Using Art-Based Ways of Knowing to Explore Leadership and Identity With Native American Deaf Women

Damara Goff Paris

Emporia State University

One of the least represented Indigenous voices in scholarly research is that of Native Americans who are Deaf, particularly women. To date, literature about Native American Deaf women have been short biographies or generalized dissertations. (Baker, 1996; National Multicultural Interpreter Project, 2000; Paris & Drolsbaugh, 1999; Paris & Wood, 2002)

Part of the difficulty in finding study participants from this small population has to do with the paucity of data regarding Native Americans who are Deaf. Demographic data on Native Americans who are Deaf has been largely overlooked, and is usually generalized to people with all ranges of hearing loss, rather than focusing exclusively on Deaf Native Americans who are primarily American Sign Language (ASL) users and consider themselves part of the Deaf community (Gallaudet Regional Institute, 2011; Miller, 2004; Pleis & Lethbridge-Cejku, 2007).

As a Deaf woman of Native American descent, and as a researcher who works with under-represented Deaf individuals who are Indigenous, I have long been concerned about the lack of literature that includes the perspective of this population. It is important to consider the inclusion of Deaf and Indigenous “voices” in research, particularly those who identify with two distinct cultural and linguistic diverse (CLD) populations. Without their perspectives, their issues continue to be largely ignored or overlooked, rendering them nearly invisible to the rest of the world.

This paper extrapolates upon visual arts products correlating to a larger phenomenological-narrative study of factors that influenced leadership identity development among American Indian Deaf women. The overarching research question that guided this portion of the study was “what does leadership mean to you as someone who is Deaf, Native American, and female?”

It is important to review relevant literature that is pertinent to leadership and Deaf Native American women and how several factors impact their worldview. An analysis of Native American women and leadership is provided as well as a discussion of how Deaf individuals view their identity as a cultural entity, rather than a pathological perspective of deafness as disability. In addition, historical parallels were drawn between the educational and societal oppressions that Deaf Community members and Native Americans experiences, with both communities being forced to relinquish their cultural identities and languages. A distinct commonality exists in visual-gestural languages that are used by both communities, demonstrating how Native Americans and Deaf individuals have bonded and mutually influenced their usage of signed languages. Finally, I discuss the importance of art making as an important means of expressing cultural knowledge for Indigenous and Deaf populations.

Literature Review: Native American Women and Leadership

A growing body of literature addresses the perspectives of Native American women who are in leadership positions (Barkdull, 2009; Chin, Lott, Rice, & Sanchez-Hucles, 2007: Fitzgerald, 2010; Lajimodiere, 2011; McLeod, 2002; Muller, 1998; Napier, 1995; Portman & Garret, 2005; Prindeville, 2000, 2004). There are no known studies on the leadership experiences of Deaf Native American men or women.

Much of the existing literature addresses the impact of Colonial America on the perceptions of Native American women and their loss of political power. Though it is acknowledged that each tribe is distinct, historically, women have led spiritual, political, educational, and economical decision-making in many tribes (Lajimodiere, 2011; Mihesuah, 2003). Clan mothers chose tribal leaders; preserved culture, language, and history; and oversaw education and social needs of the community. In some tribes, they even served as warriors, fighting alongside their male family members (Lajimodiere, 2011; Mihesuah, 2003; Perdue, 1998).

Native American men and women had distinctly separate, but powerfully equivalent, roles in overseeing the well-being of their people (Muller, 1998; Portman & Garret, 2005; Prindeville, 2000, 2004). When Eurocentric settler’s worldviews began to have tribal influence, particularly with government-required elected tribal councils and land allocations given to Native American men, women lost a considerable amount of influence within their own governments (Barkdull, 2009; Lajimodiere, 2011; Mihesuah, 2003; Napier, 1995; Portman & Garret, 2005; Prindeville, 2000, 2004). Today, however, an increasing number of tribal leaders are women, and they continue to focus on the preservation of history, allocation of economic resources, and the educational and social needs of the children.

Deaf as Cultural Identity

Deaf culture encompasses its own richly documented history, language, and heritage (Gannon 1989; Holcomb, 2012; Moore & Levitan, 2003; Nomeland & Nomeland, 2011; Padden & Humphries, 1988). This viewpoint differs from traditional scholarly or academic definitions of culture, which tend to refer to primarily to ethnicity. To be identified as a culturally Deaf person, a variety of factors are considered, including family background of deafness and inherited deafness, familial adoption of ASL as their primary language, or whether the person attended schools for the Deaf, and/or Gallaudet University. This differs from the pathological or medical viewpoint, which focuses on the physical state of being deaf.

“Deafhood” is an empowering concept in the Deaf community (Nomeland & Nomeland, 2011). The term has been offered as representative of a “process—the struggle by each Deaf child, Deaf family and Deaf adult to explain to themselves and each other their own existence in the world” (Ladd, 2003, p.3). Eschewing the pathological term of deafness, which often perceives that the deaf person needs to be medically cured, the exploration of Deaf as a cultural identity is encouraged by members of the Deaf community (Ladd, 2003 Nomeland & Nomeland, 2011). Because Deaf people view themselves as a cultural entity rather than disabled, research and literature often capitalizes the term “Deaf” to indicate cultural membership, while the lowercase “deaf” is ascribed to the physical trait of being deaf, to people who do not incorporate the usage of ASL, or otherwise do not consider themselves as culturally Deaf (Ladd, 2003; Moore & Levitan, 2003; Parasnis, 1998).

Effects of Educational and Language Oppression on Identity Formation

The blend of cultural influences are also important to consider for Native American Deaf individuals because they represent an intersection of two distinct cultures that have experienced parallel historical atrocities directed at their communities. Native Americans (and many Indigenous communities) have experienced cultural genocide by dominant, colonialist societies through education, particularly during the “boarding school era” between the 1880s and 1970s (Child, 1998; Evans-Campbell, Walters, Pearson, & Campbell, 2012; Fey & McNickle, 1959). In accordance with a philosophy of “‘killing’ the Indian to save the ‘man’” (Smoak, 2006, p. 304), Native American children were removed from their tribes and sent to boarding schools far from their homes. The intent was to eradicate their language, customs, clothing, and way of life. Native American children at boarding schools were ridiculed, beaten or starved, and forced into indentured servitude (Child, 1998).

Deaf individuals have also experienced oppression within educational institutions. Residential schools for Deaf children were established in the 1700s as placements for Deaf children to support learning and communication via sign language (Gannon, 1981; Nomeland & Nomeland, 2011). During the late 1800s, a debate surrounding the use of sign language in K-12 classrooms grew in America and internationally. Proponents of ASL maintained that Deaf children should be taught using a naturally occurring, visual- gestural language—ASL—while opponents advocated for the exclusive use of spoken language, which came to be known as Oralism (Winefield, 1987). During the 1880 International Conference of Instructors for the Deaf in Milan, Italy, a majority of international hearing educators in Deaf Education voted to endorse Oralism as the sole communication method for classroom instruction (Baynton, Gannon, & Bergey 2007; Winefield, 1987). For almost 100 years, ASL was suppressed in American classrooms. Horror stories of Deaf children being punished for signing became common, and Deaf people hid usage of ASL out of shame and fear (Nomeland & Nomeland, 2011).

Intersection of Visual-Gestural Languages

A commonality between the Deaf and Native American communities is their use of visual-gestural language (Davis, 2011; Davis & McKay-Cody, 2010; Paris & Wood, 2002). For centuries, Native Americans used a visual-gestural, or sign language, commonly referred to as Indian Sign Language (ISL), American Indian Sign Language (AISL), Native American Sign Language (NASL), or Plains Indian Sign Language (PISL) (Alford, 2002; Davis & McKay-Cody, 2010; Farnell, 1995). In the Native American community, visual-gestural language was used primarily to ensure that Deaf and hard of hearing members of their tribes had communication, and secondarily to communicate with other tribes that did not share a common language (Alford, 2002).

Sign language use in America has been documented among White inhabitants of Martha’s Vineyard in Massachusetts as early as 1600 (Van Cleve & Crouch, 1989). Approximately one-fourth of the islanders on Martha’s Vineyard were hereditarily Deaf or hard of hearing, with much intermarriage between Deaf and hearing families (Baynton et al., 2007). Laurent Clerc, a Deaf French man, came to America at the beginning of the 19th century to establish and teach at the first American school for the Deaf, adding elements of French Sign Language to what has since become modern American Sign Language (ASL) (Baynton et al., 2007; Nomeland & Nomeland, 2011; Van Cleve, 1999).

While Native American Signed Languages have waned in usage within tribes as English evolved as the dominant spoken language, many Native American Deaf individuals use a blend of ASL and American Indian Sign Language (AISL), which is typically derived from PISL. Recently, studies have been conducted regarding the potential contribution of PISL to earlier forms of ASL (Davis, 2011).

Art as Method of Inquiry

Art may serve as a non-verbal form of communication that provides an avenue for “hard-to-put-into words aspects of knowledge that might otherwise remain hidden or ignored” (Weber, 2008, p. 44). Art making is an important outlet for groups with a history of oppression by the dominant culture. Both Native Americans and Deaf Community members create art to preserve history and tradition, share their experiences, or make political statements intended to lead to social change (Durr, 2006).

Artmaking by Deaf Persons

Renowned Deaf artist Betty G. Miller (1989) wrote that visual art “is a way of life among Deaf people,” comparing the visual arts to the way hearing people enjoy and relate emotionally to music (p. 770). Sonnenstrahl (2002) concluded that despite the paternalism and oppression Deaf artists have faced for centuries, they still strive to aesthetically record their perspectives. Through the use of visual and tactile modalities, art is a safe means for Deaf people to communicate. Creation of art conveys “unexpressed thoughts or feelings” when words or signs seem inadequate (Horovitz, 2007, p. 20).

Artmaking by Indigenous Peoples

For Indigenous people, art is a way of sharing traditional crafts, dance, and storytelling (Neuman, 2006). Beyond the visual arts, from an Indigenous perspective, literature encompasses the oral tradition of storytelling, singing, dancing, symbols, handcrafted artwork and ceremonies (Snively & Williams, 2008). Storytelling has been long perceived as an embodiment of Indigenous knowledge (Bird, Wiles, Okalik, Kilabuk, & Egleand, 2009), re-establishing traditions and providing safer avenues for resistance to oppression and assimilation by the dominant culture (Sium & Ritskes 2013, p. III). The artistic expressions of Indigenous women are particularly relevant. Author Cynthia Chavez Lamar facilitated an art project with six Native women. Through this process, participants shared stories about earlier Native women artists whose creations were rejected by other artists and even members of their tribes (Lamar,2010).

Art-Based Ways of Knowing

Art-based inquiry empowers research participants in a way that emphasizes “locally meaningful inquiry” (Finley, 2005, p. 682). Visual arts-based participatory methods “involve research participants creating art that ultimately serves both as data, and may also represent data” (Leavy, 2009, p. 227). Finley (2005) cautions that investigators incorporating arts-based research with Indigenous populations must take care to include “antipaternalistic and anticolonist principles that forbid the researcher from speaking for people” who are capable of expressing their political and social perspectives (p. 76).

The use of visual arts as inquiry with Native Americans allows participants to select and create imagery expressive of Indigenous epistemologies. As a researcher, I am concerned with ensuring that I have incorporated methodology that places Indigenous participants (particularly for individuals who experience the intersection of racism, genderism, and disablism) firmly at the helm of the inquiry. The objective of this study is to provide a venue for Deaf, Native Americans who are women, to provide their perspective on what leadership means to them, using art-based ways of knowing.

Methodology

This paper extrapolates upon visual arts products correlating to a larger phenomenological-narrative study of factors that influenced leadership identity development among American Indian Deaf women. While other techniques were used to collect data on the phenomenon of leadership development for the overall study, the purpose for this portion of the study was to provide an opportunity for these women to share their ways of knowing through non-verbal images representing their lived experiences and perspectives.

I posed only one question: What does leadership mean to you as a Native American Deaf woman? I did not expound on the question, or define what leadership meant, allowing opportunity for individual interpretations. I provided art materials upon request, or reimbursed the cost of selected materials, and did not directly participate in the development of the visual imagery. I was available for consultation, as requested, while each woman processed her visualization of leadership.

Participants

The five participants selected for this study came from diverse backgrounds and leadership experiences. Each woman was affiliated with a different tribe. It is important to note that all of the women are American Indians. No Alaska Natives participated, thus the experiences of these distinct tribal communities are not represented. Because the Native American Deaf community is small, the identities of participants were held confidential, with tribal affiliations removed. The participants created their own pseudonyms.

Selection of the participants was based on recommendations from the Native American Deaf community. I contacted thirty-five men and women from this community through e-mails, videophone and in person to ask for names of Native American Deaf women whom they felt were leaders. I did not provide a definition of what leadership meant, leaving it to the community to determine what they considered women in leadership roles. While explanations for the recommendations were not solicited, many of the contacts commented on why they felt the women were leaders. Such comments included “She holds both Deaf and Native American traditions, providing guidance and wisdom”; “She is someone I admire, look up to, and want my children to emulate”; and “I trust her wisdom and dedication to our people.” Seven women were named, with some of the individuals receiving multiple recommendations.

As a Deaf woman of Native American descent, I had interacted with many of the individuals that were recommended throughout my experiences as a biographer collecting stories on Native American Deaf experiences for two books that were subsequently published (Paris & Droslbaugh, 1999; Paris & Wood, 2002). I also served in a leadership capacity national organizations of Native American Deaf individuals. As a result of my active membership in the community, there was rapport and trust, which expedited my relationships with the women recommended by the community, who I also knew on personal and professional levels.

Participant 1: Beulah

Beulah* was appointed as an Elder in a national Native American Deaf organization, and in this role provided support, wisdom and encouragement to Deaf individuals seeking cultural information about their Indigenous heritage. A member of an East Coast tribe, Beulah is in her late 70s. She became deaf at 18 months because of spinal meningitis. Her parents placed her in a residential school for the deaf several hours away from the reservation; she went home only during holidays and for the summer.

Beulah’s leadership and identity development. While Beulah grew up with ASL as her primary language, she felt disconnected from her Deaf peers. Her understanding of her identity as a Native American came through the lens of her Deaf peers. The negative stereotypes of Native Americans in the media, and the fact that there were few resources available at school to educate Beulah and her classmates regarding Native Americans, resulted in painful, discriminatory remarks from her Deaf peers. Beulah accepted these perceptions as facts, not understanding until later that they were stereotypes. “Oh, they really poked fun at me…telling me that Indians were mean and killed White people. I believed them” (Beulah, personal communication, April 9, 2012).

Beulah did not embrace her identity as a Native American woman until she was in her mid-50s. While she visited her family briefly over the years, communication was sporadic since no one in the family was fluent in ASL. It was not until she read a book about her deceased father, who had been a renowned civil rights activist for his tribe, did she discover the extent of her ties to her tribal community.

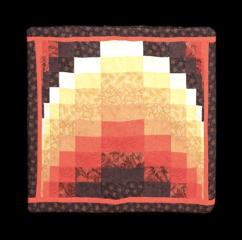

Despite the lack of communication, Beulah observed the traditional arts of community members during her visits. As she grew older and was drawn to her tribal roots, she sought out knowledge from women in the tribe and learned the quilting process, particularly star quilting. Today, Beulah creates quilts for community auctions, selling them to fund college tuition for tribal members. The walls at her home are lined with ribbons she has won at state fairs for her craftsmanship.

Figure 1. Beulah’s quilt

Beulah’s arts-based leadership concept. Beulah expressed her perspectives on leadership with a quilt project (Figure 1). She shared that the artistic process of making and selling quilts is important to her for many reasons. As a young woman, she desired a college education, but could not afford to attend, nor could her tribe assist her financially. As her artistic talents became known, she began auctioning off her quilts at annual tribal gatherings in order to raise money for young adults to attend college. Beulah began to influence other quilt makers and artists in her tribe to donate each year, therefore growing the funds to share with college students. By engaging in tribal art making, she felt that she was able to support youth in her community with opportunities to obtain higher education.

Beulah described how the vision of her leadership quilt came to her when she thought how many tribes in mountain regions go to pray during sunrise, beginning their days by asking for strength to nurture their communities. Her tribe believes in giving thanks to the Creator at the dawn of each new day. While Beulah recognized that not all tribal traditions incorporate sunrise prayers and not all tribal regions include mountains, she felt that the symbolism was universal, particularly for leaders, and that it was important to renew and strengthen oneself each morning in order to serve others.

Beulah identified quilt making as a way for her to understand her Native heritage. Through her fellowship with other women in her tribe, she was able to learn more about her tribal values, passing this heritage on to her child, grandchild, and members of the Native American Deaf community. Without this interaction, she felt that she would not have been able to develop her own identity within her tribal community.

Though she has fully embraced her Native American identity, Beulah remains active in the Deaf community through social events. “I am a Native American Deaf woman,” Beulah said. “I belong to both communities” (Beulah, personal communication, April 9, 2012).

Participant 2: Julie

Born Deaf and a member of an East Coast tribe straddling the United States and Canada, Julie* assumes a number of roles in the Native American Deaf, Deaf, and Native American communities. She serves as president of a non-profit organization for the Deaf and a council member of a national, non-profit organization for Native American Deaf individuals. In her tribe, she consults with parents whose children are Deaf, teaching sign language courses and providing support and wisdom on educational options for tribal Deaf children.

Though born on a reservation, Julie spent most of her childhood and adolescence in the dorms of a residential school for the Deaf. Upon high school graduation, she chose to go back to her home and marry a hearing tribal member who is now deceased. Currently in her 50s, she remains on the reservation surrounded by her children, grandchildren, and extended family members.

Julie’s leadership and identity development. Julie did not fully understand her role in the tribal community until she was in her late 30s. One reason that she was unfamiliar with tribal traditions was because her grandmother was also Deaf, and did not receive full access to cultural information to pass on to her children. The lack of signed communication between Julie and her parents further constricted the flow of information. It was not until she participated in Native American Deaf Spiritual Gatherings that she learned in-depth information about her own clan (Bear Clan). Today, she is an advocate for tribal Deaf children, ensuring an avenue for passing on information about tribal traditions.

Julie feels connected to the tribal tradition of fashioning tribal regalia and clothing to be worn at powwows. She learned to sew in elementary school, a skill that was introduced to her by her Deaf grandmother. Through participating in this creative endeavor, she was exposed to visual representations of tribal beliefs. Julie learned to make traditional costumes by observing, and through written communication with tribal women. However, she did not always understand what the regalia represented until she began teaching sign language within her community. As she advanced in her skill as a seamstress, she gained prominence on the reservation for crafting regalia used for dancing during tribal events.

Figure 2. Julie’s dreamcatcher

Julie’s arts-based leadership concept. Julie chose to express her concept of leadership through a dream catcher (Figure 2). Julie cut strips of dyed rawhide, and wove colored twine around a small metal hoop to form a small “spider’s web” design. She added beads and feathers around the hoop and picked small silver feathers and a bear charm to interweave into the web. Julie explained that dream catchers filter out good and bad dreams in different ways. Good dreams go through the web and down to the feathers, where they are retained so the dreamer can continue to experience them again. Bad dreams struggle through the web, get caught, and then released through the center of the web into the dawn, where they fade away in the sunlight. This imagery represented what Julie felt leaders needed—to filter the negative and focus on the positive traits of giving to their community.

Julie explained that the most significant piece of the dream catcher, for her, was the image of the bear. “This represents my clan and it is my heritage, which is my strength” (Julie, personal communication, April 10, 2012). Proud of her dual citizenship in Canada and the United States, Julie states both the Native American and Deaf communities contribute to holistic balance in her sense of identity. Julie commented: “I prefer socialization with the Deaf community the most because I am not left out of communication…I feel that I become involved in Indian spirituality and the Creator and learned to pray the Indian way” (Julie, personal communication, April 10, 2012).

Julie expressed concern that there are limited opportunities for Native Americans who are Deaf within the tribe. While she has occasionally experienced employment discrimination, Julie has been able to move beyond poverty due to the support of her children and the tribe. She hopes to serve as a role model for young adults in her tribe who are not gainfully employed, a support that she did not have during her formative years.

Participant 3: Zabrina

Born Deaf to a mother whose tribe comes from the Western and Midwestern regions, and a father of Canadian French descent, Zabrina* was not born on a reservation, nor has she experienced reservation life. Her father was in the military and she grew up moving to a variety of places across America, as well as the Pacific Islands. In her 50s, Zabrina is the executive director of a national organization for Native Americans who are Deaf.

Zabrina’s leadership and identity development. Zabrina did not have the opportunity to participate in the Deaf community as a young person. She grew up attending public schools and relying on speech reading to communicate. Feeling isolated from hearing and Deaf people and not understanding how she fit in with the Deaf and Native American communities, Zabrina recalls feeling anger and mistrust. It was not until early adulthood that she interacted with both communities. A spiritual leader took her under his wing and taught her many of the traditions of her tribe. Zabrina also took ASL classes and began to participate in Deaf Community events, finding comfort in the visual-gestural communication of other Deaf people.

Zabrina expresses her traditions, especially spirituality, through artwork. She sews, does beadwork, and paints. As Zabrina explored the issue of leadership in her art project, she expressed discomfort at being called a leader. She shared her perspective about why she found the label of leadership uncomfortable:

I guess I don’t really label myself as a leader. I just do for my people…I see the pros and cons of this label and recognize that what I do fits into that definition…It feels like bragging and I am not comfortable with that...Indians don’t tend to say “I” or “me”, we tend to say “we” or “us” or “our people” because we are a group, a family. (Zabrina, personal communication, June 3, 2012)

Figure 3. Zabrina’s medicine bag

Zabrina’s arts-based leadership concept. Zabrina created a medicine bag as her visual representation of leadership (Figure 3). She explained that what one puts inside of the bag (herbs, stones or a small gift given by others), becomes sacred. “You honor it,” said Zabrina, “and hold it close to you as part of your healing as your walk on your path on Mother Earth….to overcome something, reach a goal or achieve healing” (Zabrina, personal communication, June 3, 2012). This healing is for four major areas—mental, emotional, physical and spiritual. When one is healed, one returns the items inside the bag to Mother Earth.

Zabrina explained that the design on the outside of the bag symbolizes the path of leadership for Native American Deaf women. The circle represents the medicine wheel, as well as Mother Earth, also referred to as a turtle. Citing the Seven Cardinal Directions, she stated they were representative of the Creator, Mother Earth, the Four Directions, and the soul. The four directions represented her tribal colors. Zabrina attributed much symbolism to the number four (the four elements, the four directions, the four seasons, and the four cycles of life.).

As one traverses these four-part cycles, individual challenges are faced to encourage personal growth. Each cycle needs to be worked through until the healing is completed. Zabrina felt the symbolism of the four directions was particularly important for her. East signifies clarity, while South reminds her to demonstrate love and empathy when listening to others. West is representative of strength and courage, while North encourages prayer and connection to the Creator. Zabrina described the beading on the upper right side, which represents stars or nations. She pointed to the single bead on the other side of the bag, which represented her spirit and was placed as a reminder to attend to her soul.

The fringe at the bottom of the bag appeared to be backwards, with the suede side in contrast to the leather of the bag. “I did this on purpose. It is a reminder that life on this earth is not perfect. It is okay to make mistakes” (Zabrina, personal communication, June 3, 2012). Zabrina stressed that people who are in leadership roles must honestly portray the imperfection of life, which will assist one in personal growth.

Participant 4: Winona

Winona,* whose heritage includes Midwestern and Plains tribes, is a Deaf American Indian female in her late 30s. She affiliates mostly with her mother’s Midwestern tribe. A self-described “Urban Indian,” she did not grow up on a reservation. Her family maintained cultural ties, so she attended powwows at least four times a year. Winona is the director of a business that has clientele nationwide.

Winona’s family members were very active in her tribal community. She grew up with strong and independent female family members who were involved in tribal community events, including tribal councils and powwows.

Winona’s leadership and identity development. Winona’s hearing loss was discovered while she was attending preschool. After briefly attending a day school for Deaf children, she was placed in public school. This was difficult for her because she did not have an interpreter. Later, she had access to sign language services and her school experience improved.

As the only American Indian Deaf student in her school, she noticed immediately that she was “different,” particularly since other students did not attend powwows. Despite this difference, she felt more comfortable with her Indigenous roots than with being a Deaf person. “I think that it was easier for me to identify and be an Indian in that environment than Deaf. I always seemed to manage to pass myself off as a hearing person,” she said (Winona, personal communication, March 21, 2012).

During her college years, Winona met a number of other Deaf students and was able to fully integrate into the community. As a result, she began taking on leadership roles within the Deaf community, including the presidency of a non-profit organization for Deaf individuals. Today, Winona feels fully acculturated into both communities, although she has a special affinity with her Native American roots.

Figure 4. Winona’s female hoop dancer

Winona’s arts-based concept of leadership. Winona chose to draw a female hoop dancer as her visual concept (Figure 4). Since childhood, Winona has been a gifted hoop dancer. She has found this was a way to learn and emulate her tribal traditions, and has passed on these values to her four children, who are also hoop dancers. Her family has traveled extensively to perform at powwows and for international arts communities. Her home serves as a display of hoop dancing regalia, with her first hoop dance outfit on display as well as some of her children’s regalia.

Using her son’s crayons, she drew a Native American woman in dance regalia, holding out three hoops on each hand. On the right side of the page, she drew a Medicine Wheel, colored in the quadrants, and wrote out the different concepts that the four directions represented. She explained that hoop dancing is representative of the Circle of Life dancing in an out of a hoop demonstrates the struggles of life. Upon completion of the dance, she overcomes her challenges. “I drew the woman in hoop dance regalia because it represents me. I know I have freedom when I show my culture and my dances” (Winona, personal communication, March 21, 2012).

The circle, Winona said, represents the four directions and seasons—spring, summer, fall, and winter. She listed objects in her community that had circles—the bottom of a teepee, the drum, and powwows, which are always circular in movement. The circle represents an important leadership aspect to her, in that Native Americans often think in a continuous circle, “which also represents equality and harmony interconnecting with people. No one person is better than the other and that is one reason why the circle is sacred to us” (Winona, personal communication, March 21, 2012).

The six hoops and the circular shape of her beaded necklace represented the seven traditional values: respect, honesty, harmony, humility, courage, wisdom, and generosity. Winona emphasized that humility was important, despite the oppression her communities (Deaf and Native American) have experienced, while courage was necessary to ensure that they are able to protect themselves when needed. Winona also felt generosity in her community was abundant—that giving was part of her culture, particularly when celebrating life events.

Participant 5: Cortelia

Cortelia,* who became Deaf from a fever at two years of age, is in her early 60s and is enrolled in a Southern tribe. Her family has been with the tribe for several hundred years. Cortelia directs outreach services for educational institutions that serve Deaf and hard of hearing children.

Cortelia’s leadership and identity development. Cortelia was the only deaf child attending a tribal school and the majority of the teachers were not aware of resources to support language development during her formative years. “They did not know how to help me, so they just had me do artwork while other students were learning to read and write” (Cortelia, personal communication, April 21, 2012). As a result, she was illiterate until she transferred to a school for the Deaf when she was eleven. She vividly recalls visiting the school, stating:

It was a weird experience at that time. When I first arrived, all of the girls were White! I looked at my mother and looked at the girls and I said, “It’s the first time I met all White girls. And they talk with their hands.” (Cortelia, personal communication, April 21, 2012)

It took only two years for Cortelia to catch up with her classmates. Despite experiencing oppression in the school, often by White instructors (there was only one Native American Deaf male instructor at the school), she was determined to obtain higher education. She eventually completed her Master’s degree and counts among her job experiences directorship of a non-profit organization and administrator in a higher education program.

Figure 5. Charcoal drawing of a woman superimposed in trees

Cortelia’s arts-based leadership concept. Cortelia’s visual representation of leadership (Figure 5) focused on a woman superimposed into a background of swamp trees, which reminded her of her family’s backyard on the reservation. She rendered her artwork in charcoal. She was visibly moved by what she produced, remarking that it had been the first time in many years that she had sat down to sketch a drawing. Cortelia explained that the trees in her drawing were representative of her Native American Deaf people and the ages and sizes represented “Young to old, big to small” (Cortelia, personal communication, April 21, 2012). The water symbolized nourishment for the community. The woman in the background was drawn in the image of her daughter. “She represents all of us as she watches, encourages, and supports the growth of the trees. To me, that is what leadership means—support and growth of the people” (Cortelia, personal communication, April 21, 2012).

Cortelia credited both the Native American and Deaf communities with providing an influence on her leadership development. “The Indian community instilled strength, value, and a cultural belief system. But the Deaf community made it easier for me to go up and beyond in my career” (Cortelia, personal communication, April 21, 2012).

Successfully blending both worlds into one holistic identity, Cortelia believes balanced growth is critical to achieving leadership success through nurturing their communities. She felt that she had equal footing into both communities. She explained: “I feel that I incorporated both cultures into one. I am Native Deaf. It’s hard to separate the two” (Cortelia, Personal communication, April 21, 2012).

Discussion

While these visual representations of Native American Deaf Women’s leadership are diverse, three important themes relative to cultural and disability identities emerge from these five women: identification with Indigenous art forms, strength in spirituality, and evolution of cultural identities.

Identification With Indigenous Art Forms

The process of creating visual art provided a catalyst for discussing the ways in which traditional arts and values influenced the leadership perspectives of the participants. Winona centered her artistic piece on her hoop dance experiences. Ward (2014 described the hoop dance as a ritual among many tribes that merges the endless cycle between creatures and natural elements.

Beulah produced another traditional art form—quilting—to demonstrate elements of leadership characteristics. Her piece included the vivid use of earth tones to represent mountains and a rising sun. Though Europeans are credited with introducing quilt making to American Indians, early patchwork quilts were made by Chippewas by tying rabbit skins together prior to the use of cloth (Weagal, 2007). Native American women have since introduced their own tribal symbols and colors into the quilting process.

Zabrina chose to use another Native American craft (the medicine bag) to demonstrate tribal symbolism of leadership as a balance of mental, physical, spiritual, and emotional strength, with imperfections. The creation of a dreamcatcher by Julie represents a craft most often used by Plains tribes (Shore, Orton, & Manson, 2009). By releasing negative influences that leaders experience, Julie feels that positivity will assist Native American Deaf women leaders in tending to their communities.

Strength in Spirituality

Deeply rooted spiritual themes arose in the art renderings from each participant. Beulah offered prayer within the backdrop of a natural environment as an important source of strength for leadership. Cortelia focused on the natural elements for strengthening leadership, choosing the nurturing aspect of a Native American Deaf woman overseeing the symbolic growth of her people.

Both Winona and Zabrina included the medicine wheel, the four directions, and the symbolism of circular representation. These traditions are prevalent in many Indigenous populations and are used in research and therapeutic practices, which focus on healing and understanding the balance of life (Dapice, 2006; Gone, 2011; Lavallée, 2009; McCabe, 2008). Winona described the seven value systems, which included spirituality. Zabrina focused on the soul of the leader, and the need for balance. Julie’s art focused on the spiritual need for positivity, deflecting the negative influences inherent in the physical world.

Evolution of Cultural Identities

Each of the visual representations was decidedly Native American in appearance, infused with symbolism, and colors and motifs steeped in traditional craftwork. Through discussions following the creation of their visual representations of leadership, all of the women expressed a firm identification in both Native American and Deaf communities. The evolution towards an identity that intersects both communities was not easy for participants, particularly since they did not have Native American Deaf women role models. Poston (1990) proposed that bi-racial (and in this particular context, bicultural) individuals go through five levels of identify formation: Personal identity (children who do not completely link to a specific racial or cultural group); Choice of group categorization (choosing to identify with a specific group based on factors that include appearance and background knowledge of culture); Enmeshment/denial (the experience of feeling guilt or shame at not being able to connect with all parts of one’s heritage, resulting in anger or frustration); Appreciation (through exposure to their heritages, one may choose to identify more with one group than another); and finally Integration (an individual begins to value all aspects of their cultural identities).

Cortelia appeared to integrate into both Native American and Deaf communities at an early age. This suggests strong environmental factors that encouraged her self-identity as a member of both groups. Zabrina experienced the most barriers in identity development, finding personal connection to the Native American and Deaf communities in adulthood. She has experienced several identity shifts throughout her journey to a community leadership role.

While Julie and Beulah were both born on reservations, each had limited knowledge of their Indigenous heritage and had to obtain this in adulthood. Both were able to gain some cultural knowledge through observations of traditional craft making within their tribes, and both chose to identify with the Deaf community until adulthood, later moving into appreciation and integration with their Native American identities.

Winona had a strong sense of her identity as a Native American, which was cemented through powwow participation. Accepting her identity as a Deaf individual was a slower process, particularly since she was mainstreamed in public school and did not interact with other Deaf individuals until college. Winona appeared to have minimal anger or guilt in relation to her identity formation. Access to college-level exploration enhances identity development among young adults who are from biracial/bicultural backgrounds (Renn, 2008).

Implications: Further Research and Policy Making

The original intent of this project was to explore the viewpoint of leadership through the lens of Native Americans who are Deaf and female. An interesting aspect of the project revealed that there are identity formation themes that can be further explored with future research. All of the women included their perspectives on how they arrived at their identity as members of two cultures that are distinct, yet held many similarities in terms of experiences of oppression and belief systems. Additional research is needed to investigate the issue of identity formation, particularly given the fact that none of the participants had other Native American, Deaf, female leaders to emulate while growing up.

The fact that at least three of the participants were born into tribal communities that were situated on reservations, yet did not understand the traditions and belief systems of their tribes until well into middle adulthood, emphasizes the need to ensure that communication access within tribes is available. Not all of the participants come from tribes that use visual-gestural languages, further compounding their ability to obtain information that is traditionally passed down orally from generation to generation, or from elders and clan mothers. Living part of their youth in residential schools for the deaf, a considerable distance from their tribal communities, they would not obtain indigenous knowledge from an educational system that is overseen predominantly by non-Indigenous professionals and classmates. These participants had to struggle to find information and understand it through observation only, and during limited periods of time when they were out of school on vacation.

Elders and tribal leaders oversee the welfare of their community, and there are many issues impacting Indigenous people today, from increasing violence committed on female members, often by non-Natives, to a variety of health issues that impact their tribal members such as the high prevalence of diabetes, substance abuse, and high suicide rates among their youth. Violations against their lands through destruction of natural environments by corporations are another issue tribes are dealing with. With all of these issues faced by tribal leaders, it is not surprising that the needs of a handful of tribal members who are Deaf may slip through the cracks.

Despite warring priorities, there is a responsibility to address the needs of this population. It is difficult to address them, however, with few resources or knowledge of how to provide support to tribal members who are Deaf. Leadership at residential schools for the Deaf are equally responsible for ensuring that all of their students’ needs are acknowledged and strategies are implemented that enrich the educational environment of their students.

As noted before, there is a connection between Deaf and Native American populations, based on shared historical oppression and the usage of visual-gestural languages. However, tribal leaders and their communities do not have in-depth knowledge of Deaf culture or American Sign Language, and because of the remote location of most reservations, there is difficulty finding a sign language interpreter willing to travel for several hours one way. Even if they were willing, most sign language interpreters are not knowledgeable about Native Americans in general, let alone each specific tribe’s mores, traditions, and ceremonies. Access to Native Americans who are sign language interpreters is very rare; to date, it is estimated there are a maximum of 25 interpreters who are Native American, and they are scattered all across the entire USA.

Educators, counselors, and other personnel are typically knowledgeable about ASL and accessibility, but do not know of, or understand, tribal perspectives. Policy implementation may help improve the experiences of these tribal members. In every state, Early Newborn Screening programs help identify hearing loss earlier. The purpose of this mandate is to ensure there is no delay in language development in Deaf children,

Policy implementation may help improve the experiences of Deaf tribal members. A policy that encourages shared resources among educators, counselors, and tribal leaders will increase the chances of that child becoming immersed in both cultures, and coming away with a stronger sense of identity. Educators in schools for the Deaf (particularly Native users of ASL who are also Deaf) could impart knowledge of ASL, Deaf culture, and technological resources. Tribal members could share valuable Indigenous artifacts, knowledge, and culture that these educators could use to reinforce Indigenous customs while the child is in school. One of the best examples of a school for the Deaf incorporating Indigenous culture would be the Kelston Deaf Centre in Auckland, New Zealand. In 1992, they constructed a Deaf marae (Maori communal meeting place) specifically to encourage Indigenous knowledge among their Maori students. To date, it is the only Deaf marae in the world.

None of the participants were exposed to Deaf Native American female role models during childhood and adolescence. Several participants remarked that this was a barrier for them; they had difficulty visualizing their own journeys without someone to look up to or emulate who were similar to them in terms of cross-cultural identity. It is suggested that schools for the Deaf and pertinent members of the tribe work together to develop programs that bring in mentors to encourage the indigenous knowledge of deaf tribal members. Such policy will go a long ways towards ensuring there are future role models for their indigenous, Deaf, and female members.

Concluding Remarks

The inclusion of art inquiry in an unstructured environment created a forum for the women in this study to express their identities as leaders in both Indigenous and Deaf communities. These women’s ways of knowing, as expressed artistically, further enriched the sharing of their experiences as individuals working through complex issues of identity in two cultures historically dominated by paternalistic, oppressive societal perspectives. By providing an opportunity for visually oriented communicators to express themselves in a visual format, participants were empowered to share their wisdom as Native American and Deaf women leaders.

References

Alford, D. (2002). Nurturing a faint call in the blood: A linguist encounters language of ancient America. ReVision, 25(2), 23-33.

Baker, S. (1996). The Native American Deaf experience: Cultural, linguistic, and educational perspectives. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Oklahoma State University, Oklahoma.

Barkdull, C. (2009). Exploring intersections of identity with Native American women leaders. Affilia, 24(2), 120-135. doi: 10.1177/0886109909331700

Baynton, D., Gannon, J.R., & Bergey J. L. (2007). Through Deaf eyes: A photographic history of an American community. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

Bird, S., Wiles, J., Okalik, L., Kilabuk, J., & Egleand, G. (2009). Methodological consideration of story telling in qualitative research involving Indigenous peoples. IHUPE—Global Health Promotion, 16(4), 16-27.

Child, B. (1998). Boarding school seasons: American Indian families, 1900-1940 (pp. 8-10). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Chin, J. L., Lott, B., Rice, J. K., & Sanchez-Hucles, J. (2007). Women and leadership: Transforming visions and diverse voices. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, LTD.

Dapice, A. (2006). The medicine wheel. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 17, 251-260.

Davis, J. E. (2011). Discourse in Native American Sign Language. In C. Roy (Ed.), Discourse in signed languages (pp. 179-217). Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

Davis, J. E., & McKay-Cody, M. (2010). Signed languages of American Indian communities: Considerations for interpreting work and research. In R. L. McKee & J. E. Davis (Eds.), Interpreting in multilingual, multicultural contexts (pp. 119-157). Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

Durr, P. (2006). De’VIA: Investingating Deaf visual art. Deaf Studies Today!, 2, 167-187.

Evans-Campbell, T., Walters, K. L., Pearson, C. R., & Campbell, C. D. (2012). Indian boarding school experience, substance use, and mental health among urban two-spirit American Indian/Alaska Natives. American Journal of Drug & Alcohol Abuse, 38(5), 421-427.

Farnell, B. (1995). Do you see what I mean? Plains Indian sign talk and the embodiment of action. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Fey, H. E., & McNickle, D. (1959). Indians and other Americans: Two ways of life meet. New York, NY: Harper & Brothers.

Finley, S. (2005). Arts-based inquiry: Performing revolutionary pedagogy. In N.K. Denzin & Y.S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research ( 3rd ed.) (pp. 682-684). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications...

Fitzgerald, T. (2010). Spaces in-between: Indigenous women leaders speak back to dominant discourses and practices in educational leadership. International Journal on Leadership in Education, 13(1), 93-105. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13603120903242923

Gallaudet Research Institute (2011). Regional and national summary report of data from the 2007-08 annual survey of deaf and hard of hearing children and youth. Retrieved from http://research.gallaudet.edu/Demographics/2008_National_Summary.pdf

Gannon, J. (1989). Deaf heritage: A narrative history of Deaf America. Silver Spring, MD: National Association of the Deaf.

Gone, J. P. (2011). The red road to wellness: Cultural reclamation in a Native First Nations community treatment center. American Journal of Community Psychology, 47, 187-202.

Holcomb, T. K. (2012). Introduction to American Deaf culture. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

Horovitz, E. G. (Ed). (2007). Visually speaking: Art therapy and the Deaf. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas Publisher.

Ladd, P. (2003). Understanding Deaf culture: In search of deafhood. Bristol, United Kingdom: Multilingual Matters.

Lajimodiere, D. K. (2011). Ogimah ikwe: Native women and their path to leadership. Wicazo Sa Review, 26(2), 57-82.

Lamar, C. C. (2010). Introduction: The art, gender, and community seminars. In C. C. Lamar, & S. F. Racette, with L. Evans (Eds.), Art in our lives: Native women artist in dialogue (pp.1-9). Santa Fe, NM: School for Advanced Research Press.

Leavy, P. (2009). Method meets art: Arts-based research practice. New York, NY: The Guildford Press.

McCabe, G. (2008). Mind, body, emotions and spirit: Reaching to the ancestors for healing. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 21(2), 143-152.

McLeod, M. (2002). Keeping the circle strong. Tribal College Journal, 13(4), 10-14.

Mihesuah, D. (2003). Indigenous American women: Decolonization, empowerment, activism (contemporary Indigenous issues).Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Miller, B. G. (1989). De’VIA (Deaf View/Image Art). Deaf way: Perspectives from the international conference on Deaf culture. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

Miller, K. (2004). Circle of unity: Pathways to improving outreach to American Indians and Alaska Natives who are deaf, deaf-blind and hard of hearing. Little Rock, AR: University of Arkansas.

Moore, M., & Levitan, L. (2003). For hearing people only (3rd ed.). Rochester, NY: MSM Productions.

Muller, H. J. (1998). American Indian women managers: Living in two worlds. Journal of Management Inquiry, 7(4), 4-28. doi: 10.1177/105649269871002

Napier, L. A. (1995). Educational profiles of nine gifted American Indian women and their own stories about wanting to lead. Roeper Review, 18(1), 1-16.

National Multicultural Interpreter Project (2000). Cultural and linguistic diversity series: Life experiences of Donnette Reins—American Indian—Muskogee Nation [Videotape]. El Paso, TX: El Paso Community College.

Neuman, L. K. (2006).Painting culture: Art and ethnography at a school for Native Americans. Ethnology, 45(3), 173-192. doi: 10.2307/20456593

Nomeland, M., & Nomeland, R. (2011). The Deaf community in America: History in the making. Jefferson, N.C.:McFarland & Company, Inc.

Padden, C., & Humphries, T. (1988). Deaf in America: Voices from a culture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Parasnis, I. (1998). Culture and language diversity and the Deaf experience. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Paris, D. G., & Drolsbaugh, M. (Eds.). (1999). Deaf esprit: Inspiration, humor and wisdom from the deaf community. Salem, OR: AGO Publications.

Paris, D. G., & Wood, S. K. (Eds.). (2002). Step into the circle: The heartbeat of American Indian, Alaska Native and First Nation’s Deaf communities. Salem, OR: AGO Publications.

Perdue, T. (1998). Cherokee women. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Pleis, J. R., & Lethbridge-Cejku, M. (2007). Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2006. Vital and Health Statistics, 10(235).

Poston, W. S. (1990). The biracial identity development model: A needed addition. Journal of Counseling and Development, 69, 152–155.

Portman, T., & Garret, M. (2005). Beloved women: Nurturing the sacred fire of leadership from an American Indian perspective. Journal of Counseling & Development, 83(3), 284-291.

Prindeville, D. (2000). Promoting a feminist policy agenda: Indigenous women leaders and closet feminism. The Social Science Journal, 37(4), 637-645. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0362-3319(00)00104-X

Prindeville, D. (2004). Feminist nations? A study of Native American women in southwestern tribal politics. Political Research Quarterly, 57(1), 101-112.

Renn, K. A. (2008). Research on biracial and multiracial identity development: Overview and synthesis. New Directions for Student Services, 2008(123), 13-21.

Shore, J. H., Orton, H., & Manson, S. M. (2009). Trauma-Related Nightmares among American Indian Veterans: Views from the Dream Catcher. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research: The Journal Of The National Center, 16(1), 25-38.

Sium, A., & Ritskes, E. (2013). Speaking truth to power: Indigenous storytelling as an act of living resistance. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 2(1), I-X.

Smoak, G. E. (2006). Ghost dances and identity: Prophetic religion and American Indian ethnogenesis in the nineteenth century (p. 153). Ewing, NJ: University of California Press.

Snively, G. J., & Williams, L. B. (2008). “Coming to know”: Weaving Aboriginal and Western science knowledge, language, and literacy into the science classroom. Educational Studies in Language and Literature, 8(1), 109-133.

Sonnenstrahl, D. M. (2002). Deaf artists in America: Colonial to contemporary. San Diego, CA: DawnSignPress.

Van Cleve, J. V. (Ed.). (1999). Deaf history unveiled: Interpretations from a new scholarship. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

Van Cleve, J. V., & Crouch, B. A. (1989). A place of their own: Creating the Deaf community in America. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

Ward, A. M. (2014). American Indian dance and music. Salem Press encyclopedia.

Weagal, D. (2007). Elucidating abstract concepts and complexity in Louise Erdrich's love medicine through metaphors of quilts and quilt making. American Indian Culture & Research Journal, 31(4), 79-95.

Weber, S. (2008). Visual images in research. In J. G. Knowles & A. L. Cole (Eds.), Handbook of the arts in qualitative research: Perspectives, methodologies, examples, and issues (pp. 41-54). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Winefield, R. (1987). Never the twain shall meet: The communications debate. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

________________________

*Pseudonym