Figure 1. Community Sampling Strategy.

The Community Strength Model: A Proposal to Invest in Existing Aboriginal Intellectual Capital

Michelle J. Eady

University of Wollongong

The Community Strength Model discussed in this paper evolved from my previous research (Eady, 2015) with the Point Pearce Indigenous community in South Australia. The research aimed to connect and complement longstanding sociological and cultural theories of learning with a relatively new model of e-learning that is influenced by Indigenous culture. That research refined 11 design-based principles to guide respectful implementation of technologically based learning into Australian Indigenous communities. The principles remain timely as Australia rolls out a National Broadband Network, which will bring high-speed internet into many Indigenous communities for the first time.

Funding and Support

The South Australian Department of Further Education, Employment, Science and Technology’s Digital Bridge Unit donated funds and support to the Point Pearce research project. The manager of the Digital Bridge Unit, a unit which promotes digital literacy, approached Indigenous communities to explain the project and gauge interest while the project was achieving University of Wollongong ethics approval.

Community Selection Process

Figure

1. Community Sampling Strategy.

Figure 1 shows the strategy used to select Point Pearce. Three communities expressed interest in participating. I visited each of them and discussed their needs, the depth of the research and the community commitment that participation would require. One community wanted to improve Indigenous people’s prospects of achieving employment at the local mine; however, interest seemed to be driven by a literacy practitioner who was not local. Another interested community was already committed to a range of training programs and international school trips, which caused concern about any additional time commitments. The community manager said the community was already doing well and the research might benefit another community more. Because of that suggestion, the communities’ specific interests, and verbal support for the research, I chose to work with the third community that had expressed interest: Point Pearce. Point Pearce is located 280 kilometres north west of Adelaide. It is home to the Narungga people. The community, of about 100 members, remains strong and committed to their land and language. Five community members including school staff and the council manager expressed support for the research.

Design-Based Research Approach

The Point Pearce qualitative study used a design-based research approach (van den Akker, Gravemeijer, McKenney, & Nieveen, 2006) to guide the investigation of synchronous technologies and how they could be used to build literacy in Indigenous communities. Design-based research offered the advantage of integrating practice and theory, while valuing interactive relationships between the researcher, the literature, literacy practitioners and community members. The approach also enabled data that was collected through interviews and focus groups to carry the authentic voice of Indigenous community members who contributed to research questions and draft guiding principles. The design-based research (Reeves, 2006) was undertaken in four phases, illustrated below.

Research Approach Phases

Figure

2. Design-based research approach phases (Reeves, 2006).

Phase 1: Analysis of practical problems by researchers and practitioners in collaboration. A literature review identified practical problems associated with synchronous technologies and literacy skill acquisition. These were analysed in collaboration with 11 practitioners who had worked with Indigenous communities, community members and/or with Indigenous literacy issues, in either a face-to-face or computer-based capacity. During this phase it became apparent that despite the value of information and communication technologies, a framework to guide the use of synchronous technologies for adult literacy learning in Indigenous communities did not exist.

Phase 2: Development of solutions informed by existing design principles and technological innovations. A collaborative community engagement project with the Point Pearce community was created, based on draft guiding principles drawn from the literature, and consultation with literacy practitioners and the community.

Phase 3: Iterative cycles of testing and refinement of solutions in practice. Point Pearce study participants took part in synchronous platform training sessions to prepare for the presentation of their work in the online environment. Three iterations of the presentation took place. Focus group members had the opportunity to discuss their thoughts and make changes to improve the next iteration of the project. In this way, Indigenous ways of knowing were consistently incorporated and the draft guiding principles were refined. This work can be viewed in its entirety (Eady, 2010), or in papers published from the work (Eady, 2015; Eady, Herrington, & Jones, 2010).

Phase 4: Reflection to produce “design principles” and enhance solution implementation. During this phase, 11 design-based principles emerged to guide future research in the areas of online learning and Indigenous adult literacy learners (Eady, 2015). This phase also revealed the Community Strength Model.

The Community Strength Model

The Community Strength Model has four components that can be specific to Indigenous communities. The Community Strength Model can be extrapolated and applied in various contexts, or used as an independent model. It is cyclical, as these components are unlikely to be fixed, and will need to be regularly reviewed and updated.

Components

Figure

3: Components of Community Strength Model.

Community strength. Strengths will be present in every Indigenous community. In the Narungga context, during the time of this study the community was preparing to celebrate its 140th anniversary and this was recognized as a community strength. A large celebration was being planned and the community was bursting with pride and buzzing with excitement. Another strength was the way community members came together and worked for a common cause: the community’s struggles in relation to their education system.

Shared learning experiences. The second component of the Community Strength Model is an environment for shared learning experiences to take place. At Point Pearce, when community members were given an opportunity to share their concerns in a non-threatening environment, they decided to incorporate into the project the traditional language, Indigenous knowledge, and the Elders’ wisdom. Shared learning experiences were meaningful tasks that were relevant to the cause and were supported by skillful teachers, administrators and mentors. The tasks resulted in further sharing of experiences, harnessing the value of oral tradition, which is common to Indigenous people throughout the world.

While Western education techniques focus on developing the mind, Indigenous societies have long valued the development of survival skills, such as observation and memory, to ensure continuation of culture, language, and citizenship (Des Jarlais, 2008). Friesen and Lyons Friesen (2002) describe the use of legends by Indigenous groups in Canada as “the intricately-devised [sic] deliberate process of verbally handing down stories, beliefs, and customs from one generation to the next” (p. 64). Hughes and More (1997), the Australian National Training Authority (2002), and Dyson (2002) include the following learning strategies and preferences for Indigenous adult learners:

learning through doing, rather than observing;

learning from real-life experiences;

a focus on skill acquisition for specific tasks;

careful observation before practising new skills;

trial and feedback approaches;

the interest of the group taking precedence over the individual;

a holistic approach of comprehending the entire concept before putting it into practice;

strong representation of visual-spatial skills;

deployment of imagery;

contextual learning as opposed to abstract concepts;

unprompted learning;

an aspect of personal, face-to-face instruction; and,

an emphasis on people and relationships.

Despite these commonalities, advocates of Indigenous learning caution against a one-size-fits-all approach. Instead, a more personalized approach is recommended, specifically designed to assess the learning style of each adult learner and prevent stereotyping (Australian Flexible Learning Framework, 2003; Eagles, Woodward, & Pope, 2005; Hughes & More, 1997). The same authors suggest that learning for Indigenous adults is best achieved through trial and error in real-life circumstances. In Yolngu society in Western Australia, for example, Indigenous knowledge is traditionally taught by Elders through imitation and observation, which is congruent with the societal value of maintaining traditional customs (Dasen, 2008; Verran & Christie, 2007).

Authentic community voice. Group members who had experienced the most Western education reflected on another data category, which the researcher termed authentic voice. Authentic community voice includes intergenerational sharing and passing down of culture and wisdom, as well as strong communication skills in traditional languages, people’s first language, and English. The five components contribute to authentic community voice follow.

Community concerns. When a safe environment enabled people to express themselves naturally and to be respected for what they had shared, this authentic community voice fostered confidence to raise concerns about community well-being in the Point Pearce focus group. Community focus group (CFG) members raised concern in general conversation, but also in relation to photographs they were sorting into categories for their e-learning project. Some of these discussions included concerns about employment issues, lack of literacy skills, and worry for the future of the children in the community. One saw literacy as a way of making people safer to express their concerns:

I used to think [literacy] was all about reading and writing. But I don’t know as I’ve gotten older I think it’s more important that we teach to be able to challenge and question and understand what’s being said to them and having the confidence to be able to do that. So literacy is having the ability to do public speaking, having the ability to be confident in challenging someone else. Or know that it’s okay to clarify any questions you know for your own understanding. So that’s what I think literacy is. (Ally, CFG, October 13, 2010 )

Power of position. Some Point Pearce participants were concerned with the lack of power of position that they had in the greater Westernized world. The members felt that they were getting further behind the way of the wider society especially in the area of computers and related technologies. The power of literacy and learning were seen as tools that would strengthen the voice of the community and that could be used to help the community to be confident and be heard as an important entity who had rights and needs as a viable Australian community. The issue of the unknown future of the local school brought forth the need to express these concerns and be heard in an equal and respectful way.

The group discussed how literacy can empower a person, and a community, to rise above an oppressed state and speak up for their rights. One participant explained:

Literacy to me means power because it’s a power of language that will get you wherever you want to go, so that’s what literacy means to me, it’s a power base and if you don’t have it you’ve sunk, you know, and I’ve actually seen people without literacy go into to Centrelink and fill in a form and they can’t do it, they can’t even write their own name. So it’s a shame job, it’s a shame thing, they feel very embarrassed and they’re told quite categorically that, you know, you’re an idiot because you can’t write and you can’t read and you can’t, you know, compute. So it’s a deep shame that people feel because they do not have the literacy and so literacy in my book is a power base. Aboriginal people come from another language base, and we have to learn the literacy and the language of a dominant group because we want to work in a world that’s not of our own making and to do that you have to have the literacy in the dominant group but I like to believe that it can be. (Ally, CFG, October 13, 2010)

Strength of Elders. The voice of Indigenous Elders is a particularly awe-inspiring gift. In the Point Pearce research project, three Elders participated in the collaborative community engagement project and contributed to the creation of the online synchronous presentation. These Elders provided facts about the project, stories that enhanced the journey and provided first-hand recollections of the early years of education in the community. Many of the focus group members heard stories and learned things that they had never been told before as a result of their participation in the collaborative community engagement project.

Traditional language. Another important aspect of authentic community voice was the use, preservation, and in some cases the revitalisation of traditional language. It was very important to the Point Pearce community that portions of their presentation were done in their traditional language. Audio files of the local children singing songs in their traditional language were also added to the presentation. In some cases, an interpreter may be required for a greater understanding of the content and expression of what is being discussed. One participant explained:

Literacy like to us is, is being literate in your own language. Because I think if you’re literate in your own language and you have a good understanding about the culture and the way [our] people do things, then I think you’re confident to be able to tackle anything. (Eden, CFG, October 13, 2010)

Battiste (2008) defines Indigenous knowledge as a multifaceted system of knowing which encompasses “the complex set of languages, teachings, and technologies developed and sustained by Indigenous civilizations” (p. 87). Within Indigenous communities there are often rules governing the passing of knowledge, specifically in relation to spoken and unspoken knowledge (Brady, 1997). Within the protocols of knowledge transfer is the importance of preserving the uniqueness of local knowledge, which will aid the preservation and social order of the culture and community (Brady, 1997; Des Jarlais, 2008; Kinuthia, 2007; Kinuthia & Nkonge, 2005).

Indigenous ways of knowing. Warner (2006), using the term “Native ways of knowing,” describes Indigenous knowledge as “acquired and represented through the context of place, revolving around the needs of a community and the best efforts to actualize a holistic understanding of the community’s environment” (p. 150). Expanding from the individual notion of Western thought and intellect, Indigenous knowledge challenges the individual to view relationships in the context of the community, natural environment and a global perspective (Cajete, 2000). Regarded as much more than an instrument implemented to fulfill one’s innate sense of curiosity, Indigenous knowledge bears a specific and significant role in Indigenous communities. Brady (1997) writes, “The desire to ‘know’ is not sufficient reason in Aboriginal societies for receiving knowledge” (p. 418).

Point Pearce participants believed that literacy and education needed to incorporate a strong Indigenous component, with one stating that education needs to be “immersed in culture.” The participant suggested literacy helps people position themselves to be heard, while also giving them a strong sense of who they are and their identity as an Indigenous person:

You know, like, I’ve always grown up with this belief that, you know, the Government make decisions, they make laws and it’s all about keeping people in their places. And, you know, I did say that education empowers Aboriginal people to then stand up…because we do need those freedom fighters to stand up and say, “Hey we won’t be putting up with this anymore.” And, you know, this is what needs to happen and, and you know and, I guess ninety-nine point nine percent of the time, um, it’s only a very few that stand up. …those people that do stand up and be counted are the ones that make a difference. And if an Aboriginal is strong in their identity they know where they come from…they know where they belong, they know who they are, then everything just falls into place. And, you know, it doesn’t matter what sort of background…how dysfunctional families are, um,…or how supportive families are, if they know who they are then they can achieve anything. And that’s why it’s really important that through education we teach about the culture and we teach about the language and we strengthen that and then we teach them the curriculum. And it does go hand in hand. Like I said the only way out of poverty and the only way to make changes is if we have that strong foundation of education [literacy] and culture. (Eden, CFG, October 13, 2010)

Goals, Directions, and Development. The final element of the cyclical Community Strength Model focuses on creating manageable, community-wide, relevant goals and directions that lead to further community development. Community strength can grow from learning experiences based on authentic voice and strong community attributes. This improves confidence, which can lead to the community’s directions and development being further identified and articulated. The Point Pearce community’s goal was to tell a wider audience about the importance of the local community school and its role in preserving culture and language.

Point Pearce residents had a deep concern for their children and the future generations of the community. The group hoped to see the school re-open for older children as well and identified this as a direction they would like to pursue. These goals and directions led to larger community development directives which required community strength, which comes from an authentic voice, which fosters learning experiences to move further forward with goals, direction and development. The circle continues as the community strengthens.

The Community Strength Model Relative to a Broader Theoretical Framework

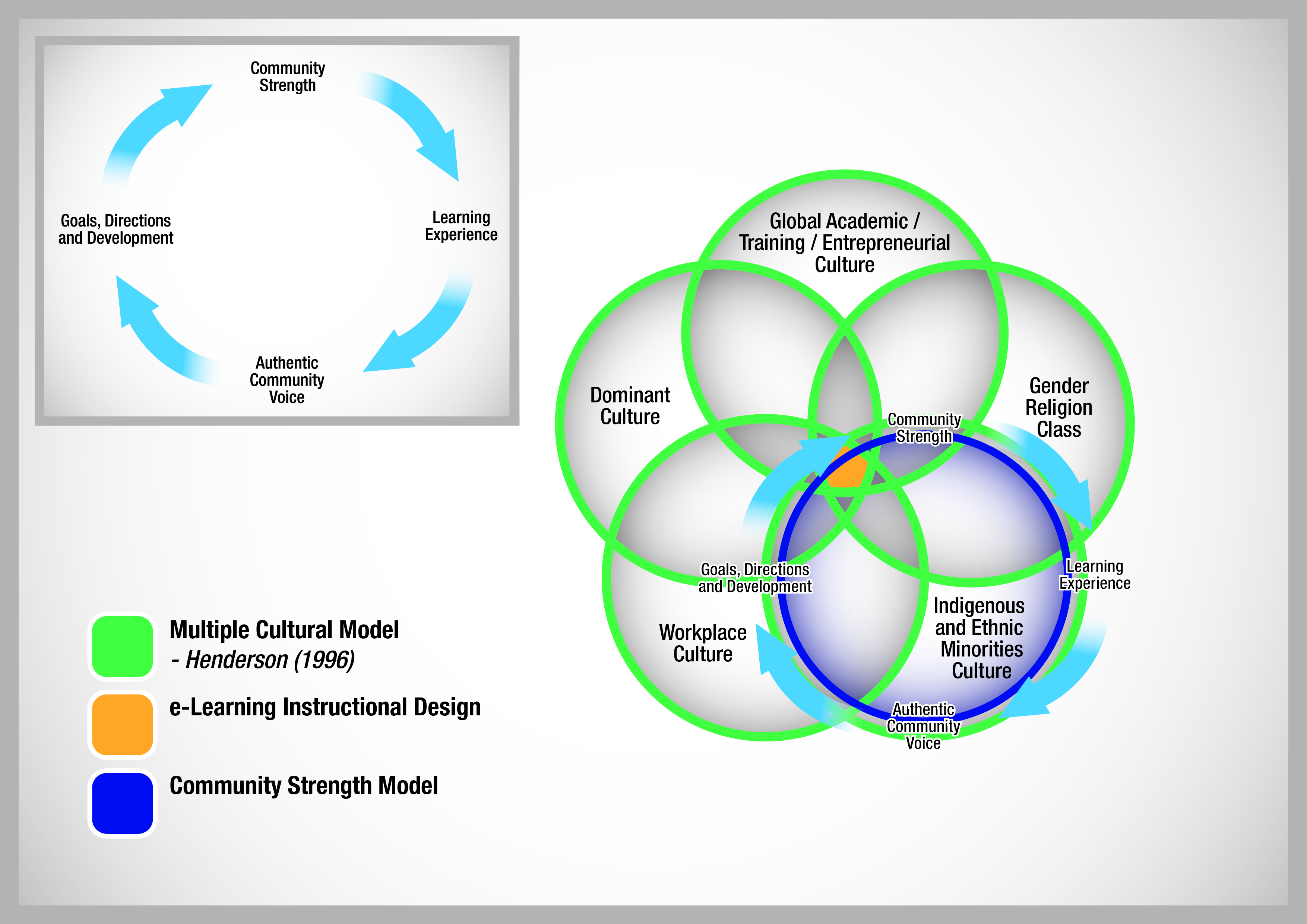

Multiple Cultural Model

The

Community Strength Model is presented next as an extension of the

Multiple Cultural Model (Henderson, 1996).

Figure 4: The Community Strength Model relative to the Multiple Cultural Model.

Henderson’s (1996) Multiple Cultural Model of e-Learning design for Indigenous communities features five interlocking circles that represent the detailed cultural considerations that are relevant to Indigenous communities. The Multiple Cultural Model provides a framework for designing an effective e-learning environment, which promotes equality for learners from minority groups. Henderson (1996) presented this model in the context of a tertiary education program that was delivered to Indigenous communities.

The Point Pearce study, however, applied Henderson’s (1996) concepts to an adult literacy-learning environment within an Indigenous community. The components of Henderson’s five circles were altered to reflect the specific context of the Narungga people and the model was used to facilitate collaboration and interconnectedness between the Narungga community’s five subcultures. These five subcultures, which are shared with other Indigenous communities on local, national, or global levels, have been identified in other research (Eady & Woodcock, 2010; El Sayed, Soar, & Wang, 2011; Henderson, 1996). They are as follows:

dominant culture,

workplace culture,

global academic training and entrepreneurial culture,

gender, religion and class, and

ethnic minority and Indigenous culture.

As seen in Figure 4, Henderson’s (1996, 2007) circles interlock to form an apex, which represents the most desirable scenario for e-learning to take place in an Indigenous community setting. The dominant culture in Henderson’s research was Westernized society, which influences the outcomes of e-learning and Indigenous communities’ involvement with e-learning experiences. Henderson (2007) expresses concern that e-learning applications and resources do not include relief from “the rich get richer and the poor get poorer” cultural paradigm of Westernized society, and that issues such as power, control and disadvantage are not readily addressed in the context of e-learning.

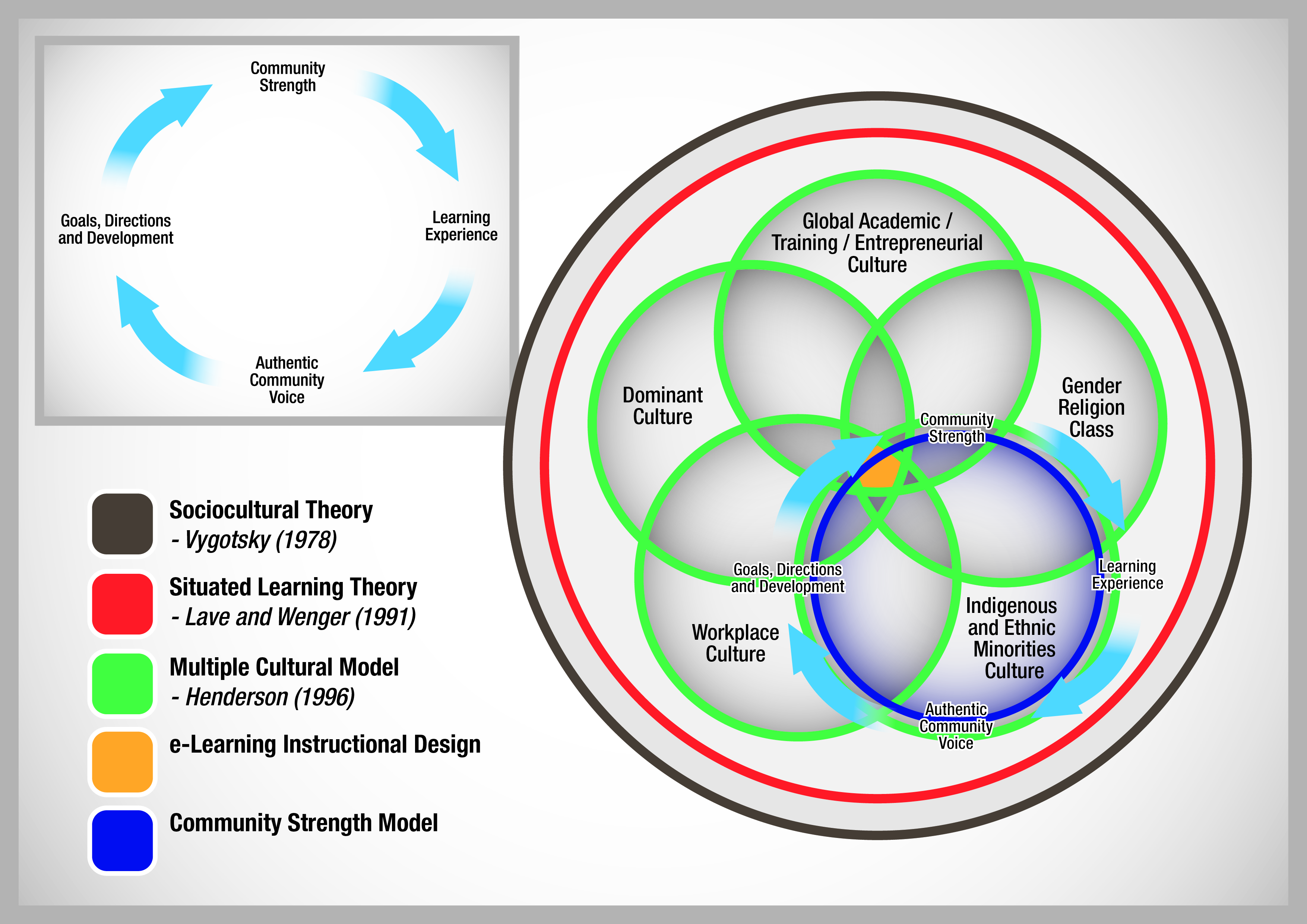

Situated Learning Theory

The next layer of the theoretical framework is Lave and Wenger’s (1991) Situated Learning Theory, as illustrated below.

Figure 5: The Community Strength Model relative to the Multiple Cultural Model and Situated Learning Theory.

This theory suggests that social interaction and collaboration result in common learning groups called “communities of practice” (Lave & Wenger, 1991). The theory also suggests that effective learning takes place within authentic contexts. Lave and Wenger’s (1991) interpretation of Vygotsky’s (1978) sociocultural theory suggests the context in which knowledge is obtained and applied in daily situations governs the cognitive retention of the information being taught (Bell, Maeng, & Binns, 2013; Chin & Williams, 2006; Stein, 1998). This presents learning as a sociocultural phenomenon, in which the learner acquires knowledge through actively participating in specifically influenced contexts, rather than being an action of the learner obtaining information from an academic body (Bell et al., 2013; Stein, 1998).

At each turn of the research the Point Pearce community focus group provided meaningful input to the process of learning new computer and literacy skills. When it was decided that the topic choice, direction, and creation of the presentation would be managed by the focus group, and the result would be something that the group created together, one group member said:

That would be good because it’s always been like that in the past, that we’ve always had to rely on these – no offence – but white fellas to come in and show us how to do them and then they’re still doing things for us, instead of us learning how to do it and then do it on our own. And I think that’s the skills we need to build on. (Julie, CFG, November 5, 2010).

Lave and Wenger (2003) have also developed a model of situated learning that is based on a process of engagement in a community of practice, where learners commune through mutual participation in activities related to their learning. Building relationships over time, participants in communities of practice continue to develop meaningful relationships and resources that contribute to both the group and the individual’s knowledge base (Bell et al., 2013; Lave & Wenger, 1991; Stein, 1998). Data presented in this research lend further support to Lave and Wenger’s perspectives within Indigenous contexts.

Research participants from the Point Pearce community came together as a community of practice around a common goal. They became passionate about the case that they were supporting and presenting. Throughout the project, focus group members were learning things about their culture and community from each other. In this way, the collection of learning and (re)membering, as discussed by Haig-Brown (2005), enabled everyone in the community, young and old, to come together to share their stories and their personal journeys. They pieced together the “fragments” (Haig-Brown, 2005, p. 90) of history and created a fuller, more meaningful story for everyone involved.

Focus-group members learned and retained this new information, which enabled them to convey it more meaningfully. They decided to create a presentation about the past and present value of education to the Narungga people of Point Pearce. Much like the students in the group described by Haig-Brown (2005), these community focus group members were “all people with a commitment to learning more, using the knowledge, and passing it on to others who have less experience with it than they do” (p. 96). The personal connection to the content and the desire to share their stories fostered a fruitful and vibrant community of practice and brought meaning and relevance to the literacy skills that were achieved as a result. These skills included practical applications such as sorting, categorizing, discussing, scanning, cropping, sequencing, creating scripts, public speaking, and facilitating an online classroom. Other literacy and life skills were also nurtured and valued, including commitment, dedication, patience, sharing, discussing, listening, interpersonal relations, teamwork, and taking pride.

In keeping with situated learning theory, this research demonstrated the value of a community of practice and learners having common interest in an Indigenous context. Lave and Wenger (2003) suggest that a community of practice’s context, beliefs, and values encourage and enable the acquisition of new skills; hence this theory being represented as the second circle in the theoretical framework underpinning this research.

Sociocultural Theory

The final layer in the theoretical framework is another equally important theory—the Sociocultural Theory (Vygotsky, 1978), which is illustrated below as the largest circle and overarching theme of the research.

Figure

6: The Community Strength Model relative to the Multiple Cultural

Model, Situated Learning Theory and Sociocultural Theory.

The premise of Sociocultural Theory is that quality social interactions can develop higher-order functions when they take place in cultural contexts (John-Steiner & Mahn, 1996; Meskill, 2013; Scherba de Valenzuela, 2002; van der Veer & Valsiner, 1991). Based on this philosophy, adults will learn more effectively when they socialize with other learners in a positive environment and instruction is deemed more effective when it is connected to cultural learning that is relevant to the learner (Meskill, 2013; Scherba de Valenzuela, 2002). This would suggest that learners function best in social settings, working together with others, collaborating and communicating in collective ways.

The study with the Point Pearce community demonstrated the importance of Indigenous adults being comfortable in their community environment. Focus-group members grew up knowing one another and had been through life’s challenges and successes together. They shared an understanding of where the Narungga people originated and their history, the realities of today’s community, and the hopes for the future. There was potential for Narungga culture to be negatively impacted should the community lose its school, and this was of grave concern to the community and its members.

The community had a sense of ownership over the research project and a commitment to work together to complete it. The council was preparing to celebrate the community’s 140th anniversary. The focus group discussed creating a presentation to celebrate the anniversary, which placed an emphasis on the school, how it came to be and how it had changed over the years. One focus group member reminded the rest of the group:

Can I just say too that with the issues that we’re facing around the school at the moment, about kids and their attendance and the possibility that the school might close…we don’t have that many kids, that if something’s done around the school that we can then also online present to the Education Department about the importance of the school, that might help with keeping the school here. (Kammie, CFG, November 5, 2010)

We were just talking about it the other day and something that is really important to our community is this school. There are not many kids that go here and it is always being said that they [the school board] might close it down. We thought maybe we could do a presentation for the school board or something and we could learn some skills on the computer to do that. (Julie, CFG, November 5, 2010)

With this understanding, the focus group members’ voluntary participation and commitment of time could be positioned in a broader socio-cultural context.

Vygotsky’s (1978) theory suggests that guided social interactions serve a cognitive function that occurs in the zone of proximal development: the difference between what a learner can do independently and what can be accomplished cognitively with guided support from more knowledgeable others (Karlström & Lundin, 2013; van der Veer & Valsiner, 1991). This scaffolding was evident throughout the research, during training in how to use the synchronous platform, and as people undertook isolated tasks such as scanning, creating a presentation, and editing audio files. Throughout the study, the researcher observed the process of moving the learner from assisted performance to greater self-assisted and self-regulatory competence (Henderson & Putt, 1999; Karlström & Lundin, 2013; van der Veer & Valsiner, 1991). A more knowledgeable peer assisted the less knowledgeable learners, so they were then able to help others. The project showed how effective learning was achieved when Indigenous learners felt comfortable in their learning environment and when new tasks were relevant and culturally appropriate. This further supports Vygotsky’s (1978) socio-cultural theory’s significance in adult literacy learning settings in Indigenous communities.

Relationship to Community-Based Participatory Research

The Community Strength Model has many similarities to the recently emerging community- based participatory research method, as both focus on developing and implementing bi- culturally inclusive research practices (Broad, Boyer, & Chataway, 2006; Broad & Reyes, 2008; Sadler et al., 2012). Each model prioritizes the importance of using decolonization practices that respect all involved parties and utilize the strengths of the Indigenous community (Broad & Reyes, 2008; Simmonds & Christopher, 2013). In this way, both the Community Strength Model and the community-based participatory research method seek to give a voice to the marginalized and place the Indigenous participants at the centre of the research (Broad & Reyes, 2008; Simmonds & Christopher, 2013).

Simmonds and Christopher (2013) recognize that community-based participatory research is “less a method than an orientation to research” (p. 2186). Within this paradigm, researchers serve the community by creating knowledge that is relevant to it (Broad et al., 2006; Simmonds & Christopher, 2013). This requires ongoing and open communication between the researchers and the community, allowing the community members to shape and design the research and allowing the researchers to hear about the needs of the community and the issues that require attention (Sadler et al., 2012). Each of these elements of the community-based participatory research method is also found in the Community Strength Model, where a cyclical process provides the structure for facilitating respectful research within Indigenous communities. The Community Strength Model suggests that not just research, but all learning experiences can be built on desires and strengths within a community and that these strengths then shape the future direction of learning and growth for communities.

Conclusion

The concept of a Community Strength Model emerged from this research. The model may present itself in a variety of different ways in different communities. However, in the context of the Narungga people of Point Pearce, it enhanced understanding of the value of harnessing Indigenous cultural logic in online learning and teaching environments. The Community Strength Model is built on the premise of Henderson’s Multiple Cultural Model (Henderson, 2007), which incorporates ethnic minority and Indigenous culture as a cultural logic to be taken into consideration in the development of e-learning activities in Indigenous communities. The model also assumes that members of Westernized cultural logic understand how to view Indigenous cultural logic in the context of e-learning environments. In a closer examination of Henderson’s Indigenous subcultures in relation to this research, the process of this project helped to clarify the meaning of Indigenous cultural approaches to learning and successful bi-culturally inclusive practices.

Many Indigenous communities have embraced and utilized synchronous technologies for literacy enhancement, the sharing of knowledge and cultural traditions, and the acquisition of vocational skills. However, this is not always a simple undertaking, as there are factors to consider when attempting to balance different knowledge systems, both Westernized education and Indigenous ways of knowing.

Although the literature indicates that synchronous learning technologies have the ability to contribute significantly to Indigenous communities, there also lingers within the communities, the reminder of the turbulent history of formal education, which inflicted, on a global level, “damaging practices of indoctrination, assimilation and colonization” (White-Kaulaity, 2007, p. 561). Systems of formal education and attempts at assimilation to Western values have historically denied Indigenous people access to ways of learning that reflect their unique ways of living, traditions, and knowledge (Battiste, 2008; Des Jarlais, 2008; Friesen & Lyons Friesen, 2002; United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2006). In its attempts to assimilate Indigenous people to European culture and social systems, the European model of education resulted in “great linguistic losses worldwide” (Battiste, 2008, p. 86).

Synchronous learning technologies proposed by non-Indigenous sources are often viewed suspiciously by local leadership. Often equated to dominant educational practices associated with past colonisation/assimilation systems, these scholastic measures are likely viewed as potential threats of a mass invasion of mainstream education practices and materials contrary to local values, traditions, and customs (Facey, 2001; Hodson, 2004; Hunt, 2001). Similarly, current models of distance education being implemented for Indigenous learners are largely representative of the technology, heritage, and scholastic traditions of the developed Western nations, and lack culturally appropriate learning components that have been proven a factor to the success of adult learning (Australian Institute for Social Research, 2006; Ramanujam, 2002; Sawyer, 2004; Young, Robertson, Sawyer, & Guenther, 2005).

To address this challenge, Ramanujam (2002) cautions against blindly copying Western models of distance education and instead recreating Indigenous models, which, “will have greater relevance and strength than the copied or adopted models” (p. 37). Such models will likely gain the acceptance of the introduction of blending Western technology and Indigenous learning styles since prototypes with curriculum and learning objectives based on Western perspectives are often rejected in Indigenous communities (Taylor, 1997).

The Community Strength Model and design-based principles played a significant role in addressing these complex factors, paving the way for the Point Pearce community’s multiple successes. The Point Pearce project resulted in the Narungga community focus group members gaining the skills to use the synchronous platform, not only as participants but also as facilitators and teachers.

As researcher, I first gained permission and built relationships with community members, who in turn welcomed the project to take place. After building acquaintances over time, I invited community members to attend a focus group discussion. During this discussion, in a safe, known environment for the group, the community members were able to express their concerns and identify needs in the community. These needs and concerns were strengthened by the need for power of position within the greater community, by Elders’ wisdom, by traditional language, and by Indigenous knowledge, all of which led to a desire to learn meaningful and relevant literacy and computer skills. Considerate scaffolding from me, as researcher, was essential to support the motivation and the agency of the community members in their journey of learning the new skills.

With the acquired skills the community members were able to share their story with others and take pride in their accomplishments. This environment fostered further discussions about other ways that they could share strengths and concerns for their community. These learning experiences fostered further discussions about continued directions of the local school and developments that could be supported using the synchronous platform. The learning experiences that took place during this research were successful, in part, due to the relevant content for the learners, combined with the strengths and the components of those strengths in the Indigenous community.

Experience working with the Point Pearce community supports the value in paying close attention to the Community Strengths Model when collaborating with Indigenous communities in the implementation of new technologies. The model’s inherent respect for the cultural needs and traditions of Indigenous community members reflects that every Indigenous person has a voice and every Indigenous community has strengths and wisdom beyond Westernized culture’s recognition and understanding.

It is time for Eurocentric educational approaches to take a backseat to Indigenous knowledge and ways of knowing and let the culture, language, and wisdom of these amazingly talented, big-hearted, kind, and welcoming people lead the ways in which they wish to approach learning. A top-down approach often results in limited success. Strength lies in diversity and differences; policy makers and curriculum developers at every level must learn to use their power to embrace these strengths in order to make the difference that is needed for Indigenous learners and communities everywhere.1

References

Absolon, K., & Willett, C. (2005). Putting ourselves forward: Location in Aboriginal research. In L. Brown & S. Strega (Eds.), Research as resistance: Critical, indigenous, and anti-oppressive approaches ( pp. 97-126).Toronto, ON: Canadian Scholars’ Press/Women’s Press.

Australian Flexible Learning Framework. (2003). Cross-cultural issues in content development and teaching online. Quick guides series-Australian Flexible Learning Framework, 9, 2004.

Australian Institute for Social Research. (2006). The digital divide: Barriers to e-learning - Final report. Retrieved from http://www.ala.asn.au/

Australian National Training Authority. (2002). Adapting online resources for Indigenous learners. http://toolboxes.flexiblelearning.net.au/documents/docs/indighortreport.doc

Baskin, C. (2005). Storytelling circles: Reflection of aboriginal protocols in research. Canadian Social Work Review, 22(2), 171-187.

Battiste, M. (2008). The struggle and renaissance of indigenous knowledge in Eurocentric education.In M. Villegas, S. Neugebauer, & K. Venegas. (Eds.), Indigenous knowledge and education: Sites of struggle, strength, and survivance. (pp. 85 - 91). Cambridge, MA: Harvard Educational Review.

Bell, R. L., Maeng, J. L., & Binns, I. C. (2013). Learning in context: Technology integration in a teacher preparation program informed by situated learning theory. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 50(3), 348-379.

Brady, W. (1997). Indigenous Australian education and globalisation. International Review of Education, 43, 5-6.

Broad, G., Boyer, S., & Chataway, C. (2006). We are still the Aniishnaabe Nation: Embracing culture and identity in Batchewana First Nation. Canadian Journal of Communication, 31(1), 35-58.

Broad, G., & Reyes, J. A. (2008). Speaking for ourselves: A Colombia—Canada research collaboration. Action Research, 6(2), 129-147. doi:10.1177/1476750307087049

Cajete, G. (2000). Indigenous knowledge: The Pueblo metaphor of indigenous education. In M. Battiste (Ed.), Reclaiming Indigenous voice and vision. Vancouver,BC: UBC Press.

Chin, S., & Williams, B. (2006). A theoretical framework for effective course design. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 2(1), 12-21. Retrieved from http://jolt.merlot.org/

Dasen, P. R. (2008). Informal education and learning processes. In P.R. Dasen & A. Akkari (Eds.), Educational theories and practices from the majority world (pp. 25-48). New Delhi, IN: Sage.

Des Jarlais, C W. (2008). Western structures meet Native structures: The interfaces of educational cultures. Charlotte, NC: Information Age.

Dyson, L. (2002). Design for a culturally affirming Indigenous computer literacy course. Paper presented at the 19th Annual Conference of the Australasian Society for Computers in Learning in Tertiary Education (ASCILITE), Auckland, NZ.

Eady, M. (2010). Creating optimal literacy learning environments using synchronous technologies to support Aboriginal adult learners effectively: A Narungga perspective. (Doctoral dissertation, University of Wollongong).

Eady, M. (2015). Eleven design-based principles to facilitate the adoption of internet technologies in Indigenous communities. International Journal of Social Media and Interactive Learning Environments, 3(4), 267.

Eady, M., Herrington, A., & Jones, C. (2010). Literacy practitioners' perspectives on adult learning needs and technology approaches in Indigenous communities. Australian Journal of Adult Learning, 50(2), 260-286.

Eady, M., & Woodcock, S. (2010). Understanding the need: Using collaboratively created draft guiding principles to direct online synchronous learning in Indigenous communities. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 6(2), 24-40.

Eagles, D., Woodward, P., & Pope, M. (2005). Indigenous learners in the digital age: Recognising skills and knowledge. Paper presented at the Australian Vocational Education and Training Research Association, Brisbane, AU. Retrieve from https://avetra.org.au/documents/PA045Eagles.pdf

El Sayed, F., Soar, J., & Wang, Z. (2011). Development of a culturally appropriate interactive multimedia self-paced educational health program for Aboriginal health workers. Paper presented at the Enhancing Healthcare Education, Research and Practice Symposium, Hong Kong.

Facey, E. (2001). First Nations education by internet: The path forward, or back? Journal of Distance Education, 16(1). Retrieved from http://cade.athabascau.ca/

Friesen, J., & Lyons Friesen, V. (2002). Aboriginal education in Canada: A plea for integration. Calgary, AB: Detselig.

Haig-Brown, C. (2005). Toward a pedagogy of the land: The indigenous knowledge instructor program. In L. Pease-Alvarez & S. R. Schecter (Eds.), Learning, teaching, and community: Contributions of situated and participatory approaches to educational innovation. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Henderson, L. (1996). Instructional design of interactive multimedia: A cultural critique. ETR&D, 44(4), 85-104.

Henderson, L. (2007). Theorizing a multiple cultures instructional design model for e-learning and e-teaching. In A. Edmundson (Ed.), Globalized e-learning cultural challenges (pp. 130-153). Hershey, PA: Information Science.

Henderson, L., & Putt, I. (1999). Theorizing audio conferencing: An eclectic paradigm. Canadian Journal of Educational Communication, 27(1), 21-37.

Hodson, J. (2004). Aboriginal learning and healing in a virtual world. Canadian Journal of Native Education, 28(1/2), 111-122.

Hughes, P., & More, A. (1997). Aboriginal s ways of learning and learning styles. Paper presented at the Annual Conference for the Australian Association for Research in Education, Brisbane, AU.

Hunt, P. (2001). True stories: Telecentres in Latin America and the Caribbean. The Electronic Journal on Information Systems in Developing Countries, 4(5), 1-17. Retrieved from http://www.ejisdc.org/ojs2/index.php/ejisdc/article/view/25/25 /

John-Steiner, V., & Mahn, H. (1996). Sociocultural approaches to learning and development: A Vygotskian framework. Education Psychologist, 31(3/4), 191-206.

Karlström, P., & Lundin, E. (2013). CALL in the zone of proximal development: Novelty effects and teacher guidance. Computer Assisted Language Learning: An International Journal, 26(5), 412-429.

Kinuthia, W. (2007). Instructional design and technology implications for Indigenous knowledge: Africa’s introspective. In L. E. Dyson, M. Hendriks, & S. Grant (Eds.), Information technology and Indigenous people (pp. 105-116). Hershey, PA: Information Science.

Kinuthia, W., & Nkonge, B. (2005). Perspectives on culture and e-learning convergence. In G. Richards (Ed.), Proceedings of E-Learn: World Conference on E-Learning in Corporate, Government, Healthcare, and Higher Education 2005 (pp. 2613-2618). Chesapeake, VA: AACE.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Melbourne, AU: Cambridge University Press.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (2003). Legitimate peripheral participation in communities of practice. In R. Harrison & F. Reeve (Eds.), Supporting lifelong learning: Perspectives on learning (pp. 111-126). London, UK: Taylor & Francis.

Meskill, C. (Ed.), (2013). Online teaching and learning: Sociocultural perspectives. Advances in digital language learning and teaching. New York, NY: Bloomsbury.

Ramanujam, P. (2002). Distance open learning—Challenges to developing countries. Delhi, IN: Shipra.

Reeves, T. C. (2006). Design research from a technology perspective. In J. Akker, K. Gravemeijer, S. McKenny, & N. Nieveen (Eds.), Educational design research (pp. 52-66). London, UK: Routledge.

Sadler, L. S., Larson, J., Bouregy, S., LaPaglia, D., Bridger, L., McCaslin, C., & Rockwell, S. (2012). Community-university partnerships in community- based research. Progress in Community Health Partnerships, 6(4), 463-469. doi:10.1353/cpr.2012.0053

Sawyer, G. (2004). Closing the digital divide: Increasing education and training opportunities for Indigenous students in remote areas. In New practices in flexible learning. Australian flexible learning framework. Brisbane, AU:ANTA. Retrieve from http://www.voced.edu.au/content/ngv%3A36187

Scherba de Valenzuela, J. (2002). Sociocultural theory. Retrieved from https://www.unm.edu/~devalenz/handouts/sociocult.html

Simonds, V. W., & Christopher, S. (2013). Adapting Western research methods to indigenous ways of knowing. American Journal of Public Health, 103(12), 2185-2192.

Stein, D. (1998). Situated learning in adult education. ERIC Digest, 195, 1-7. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED418250.pdf

Taylor, A. (1997). Literacy and the new workplace: The fit between employment-oriented literacy and Aboriginal language-use. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 18(1), 63-80.

United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2006). Education for all. Literacy for life. EFA global monitoring report. Retrieved from http://www.uis.unesco.org/Library/Documents/gmr06-en.pdf

van den Akker, J., Gravemeijer, K., McKenney, S., & Nieveen, N. (Eds.). (2006). Educational design research. Oxon, UK: Routledge.

van der Veer, R., & Valsiner, J. (1991). Understanding Vygotsky. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Verran, H., & Christie, M. (2007). Using/designing digital technologies of representation in Aboriginal Australian knowledge practices. Human Technology, 3(2), 214-227.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Warner, S. (2006). Native ways of knowing: Let me count the ways. Canadian Journal of Native Education, 29(2), 149-164.

White-Kaulaity, M. (2007). Reflections on Native American reading: A seed, a tool and a weapon. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, 50(7), 560-569.

Young, M., Robertson, P., Sawyer, G., & Guenther, J. (2005). Desert disconnections: E-learning and remote Indigenous peoples. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/

_____________

Endnote

1Social Location of Author: It is important for researchers to identify themselves within the context of their projects, especially in research conducted alongside Indigenous partners (Absolon & Willett, 2005; Baskin, 2005). I have always had a great respect for, and kinship with, Indigenous people and their culture. My career as an educator has taken me to the far north of Canada where I taught primary school and lived for more than a decade. My passion and desire to work with Indigenous people and to help others see the strengths in their communities comes from experiencing the social norms and expectations of these communities first hand. My work has also included a collaborative initiative called Good Learning Anywhere, a project using synchronous technologies to help Indigenous adults in Ontario Canada reach their literacy goals. This project went on to become a province-wide initiative and has won many awards including the Council of the Federation Literacy Award in 2007.

In 2008, I was offered an international scholarship from the University of Wollongong, Australia to commence a PhD, which looked at implementing a similar program for Indigenous learners in Australia. This time, however, it was important that I did not decide for others what they needed to learn. Instead, my focus was building on existing strengths and extending learning opportunities from them. I worked with Aunty Barbara Nicholson; an Indigenous representative on the university ethics committee and respected community Elder, to ensure that the study followed ethical guidelines for Indigenous peoples.

I take great care in all areas of ethical research. My work always leads me to learn side-by-side with Indigenous people and not do research on Indigenous people. Such was Indigenous people’s active participation in one of my projects that all participants wanted to be identified and share ownership. At the end of the project, we held a special graduation ceremony for everyone who participated. The Elder who took part in the project, Aunty Alice Rigney, read and approved of each page of the work and was also invited to be the guest speaker at the graduation ceremony. She said,

There are many ways of learning and this process is another futuristic method of getting people to gain knowledge. It seems that we go from what was in the past to what is possible in the future. However, we must retain those valued cultural aspects of our lives which strengthen us like our family, culture, language and identity. Like everything, when we unite, there are those things that are outstanding and those that we need to build on because sometimes we come at the subject from different eyes and that’s okay too because overall we want to make educational outcomes the best that we can make it for the most disadvantaged people on the planet in all countries everywhere. Those who have been dispossessed, deprived, disempowered but have survived. We have to make it right and sometimes using modern technology of the future is another method of this empowerment. This project helped us to see this and go in that direction” (Eady, 2010, p. viii).

Late 2015, it was confirmed that my great grandmother was a member of the Mi'kmaq Nation of Atlantic Canada. I have been, and will always be, an ally for Indigenous people, and an advocate for Indigenous rights and treating Indigenous people with respect. I believe it is my responsibility, as an academic, and a person, to uphold and demonstrate these values.