, so it piles up, and everything

is so dramatic and chaotic in your head, that you don’t know

how to handle anything, so you kind of just, like you overreact,

and do stuff you shouldn’t be doing, just like …

because you don’t know what’s going on, and everything

is so confusing.

They really want to

shove it down our throats.

I don’t think

you’re supposed to ever find yourself in life, and everyone

talks about, ‘When I’m older, I’ll find myself.’

… People are in a constant state of change, and your

personalities are kind of, I guess, malleable. I don’t

believe that people really are a constant, exactly.

They flow into one

another, I guess.

Teachers. Oh, that’s

a good one … They’re either wonderful or they’re

terrible.

I was like so

confused, I didn’t know where to go, I was tiny, I was half

the size I am now, I was just wandering around the school and

didn’t know what to do.

I have to say, school

is kind of killing education.

My mom, she doesn’t

understand why I read these types of books. I don’t know,

she says she finds them kind of useless, ‘cause they’re

kind of girly, and a lot of times it’s like fantasy, and a

lot of that stuff doesn’t really happen, in real life, so

she doesn’t really understand, but …

And also, it’s

the words. I see numbers and they just go all over the place. …

But I see words, and it’s fluid, it’s what makes sense

to me. So I guess it’s my language. It works.

I feel like I look at

these kids, and I’m like, I really hope I wasn’t like

that in grade seven, ‘cause you’re so loud, and you’re

running and you’re like, “I don’t know why you

think this is okay,” but then I kind of have like little

flashbacks of when I was younger, and like … I totally did

that. ‘Cause you’re carefree, you don’t care

what people think about you. That’s one of the good things

about being a younger teenager, is you don’t give a shit

what people think about you, but then as you get older, you’re

more aware of your surroundings, and like … what people

might think of you, or how you’re perceived. That kind of

sucks. So when you’re younger, it’s better …

than when you’re older.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Part

8: Echoed in the Margins

Th ough—as

mentioned above—de Certeau (1984) has asserted that “the

map cuts up,” he also noted that “the story cuts across”

(p. 129), which signals the manner in which methods of textual

architecture and practices of textual space can function to enable,

or dis-enable, the sounding and resonance of particular

narratives and interpretations. There is a constant play of emotional

energies in reading experience, which invariably produces the text as

an ambivalent site, and where it functions as a vessel, whose

doubled meanings have been described by Bloomer (1993) as “both

a container and a conduit, the sea and the ship. It is the thing

disseminated and the instrument of dissemination. Vessels are

instruments in flux: through them flow information, oxygen, food,

antibodies, semen” (p. 95). It is to these imprecise,

epistemologically embodied movements of reader engagement that I now

turn, and which can here be thought of in relation to the Kristevan

semiotic — where “all is flux and incoherence,

provisional, inchoate, occasional” (Ives, 1998, p. 97) —

but which also always persists within and through the boundaries of

the symbolic, which in our present case refers to the stolid logic

enmeshed in the material text. Such binaries intersect and

interweave, signaling the fact that they are actually not binaries at

all.

ough—as

mentioned above—de Certeau (1984) has asserted that “the

map cuts up,” he also noted that “the story cuts across”

(p. 129), which signals the manner in which methods of textual

architecture and practices of textual space can function to enable,

or dis-enable, the sounding and resonance of particular

narratives and interpretations. There is a constant play of emotional

energies in reading experience, which invariably produces the text as

an ambivalent site, and where it functions as a vessel, whose

doubled meanings have been described by Bloomer (1993) as “both

a container and a conduit, the sea and the ship. It is the thing

disseminated and the instrument of dissemination. Vessels are

instruments in flux: through them flow information, oxygen, food,

antibodies, semen” (p. 95). It is to these imprecise,

epistemologically embodied movements of reader engagement that I now

turn, and which can here be thought of in relation to the Kristevan

semiotic — where “all is flux and incoherence,

provisional, inchoate, occasional” (Ives, 1998, p. 97) —

but which also always persists within and through the boundaries of

the symbolic, which in our present case refers to the stolid logic

enmeshed in the material text. Such binaries intersect and

interweave, signaling the fact that they are actually not binaries at

all.

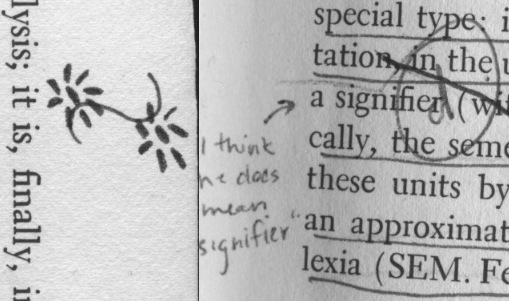

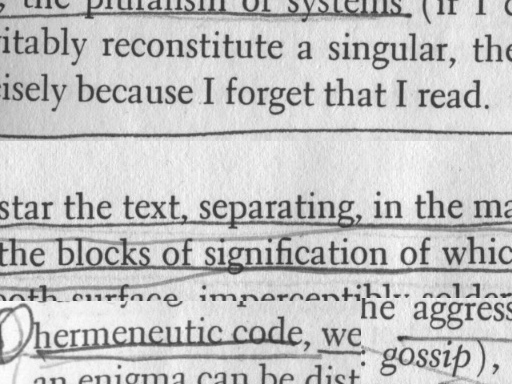

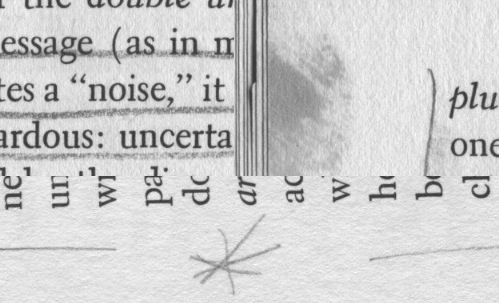

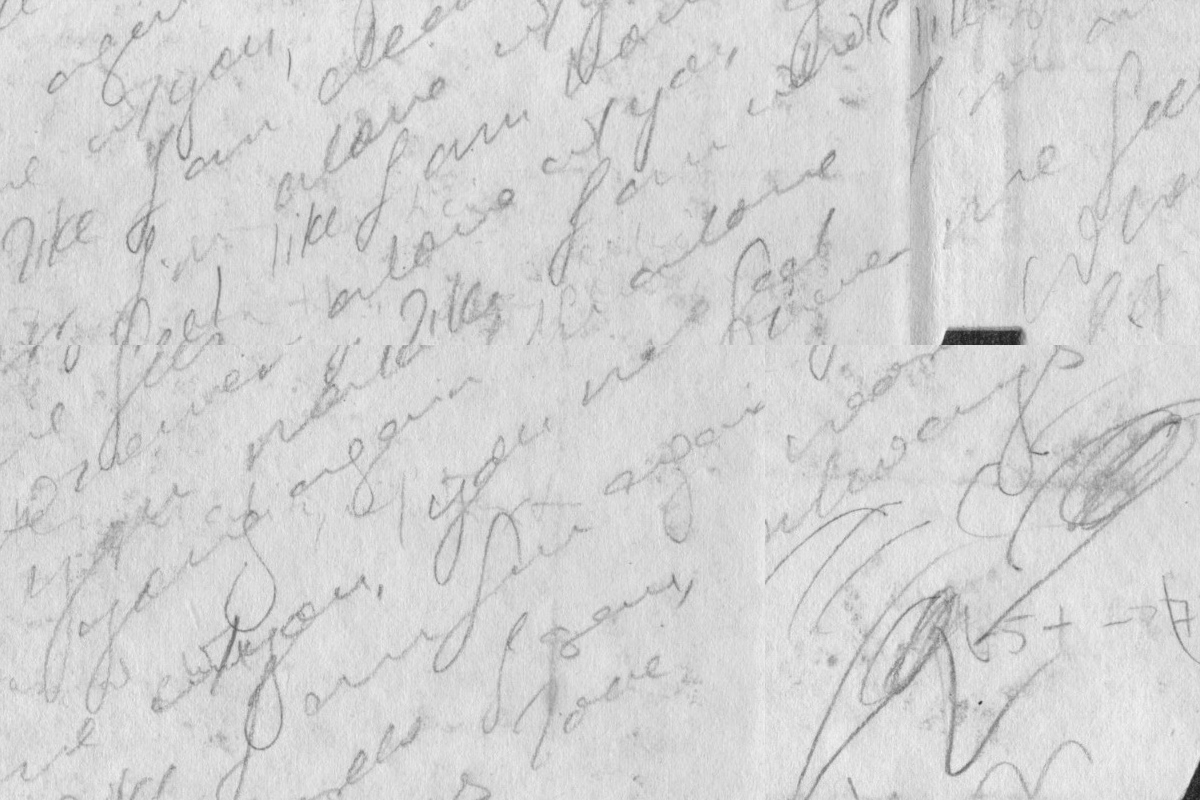

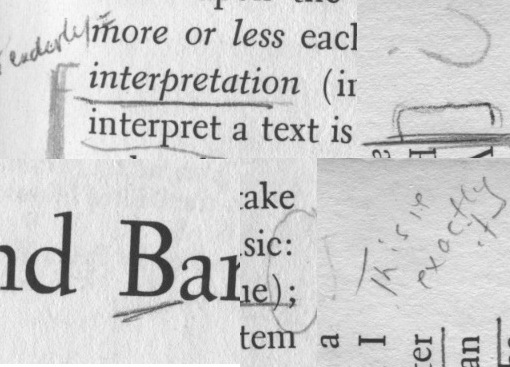

M ore

particularly, I am talking about the oil-stained thumbprints in a

library book, the dog-eared corners, the broken spines, the

squiggles, the abstract theorizations, the curses in the margin, the

highlighted phrases, the dirty limericks, and the underlined words. I

am thinking through such marks and marginalia as an uncanny sign of

life, a tenuously enduring presence of absent others, a sign of the

body in reading, and a certain reminder of the reader; not you or me,

the reader, but of other readers, assemblages and generations.

Looking at the margins of library books, we are faced with “the

space between the walls proper, the space of the joint”

(Bloomer, 1993, p. 167), and thus the space where things can be taken

productively and provocatively out of joint. Though the margins of a

book are often regarded as a field of overdetermined emptiness, they

are also breaches of form, and a place of potential fissure, on “the

verge … where something is about to happen” (Bloomer,

1993, p. 95).

ore

particularly, I am talking about the oil-stained thumbprints in a

library book, the dog-eared corners, the broken spines, the

squiggles, the abstract theorizations, the curses in the margin, the

highlighted phrases, the dirty limericks, and the underlined words. I

am thinking through such marks and marginalia as an uncanny sign of

life, a tenuously enduring presence of absent others, a sign of the

body in reading, and a certain reminder of the reader; not you or me,

the reader, but of other readers, assemblages and generations.

Looking at the margins of library books, we are faced with “the

space between the walls proper, the space of the joint”

(Bloomer, 1993, p. 167), and thus the space where things can be taken

productively and provocatively out of joint. Though the margins of a

book are often regarded as a field of overdetermined emptiness, they

are also breaches of form, and a place of potential fissure, on “the

verge … where something is about to happen” (Bloomer,

1993, p. 95).

However

smudged and unreadable, the extra-textual trace is always a burden, a reminder of the inescapable existence of

others, and of ourselves as an other. As space is taken up in the

margin—and as it signifies the fact that space is really never

blank at all, and that absolute absences, short of death, are

impossible—there is an inevitable loss (of innocence, of any

semblance of complete comprehension), though “it is often

loss,” as Ahmed (2006b) has written, “that generates a

new direction” (p. 19).

is always a burden, a reminder of the inescapable existence of

others, and of ourselves as an other. As space is taken up in the

margin—and as it signifies the fact that space is really never

blank at all, and that absolute absences, short of death, are

impossible—there is an inevitable loss (of innocence, of any

semblance of complete comprehension), though “it is often

loss,” as Ahmed (2006b) has written, “that generates a

new direction” (p. 19).

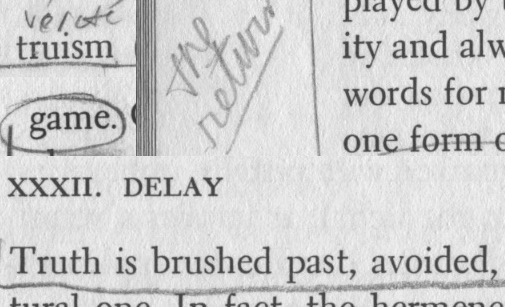

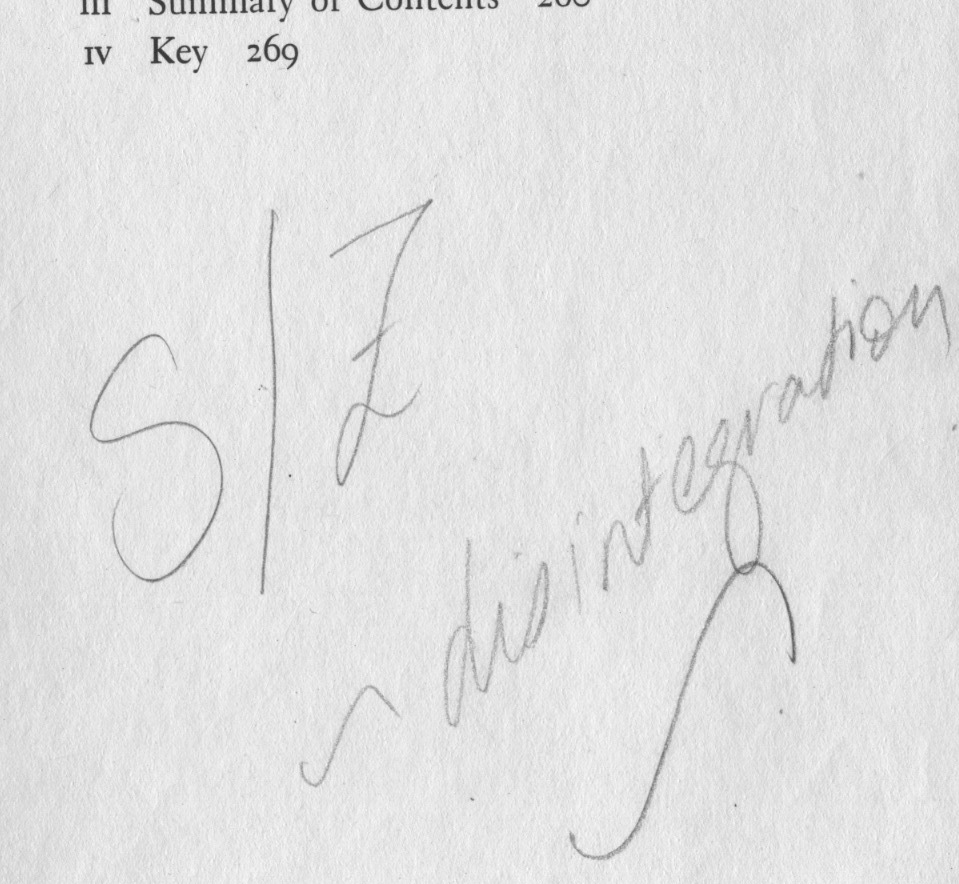

I  was

well into my Master’s degree at the University of Ottawa, when

I started running up against this thing called poststructuralist

theory, and it all seemed so new and foreign to me, but foreign like

a poem that you love despite an utter lack of understanding; the

words threw me for a loop. I tended to immerse myself, bathe myself,

humming the words, thinking such rapture would instill understanding.

I checked out Roland Barthes’ S/Z (1974) from the

library, and I fell deeply in love with this “series of

fragments” (Gallop, 2011, p. 33). There was a drive and a

thrall in these words that moved me well, and I was apparently not

the first to be so thrown. There was a unique type of “social

evidence” (Dohlstrom, 2011, p. 116) in this particular copy of

Barthes’ book, which was filled with all types of marginalia,

and which was just what I needed to experience at the time; a wordly

performance that put “the notion and the boundaries of text

to the test” (Dohlstrom, 2011, p. 124).

was

well into my Master’s degree at the University of Ottawa, when

I started running up against this thing called poststructuralist

theory, and it all seemed so new and foreign to me, but foreign like

a poem that you love despite an utter lack of understanding; the

words threw me for a loop. I tended to immerse myself, bathe myself,

humming the words, thinking such rapture would instill understanding.

I checked out Roland Barthes’ S/Z (1974) from the

library, and I fell deeply in love with this “series of

fragments” (Gallop, 2011, p. 33). There was a drive and a

thrall in these words that moved me well, and I was apparently not

the first to be so thrown. There was a unique type of “social

evidence” (Dohlstrom, 2011, p. 116) in this particular copy of

Barthes’ book, which was filled with all types of marginalia,

and which was just what I needed to experience at the time; a wordly

performance that put “the notion and the boundaries of text

to the test” (Dohlstrom, 2011, p. 124).

In  my

multiple encounters with this particular copy of Barthes’ work,

I could not help but read the author through these

polyphonically-sounded scrawlings, which at times put his voice

“literally in the background” (Dohlstrom, 2011, p. 126),

and which made me “attentive to the regularities, norms and

boundaries of our conceptions” (p. 128) of reading. Though I

had no idea of the context of these anonymous musings, these

scribbles of non-sense worked to unsettle my questions of sense and

of place. As the limit-case pushes us to the brink of the sense of

our readings, through which we can interrogate the status of, or the

privilege afforded to, the brink itself, I asked myself the question

of who was allowed to speak in the act of reading, whose voice was

the loudest, and how we could ever satisfactorily distinguish between

such an “ear-splitting … murmur of voices”

(Dohlstrom, 2011, p. 123).

my

multiple encounters with this particular copy of Barthes’ work,

I could not help but read the author through these

polyphonically-sounded scrawlings, which at times put his voice

“literally in the background” (Dohlstrom, 2011, p. 126),

and which made me “attentive to the regularities, norms and

boundaries of our conceptions” (p. 128) of reading. Though I

had no idea of the context of these anonymous musings, these

scribbles of non-sense worked to unsettle my questions of sense and

of place. As the limit-case pushes us to the brink of the sense of

our readings, through which we can interrogate the status of, or the

privilege afforded to, the brink itself, I asked myself the question

of who was allowed to speak in the act of reading, whose voice was

the loudest, and how we could ever satisfactorily distinguish between

such an “ear-splitting … murmur of voices”

(Dohlstrom, 2011, p. 123).

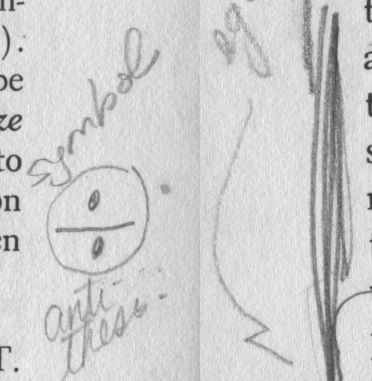

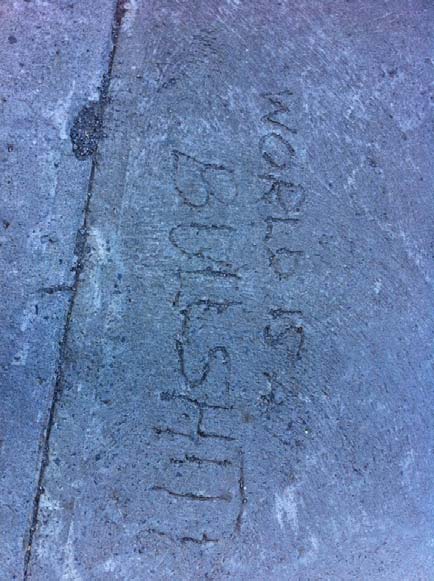

In her

writing on the cultural meanings of marginalia in Anglo-Canadian

cookbooks, which functioned in part as scrapbooks passed down through

families, friends, and generations, Golick (2004) has noted that “the

lowly cookbook without its marginalia is missing its soul” (p.

113), and it is interesting to note the use of the word “its,”

which here signals possession and ownership. The marginalia,

unidentified and spectral, is illegitimate, namelessly remaindered,

and owned by no one, and thus becomes owned by the book itself, an

ownership which transforms the book into something that is markedly

other than what it previously was: “a counterpart, an

antithesis, or an anti-edition” (Dohlstrom, 2011, p.

125). To think on this copy of Barthes’ text as a body of

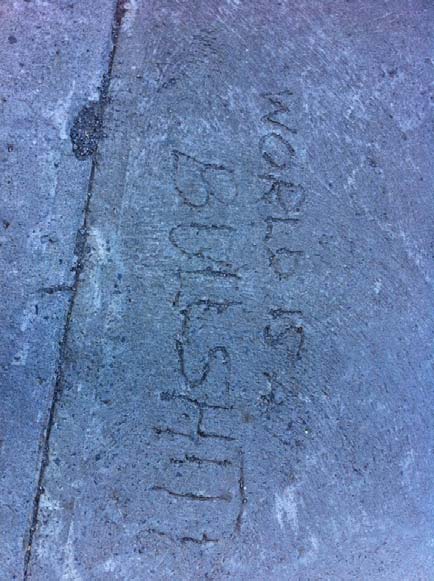

architecture, these graffitied scribblings also operate as such, but

as opposed to a body of structural and Cartesian logic that appears

ideologically immovable, this is a “minor architecture,”

which has been described by Bloomer (1993)—with reference to

Deleuze and Guattari—as “o perat[ing]

in the interstices of … architecture. Not opposed to, not

separated from, but upon/within/among: barnacles, bastard

constructions … An other writing upon the body” (p. 36).

This is a type of tattoo, and a form of sidewalk scrawling (see the

image to the left).

perat[ing]

in the interstices of … architecture. Not opposed to, not

separated from, but upon/within/among: barnacles, bastard

constructions … An other writing upon the body” (p. 36).

This is a type of tattoo, and a form of sidewalk scrawling (see the

image to the left).

Coming

back to this same text a few years after my initial encounter is a

disconcerting experience, and I have to admit I am surprised that it

is still in circulation. The spine is now broken, but the notes

persist. Have they been added to? Have certain ones been removed?

Which of them did I write myself? I am not sure, and it is this very

hesitancy that allows me to understand the ways in which rereading

can inform, and indeed, obscure, “what we are looking for now

and what we have sought in the past” (Spacks, 2011, p. 242). To

reread is to engage in the echoed life, and like the echo in a cave,

it returns necessarily transformed, yet recognizable still. Such

notions of repetition and displacement are at the heart of our

discussions surrounding the uncanny: the troubling question of

unintended repetition, the unknown extent of unavoidable

displacement, the knowledge that something always remains, the

uncontrollable mutability of memory, and the fact that we never read

alone. Reading in (and through) the margins, as Irwin and O’Donoghue

(2012) have described it, provokes in the reader an “openness,”

which leaves “traces of understanding rather than techniques,

skills, methods and lessons” (pp. 227-228). While such

“openness” may be uncertain and unreliable (a reader may

hate, love, or find themselves confused in the face of such

interventions), such is undeniably the case for all “realities

… for which there are no pre-existing models” (p. 227).

Part

9: The Enigma of Now

For

epistemologies of teaching and reading to adequately encounter what

de Lauretis (2008) has called “the enigma of now” (p. 4),

we must first recognize that for the now to be read, we can

only “sustain the impact of the real” (p. 9) in

reworkings of our earlier experiences; and through reference to a

type of double temporality that Freud has titled Nachträglichkeit,

commonly referred to in English as deferred action,

retroaction, or afterwardsness. In this formulation,

the traumatic meaning of a repressed memory may remain silent until

revived at a later date, and thus, as Freud (cited in de Lauretis,

2008) has written in Project for a Scientific Psychology, “a

memory [can arouse] an affect which it did not arouse as an

experience” (p. 7). For the purposes of this article, the

implication here is that the fields of teaching and reading are

forever populated by multiple species of memories, both meaning-full

and meaning-less, interpretative terms whose suffixes remain

threateningly ambivalent and disturbingly variable. Moreover, these

are memories that, as Salvio (2007) has described, may “appear

absent but take up an uncanny presence in our classrooms” (p.

19). If we think of our psyche as text, and thus as enmeshed in a

circuit of reading, the process of articulating our subjectivity may

be best understood as one of “self-translation, detranslation

and retranslation” (de Lauretis, 2008, p. 120). This is, as de

Lauretis (2008) has noted, “‘an activity of production’,

a kind of text we weave and unweave in retranslating ourselves; a

text ever in progress, with its plurality, its overdeterminations,

its ongoing confrontation with the other” (p. 120). Such a text

often does not make sense, and it is with an overarching knowledge of

this potential non-sense—as a zone where meanings refuse to

cohere—that I have shared these insignificant stories from my

own experiences of teaching and reading.

Notably,

when I write insignificant, I’m referring to the fact

that of the stories I have here retold, not one has anything to do

with the formal worlds of teaching: methods of evaluation,

formulations of cross-curricular competencies, disciplinary

strategies, lessons in essay writing, professional development, etc.

Yet, the very insignificance of these stories alerts us to what

Maxine Greene (2003) has called “the odd isolation of the

teaching role” (p. x); the alienation that accrues in teaching,

despite the fact that, as teachers, we are always surrounded by

bodies. The problem is, we often do not know how to read through the

text of passing experience as something meaningful, especially when a

particular experience is thought of as trivial, fleeting, and

ostensibly useless; and I am here thinking about the possibilities of

reading in its most productive and creative sense—as with Pitt

and Brushwood Rose (2007), this is “a problem of making

emotional significance” (p. 329), and of recognizing the ways

in which significance might be deferred. By focusing only on the

immediately “educational” and observable, we run the risk

of remaining emotionally and intersubjectively illiterate—our

surroundings remain as alien, unapproachable, or unreadable.

Along

with the obscure fact that those memories we forget are often of

greater consequence than those we remember, I am thus here arguing

towards a reassertion of the notion of insignificance in theories of

teaching, learning, and reading, and that only through exploring the

meaning of insignificant stories can we bear the terrible burden of

the uncanny well—turn it into a readable thing (which

again, does not imply surmountable). Though prison is certainly a

different environment from school, Bernard Stiegler (2009) drew on

his own experiences as a prisoner in describing the relation between

significance and insignificance: “In prison, that which, today,

is very prominent and consistent, laden with meaning and in that

sense, ‘significant,’ never fails to become, tomorrow,

indifferent, totally insignificant, and the very opposite of what it

was” (p. 27). This understanding—that significance is in

no way a permanent attribute—strips away from the object of

study, whether experience or a piece of literature, the capacity for

determining significance. Instead, this capacity rests squarely on

the position of the person experiencing, remembering, or reading.

In

further characterizing the insignificant, Stiegler (2009) proposed

that:

There

is nothing insignificant in itself, and that what can be

insignificant are not the things themselves, or in themselves, but

the relation I have or rather that I do not have with those things,

such as I articulate and arrange them. (p. 27)

Along

with Stiegler, then, I have considered in this article the importance

of voicing insignificant stories, and that rather than insinuating a

method that looks to the most memorable, the most notable of human

experiences, I propose a practice of looking to the trivial, and

arranging such experiences in a fashion that allows the reader to

find “significance in the insignificant” (p. 27).

When confronted with the uncanny, it is not, therefore, a matter of

accepting the strangeness implied, but of positioning ourselves newly

(and strangely) in relation to such strangeness, moving it in and

out of significance. It is about working creatively with the

uncanny, even as it does its work on us.

As the

beast of experience is bloodied, his entrails removed and dragging

behind, vomiting blood—as words—in a forward-like

fashion, the least we can do is read in his body, see where the cuts

and the blows have been placed, see what the form of his stumblings

now take (and possibly, stop up or cut deeper a wound or two). As

Kristeva (1991) has written, “A certain imbalance is necessary,

a swaying over some abyss, for a conflict to be heard” (p. 17).