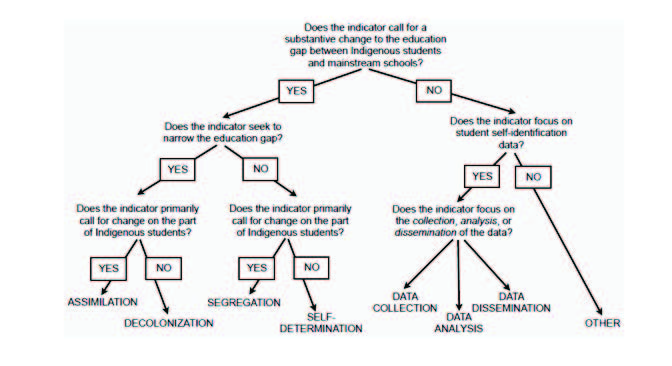

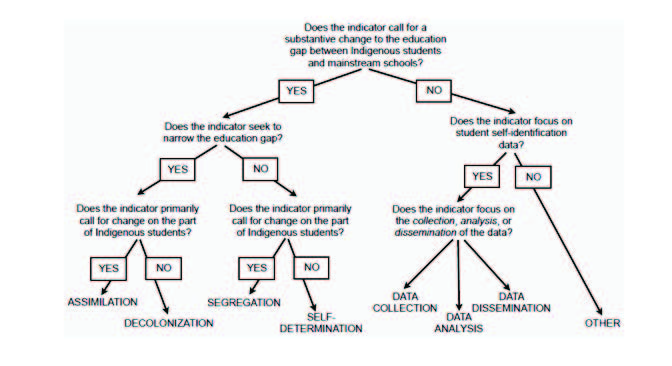

Figure 1. The decision scheme for the content analysis of ministry documents

The Gap Between Text and Context: An Analysis of Ontario’s Indigenous Education Policy

Jesse K. Butler

University of Ottawa

For an individual, one of the definitions of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again in the same way and expecting different results. For a government, such behaviour is called … policy.

—Thomas King (2012, in The Inconvenient Indian, p. 95)

The Ontario First Nation, Métis, and Inuit Education Policy Framework (hereafter referred to as the Framework), first published in 2007, is premised on the idea that an “achievement gap” exists between Indigenous students attending Ontario’s public schools and the broader student population. In this and subsequent publications from the Ontario Ministry of Education (OME), the “voluntary, confidential self-identification” (OME, 2007b, p. 7) of Ontario’s Indigenous students is proposed as a first step in resolving this problem. The logic goes that by mapping who and where Indigenous students are, the Ministry and school boards can better target programs and initiatives to improve their educational achievement. Furthermore, the Framework asserts that, by collecting consistent data on the achievement of self-identified Indigenous students, the Ministry can continually monitor, evaluate, and improve these programs, in order to better help Indigenous students.

Previous studies authored by Cherubini and colleagues have pointed to problems with this line of logic. These authors have argued that the achievement gap perceived between Indigenous and “mainstream” students simply indicates the ongoing colonial legacy of Eurocentric education—and that the real “gap,” therefore, is an epistemological one (Cherubini & Hodson, 2008; Cherubini, Hodson, Manley-Casimir, & Muir, 2010). Furthermore, they have contended that the promotion of self-identification in the Framework and its companion document, Building Bridges to Success for First Nation, Métis, and Inuit Students (hereafter referred to as Building Bridges), reinforces this colonial legacy, through ongoing practices that isolate Indigenous students in order to evaluate them according to Eurocentric criteria (Cherubini, 2010; Cherubini & Hodson, 2008).

In this paper, I build on the work of Cherubini and colleagues by looking at these issues as they are manifested in the Implementation Plan (OME, 2014) that was recently published for the Framework. As I demonstrate below, there is a significant increase in the emphasis on self-identification in this most recent document. Coming just two years before the 2016 end date of the timeline laid out in the Framework, the emphasis on self-identification can no longer be accepted as a first stage in the implementation process. What, therefore, should be seen as the Framework’s (new) role in Ontario’s Indigenous education strategy? In order to answer this question, I draw on Indigenous education scholars to map out four possible responses to a gap between Indigenous students and mainstream schooling—assimilation, segregation, decolonization, and self-determination. Then, through a content analysis of the strategies listed in the Framework and the Implementation Plan, I explore the complex relationship of self-identification to these four strategic directions. I argue that, in many ways, the current direction of Ontario’s Indigenous education policy moves toward data management in the place of substantive action. Moreover, in so far as actions are proposed, they mostly suggest a shift back toward colonial practices of assimilation and segregation.

This paper began with excitement on my part regarding the pedagogical possibilities presented by the Framework (Cherubini, 2009; Kearns, 2013). I have been volunteering as a tutor at one of the Alternate Secondary School Programs (ASSPs) in Ontario run as partnerships with local Indigenous Friendship Centres. Based on my experience, I consider these programs to be immensely valuable as a practical step toward educational self-determination for urban First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities. On initially reading the Framework document, I was excited by the way these programs seem to be highlighted in the document as a flagship program of the larger policy. I was surprised, therefore, when I subsequently found no reference to the ASSPs in the Implementation Plan. On a closer reading, I noticed an astonishing lack of reference to any specific programming. Simultaneously, I noticed a curious repetition of the term “self-identification.”

|

Document (Year) |

Total Pages |

Term |

Total References |

References per Page |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Framework (2007) |

41 |

“self-identif” |

7 |

0.17 |

|

“program” |

43 |

1.05 |

||

|

Progress Report (2009) |

24 |

“self-identif” |

17 |

0.71 |

|

“program” |

20 |

0.83 |

||

|

Progress Report (2013) |

52 |

“self-identif” |

66 |

1.27 |

|

“program” |

20 |

0.38 |

||

|

Implementation Plan (2014) |

21 |

“self-identif” |

23 |

1.1 |

|

“program” |

5 |

0.24 |

In order to determine if I was observing a genuine pattern, I compared the four official releases on the Framework—the Framework itself (OME, 2007a), the two Progress Reports (OME, 2009, 2013), and the Implementation Plan (OME, 2014). In the PDF version of each of these documents I searched for “self-identif” (in order to catch all the variants of “self-identification”), and “program,” then divided the total number of references for each document by the number of pages in that document. The result was an approximate metric, which suggested a significant increase over time in the number of references per page to self-identification, and a converse decrease in the number of references per page to programming, as can be seen in Table 1. These initial numbers were exploratory, but they suggest a troubling pattern, which the rest of this paper is intended to unpack. Based on the rhetoric of the Framework, which I discuss more in the next section, the implementation of the policy should have focused initially on collecting student self-identification data, then subsequently on implementing specific programming for these self-identified students. My initial findings suggested that the policy priorities actually moved in the opposite direction.

In order to explore the meaning of these patterns, I adopted qualitative content analysis as a methodology. As Krippendorff (2004) explains, content analysis is a methodology for determining patterns in texts, in order to draw inferences about related patterns in the contexts in which those texts are produced or used. According to Morgan (1993), a qualitative approach to content analysis is not characterized by an absence of quantification. Rather, it is marked by a shift in emphasis from simply quantifying patterns to suggesting what those patterns mean. In this sense, my research engages three cycles of document analysis—a qualitative cycle to determine the context for the study, a quantitative cycle to determine patterns in the texts and by inference in their contexts, and a final qualitative cycle to suggest the meaning of these patterns.

Since content analysis is primarily concerned with what texts can tell us about their contexts, it is best used when direct observation of those contexts is not an option (Krippendorff, 2004). In analyzing these policy documents, I am not presuming to infer from them precisely what is happening in schools or in the Ministry—both of which questions are best served by more direct and interactive methodologies. Rather, my purpose is to suggest what discursive shifts can be seen in the documents over time, and how these discursive shifts potentially constrain the range of possible actions open in the future. While it is important to recognize that teachers interpret policy documents in highly variant and situated ways, this does not mean that the text has no impact on their choices and actions. As Krippendorff (2004) explains, “Texts, messages, and symbols never speak for themselves. They inform someone. Information allows a reader to select among alternatives. It narrows the range of interpretations otherwise available” (p. 25). Ball, Maguire, Braun, and Hoskins (2011a, 2011b) have similarly pointed to the ways in which educational policy texts restrict the possible responses of policy actors.

In engaging with the content of these policy documents, I find myself obliged to engage with their terminology. In particular, in this paper I adopt the language of a gap between Indigenous and “mainstream” students. Following Cherubini et al. (2010), I think of this gap not merely as an achievement gap but as a more general gap in educational outcomes—including, for instance, students’ satisfaction with their education. Nonetheless, I acknowledge that this language can be problematic. As Gillborn (2008) argues, “gap talk” is often used to disguise systematic inequality through superficial indicators of progress: “The repeated assertion that the inequalities are being reduced fails to recognize the scale of the present inequality and how relatively insignificant the fluctuations really are” (p. 65). In particular, an emphasis on closing a gap in educational outcomes can disguise the need for broader economic redistribution in order to achieve genuine equality (Gillborn, 2008; Martino & Rezai-Rashti, 2013). The gap talk in Ontario policy, furthermore, is part of a much larger pattern, operating within a globalized neoliberal culture of accountability that negates differences by assuming quantifiable equivalence (Ball, 2012; Martino & Rezai-Rashti, 2013). In spite of these constraints, however, I believe the analysis of educational gaps can be done responsibly, by acknowledging broader patterns of inequality, and by leaving room for the disadvantaged groups to define their differences on their own terms. In their better moments, I believe the Ministry of Education is pushing their analysis in this direction, and I engage them in this gap talk in the hope that it can be a tool for recognizing and combatting inequalities, rather than for enforcing monolithic accountability.

Finally, my critique here is not intended to question the fact that good teachers in Ontario can and do utilize the Framework document to improve the educational experiences of their First Nations, Métis, and Inuit students (Cherubini, 2009; Kearns, 2013). In the words of Kearns (2013):

I want to acknowledge that within the tensions of policy intent and practice, and within the challenges of the legacy of a Eurocentric educational system that continues to enact colonial privilege, spaces have been created that value Indigenous people, which I also recognize as fluid and changing as different people move in and out of these spaces and roles. (p. 88)

Such spaces are created in Ontario schools, and the Framework has, at least occasionally, been a resource to enable the creation of such spaces. However, precisely because of the important potential of the policy, I am concerned about how this potential may be constrained by discursive shifts in the documents.

According to Cherubini and Hodson (2008), the emphasis on Indigenous student self-identification in the Framework is problematic at best. In their words:

Aboriginal peoples are being asked to voluntarily self-identify themselves so that a mainstream branch of the government (EQAO) can publish and disseminate the results of Aboriginal students’ achievement on standardized assessments that are exclusively emblematic of colonial measures of academic success. (p. 17)

Cherubini (2010) goes on to suggest that it is problematic to treat a student’s self-identification as a permanent statement of their identity. According to Restoule (2000), identifying, which is specific and contextual, should be understood differently from a permanent, fixed identity. It appears, however, that the Ministry is taking students’ contextual identifications and turning them into permanent and reified identities by fixing them in student records. In a report on inter-jurisdictional practices in self-identification, the Educational Policy Institute (2008) asked all Canadian Ministries of Education how they accounted for potential instability in students’ identities. At the time, only Saskatchewan had established a framework in which students could change their identification year to year. Other ministries had not apparently given the issue serious consideration, but simply filed the information in student records. In the Framework, the Ministry appears to respond to the problematic nature of self-identification by framing its data-collection as a limited and contextual undertaking, for the purpose of implementing specific programs. As I discuss below, however, the emerging evidence from school boards suggests a very limited effort on the part of the Ministry to implement these targeted programs, raising the question of what purpose the collection of self-identification data is serving.

The original Framework document makes reference to the importance of having “reliable and valid data” (OME, 2007a, p. 10) in order to achieve the Framework goals, and indicates the Ministry’s intention to provide a resource guide on Indigenous student self-identification to help school boards gather this data. Building Bridges, published later that year, seems to make clear the Ministry’s purpose in encouraging self-identification. This purpose is explained in a stand-alone sentence on the first page: “The availability of data on Aboriginal student achievement in Ontario’s provincially funded school system is a critical foundation for the development, implementation, and evaluation of programs [emphasis added] to support the needs of First Nation, Métis, and Inuit students” (OME, 2007b, p. 3). The focus on programming here clearly aligns with the strategies laid out in the Framework. However, it also has a pragmatic purpose within this document. Building Bridges goes on to explain a three-step process for school boards to follow in creating self-identification policies, in which the first step is building awareness of the significant legal ramifications of collecting sensitive personal student information. Boards are instructed to be cautious about making sure they have a clear purpose for collecting these data. This purpose should directly benefit the students involved and be easily communicable to the public. The document goes on to state that it is “essential” for school boards to communicate to parents that self-identification is for the purpose of creating specific, targeted programming (pp. 12-13).

Despite these stated intentions, the Auditor General of Ontario (AGO) found five years later that very little had been accomplished either in terms of data collection or programming (AGO, 2012). In contrast to other Ministry initiatives, the Auditor General noted a lack of both a clear action plan and a means to measure progress. In particular, little progress had been made in regard to Indigenous student self-identification, mostly, in the Auditor General’s view, because of a lack of centralized leadership from the Ministry. The Auditor General states:

Five years after the release of the Framework, the Ministry has still not developed a formal implementation plan. In our opinion, such a plan should identify the key obstacles faced by Aboriginal students and outline specific activities to overcome various obstacles. (AGO, 2012, p. 133)

The Auditor General specifically calls for a combination of strategic action and targeted data collection, in line with the Ministry’s original statements in 2007.

Despite the Auditor General’s critique, the Progress Report (OME, 2013) published the next year claims important steps forward in achieving the Framework goals, including Indigenous student self-identification. Initial baseline achievement data for 28,079 self-identified Indigenous students are presented, based on EQAO scores and Grade 9 credit completion. Looking forward, this document states: “The next phase of implementation will sustain the critical activities [emphasis added] established in the first six years to support system-wide integration of Aboriginal perspectives into the provincial education system” (OME, 2013, p. 47). The 2013 Progress Report states the Ministry’s commitment to release an implementation plan for the following year, and ends with a list of seven priorities. Two of these priorities relate to the collection and use of student self-identification data, while the rest suggest more substantive changes to how Indigenous education is actually carried out in schools, such as a commitment to increase “awareness of Aboriginal perspectives, histories, languages and cultures” (OME, 2013, p. 48).

A recent article by Anuik and Bellehumeur-Kearns (2014) again raises questions about actual progress made in implementing the Framework. They conclude:

From our surveys, personal interviews and site visits, we see that some boards are showing that steps can be taken toward recognizing Aboriginal people and implementation of the Framework; however, it would appear from the lack of engagement and responses that many boards (well over half) need to begin to work on the initiatives set forth in the Framework. (pp. 29-30)

Implementation of self-identification in their findings was not just uneven from board to board, but even within individual boards. Many of their interviewees’ comments reinforce Cherubini and Hodson’s (2008) concerns that efforts to categorize Indigenous students in this way would simply be seen by Indigenous communities as a return to past colonial education policies. As a result, many Indigenous students and parents choose not to participate in the programs. Anuik and Bellehumeur-Kearns (2014) found that self-identification data in any particular board was so uneven and unreliable that boards needed to supplement these data with data from other sources, including the 2006 census. As a result, they question whether self-identification data in isolation would ever provide meaningful results.

Anuik and Bellehumeur-Kearns (2014) also argue, however, that the primary benefit of the Framework has not been the data it has generated but the opportunity it has provided to make Indigenous cultures more prominent in schools and classrooms. A positive emphasis on Indigenous cultures can improve Indigenous students’ sense of pride in their cultures, and thereby gradually increase their willingness to self-identify as a positive personal choice. However, this process again suggests the need for self-identification to be understood contextually, according to the situated needs of particular students, rather than as a formal and permanent bureaucratic structure, and for the collection of such data to result directly in targeted and beneficial programming. If, however, as this section has suggested, this programming has not been forthcoming, then what purpose can the self-identification data be understood to serve?

Conceptual Framework: Four Responses to the Education Gap

While there is general disagreement on what the gap between Indigenous students and mainstream schooling means or how to resolve it, most stakeholders in Indigenous education agree that a gap of some sort exists (Cherubini et al., 2010). If, as the Ministry states (OME, 2007a), the purpose of its Indigenous education policy is to close this gap, then any evaluation of the policy should begin with an analysis of what exactly this gap is, and what it would mean to close it. In this section, therefore, I draw upon Indigenous education scholars to theorize the nature of the education gap, and possible responses to it. This analysis is theoretical and schematic, and the possibilities I indicate are abstractions that will inevitably be complicated in any concrete application. In particular, I want to acknowledge that individual students will relate to the theoretical gap between Indigenous students and mainstream schools in complex and variable ways. As Little Bear (2000) makes clear, Indigenous students must live their lives across multiple cultures and worldviews. Many Indigenous students are highly successful in public schools, and I am not suggesting that they should be viewed as assimilated. My point here is to map out the theoretical implications of the gap that the Ministry of Education has identified, and the broad ethical implications of the various policy responses that could be made in response.

Logically, in order to close any gap, one of the two sides of the gap must be moved toward the other. In the case of Indigenous education policy in Canada, the government has generally assumed that the gap between Indigenous students and public schools must be closed by changing Indigenous students to bring them closer to Western standards. This approach can be called assimilation (Weenie, 2008), and it is rooted in the colonial assumption that Western standards are timeless and universal and that other cultures must adapt to fit them (Battiste, 1998). There is no logical reason, however, why the movement to close the gap cannot happen the other way, by moving schools closer to the epistemic reality of Indigenous students, either through broad curricular reform (Battiste, 2011, 2013) or through changing teaching practices to be more culturally relevant (Redwing Saunders & Hill, 2007). Following Battiste (2013) and Aquash (2013), I refer to this approach to closing the gap as decolonization (however, for a critique of this use of decolonization, see Tuck & Yang, 2012).

While assimilation and decolonization can be understood as the only two logical options to close the education gap, Indigenous education scholars have indicated two other potential responses that allow the gap to remain in place. On the one hand, segregation was traditionally used to isolate Indigenous students, and move mainstream schooling farther away from responding to their needs (Weenie, 2008). This can be seen in Donald’s (2009) analysis of Indigenous education in Canada through the insider/outsider relations of the frontier fort. More specifically, Donovan (2011) suggests that practices of categorizing urban Indigenous youth as “at risk” can be a form of segregation. On the other hand, some scholars advocate self-determination as a way for Indigenous communities to move away from Western educational models by establishing localized control over schooling (Aquash, 2013; Restoule, Gruner, & Metatawabin, 2013). The control involved is not necessarily binary—particularly in urban contexts self-determination must be negotiated in complex ways (Peters, 2005). However, an important aspect is the shift away from a generalized “pan-indigenous” approach to culturally relevant curriculum, and toward curriculum developed in relation to the needs of the local community (Donald, Glanfield, & Sterenberg, 2011).

In what follows, I use these four potential responses to the education gap as a conceptual framework to understand what it would mean to make substantive change to the educational status quo for Indigenous students. Following from my analysis of the Ministry’s rhetoric in the previous section, one would expect the early years of Ontario’s Indigenous education policy to emphasize data collection, then the later years to emphasize substantive programs to change the educational status quo through some combination of these four options. In line with my initial findings, however, I find a significant shift in the Implementation Plan away from substantive programming and toward data management. Furthermore, insofar as substantive programming is advocated, the Implementation Plan also indicates a shift back toward the colonial responses of assimilation and segregation.

The second, quantitative aspect of my study consists of a content analysis of the Framework and the Implementation Plan. Each of these two Ministry documents consists largely of a list of specific indicators regarding what the policy is expected to achieve. These lists of indicators lend themselves to content analysis as they provide discrete units that can be coded and counted (Bauer, 2000). The other parts of each document—front matter and appendices—were utilized for my contextualizing qualitative analyses, but were set aside for this quantitative analysis, on the logic that the indicators are the clearest statement of the Ministry’s intended actions. This content analysis was conducted using a decision scheme, in which “each recorded datum is regarded as the outcome of a predefined sequence of decisions” (Krippendorff, 2004, p. 135). This decision scheme was developed partially deductively, through my review of the literature, but then refined inductively through my first cycle coding of the Framework (MacQueen, McLellan, Kay, & Milstein, 1998/2009). In the decision scheme, I asked first whether each indicator sought to substantively change the education gap, as defined in the previous section, and then which of the four possible responses best describes it—assimilation, segregation, decolonization, or self-determination. For indicators that do not seek to change the education gap, I, then, asked whether they are focused on student self-identification data, and then whether they focused on the collection, analysis, or dissemination of the data. A final category, other, was reserved for indicators focused neither on substantively changing the education gap nor on data (Bauer, 2000). The decision scheme is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure

1. The decision scheme for the content analysis of ministry

documents

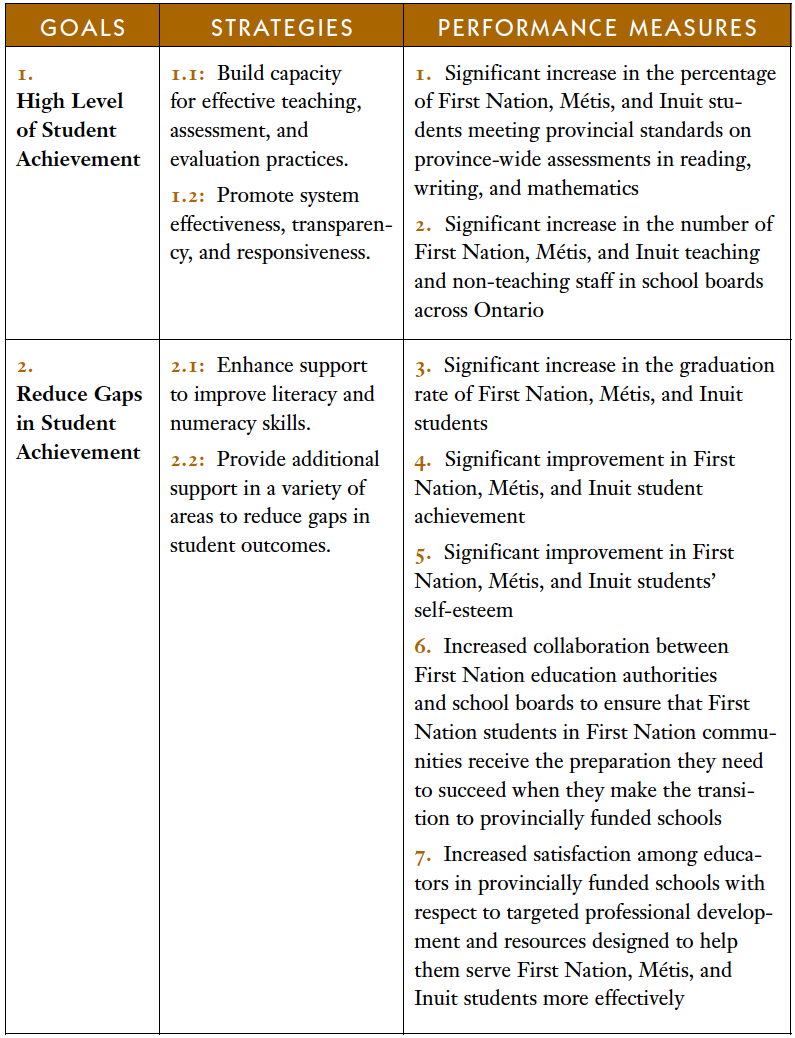

There are 81 indicators in the Framework, and 57 in the Implementation Plan. In both documents, these indicators are organized in relation to a series of larger categories, identified in the documents as “goals,” “strategies,” and “measures.” The same 10 “measures” are maintained in both documents, but the Implementation Plan replaces the earlier “goals” and “strategies” with a new set of strategies. In Figures 2-7, below, I have copied the goals, strategies, and measures as they appear in the two documents.

Figure

2. Goals, strategies, and measures in the Framework (OME,

2007a, p. 21)

Figure 3. Goals, strategies, and measures in the Framework (OME, 2007a, p. 22)

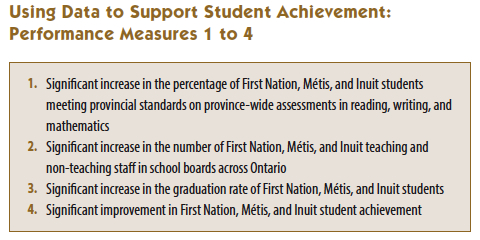

As can be seen in Figures 2 and 3, the initial measures are organized in the Framework in relation to “goals” calling for clear and measurable changes in the educational status quo—for example, “high level of student achievement” and “reduce gaps in student achievement”—and similarly clear “strategies.” In Figures 4, 5, 6, and 7, however, it can be seen that these same measures are reframed in the Implementation Plan in relation to more nebulously worded goals—for example, “using data to support student achievement” and “supporting students”—indicating again a shift away from substantive action and toward mere data management.

Figure

4. Strategies and measures in the Implementation Plan:

Using Data to Support Student Achievement (OME, 2014, p. 9)

Figure

5. Strategies and measures in the Implementation Plan:

Supporting Students (OME, 2014, p. 11)

Figure

6. Strategies and measures in the Implementation Plan:

Supporting Educators (OME, 2014, p. 13)

Figure 7. Strategies and measures in the Implementation Plan: Engagement and Awareness Building (OME, 2014, p. 15)

While my analysis focuses on the indicators, I also separately coded these ten measures in order to better contextualize the indicators. All of the measures are quite specific and quantifiable, and mostly call for “significant increases” in Indigenous students’ academic achievement or in Indigenous communities’ involvement in the education system. In terms of their strategic direction, I consider them quite balanced, having coded five as decolonization, four as assimilation, and one as other. These measures and their codes can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2

The Ten “Measures” Common to Both Documents

|

Measures (OME, 2007a, pp. 21-22) |

Codes |

|---|---|

|

1. Significant increase in the percentage of First Nation, Métis, and Inuit students meeting provincial standards on province-wide assessments in reading, writing, and mathematics |

ASSIMILATION |

|

2. Significant increase in the number of First Nation, Métis, and Inuit teaching and non-teaching staff in school boards across Ontario |

DECOLONIZATION |

|

3. Significant increase in the graduation rate of First Nation, Métis, and Inuit students |

ASSIMILATION |

|

4. Significant improvement in First Nation, Métis, and Inuit student achievement |

ASSIMILATION |

|

5. Significant improvement in First Nation, Métis, and Inuit students’ self-esteem |

DECOLONIZATION |

|

6. Increased collaboration between First Nation education authorities and school boards to ensure that First Nation students in First Nation communities receive the preparation they need to succeed when they make the transition to provincially funded schools |

ASSIMILATION |

|

7. Increased satisfaction among educators in provincially funded schools with respect to targeted professional development and resources designed to help them serve First Nation, Métis, and Inuit students more effectively |

DECOLONIZATION |

|

8. Increased participation of First Nation, Métis, and Inuit parents in the education of their children |

DECOLONIZATION |

|

9. Increased opportunities for knowledge sharing, collaboration, and issue resolution among Aboriginal communities, First Nation governments and education authorities, schools, school boards, and the Ministry of Education |

OTHER |

|

10. Integration of educational opportunities to significantly improve the knowledge of all students and educators in Ontario about the rich cultures and histories of First Nation, Métis, and Inuit peoples |

DECOLONIZATION |

My coding of the indicators in the two documents again suggests a significant shift away from action and toward data management. The totals for each document can be seen in Table 3. In what follows, I discuss these coding results, providing examples of how I coded the indicators and providing some initial analysis of what these numbers might mean.

Table 3

Quantitative Results of my Coding for the Indicators in each Document

|

Codes |

Framework |

Implementation Plan |

|---|---|---|

|

Document Total |

81 (100%) |

57 (100%) |

|

ASSIMILATION |

23 |

8 |

|

DECOLONIZATION |

34 |

14 |

|

SEGREGATION |

6 |

3 |

|

SELF-DETERMINATION |

5 |

0 |

|

ProgramsTotal |

68 (84%) |

25 (43.9%) |

|

DATA COLLECTION |

2 |

5 |

|

DATA ANALYSIS |

0 |

8 |

|

DATA DISSEMINATION |

0 |

7 |

|

Data Total |

2 (2.5%) |

20 (35%) |

|

OTHER |

11 |

12 |

In the Framework, only 11 of the 81 indicators did not focus on substantive change to the status quo. Only two of these focused on self-identification data, both of which I coded as data collection. For instance, school boards are instructed to: “consult on, develop, and implement strategies for voluntary, confidential Aboriginal student self-identification, in partnership with local First Nation, Métis, and Inuit parents and communities” (OME, 2007a, p. 12). There were nine indicators I coded as other because they emphasized neither direct changes to the education gap nor self-identification data. Eight of these concerned some form of cooperation with Indigenous communities and organizations—such as the ASSP partnerships with Friendship Centres—but without any detail as to how exactly this would affect the education gap.

The remaining 68 indicators in the Framework all call for some form of substantive action (34 decolonization, 23 assimilation, 6 segregation, and 5 self-determination). The preponderance of decolonization and assimilation suggests that the Ministry’s primary purpose is to bring Indigenous students and mainstream education closer together, through movement on both sides. The decolonization indicators primarily refer to increases in culturally relevant teaching practices. Most of these Indicators are clustered under Strategies 1.1 and 3.2, which call for more effective teaching and the incorporation of more Indigenous knowledge, respectively. Indicators coded as assimilation are spread more evenly through the document, suggesting a more general emphasis. Taken together, these two emphases could suggest that the Ministry expects that a specific focus on more culturally relevant teaching will enable Indigenous students to assimilate into Western notions of academic success.

Though they are much less frequent, both segregation and self-determination are present, particularly in Strategy 2.2, which calls for “additional support” (OME, 2007a, p. 15). For instance, school boards are called upon both to “provide First Nation, Métis, and Inuit students with access to programs that focus on Aboriginal cultures and traditions and are delivered by Aboriginal staff” and to “develop lighthouse programs focused on Aboriginal students under the ministry’s Student Success and literacy/numeracy initiatives” (OME, 2007a, p. 16). I coded the former as self-determination and the latter as segregation, due to the question of who is theoretically directing the program priorities in each case—“Aboriginal staff” in the former and ministry initiatives in the latter.

In contrast, my coding of the Implementation Plan indicates a significant shift away from substantive action and toward data management. Of the 57 total indicators, 25 were coded as one of the four categories of strategic action (i.e. decolonization, assimilation, self-determination, segregation), and a full 20 were coded as one of the three stages of data management (i.e. collection, analysis, dissemination). In regard to substantive action, decolonization and assimilation remained the most common codes, with 14 and eight, respectively. Decolonization is even more concentrated here than in the Framework, with most of its indicators clustered under one of the four strategies, called “Supporting Educators” (OME, 2014, p. 13; see Figure 6, above). “Supporting Educators,” in fact, draws on only one of the measures from the original Framework, and expands it to eight total indicators, all of which I coded as decolonization. In this sense, the Implementation Plan indicates a continuation of—if not an increased emphasis on—the theme of culturally relevant teaching. It should also be noted, however, that the indicators coded as decolonization in this document are not as easily categorized as in the Framework. For instance, one indicator asks school boards to “facilitate professional development opportunities for teaching staff to assist them in incorporating culturally appropriate pedagogy into practice to support Aboriginal student achievement, well-being, and success [emphasis added]” (OME, 2014, p. 13). The italicized words here are language that normally fell within assimilation codes in the Framework. I coded it as decolonization here because the substantive action it calls for involves “incorporating culturally appropriate pedagogy,” with the last phrase serving more of a rhetorical function to remind the reader of the Ministry’s larger purpose. Nonetheless, this detail is important to note, as it reinforces the earlier suggestion that the Ministry is encouraging culturally relevant pedagogy specifically in the expectation that it will aid in assimilating students into Western learning standards. The discursive shift from the 2007 to the 2014 document also suggests a gradual incorporation of neoliberal accountability discourses into the work of the Ontario Ministry of Education (Ball, 2012; Pinto, 2012).

Meanwhile, there is a sizeable increase in the number of indicators related to data management, from two of the 81 indicators in the Framework (2.5%) to 20 of the 57 indicators in the Implementation Plan (35.1%). This runs directly counter to the Ministry’s previous publications (OME, 2007a, 2007b, 2009, 2013), which stated an intention to build a data management structure in the early years of the policy in order to plan, target, and evaluate specific programs for Indigenous students in the later years. While eight of the 20 indicators in the Implementation Plan relate to data analysis and seven to data dissemination (which, in proper proportion to substantive actions, could complement the original plan), five of them relate to data collection. This is up from just two in the Framework. Furthermore, while three of these five indicators are in the plan for Year 1 (2013-2014), the last two are in the plan for Years 2 and 3, taking it right to the stated end date of the policy in 2016. For instance, the Implementation Plan states that in Years 2 and 3 the Ministry will: “identify and fund additional strategies to increase the voluntary, confidential self-identification of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit students” (OME, 2014, p. 16). This again raises the question: For what purpose is the Ministry pursuing Indigenous student self-identification? If, as they have stated, the purpose is to establish baseline data in order to implement and evaluate targeted programs, then they are apparently still creating their baseline, and will be until the end of the implementation period. When 2016 arrives, will they simply admit that they have taken a decade to establish their baseline, and finally begin to implement the targeted, measurable programs they suggested in 2007?

The quantitative analysis in the previous section identified a troubling shift from the 2007 Framework to the 2014 Implementation Plan. First, I found that there was a significant decrease in the number of indicators calling for substantive change to the status quo of the education gap between Indigenous and “mainstream” students, from 68 (84.0%) to 25 (43.9%). Secondly, I found a concomitant increase in the number of indicators calling for the collection, analysis, and dissemination of data on the self-identification of Indigenous students, from 2 (2.5%) to 20 (35.1%). Within the indicators calling for substantive change, the amount coded as decolonization, assimilation, and segregation remained roughly equivalent between the two documents. However, the number of indicators coded as self-determination dropped from five to zero. Again, this suggests a de-emphasizing of any substantive change to the status quo, other than continued calls for culturally relevant pedagogy—, which seems to be linked to an intent to assimilate Indigenous students into Western standards of “success.” Finally, within the indicators focused on self-identification data, I found that the Implementation Plan continues to call for data collection right up until the 2016 end date of the original Framework. This raises the question of whether the Ministry will use this data to continue developing and evaluating programs beyond 2016.

While I certainly do not want to discount the possibility that the Ministry will continue past 2016 to implement targeted programming, the currently available information indicates that they plan to hold to their original end date. The Implementation Plan states that in 2016 a third Progress Report will address “progress made in reducing gaps in student achievement, as measured against the 2011-12 baseline data on the achievement of self-identified Aboriginal students” (OME, 2014, p. 18). The baseline data presented in 2013 was scant, and any conclusions drawn from it are probably unreliable. However, changing the data-gathering process in the middle of a longitudinal study is not a way to increase reliability. This again raises the question of what the Ministry is trying to achieve with this late push for Indigenous student self-identification. This section will explore this question through a final qualitative analysis.

The content analysis findings indicated a shift in the Implementation Plan away from substantive action and toward data management. My reading of how the original measures from the Framework are reframed supports this finding. In the Framework, the first goal, “high levels of student achievement” (OME, 2007a, p. 21), contained two measures, calling for significant increases in the number of Indigenous students meeting provincial standards on standardized assessments and in the number of Indigenous teachers and staff in schools (see Figure 2, above). The first of these is an assimilation approach, while the second is a decolonization approach. What these two measures have in common, however, is that both call for substantive change. In the Implementation Plan, these two measures are combined with two others calling for an increase in Indigenous student achievement, and all bundled together under the strategy “using data to support student achievement” (OME, 2014, p. 9; see Figure 4, above). These Measures are then explained through a list of 16 indicators, of which eight relate to data management. Only three of these indicators call for a substantive change, and all of them take an assimilation approach to bringing Indigenous students in line with Eurocentric standards of success. It appears that the measures from the Framework have been repackaged in this way to emphasize data management and de-emphasize substantive action, particularly where it requires a large investment in transforming our educational system.

This reframing of the Framework to de-emphasize substantive action also extends to the theme of collaboration with Indigenous organizations. Eight of the 11 indicators coded as other in the Framework suggest some such form of cooperation, compared to just two of the 12 indicators coded as other in the Implementation Plan. Furthermore, the language of the Implementation Plan hints at consultation in a way that seems intentionally misleading. On the last page, it states, “The Ministry of Education and school boards, working with First Nation, Métis, and Inuit partners, share the view that conditions for future success have been established through progressive collaboration and specific supports and that significant progress can be achieved” (OME, 2014, p. 19). The actual semantic statement being made here is: The Ministry of Education and school boards share the view that conditions for future success have been established. However, by inserting the phrase “working with First Nation, Métis, and Inuit partners” adjacent to the subject (“the Ministry of Education and school boards”), the reader is given the impression that this statement of progress is the result of genuine consultation, rather than a seemingly unilateral process.

This apparent lack of collaboration can also be linked to the absence of indicators related to self-determination. Of the five such indicators in the Framework, two referred specifically to ASSPs in Native Friendship Centres. While there has not been sufficient research on these programs in Ontario, Donovan’s (2011) case study of one ASSP (along with my anecdotal experience in a different ASSP) suggests that these programs can provide a meaningful degree of educational self-determination for Indigenous communities in urban contexts. The ASSPs are also highlighted in the Framework through being placed first in the (non-alphabetical) list of exemplary programs presented in Appendix B. This suggests that in 2007 the Ministry considered them a flagship initiative. The 2009 Progress Report also mentions the ASSPs positively, stating:

Increased self-esteem was reported by students attending Alternative Secondary School Programs within Native Friendship Centres, although it was noted that the support services and community resources provided in these programs may also have contributed to their success in school and that additional funding and resources are required to support student needs. (OME, 2009, p. 11)

The 2013 Progress Report also mentions the ASSPs, but offers no comment on their effectiveness, only stating that they had more than 1000 students enrolled (OME, 2013, p. 34). Given this declining attention to the ASSPs, it is hardly surprising that the Implementation Plan not only fails to mention the ASSPs, but also fails to mention any other meaningful collaborations aimed substantively at self-determination. The language in the 2009 Progress Report suggests that the Ministry may value increased student self-esteem, but that their funding priorities relate to quantifiable increases in student achievement on Eurocentric standardized tests (Cherubini & Hodson, 2008). This suggests a general prioritizing of assimilation over self-determination.

Taken together, these findings indicate three potential answers to the question of what purpose the emphasis on self-identification is meant to serve in the Implementation Plan. The first is that the Ministry is holding to its original purpose—to establish baseline data then implement targeted programming—but that this purpose has simply been delayed (albeit through their own inaction). If this is the case, we should expect to see a new and more solid baseline of self-identified Indigenous student achievement data in 2016, augmented by “indicators for assessing the self-esteem and well-being of Aboriginal students” (OME, 2014, p. 18) to make sure that programs like the ASSPs do not fall through the cracks. Building on this newer and more solid baseline, we should expect to see a new timeline moving beyond 2016, with clear, actionable strategies to resolve the education gap.

Secondly, self-identification may be a tool to manage expectations and justify a narrowed focus in Indigenous education. This possibility is suggested by some of the shifts in indicators from the Framework to the Implementation Plan. For instance, the Framework calls for school boards to “increase access to Native Language and Native Studies programming for all students” (OME, 2007a, p. 19). The Implementation Plan changes this to: “increase opportunities for Native languages and Native studies education, based on local demographics and student and community needs” (OME, 2014, p. 12). As Anuik and Bellehumeur-Kearns (2014) argue, the original emphasis on integrating Indigenous perspectives throughout the mainstream education experience has the potential to improve Indigenous students’ pride in their cultures. By narrowing their programming to focus only on self-identified Indigenous students, the Ministry risks creating an even greater gap between these segregated Indigenous students and the “mainstream” student population. Nonetheless, we will know that this approach is the true purpose for self-identification data if this data starts to be strategically used to de-emphasize initiatives aimed at the general student population without further substantive programs being put forward in their place.

Thirdly, the collection of self-identification data may be for the purpose of data manipulation. The available evidence (AGO, 2012; Anuik and Bellehumeur-Kearns, 2014) indicates that the Ministry has made little real effort to implement the Framework over the last eight years, and perhaps they have given up on making substantive changes to the education gap. Aside from continued efforts to increase culturally relevant teaching (which, as I argued in the previous section, appear to be viewed as a mechanism to assimilate Indigenous students to standardized assessment measures) the emphasis appears to have shifted to data for its own sake, without any clear link to targeted programming. Even the presentation of the 2013 baseline data in the Implementation Plan suggests data manipulation. For instance, it states: “Grade 3 and 6 reading scores show gaps ranging from 5 to 33 percentage points” (OME, 2014, p. 4). A consultation of the data in the 2013 Progress Report indicates the questionable manner in which this statistic was developed. First of all, the 2013 document presents the Grade 3 and Grade 6 Reading results as separate statistics, but the Implementation Plan conflates them for no apparent reason. The original numbers for each test indicate the percentage of First Nation, Métis, Inuit, English-language, and French-language students “at or above the Provincial Standard” (OME, 2013, p. 18). From this range of potential comparisons, the Implementation Plan presents the largest possible gap (Grade 6 First Nation and French-language students) and the smallest possible gap (Grade 3 Métis and English-language students), from two different tests. It is not clear what this achieves, other than to muddy the waters.

t is possible, however, that muddying the waters is precisely the intention. If the Ministry has given up on taking substantive action to resolve the education gap, the self-identification data may simply be a way to generate false measures of progress. In a New Zealand Maori context, Kukutai (2004) found that the Maori who were most likely to self-identify were those who were closest to their culture, and therefore often less adapted to Western cultural institutions. My point here is not to determine whether or not this pattern holds in Canada—I am not aware of any existing research that would answer this question. But this logic could offer another explanation of the Ministry’s focus on self-identification. By this logic, it is possible that the first wave of Indigenous student self-identifications used as a baseline in 2013 were students who more strongly identified with their culture, and therefore are not well-served by colonial standardized assessments (Cherubini & Hodson, 2008). By this same logic, it is possible that this late strong push for more self-identification data is done with the expectation that the second wave of self-identifications will consist of Indigenous students who are more adapted to Western forms of education, and therefore rank more highly in standardized assessments. If this is the case, this late push for self-identification could effectively dilute the baseline data, creating an impression of a substantive increase in self-identified students’ achievement, with no actual change in either Ministry actions or students’ experiences. We will know that this is the purpose for the self-identification data if the Ministry attempts to compare their 2016 numbers to the 2013 baseline to claim success for the overall initiative. In effect, this would mean a shift in Ontario’s Indigenous education policy toward “symbolic policy”—a policy not intended to make any substantive change in public affairs but simply to create the illusion of change (Tee, 2008). The policy set out originally to close the gap between Indigenous students and mainstream schools, but in the process it has demonstrated another gap—between text and context, between policy rhetoric and meaningful change (Tee, 2008).

As previous studies have suggested, Ontario’s First Nation, Métis, and Inuit Education Policy Framework is a complex and volatile document. It can be seen as a tool for narrowing the gap between Indigenous students and “mainstream” schools (Anuik & Bellehumeur-Kearns, 2014; Cherubini, 2009) or for widening it (Cherubini & Hodson, 2008; Cherubini et al., 2010). The 2014 Implementation Plan offers a new perspective on the meaning of the Framework and the broader scope of Ontario’s Indigenous education policy. My analysis of the Implementation Plan suggests a significant shift away from substantive action to resolve the education gap and toward the apparent collection of data for its own sake. However, the larger purpose of this data collection remains uncertain. Ideally, these data could be used to establish a new baseline from which to launch a renewed effort at achieving the Framework goals, starting in 2016. Such an effort should utilize a combination of strategies aimed at decolonizing the mainstream educational experience and increasing opportunities for the educational self-determination of Indigenous communities (Aquash, 2013; Battiste, 2011; Redwing Saunders & Hill, 2007). It should also gather and maintain the collected self-identification data in a way that allows for variability in how students self-identify over time and between contexts (Restoule, 2000). It is also possible, however, that the data will be separated from its stated purpose of evaluating specific and targeted programs, and used instead in one of two ways to reinforce the status quo. It could be used to justify a narrower focus for Ministry funding, through targeted implementation of Indigenous programming only for self-identified Indigenous students. While there is certainly a place for such targeted programming, if it becomes the primary strategy it risks segregating self-identified Indigenous students from their peers. This result would undermine the decolonizing potential of the original Framework, with its proposals to incorporate Indigenous perspectives throughout the “mainstream” schooling experience. Finally, the data could be used for the purpose of data manipulation, by comparing the student achievement data from the very different 2013 and 2016 data sets in order to generate the illusion of progress without any real, substantive change. We will see what substantive action the Ministry takes in 2016.

References

Anuik, J., & Bellehumeur-Kearns, L.-L. (2014). Métis student self-identification in Ontario’s K-12 schools: Education policy and parents, families, and communities. Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy, 153, 1-34.

Aquash, M. (2013). First Nations in Canada: Decolonization and self-determination. in education, 19(2), 120-137.

Auditor General of Ontario (AGO). (2012). 2012 annual report. Retrieved from: http://www.auditor.on.ca/en/reports_en/en12/2012ar_en.pdf

Ball, S. (2012). Global education inc.: New policy networks and the neo-liberal imaginary. New York, NY: Routledge.

Ball, S. J., Maguire, M., Braun, A., & Hoskins, K. (2011a). Policy subjects and policy actors in schools: Some necessary but insufficient analyses. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 32(4), 611-624.

Ball, S. J., Maguire, M., Braun, A., & Hoskins, K. (2011b). Policy actors: Doing policy work in schools. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 32(4), 625-639.

Battiste, M. (1998). Enabling the autumn seed: Toward a decolonized approach to Aboriginal knowledge, language, and education. Canadian Journal of Native Education, 22(1), 16-27.

Battiste, M. (2011). Curriculum reform through constitutional reconciliation of Indigenous knowledge. In D. Stanley & K. Young (Eds.), Contemporary studies in Canadian curriculum: Principles, portraits, & practices (pp. 287-312). Calgary, AB: Detselig Enterprises Ltd.

Battiste, M. (2013). Decolonizing education: Nourishing the learning spirit. Saskatoon, SK: Purich Publishing Ltd.

Bauer, M. W. (2000). Classical content analysis: A review. In M. W. Bauer & G. Gaskell, (Eds.), Qualitative researching with text, image and sound (pp. 132-152). London, UK: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Cherubini, L. (2009). “Taking Haig-Brown seriously”: Implications of Indigenous thought on Ontario educators. Journal of the Canadian Association for Curriculum Studies, 7(1), 6-23.

Cherubini, L. (2010). An analysis of Ontario Aboriginal education policy: Critical and interpretive perspectives. McGill Journal of Education, 45(1), 9-26.

Cherubini, L., & Hodson, J. (2008). Ontario Ministry of Education policy and Aboriginal learners’ epistemologies: A fundamental disconnect. Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy, 79, 1-33.

Cherubini, L., Hodson, J., Manley-Casimir, M., & Muir, C. (2010). ‘Closing the gap’ at the peril of widening the void: Implications of the Ontario Ministry of Education’s policy for Aboriginal education. Canadian Journal of Education, 33(2), 329-355.

Donald, D. T. (2009). Forts, curriculum, and Indigenous Métissage: Imagining decolonization of Aboriginal-Canadian relations in educational contexts. First Nations Perspectives, 2(1), 1-24.

Donald, D., Glanfield, F., & Sterenberg, G. (2011). Culturally relational education in and with an Indigenous community. in education, 17(3), 72-83.

Donovan, S. (2011). Challenges to and successes in urban Aboriginal education in Canada: A case study of Wiingashk Secondary School. In H. A. Howard & C. Proulx (Eds.), Aboriginal peoples in Canadian cities: Transformations and continuities (pp. 123-142). Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

Educational Policy Institute (2008). Review of current approaches to Canadian Aboriginal self-identification: Final report. Retrieved from: http://www.cmec.ca/Publications/Lists/Publications/Attachments/123/epi-report.en.pdf

Gillborn, D. (2008). Racism and education: Coincidence or conspiracy? London, UK: Routledge.

Kearns, L.-L. (2013). The Ontario First Nation, Métis, and Inuit Education Policy Framework: A case study on its impact. in education, 19(2), 86-106.

King, T. (2012). The inconvenient Indian: A curious account of native people in North America. Toronto, ON: Doubleday Canada.

Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Kukutai, T. (2004). The problem of defining an ethnic group for public policy: Who is Maori and why does it matter? Social Policy Journal of New Zealand, 23, 86-108.

Little Bear, L. (2000). Jagged worldviews colliding. In M. Battiste (Ed.), Reclaiming Indigenous voice and vision (pp. 77-85). Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

MacQueen, K. M., McLellan, E., Kay, K., & Milstein, B. (1998/2009). Codebook development for team-based qualitative analysis. In K. Krippendorff & M. A. Bock (Eds.), The content analysis reader (pp. 211-219). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Martino, W., & Rezai-Rashti, G. (2013). ‘Gap talk’ and the global rescaling of educational accountability in Canada. Journal of Education Policy, 28(5), 589-611.

Morgan, D. L. (1993). Qualitative content analysis: A guide to paths not taken. Qualitative Health Research, 3(1), 112-121.

Ontario Ministry of Education (OME). (2007a). Ontario First Nation, Métis, and Inuit Education Policy Framework. Retrieved from: http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/aboriginal/fnmiFramework.pdf

Ontario Ministry of Education (OME). (2007b). Building bridges to success for First Nation, Métis and Inuit students. Retrieved from: http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/aboriginal/buildBridges.pdf

Ontario Ministry of Education (OME). (2009). Sound foundations for the road ahead: Fall 2009 progress report on implementation of the Ontario First Nation, Métis, and Inuit education policy framework. Retrieved from: http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/aboriginal/SoundFoundation_RoadAhead.pdf

Ontario Ministry of Education (OME). (2013). A solid foundation: Second progress report on the implementation of the Ontario First Nation, Métis, and Inuit education policy framework. Retrieved from: http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/aboriginal/ASolidFoundation.pdf

Ontario Ministry of Education (OME). (2014). Implementation plan: Ontario First Nation, Métis, and Inuit education policy framework. Retrieved from: http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/aboriginal/OFNImplementationPlan.pdf

Peters, E. J. (2005). Geographies of urban Aboriginal people in Canada: Implications for urban self-government. In M. Murphy (Ed.), Reconfiguring Aboriginal-state relations (pp. 39-76). Montreal, PQ: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Pinto, L. A. (2012). Curriculum reform in Ontario. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Redwing Saunders, S. E., & Hill, S. M. (2007). Native education and in-classroom coalition-building: Factors and models in delivering an equitous authentic education. Canadian Journal of Education, 30(4), 1015-1045.

Restoule, J.-P. (2000). Aboriginal identity: The need for historical and contextual perspectives. Canadian Journal of Native Education, 24(2), 102-112.

Restoule, J.-P., Gruner, S., & Metatawabin, E. (2013). Learning from place: A return to traditional Mushkegowuk ways of knowing. Canadian Journal of Education, 36(2), 68-86.

Tee, N. P. (2008). Education policy rhetoric and reality gap: A reflection. International Journal of Educational Management, 22(6), 595-602.

Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 1(1), 1-40.

Weenie, A. (2008). Curricular theorizing from the periphery. Curriculum Inquiry, 38(5), 545-557.