Possibilities for Students At-Risk: Schools as Sites for Personal Transformation

Brenda J. McMahon

University of North Carolina at Charlotte

There is ongoing interest in educational theory and practice about student risk and student resilience (Barr & Parrett, 2001; Downey, 2008; Goldstein & Brooks, 2006; McMahon, 2007, 2015; Norman, 2000; Taylor & Thomas, 2001). Although resilience is almost exclusively associated with risk (Kaplan, 2006), the phenomena of being at-risk or being resilient are typically examined in isolation from each other. Change from being at-risk to resilient is largely expressed in behavioural language or strictly in terms of an individual’s relationship to an educational institution. At the same time, despite a body of literature that identifies education as transformational (Mezirow, 1995; Taylor, 2008), extensive searches of educational literature reveal an absence of research in the realm of the personal, social, and emotional transformations that adolescents and adults who are at risk experience as they develop resilience and shift from disengagement to engagement, and/or academic failure to success in schools.

This paper, which is part of a larger qualitative study (McMahon, 2004), addresses these gaps in educational research by articulating connections between educational resilience research and change theories, and by utilizing these bodies of scholarship to propose a theory of personal transformation. The initial study consisted of interviews with university students who had either not graduated from high schools or who had completed high school without credits required for university admission. That study examined concepts of student engagement, resilience, and personal transformations. For the purposes of this paper, I first provide an overview of relevant literature on resilience and identity as related to change, transition, and transformation. Secondly, I present data from participants’ narratives of emotional and social journeys from being at academic risk in high schools to being academically successful in universities academic experiences. Thirdly, I use the Mobius strip as a metaphor to hypothesize a theory of transformation as a means of understanding these students’ personal transformations. Finally, I identify key issues for educators to consider in the creation and maintenance of inclusionary school environments that foster growth and transformation and make recommendations for further research.

Review of Literature

This section provides a brief overview of literature describing resilience factors and processes, personal identity, change, transition, and transformation.

Resilience

In order to understand how some people overcome, or succeed despite apparent risk factors and processes, educational researchers and theorists have identified either protective factors and processes or proximal and distal factors (Celik, Cetin, & Tutkun, 2015) that are integral to resilience. Some theorists (Barr & Parrett, 2001; Kaplan, 2006; Taylor & Thomas, 2001) emphasize the significance of protective factors, formulated as internal attributes of individuals while other scholars (McMahon, 2007; Norman, 2000; Rennie & Dolan, 2010) focus on protective processes, envisioned as existing within and across relationships. Although not mutually exclusive, both perspectives conceive of resilience as mechanisms that “ameliorate” or “buffer” a “person’s reaction to a situation that in ordinary circumstances leads to maladaptive outcomes” (Taylor & Thomas, 2001, p. 9). Researchers (Barr & Parrett; 2001; Celik et al., 2015; Norman, 2000; Smokowski, Reynolds, & Berzuczko, 1999) identify personal attributes differentiating children who are resilient from their peers who remain at risk. These include an absence of organic deficits, an easy temperament combined with increased responsiveness, adaptability, an internal locus of control, a positive outlook, a social competency, an ability to solve problems, a sense of autonomy, a sense of purpose, and a sense of humour. For adolescents and adults who are members of minoritized communities, positive ethnic identity affirmation is an essential component of resilience (Garrett et al., 2014; Williams, Aiyer, Durkee, & Tolan, 2014). Protective factors are often seen as indicative of an individual’s agency and essential to facilitate the process of overcoming adversity.

In addition to individual attributes, resilience is also defined as existing in interpersonal dynamics; specifically, student resilience is fostered by support from family members, peers, educators, schools, as well as social and community organizations. For example, parents’ high expectations pressure students to remain in school and work toward high achievement (McMillan & Reed, 1994). Along with family, Johnson (1997) highlights the significance of school and community "as potentially protecting students from risk factors or as potentially compensating for personal and social disadvantage” (p. 45). Westfall and Pisapia (1994) claim that the existence of support systems at home, school, and the community engender “the development of constructive personality traits such as self-efficacy, goals orientation, optimism, internal expectations, personal responsibility, and coping ability” (p. 4). In keeping with efforts to understand resilience processes, Pianta and Walsh (1998) also maintain, “resiliency is produced by the interactions among a child, family, peers, school, and community” (p. 411). They caution against the dangers of “locating the successes of children in one (or even two or three) of these places [child, family, school], in the absence of an emphasis on the interactions, transactions, and relationships among these places” (p. 410). As an arena wherein relationships among individuals, groups, and systems occur, schools have a significant role to play in creating environments conducive to resilience (Bethea & Robinson, 2007). Benard (1995) contends that “reciprocal caring, respectful, and participatory relationships are the critical determining factors in…whether a youth feels he or she has a place in this society” (p. 3). Similarly, Smokowski, Reynolds, and Bezruczko (1998) find that the “relational bonds” between teachers and resilient adolescents were important in buffering risks and facilitating adaptive development. Schools as sites of resilience include colleges and universities (Walker, Gleaves, & Gray, 2006) where resilience is seen as important for student success.

The concepts of risk and resilience and of personal identity can be further examined through scholarship regarding vulnerability, adaptation, and agency. From an ecological perspective, Adger (2006) describes vulnerability, or risk, as a mechanism to describe “states of susceptibility to harm, powerlessness, and marginality…and for guiding normative analysis of actions to enhance well-being through reduction of risk (p. 268). Resilience factors and processes can be understood as adaptation or agency. Nelson, Adger, and Brown (2007) identify adaptation as “concerned with actors, actions, and agency and is recognized…as an ongoing process” (p. 398). They further claim that instead of focusing on reducing vulnerabilities associated with risk, “a resilience approach recognizes that vulnerabilities are an inherent part of any system. Thus, rather than trying to eliminate vulnerability, the challenges are to identify acceptable levels of vulnerability and to maintain the ability to respond when vulnerable areas are disturbed” (Nelson, Adger, & Brown, 2007, p. 412). An ecological or systems approach to resilience conceives agency as operating at individual, organizational, and system levels. As individuals, Bandura (2000) states, “people are partly the products of their environments, but by selecting, creating, and transforming their environmental circumstances they are producers of environments as well. This agentic capability enables them to shape the course of events” (p. 75). Agentic, as defined by Lester (2004), “is a force expressing itself, rather than a pawn of other forces” (p. 94). Because individuals live their lives in community with others, at institutional and systemic levels, forms of agency also include proxy agency, as when others work as advocates on behalf of individuals, and collective agency, whereby individuals work in a community to create change (Bandura, 2000). These agentic forces work in concert so that individual resilience factors and organizational resilience processes co-exist in order to reduce risk and adapt to conditions of vulnerability.

Identity

Personal identity has complex intrapersonal and interpersonal dimensions. Kroger (2000) contends that “identities are formed through the mutual regulation of society with individual biology and psychology; thus the range of variation in the identities that will be sanctioned and fostered lies in the hands of the culture itself” (p. 66). Consistent with the concept of resilience processes, critical identity theorists (Kelly, 1997; Hemmings, 1998, Widdershoven, 1994) emphasize the impact of external social forces on identity formation. While not negating the significance of personal agency, and consequently resilience factors, Kelly (1997) claims that identities “are not forged through personal and psychic claims only; and…are never formulated outside the political dynamics of the social and the symbolic that mediate all signifying claims” (p. 108). As a precursor of these ideologies, theorist Vygotsky (Eggen & Kauchak, 2001) adopted a socio-cultural approach to education that emphasized the role of social influences on children’s cognitive development. He maintained that interactions with others form the basis for development, as dependent on the influence of external social environments as it is on internal processes. In keeping with the situational nature of resilience processes, Agnew (1996) claims that “the perception of who one is and of one’s location vis-à-vis other social groups can change in different contexts” (pp. 62 – 63). Students’ identities as learners are shaped by interactions with educators and other students and some schools and classrooms are conducive to resilience building for students at risk while others are not. As Rosenthal and Jacobson (1968) demonstrated, teachers’ beliefs about students’ capabilities become self-fulfilling prophecies and students can become the learners teachers anticipate.

Similar to notions of identity, conceptions of change and development have various meanings. However, “unlike identity, in which the core of the concept concerns sameness, the essence of development is change” (Grotevant, Bosma, de Levita, & Graafsma, 1994, p. 15). Theorists (Brammer, 1991; Bridges, 2001; Jick, 1993a & b) differentiate between kinds of change. Developmental change is change in its most superficial form. Transitions are deeper than developmental changes and involve letting go of identities and the beginnings of a redefinition of self and transformational change occurring at the deepest level.

Change

Developmental change is seen as growth as in “the improvement of a skill, method or condition” or the ability to “‘do better than’ or to ‘do more of’ what already exists” (Jick, 1993a, p. 2). This happens in schools as students understand new concepts and develop skills. Developmental change theory adaptation and growth can be seen as an actualization tendency (Kegan, 2000). Change in this sense suggests adaptation and modification to existing internal and external conditions such as when students adapt their behaviours to policies and practices in schools. Anderson and Hayes (1996) extend the temporal dimension of development, reporting that identity development is a continuous process throughout adulthood and that “new sources of self-esteem are found through a reappraisal process that highlights areas of one’s life that have yet to be fulfilled or have changed in personal meaning” (p. 23). Although expressed in developmental terms, unlike child development theories, which imply definable, linear, age-related progression, literature examining adult developmental change “suggests movement and fluidity, a back-and-forth motion that may be best observed in general as opposed to trying to capture change in age-specific categories” (Anderson & Hayes, 1996, p. 8). For adults, in particular, changes do not occur within a prefixed timetable. While changes may entail situational shifts, they do not require alterations in perceptions or beliefs and for many adults in university, change occurs without concurrent fundamental paradigm shifts. Kegan (2000) suggests that it is possible for “changes in one’s fund of knowledge, one’s confidence as a learner, one’s self-perception as a learner, one’s motives in learning, one’s self-esteem…to take place without any transformation because they occur within the existing frame of reference” (pp. 50 – 51). However, shifting to a new frame of reference is indicative of either a transition or a transformation as opposed to a developmental change.

Transition

The distinction between change and transition, according to Bridges (2001), is that “change can happen at any time, but transition comes along when one chapter of your life is over and another is waiting in the wings to make its entrance” (p. 16). Examples of this in education could be moving from high school to college or university. Bridges (2001) maintains that “transition invokes the psychological dimension of change,” and “even the prospect of change can put us into transition,” and “the change itself may immediately go from old to new…transition always makes us spend a surprising amount of time in that uncomfortable in-between neutral zone” (p. 3). The resulting qualitative changes in identity only take place if development as adaptation is no longer feasible. In this case, a person’s “identity may be expected to be disequilibrated and to undergo an accommodative process when it can no longer assimilate successfully new life experiences” (Marcia, 1994, p. 71). Transitions may occur if students move from small homogeneous high schools to large, racially, culturally, and experientially diverse universities.

Change theorists (Brammer, 1991, Bridges, 2001, Frankel, 1998) describe the instability of transitions. Even those that are self-initiated and seen by the individuals as positive are accompanied by feelings of grief and loss, which is a by-product of letting “go of our old outlook, our old reality, our old values, our old self-image” (Bridges, 2001, p. 5). Quoting Scott, Frankel (1998) reports that during “transitions, there are times of unusual suspension, loneliness, [a] sense of being vaguely out of joint, [a] heightened sensitivity to pain and loss, [and] symptoms of grief” (p. 83). These emotional discomforts are some of the reasons that individuals resist transitional changes, “not because we can’t accept change, but because we can’t accept letting go of that piece of ourselves that we have to give up when or because the situation has changed” (Bridges, 2001, p. 3). By focusing on the need for transformation, and by developing resilience coping mechanisms such as acquiring a positive outlook, problem solving, support building, and managing stress, individuals are able to navigate transitions successfully. According to Bridges’ (2001) archetype, this transition involves not only new attitudes and self-images, but also it entails “a new sense of ourselves, a new outlook, and a new sense of purpose and possibility” (p. 6). Similarly, Brammer (1991) sees “experiencing a paradigm shift” (p. 8) as an outcome of undergoing transition that could occur because of a shift from academic failure to academic achievement. In order to navigate transitions successfully, these theorists claim that individuals must overcome the difficult challenges involved in letting go of the past. This is what distinguishes changes from transitions. The distinction between transitions and transformations is more difficult to delineate clearly, since they are different in degree rather than in kind.

Transformation

While developmental change may be part of both transition and transformation, the reverse is not necessarily the case. With reference to education, Kegan (2000) supports a distinction between change and transformation by highlighting the dissimilarity “between assimilated processes, in which new experience is shaped to conform to existing knowledge structures and accommodative processes, in which the structures themselves change in response to new experiences” (Kegan, 2000, p. 47). The former is change while the latter is either transition or transformation. The depth of transformation is evident in that “we do not only change our meanings [but also,] we change the very form by which we are making our meanings” (Kegan, 2000, p. 53). What distinguishes personal transformation from change and transition is a complicated process involving cognitive, behavioural, emotional, and social dimensions that have practical consequences for the way individuals interact on intra- and interpersonal levels.

Change theorists (Brammer, 1991; Bridges, 2001; Porter, 1999; Prochaska, DiClemente, & Norcross, 1992) have attempted to delineate this process. The models they developed are important in that they recognize the agency of the person who is changing as well as the visible, external, and behavioural components, and the invisible, internal, and motivational components involved in change processes. As opposed to linear change models, these paradigms propose a gradual spiral through stages, which, although fixed, present the time spent in each and the direction of movement as individual phenomenon. Brammer (1991) speaks of envisioning life, not as a lifeline or circle but as cyclical, proceeding “like a spiral; thus events tend to repeat implying that if this opportunity is not grasped another one will come along in due time” (p. 11). Movement from one stage to another is nonlinear, ambivalent, and individual and may be based on either a desire to move to another stage, or resistance when there is a lack of cohesion between the changer and the current stage (Prochaska et al., 1992; Porter, 1999). The strength of these models is that they focus on the individual and his or her agency in undergoing transitions. This is also their limitation. While they do acknowledge that there may be triggers in the environment that lead to the initiation of transformational processes or that these may be instituted in response to external factors, they ignore ongoing interactions between the individual and his or her social environments. With the individual as their sole focus they fail to explicitly recognize either the multiple identities which constitute and are constituted by the “locatedness” of the individual, or the relevant external enhancers and inhibitors involved in this process.

Methodology

Data were gathered from semi-structured interviews with students currently experiencing academic success in two universities who previously experienced academic failure in high schools. Focusing on the students’ accounts of their experiences addresses concerns raised by Gitlin and Russell (1994) who observe that traditional academic institutions use a dominant perspective of knowledge and knowledge creation that "helps create a great divide between those who regularly produce specialized forms of knowledge and those who are supposed to be informed by that knowledge" (p. 184). Furthermore, even though there is an abundance of research conducted on schooling in North America, Seidman (1998) makes a valid contention that in educational contexts, "little of it is based on studies involving the perspective of students [etc.]...whose individual and collective experience constitutes schooling" (p. 4). As a means of filling this gap, the focus on students' perspectives in this study is also in keeping with Norum's (2004) suggestion that narrative inquiry, as a form of qualitative research, "creates a space for and values personal voice and the sharing of personal perspectives . . . people's stories are brought to the forefront and become the data" (p. 4). To understand their stories, participants were asked questions about their experiences with academic failure and success; personal, social and educational factors and events that impacted their academic achievement; personal, emotional, cognitive, and behavioural changes concurrent with or following changes in academic status; and changes in interpersonal relationships with friends, family, community members, and educators concurrent with or following changes in academic status.

Purposive sampling and snowballing techniques (Merriam, 1998) were used in the selection of participants for this study. University transitional and bridging program1 were contacted and they sent information to their graduates who were enrolled in universities. Interested participants contacted me as a result and some participants referred others for the study. The interviews were created and administered according to university human subjects’ protocols. Pseudonyms were used, and subject confidentiality was maintained so that only participants in the study could accurately identify their contributions. I personally transcribed the data and the participants were provided with the opportunity to review, edit, and add to transcript data. Consistent with Creswell’s (2009) systematic process for coding data, I read the transcripts multiple times individually and in groups, first to gain a global sense of the data and then to divide responses into sections. Overarching codes relevant to resilience and transformation were derived from the interview questions. Specific codes within these larger categories became apparent from the interview data. I revisited the data to check for accuracy, and the themes were critically analyzed to ensure that they authentically represented the phenomenon. I integrated the sections, analyzed statements, and categorized them into clusters of emerging themes.

Findings

Although in terms of their current university academic achievements, the respondents who were the focus of this study could be considered an elite sample, from other perspectives this was not the case. The participants consist of two Black females (Deanna, Elaine), one Black male (Anthony), two White males (Frank, Greg), and three White females (Barbara, Carol, Jennifer). All but two (Barbara, Greg) grew up in single parent households, all except one (Greg) grew up in families with low socio-economic status, and three (Barbara, Frank, Jennifer) did not graduate from high school. Those who completed high school had been streamed into non-academic programs that did not prepare them for post-secondary, formal education.

All of the respondents identified intra- and interpersonal transformations they have experienced as a result of, or at least concurrent with, changes in their academic achievements. All the participants referred to increases in their self-esteem, growth in self-sufficiency, and developments in the attainability of goals, some of which is a result of newfound beliefs in their abilities. Changes in their feelings about themselves, other people, and the larger world were expressed with both elation and trepidation. All of the participants articulated experiencing changes in relationships with a family member and/or friends. While all described their journeys as positive, forward-moving, growth experiences, they also referred to external and internal impediments to, and feelings of loss experienced during, their change processes. Analysis of the data revealed three distinct phases of change and transformation. However, their responses suggested that the type or level of change was dependent on the length of time and degree to which they would have been considered at risk, or the extent to which their lived experiences and identities were (in)compatible with their previous educational institutions. For example, although Greg recounts his transformative experiences, his background as a White middle-class male with two parents in professional occupations meant that even when he was not succeeding academically, he did not envision himself as not belonging in academic settings, his effort, and not his ability, having been questioned. Conversely, in order to undergo their transformations, participants who were members of marginalized racial and economic communities such as Anthony, Barbara, Deanna, and Elaine who had received negative judgements about their academic abilities, had to re-envision themselves as academically capable.

Dissatisfaction

For participants in this study, the first phase of their transformations was characterized by dissatisfaction, disengagement, and alienation from educational institutions that began in elementary and/or secondary school and lasted throughout the period when they would have been characterized as at risk. Their narratives identified factors related to school personnel and curriculum that created risk. For example, Elaine recalled that her Grade 9 principal stigmatized her. “He knew the area I was coming from and I think he believed because everyone else failed…‘You’re supposed to not want anything’” (Elaine, interview, September 2003). This was similar to Carol’s Grade 9 experience when she said, “I don’t know if anyone even paid attention, but I went to half of Grade 9 and dropped out and worked full-time” (interview, October 2003). Of teachers and administrators she suggested, “They could have noticed that I wasn’t showing up and even pulled me aside and say you know, you haven’t been here for two weeks and now you show up today, what’s going on?” (Carol, interview, October 2003) This educational faculty disinterest was echoed by Deanna, who says that in high school, “I had one teacher who would show up to class… you could smell alcohol on him and it was so obvious that the teachers knew—the whole school knew and there’s no way for them not to know” (interview, September, 2003).

Anthony recalled his early high school encounters with school personnel as decidedly negative: “I felt like I was always targeted especially by vice-principals, principals, and teachers. They perceived me in certain ways.” This was magnified by external societal hegemonic structures, “It’s everyday, day-to-day people and how they treat young, especially young Black adolescents are the most targeted. To be young Black and 16, you are a target, 24 hours a day, seven days a week” (Anthony, interview, September 2003). This lack of caring was not limited to students such as Deanna and Anthony who were persistently marginalized by educators. Jennifer also experienced the callousness when an upheaval in her home life had repercussions for her academic performance. Her feelings about this were evident when she said, “If you see a kid going from honour roll down to 30%, you would think that they would notice something and nobody, counsellors, nobody did anything” (Jennifer, interview, October, 2003).

Instead of being equitable sites that mitigate risk, schools further exacerbated Anthony’s alienation through meaningless and irrelevant curriculum. Rather than token references to American Black athletes as possible role models, he said, “It would have made me feel that I could be part of the system knowing that there were other Black professionals who were part of the system and they struggled and they’re there now and they survived and they did it all. I never had that” (Anthony, interview, September 2003). Similarly, Frank speculated that one reason he quit school in Grade 10 was that “everything in school just seemed irrelevant. I never saw myself going on to university and so I thought, ‘why do I have to know any of this?’” (interview, September 2003). Although he saw himself reflected in the curriculum, Greg blamed rote practices and disinterested teachers whose approach was “very dry” and who would tell students to “just do your work” for contributing to his disengagement from school.

The participants’ narratives revealed the existence of a period during which their dissatisfaction with aspects of their lives was augmented by an understanding that they had the power to choose between differing options and to act on those choices. In Anthony’s words, “Students … need to know of all their options because when you think you can only do one thing you neglect exploring other things that you can get into and do” (interview, September, 2003). The participants referred to their initial awareness of these choices as originating from knowing what they did not want to do. For Barbara this was “a real desire to not do anything that was day to day” (interview October 2003). Similarly, Carol spoke of her desire for a different life than the one she was living.

I was just sort of sick of—sick of living, trying to pay my rent on tips and—just so fed up with it and just not getting any further. I would never have gotten a job that paid me any more than $15,000 – $18,000 a year. (Carol, interview, October 2003)

Deanna was also employed in the service sector. According to her, “I was at a clothing store…It wasn’t a pleasant environment and I’m not a fake person and I found it very difficult to be fake every day and push my fakeness on people. So I didn’t do well” (Deanna, interview, September 2003). In keeping with this theme, Elaine said, “I wanted an education…I wanted good things in life. I didn’t want to become like a lot of the people in my area; trapped, poor and with little hope” (interview, September 2003). Anthony recalled the impetus that provoked his shift from this phase. “I feel that what saved me was that I was 19 and thought to myself ‘I’m going nowhere and I’m just going to be another statistic. Another young Black person who is not educated, who doesn’t have a diploma’” (Anthony, interview, September 2003).

Cohesion

The second phase of the participants’ journey was characterized by the excitement and energy associated with connecting institutional learning with their indigenous knowledge. Anthony stated, “I just love knowledge. I like to learn. Especially being within this environment that I am right now there are so many things” (interview, September, 2003). Likewise, Barbara reflected, “I loved the books we were being asked to read and I wanted to talk about them and I wanted to be involved” (interview, October 2003). Carol recalled that one of the things she most enjoys about university is “the actual things we talk about in that class and what I learn in that class. I think I actually apply them to my life” (interview October 2003). While the participants were overwhelmingly positive about this experience, they also experienced it as conflicted as they made connections between politics, power, and privilege. Jennifer and Anthony summarized these feelings. Jennifer located her anger arising from her increased awareness within the learning environment as she reflects, “Sometimes I’d get mad as hell at a professor but they brought the best out in me. They forced me to do well” (interview, October 2003). Furthermore, Anthony emphasized inequities generated by larger societal forces, “Sometimes what you learn really pisses you off… it’s politics and economics and you have to deal with it and learn as much as you can and just go with it” (interview, September 2003).

In addition to meaningful curriculum, educational personnel provided support during this phase. Contrary to her earlier experiences with inauthentic and uncaring educators, Deanna says, “Everyone seems real there. They seem genuine and seem aware like, if you come to them and say, I’m going through a lot of difficulties because of this, they’re like, okay, we understand, you’re not the first” (interview, September, 2003). This level of compassion was juxtaposed with high expectations. Barbara expresses admiration for one professor, “He was so helpful; he was so kind and considerate and gracious. I was just so grateful for people like him who saw something in me and had faith in me and it was people like him who made me think I could do this” (interview, October, 2003). Similarly, says Frank, “I would go to some professors after class and meet with them and I became really engaged in the papers that I wrote.” Beyond this, “the teachers, [the] faculty there were really supportive and helped a lot but for me it was even bigger with having a lot of other comrades who... felt the same way” (interview, September, 2003). Likewise, Anthony described his experience with educators who supported him, “It seemed like there was a strong community of teachers… Most important of all, everyone treated me with respect” (interview, September 2003). The participants configured respect from educators as constituted by high expectations and autonomy. Greg summarized their attitude with “they would talk to you one-on-one and point out what it was that you weren’t doing well without making it sound like they were making you change. They left the decisions and responsibility to the student, which pushed people to do better” (interview, September, 2003). The respondents’ recollections of interactions with educators and educational institutions assumed absolute dimensions. The extremes of non-supportive teachers and schools were replaced by compassionate and engaging relationships with faculty and institutions without reference to any small steps in between.

Concurrent with their academic progress, they referred to growth in external familial and social supports. This was exemplified in Anthony recollection of his mother’s earlier “nonchalant” attitude toward his returns to high school that changed dramatically by the time he graduated from the transitional program. This is the point at which he recalled, “I started to get lots of love and support” (Anthony, interview, September, 2003). Again, the lines between the primacy of internal and external factors and processes were blurred as the participants spoke of increases to their perseverance and esteem in conjunction with positive support and relationships within and outside of educational institutions. For example, Deanna said of herself, “I adjust according to wherever I am … I did what I had to do” (interview, September 2003). She also stated that concurrent with her success in university, I have “become more self-assured, more self-aware, self-love – all that positive stuff … and I’ve become less angry, less judgmental – less of all the negative things and more of all the positive” (interview, September 2003). This optimistic outlook was echoed by Elaine’s claims that success in school “gave me a lot of confidence. It gave me a lot of willpower. It let me know that I could do anything I really want to do and if I’m doing it for myself it makes it a million times better” (interview, September, 2003). Greg’s experience is similar as he indicated, “I think I feel a lot better about myself… I’m a lot more motivated now and happy about my life than I would have been before” (interview, September 2003). As well, Carol linked her increased confidence within academic spheres with other aspects of her life. She credited her accomplishments as giving her “self worth probably more than anything. I just will not even engage with someone that even wants to put me down” (interview, October, 2003). Further to this, Jennifer disclosed, “I have better faith in people. I think my attitude has changed. People aren’t so bad…There are some people in the educational system that do care” (interview, October 2003).

Regrouping

There was evidence of a third phase in the participants’ narratives of their personal transformations. The interviewees all provided examples of times they needed to regroup as they struggled with their identities as successful students that highlighted the non-linear nature of their journeys. Carol and Jennifer returned to and left high school several times before their admissions to their bridging program. According to Jennifer, “Coming back to school was so hard, there were some days I just wanted to give up and go back to getting my old job back” (interview, October 2003). Elaine’s narrative emphasized the dichotomy inherent in being Black and academically successful. As she recalled:

It has to do with how people looked at me, not just what I did but what people expected of me. Although I identify myself as a Black student, some people say, “You know, you’re not. You could be something else if you want. You could say you’re something else if you want.” I guess some teachers didn’t know I was Black although I don’t know how you couldn’t know and I think that shapes a lot. I don’t think they thought I could be something other than Black. I think they thought I should want to be something other than Black. So of things I could chose to identify myself as, why would you chose to identify yourself as Black? That is the experience I have. Black is less than. It should be the least of your choices so if you could choose something better than Black why not choose to be something better? (Elaine, interview, September 2003)

Another aspect of the iterative nature of their transformation processes was evident as the participants made discoveries about the limitations of their programs that resulted in another phase of Dissatisfaction. As Deanna described it:

You’re told, ‘Oh you’re going to go to university. They’re going to welcome you … you’re just a new budding mind, and then you get there and they want you out. They’re going to do their best to weed you out. (interview, December 2003)

Jennifer articulated a similar experience in moving from the college to the university at large: “This is a totally different atmosphere, and I never thought I would say that. I thought university was the be all and end all. It is great but you’re just a number” (interview, January 2004). Additionally, three of the participants contacted me after the interviews were completed to report that the university programs they were successful in led to degrees that did not allow them to enter teacher preparation programs, even in the universities granting these degrees. They expressed feelings of betrayal and frustration that institutions were once again erecting barriers to the fulfillment of their career goals and spoke of a desire to circumvent these obstacles.

Discussion

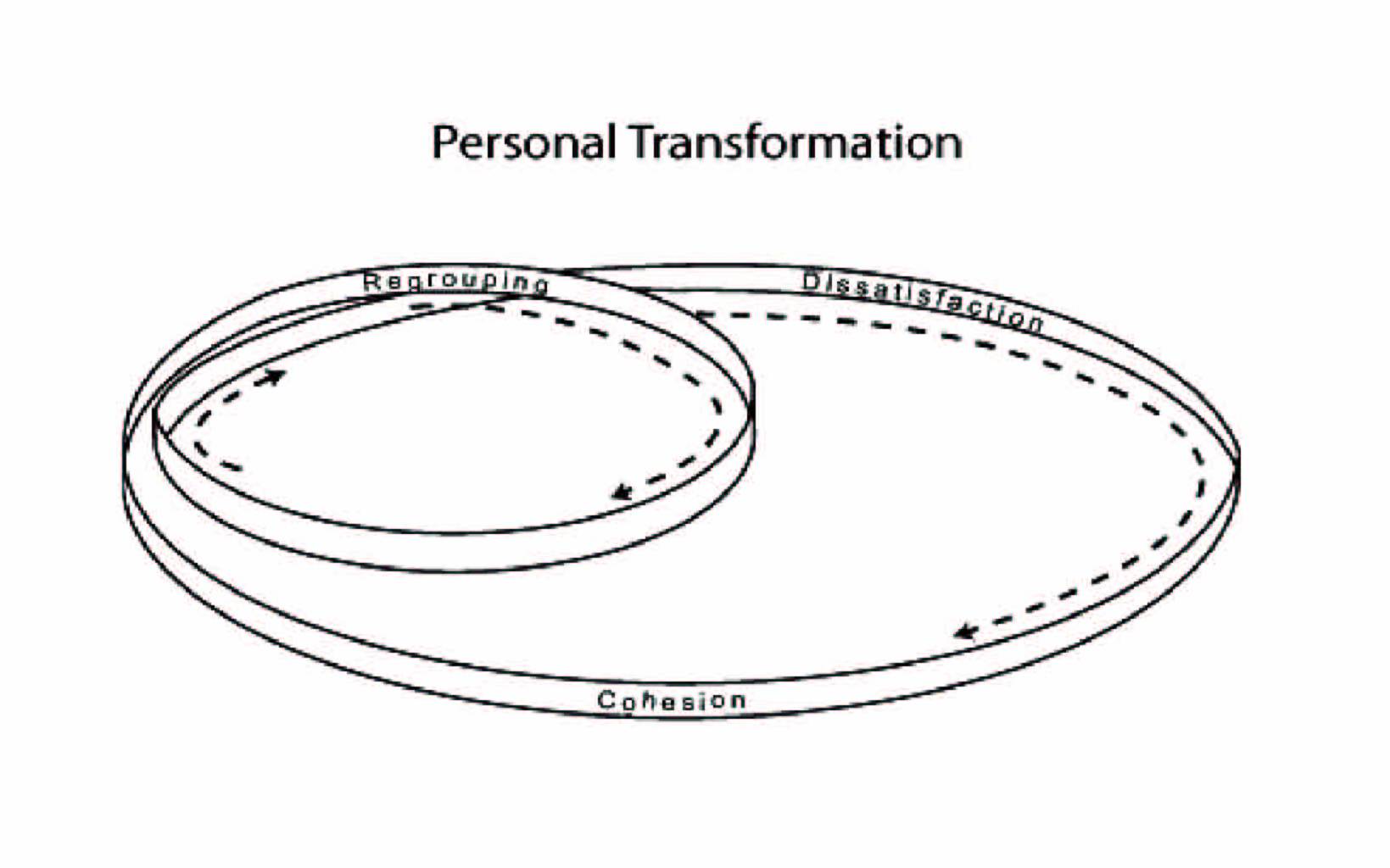

The image that emerged from the data to symbolize the participants’ ongoing transformational processes is that of a Mobius strip. This unending, one-edged circle with its illusion that what appears to be internal is external and vice-versa is consistent with a transactional and transformative notion of resilience (Elias, Parker, & Rosenblatt, 2006; Luthans, Vogelgesang, & Lester, 2006). Resilience from this perspective emphasizes the interconnectedness of the individual and the environment over time to the extent that it becomes difficult to distinguish between the impact of the individual’s changes to his or her ability to overcome hardships and the environmental conditions that enable them to thrive. Both aspects are necessary and perhaps, in isolation, not sufficient for the development of resilience and the interviewees’ transformations. Just as educators’ views about participants’ deficiencies in academic capacity had become negative self-fulfilling prophesies in high schools, externally generated high expectations became internalized positive self-fulfilling prophesies as they experienced success in university courses. Concurrent with the internalization of external expectations, as the students develop stronger academic identities, others experience and treat them differently.

In addition, the Mobius strip illustrates the complex relationship between identity as encompassing sameness and identity as constituted by change. Within this paradigm, change is continuous and individuals’ identities exist internally and are influenced by families, peers, schools, and communities. Changes as transitions and transformations can be seen to result from the tensions inherent in moving through overlapping iterative phases, which, although containing aspects of models outlined in the Review of Literature—the phases of Dissatisfaction, Cohesion, and Regrouping—depict the processes that these marginalized individuals experienced as they struggle to develop efficacy within hegemonic structures. Movement from one phase to the next was more likely a result of cumulative issues rather than one singular event.

Figure 1. Personal transformation

The image of the Mobius strip, with its retrograde motion as a means understanding the participants’ narratives is consistent with earlier research by Gilligan (1982), who identified the importance of disequilibrium and movement between phases and in women’s moral decision making. In a similar vein, the interviewees in this study refer to feelings of dissonance as instrumental to their personal transitions and transformations. In some sense, these phases occur simultaneously, since no one is in one place in all aspects of their personal social and academic lives. Changes from one phase to another occurred when either disequilibrium or equilibrium in one or more significant facets of their lives built to a point where the need for change outweighed remaining in the current phase.

Dissatisfaction

The participants’ descriptions of themselves and their experiences throughout the Dissatisfaction Phase is demonstrative of the literature regarding students at risk that examines compounding effects of individual, family, community, and school factors. Risk factors for students that affect their vision of education as a means of achieving success that were identified by the interviewees include living in poverty, membership in a minority race or ethnic group, single-parent family composition, and parents’ low level of education (Barr & Parrett, 2001; Peart & Campbell, 1999). Policies and practices in schools that exacerbate risk and, consequently, dissatisfaction with educational institutions as sites were they could thrive were identified as irrelevant and meaningless curriculum, absence of authentically caring educators, lack of respect from teachers and administrators, and low and negative expectations by educators and the students themselves (Burney & Beilke, 2008; Garcia & Guerra, 2004). The participants were cognizant of the compounding impacts of internal and external sources of dissonance. Participants described a vision for their lives, which they formerly believed only existed for other people; they also believed they could achieve lives that differed from their current experiences, and they began taking steps toward achieving these multiple times. For example, although neither Barbara nor Jennifer completed high school after repeated attempts to do so, Anthony recalled that before he finally earned his secondary school graduation diploma, “I went from school to school, semester to semester. It was kind of sad because I committed to school for a month and then I would just drop out” (interview, January 2004).

The participants were able to move out of the Dissatisfaction Phase when external factors coincided with and supported their internal desire to complete secondary and post secondary schooling. Carol claimed that her return to school was made possible by economic assistance. “I know that sounds rotten to say but it’s because they promised me that I would be financially okay if I decided to drop everything and come back to school” (interview, October, 2003). Deanne encountered a teacher who told her about the transitional program that enabled her to attend university despite receiving very low grades in high school. For Elaine the key was supportive faculty. “They encouraged me to come to school. They noticed me and said, ‘You’re 18 years old and have 3 credits so it’s going to be an uphill climb’” (interview, September 2003). Efforts representing initial short-term forays into the Cohesion Phase were sustained when supported and maintained through increased coherence between personal, social, and institutional initiatives. The move to Cohesion happened when they were able to envision and sustain a different and better existence for themselves.

Cohesion

During the Cohesion Phase, individuals took action toward the achievement of their self-selected goals that cohered with institutional and/or social group supportive behaviours. Dissonance was reduced and individuals felt a greater sense of internal and external synchronicity. Similar to the Dissatisfaction Phase, the Cohesion Phase appeared to exist within a continuum, with some aspects of the participants’ lives more synchronized than other aspects, rather than as an absolute shift within all intra- and interpersonal dimensions. Internally the Cohesion Phase was characterized by increases in self-esteem and self-efficacy, receptivity and reflexivity. Interpersonally, this phase exemplifies positive changes in relationships with families and friends, and in interactions with educators and educational institutions. Actions, behaviours, and attitudes that the participants enacted during this phase, as well as the external influences that support it, align with factors and processes identified in the resilience literature (Barr & Parrett, 2001; McMahon, 2007; Norman, 2000; Taylor & Thomas, 2001). Consistent with Action and Maintenance Stages described by Prochaska et al. (1992) and Porter (1999), respondents spoke of the need to remain focused on their goal and sustain their efforts. Although these change theorists focus solely on individual agency, this phase entailed not only the internal, individual actions of, as Carol expressed it, “Just getting out of bed every morning.” It also required supportive relations with educators, the ability to access and find support from external resources, and for students such as Anthony and Elaine, the racial identity affirmation identified by Williams et al. (2014) as important for resilience, was realized as they saw themselves in the curriculum and as Black academics. The ability to move toward their goals, for each of the participants, was a result of coherence within the intersections of increased confidence in their abilities and supportive environmental factors, including family, friends, and educators.

This sense of equilibrium was disrupted by internal or external forces, initiating a move to the Regrouping Phase. The Cohesion Phase ended when either these support systems were no longer synchronized or the participants themselves lost their focus. Deanna referred to a disparity she experienced between the articulations of the transitional program and the actions of the university at large while Anthony claimed that his inactions led to a period of academic suspension from university before he regroup and was reinstated.

Regrouping

Porter (1999) uses the term relapse to depict an apparent return to prior behaviours and says that it “is simply a signal for an underlying need to return and complete the work of an earlier stage” (p. 87). This is problematic for two reasons. Firstly, the language of relapse suggests failure and needs to be reframed since, for these respondents at least, this phase is part of their ongoing transformative processes. Additionally, the developmental perspective implied by the notion of “unfinished business,” while it may account for some retrograde occurrences, does not capture the complexity of the respondents’ experiences, which are in keeping with notions of resistance, both internal and external. The term regrouping is more positive and in keeping with the cyclical nature of change identified by Porter (1999) and Brammer (1991). Individuals in this phase are not identical to who they were at an earlier time and their internal processes may be quite different than they were previously. Envisioning transformation in this way facilitates the reframing of those experiences that Porter (1999) constructs as a Relapse Stage, and Frankel (1998) calls regression and Bridges (2001), identifies as an inability to let go. What these theorists understood as backward motion involved in change and transformation could be conceptualized as analogous to retrograde motion in a Copernican sense whereby what appears from a certain perspective to be movement backward is actually forward motion. The Regrouping Phase was not, for these participants, equivalent to re-entrenchment, regression, or reversion. Instead, it was a necessary phase during which respondents attempted to reduce internal and external dissonance, reassess and reframe their identities, and come to terms with new, and as of yet, uncomfortable and unfamiliar ways of being.

Jick (1993b) claims that because of an individual’s sense of loss related to the giving up of identities and the need to construct and make meaning of new ones, “resistance is a part of the natural process of adapting to change; it is a normal response to those who have a strong vested interest in maintaining their perception of the current state and guarding themselves against loss” (p. 330). Despite the dissonance between their lived experiences and their aspirations, there was security in knowing who they were and where they fit. Frank identified his need to regroup as recurring throughout this academic experience. At the beginning of this journey this was because he said, “I didn’t have a lot of confidence. I questioned my mental abilities.” As he achieved success, these thoughts and feelings dissipated. He expresses concern that now, “I’m at the end of it I have a lot of worries or anxiety about what I’m doing next and the fact that I’ll be not a student anymore but just an unemployed 35 year old with no particular marketable skills” (interview, January, 2004).

Carol spoke of the importance of retaining earlier friendships as a means of retaining the core of her identity while undergoing transformations in a manner consistent with Kamler’s (1994) contention that individuals “can only change identifications slowly. Demands for wholesale immediate change are not only offensive but also confused” (p. 260). In spite of the pull she felt toward the university and new relationships, she identified a need to speak in language that would be not seen as “too big” and of the importance to not give the impression she thought she was “better than or had moved ahead of” her friends. She explained how these connections grounded her.

I cried a lot. It was really difficult. Coming back to school was so hard, there were some days I just wanted to give up and go back to getting my old job back. And just being amongst those people again, it seemed so much easier. (Carol, interview, October 2003)

Other participants also spoke of their need to reconnect with family and friends from their earlier “non-academic” days in order to make sense of who they were and who they were becoming.

Frankel (1998) speaks of resistance to change and transformation as an adolescent phenomenon. “One of the inevitable struggles in adolescence is between a regressive pull back to what is known, familiar and safe, and a forward movement out into the world” (p. 6). However, a search for that which is safe is perhaps common to ventures into unfamiliar territories, regardless of age. Jennifer spoke of wanting to quit out of fear of losing friendships and she said that although her husband was incredibly supportive that a couple of times as she was growing and changing they also “had issues.”

Individuals in this phase were not identical to who they had been at an earlier time. Anthony, who became once more enmeshed in “friend and family drama” that affected his academic success in university, was able to articulate clearly these distinctions. Although, at the time of the initial interview he was on academic suspension from university, Anthony described how this was different from when he was in high school.

Back when I was a kid in high school I just didn’t want to be part of the system. I didn’t want to learn anything. I didn’t feel there was anything they could teach me that was relevant. Even though I’m on academic suspension currently, I did learn a lot of things last year. I did attend my lectures. I did do some readings. I handed in a few papers so I don’t think it was a total loss in terms of self-knowledge that I gained. Also there is the Internet, the library, books and discussions with peers of mine who are in school so it’s very much more of an academic environment right now whereas in high school it was more of a rebellion. (interview, January, 2004)

Anthony was reinstated in his program after his suspension, and subsequently graduated from the university.

The Regrouping Phase could be understood in terms of concerns about a loss of identity. Jick (1993b) claims that because of an individual’s sense of loss related to the giving up of identities and the need to construct and make meaning of new ones, “resistance is a part of the natural process of adapting to change; it is a normal response to those who have a strong vested interest in maintaining their perception of the current state and guarding themselves against loss” (p. 330). Despite the dissonance between their lived experiences and their aspirations, there was security in knowing who they were and where they fit in order to continue their transformations.

Conclusions and Implications

The participants in this study are active citizens who participate in, question assumptions and actions of, and enrich democratic communities. As they have moved through cycles influenced by internal factors and external processes that mediated varying degrees of coherence and dissonance, the respondents experienced personal and social changes, transitions, and transformations. In response to research questions asking about their academic changes and personal and social transformations, it was apparent that these intrapersonal and interpersonal interactions occurred, and were made meaningful by, relationships with others in families, schools, and communities. Although this research did not claim to establish a causal connection between shifts in academic achievement and feelings of empowerment, the data demonstrated the respondents’ increased awareness of their power to effect positive change, concurrent with improvements in academic achievement. At the same time, hegemonic structures continued to impede them and reinforce existing inequities. Seven of the interviewees have a desire to become teachers, to work with and improve the school experiences of students who are disadvantaged by educational organizations. However, the transitional programs slot their graduates into 3- year degree programs while the universities they attend only accept students who have completed 4-year degrees into their teacher education certification programs. As a result, these participants again experienced Dissatisfaction and attempted to come to terms with the dissonance between institutional discourse and action and between their aspirations and organizational barriers.

Knowledge gained from respondents’ reflections in this study enriches our understanding of the role that educators can play in creating equitable, democratic schools. This is an admittedly small study; however, the experiences of these students are not unique, as hundreds of students enrolled in transitional program annually can attest. The participants’ achievements and the descriptions of their personal and social changes, transitions, and transformations challenge educators to re-evaluate deficit approaches aimed at students’ perceived inadequacies and implement strategies that utilize and develop students’ strengths as a means of achieving equity of outcomes. Their narratives speak to the importance of congruency between their aspirations and the expectations of significant others, including, and perhaps especially, educators’ beliefs in their capabilities. The data from this sample provide an alternative vision of students who are experiencing risk in schools. There is a need for further research in this under-examined realm of education in general and specifically studies to support or refute the applicability of this metaphor to broader contexts.

The need for a sense of cohesion between the students and their educational environments that the data identifies can be created within supportive school communities demarcated by respect in the forms of inclusionary practices that envision possibilities as opposed to foci on deficits. Within this type of environment, high expectations are combined with academic and social support mechanisms. The participants comments about the presence and absence of authentic curriculum points to a need for teachers (after asking themselves what constitutes meaningful curriculum and what comprises valued knowledge) to enact inclusive, meaningful curriculum. Increased familiarity with diversity, particularly for teachers and administrators from dominant groups, will lead to reduced stereotypes that teachers hold for members of some low income and minority groups. The findings have implications for conceptions of leadership that are conducive to creating climates within which risk is reduced, resilience is fostered, and personal transformations are facilitated. The significance of relationships, connectedness, and feelings of community in the data speak to the importance for administrators to work in conjunction with students, parents, and teachers to examine definitions of success and the means used to measure and achieve equitable outcomes for all students.

References

Adger, W. N. (2006). Vulnerability. Global Environmental Change, 16(3), 268–81. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.02.006

Agnew, V. (1996). Resisting discrimination: Women from Asia, Africa, and the Caribbean and the women’s movement in Canada. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto.

Anderson, D., & Hayes, C. (1996). Gender, identity, and self-esteem: A new look at adult development. New York, NY: Springer.

Bandura, A. (2000). Exercise of human agency through collective efficacy. Current Directions in Psychological Science 9(3), 75-78.

Barr, R., & Parrett, W. (2001). Hope fulfilled for at-risk and violent youth: K – 12 programs that work (2nd ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Bethea, J., & Robinson, U. (2007). Project Reconnect: Fostering resilience within disconnected youths. Journal of Urban Learning, Teaching, and Research, 3, 5-22.

Benard, Β. (1995). Fostering resilience in children. ERIC Digest. ERICΕΟ386327. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED386327.pdf

Brammer, L. (1991). Change as challenge and opportunity. In L. Brammer (Ed.), How to cope with life transitions: The challenge of personal change (pp. 1 – 20). New York, NY: Hemisphere.

Bridges, W. (2001). The way of transitions: Embracing life’s most difficult moments. Cambridge, MA: Perseus.

Burney, V., & Beilke, J. (2008). The constraints of poverty on high achievement. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 31(3), 295-321.

Celik, D., Cetin, F., & Tutkum, E. (2015). The role of proximal and distal resilience factors and locus of control in understanding hope, self-esteem and academic achievement among Turkish pre-adolescents. Current Psychology, 34(2), 321–345. doi: 10.1007/s12144-014-9260-3

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Downey, J. (2008). Recommendations for fostering educational resilience in the classroom. Preventing School Failure, 53(1), 56-64.

Eggen, P., & Kauchak, D. (2001). Development of cognition and language. In P. Eggen & D. Kauchak (Eds.), Educational psychology: Windows on classrooms (pp. 52 – 75). Columbus, OH: Prentice Hall.

Elias, M., Parker, S., & Rosenblatt, J. (2006). Building educational opportunity. In S. Goldstein & R. Brooks (Eds.), Handbook of resilience in children (pp. 315-336). New York, NY: Springer.

Frankel, R. (1998). The adolescent psyche: Jungian and Winnicottian perspectives. New York, NY: Routledge.

Garcia, S., & Guerra, P. (2004). Deconstructing deficit thinking: Working with educators to create more equitable learning environments. Education and Urban Society, 36(2), 150-168.

Garrett, M., Parrish, M., Williams, C., Grayshield, L., Portman, T., Rivera, Ed., & Maynard, E. (2014). Invited commentary: Fostering resilience among Native American youth through therapeutic intervention, Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43, 470–490. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-0020-8

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gitlin, A., & Russell, R. (1994). Alternative methodologies and the research context. In A. Gitlin (Ed.), Power and method: Political activism and educational research (pp. 181-202). New York, NY: Routledge.

Goldstein, S., & Brooks, R. (2006). Why study resilience? In S. Goldstein & R. Brooks (Eds.), Handbook of resilience in children (pp. 3-15). New York, NY: Springer.

Grotevant, H., Bosma, H., de Levita, D., & Graafsma, T. (1994). Introduction. In H. Bosma, T. Graafsma, H. Grotevant, & D. de Levita (Eds.), Identity and development: An interdisciplinary approach (pp. 1 – 20). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hemmings, A. (1998). The self-transformation of African-American achievers. Youth & Society, 29(3), 330 – 368.

Jick, T. (1993a). The challenge of change. In T. Jick (Ed.), Managing change: Cases and concepts (pp. 1 – 8). Boston, MA: Irwin.

Jick, T. (1993b). The recipients of change. In T. Jick (Ed.), Managing change: Cases and concepts (pp. 322 – 333). Boston, MA: Irwin.

Johnson, G. Μ. (1997). Resilient at-risk students in the inner city. McGill Journal of Education, 32(l), 35-49.

Kaplan, H. (2006). Understanding the concept of resilience. In S. Goldstein & R. Brooks (Eds.), Handbook of resilience in children (pp. 39-47). New York, NY: Springer.

Kamler, H. (1994). Identification and character: A book on psychological development. New York, NY: State University of New York.

Kegan, R. (2000). What “form” transforms? In J. Mezirow & Associates (Eds.), Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in progress (pp. 35 – 69). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Kelly, U. (1997). Schooling desire: Literacy, cultural politics, and pedagogy. New York, NY: Routledge.

Kroger, J. (2000). Identity development: Adolescence through adulthood. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Lester, J. (2004). Spirit, identity, and self in mountaineering. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 44(1), 86-100.

Luthans, F., Vogelgesang, G., & Lester, P. (2006). Developing the psychological capacity of resilience. Human Resources Development Review, 5(1), 25-44.

Marcia, J. (1994). The empirical study of ego identity. In H. Bosma, T. Graafsma, H. Grotevant, & D. de Levita (Eds.), Identity and development: An interdisciplinary approach (pp. 67 – 80). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

McMahon, B. (2004). Small steps and quiet circles: Student transformations through the enactment of resilience processes (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of TorontoToronto, ON.

McMahon, B. (2007). Resilience factors and processes: No longer at Risk. The Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 53(2), 127 – 142.

McMahon, B. (2015). Seeing strengths in a rural school: Educators’ conceptions of individual and environments resilience factors. Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies 13(1), 238 – 267. ISSN 1740-2743

McMillan, J. Η., & Reed, O. F. (1994). At-risk students and resiliency: Factors contributing to academic success. Clearing House, 67(3), 137-40.

Merriam, S. (1998), Qualitative research and case study applications in education. , San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

Mezirow, J. (1995). Transformation theory of adult learning. In M. R. Welton (Ed.), In defense of the lifeworld (pp. 39-70). New York, NY: SUNY.

Nelson, D. R., Adger, W. N., & Brown, K. (2007). Adaptation to environmental change: Contributions of a resilience framework. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 32, 395-419.

Norman, E. (2000). The strengths perspective and resiliency enhancement—A natural partnership. In E. Norman (Ed.), Resiliency enhancement: Putting the strengths perspective into social work practice (pp. 1 – 16). New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Norum, K. (2004, April). What stories tell: Storying and restorying public education. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New Orleans. Retrieve from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED451594.pdf

Peart, N., & Campbell, F. (1999). At-risk students’ perceptions of teacher effectiveness. Journal for a Just and Caring Education, 5(3), 269 – 284.

Pianta, R., & Walsh. D. (1998). Applying the construct of resilience in schools: Cautions from a developmental systems perspective. School Psychology Review, 27(3), 407- 417.

Porter, T. (1999). Beyond metaphor: Applying a new paradigm of change to experiential debriefing. The Journal of Experiential Education, 22(2), 85 – 90.

Prochaska, J. O., DiClemente, C., & Norcross, J. (1992). In search of how people change. American Psychologist, 47(9), 1102 – 1114.

Rennie, C., & Dolan, M. (2010). The significance of protective factors in the assessment of risk. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 20, 8–22. doi: 10.1002/cbm.750

Rosenthal, R., & Jacobson, L. (1968). Pygmalian in the classroom. Urban Review 3(1), 16 - 20.

Seidman, S. (1998). Dislodging the canon: The reassertion of a moral vision of the human sciences. In S. Seidman (Ed.), Contested knowledge: Social theory in the postmodern era (2nd ed., pp. 171-343). Maiden, MA: Blackwell.

Smokowski, P., Reynolds, A., & Bezruczko, N. (1999). Resilience and protective factors in adolescence: An autobiographical perspectives from disadvantaged youth. Journal of School Psychology, 37(4), 425 – 448.

Taylor, E. W. (2008). Transformative learning theory. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 119, 5 – 15.

Taylor, E., & Thomas, C. (2001). Resiliency and its implications for schools. Journal of Thought, 36, 7 – 16.

Walker, C., Gleaves, A., & Grey, J. (2006). Can students within higher education learn to be resilient and, educationally speaking, does it matter? Educational Studies, 32(3), 251-264.

Westfall, A., & Pisapia, J. (1994). Students who defy the odds: A study of resilient at-risk students. Richmond, VA: Metropolitan Educational Research Consortium.

Widdershoven, G. (1994). Identity and development: A narrative perspective. In H. Bosma, T. Graafsma, H. Grotevant, & D. de Levita (Eds.), Identity and development: An interdisciplinary approach (pp. 103 – 117). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Williams, J., Aiyer, S., Durkee, M., & Tolan, P. (2014). The protective role of ethnic identity for urban adolescent males facing multiple stressors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 3, 1728–1741. DOI 10.1007/s10964-013-0071-x

__________________

Endnote

1Although students are able to enroll in university programs without graduating from high school, transitional and bridging or articulation programs have been established to assist students who are deemed to have the ability to be successful in university and who have not yet consistently demonstrated the requisite knowledge, skills, and confidence.