Ekphrastic

Poetics: Fostering a Curriculum of Ecological Awareness

Through

Poetic Inquiry

Andrejs

Kulnieks

York

University

Kelly

Young

Trent

University

The role of the

imagination is not to resolve, not to point the way, not to improve.

It is to awaken, to disclose the ordinarily unseen, unheard and

unexpected. (Maxine Greene, 1995, p. 28)

Our article emerges from

several knowledge sources as the authors bring together their

experiences of researching and teaching in public and private systems

of education as well as with undergraduate and graduate learners

since 2000. We bring together an interdisciplinary lens to curriculum

theorizing and the importance of developing ecological habits of mind

in teacher education with our research question: “How does one

begin writing a poem that connects language, place, and

intergenerational knowledge?” In teasing out the form, cadence,

and malleable metaphors from an existing story, it is as if the poem

asks the author to clarify the language of the story being

communicated. We read widely in the areas of fiction and poetry,

turning a focus toward an array of aesthetic forms to help deepen our

relationship with language. Playing with form as one begins to write

a poem is essential. By playing with form, we mean immersing oneself

in it. By turning to the poetic form of ekphrastic poetics, an

art form dating back to Classical Greece, we become involved in an

act of poetic response to an aesthetic form through interpretive

practices (Davis, Sumara, & Luce-Kapler, 2000). Interpretive

practices involve building relationships with the aesthetic forms

through, among other things, conditioned writing activities. By

conditioned writing practices we mean (a) spending time in the

natural environments, (b) photographing our local ecosystem, and (c)

drawing upon our memories of immersion in local landscapes and

documenting these in stories/poems as we engage in mimesis.

In his 1595 Defense of

Poetry, Sir Philip Sidney returned to Aristotle’s notion of

mimesis and suggested that poetry is the “art of imitation”

(as cited in Duncan-Jones, 1989, p. 227). Learning to write poetry

involves an immersion in forms, a process of mimesis and the

imagination. Mimesis highlights a complex process of immersion in

forms that can inform an imaginative relationship between writer and

an aesthetic form involving the perception and imagination of the

poet. Poetry, as with other art forms, “is not only a product

of nature, but one of the creative instruments of nature in doing

what it does. We are natura naturans, nature naturing”

(Turner, 1985, p. 46). Etymologically, the word mimesis, from

the Latin imitate-us, refers to a reproduction, a simulation,

and a mimetical fictitious likeness of a phenomenon (The Oxford

English Dictionary, 1989, p. 1378). However, ekphrastic

poetics is more than imitation because it is also about interpreting

self in relation to the ways in which forms are organized. We have

found that by returning to an ancient aesthetic form such as

ekphrastic poetics, we begin to theorize that poetry, as a particular

form of mimesis, organizes human cognition while mediating experience

and identity-formation (David et al., 2000). For language educators,

ekphrastic poetics involves an act of poetic response to an aesthetic

form.

We draw upon mimesis for

the purpose of our work in relation to ekphrasis as it draws our

attention to the organization of the experience, of not only the

practice of paying attention to the natural world in the process of

writing but also the role of photography in this multi-layered

process. For example, taking a photograph while in the natural world

and simultaneously documenting our response to both nature and the

photograph that is revisited over time, involves a poetic response to

an aesthetic form, namely a photograph. However, there is a layered

response as part of the writing process that takes place while in

nature, and an ongoing response to the photograph. This layering is

complex and can lead to a rich response in which mimesis (an

imitation that involves an organization of human cognition), and a

response to an aesthetic form (the photograph) takes place. There is

a rich body of literature on ekphrasis that we consider to be in

keeping with more traditional forms of ekphrastic poetics, which

informs our framework for responding to aesthetic forms through

poetic writing (see Denham, 2010; Heffernan, 2004; Kennedy, 2013;

Prendergast, 2004; and Young, 2006). However, we argue that our

process differs from these works because it involves being in nature

while photographing the aesthetic forms found in the natural world,

and documenting an initial response in addition to a more traditional

poetic response to the photograph taken. This layering provides a

valuable experience for the learner.

We expand our idea of

language learning and interpretation to include opportunities for

readers and writers to observe connections with the places they live

in and know through paying close attention to images. In this

article, ekphrastic poetics is conceptualized as an aesthetic

practice that participates in the ongoing making of human

subjectivities whereby learners can develop relationships between

their ever-evolving senses of self and their engagements with

aesthetic ecological forms. These forms include oral and literary

practices that engage human understandings with what Abram’s

(1996) terms the “more-than-human world.”

One

of the aesthetic forms we feel is particularly important is the

production of collections of works to be shared and remembered in

classroom communities through zines, anthologies, and so forth.

Sharing one’s work with others is an important part of the

writing process. Jan Zwicky’s (2008)

Songs for Relinquishing the Earth is a good example of poetic

art that was first made and distributed by the author herself. Poetic

collections are a good way to help learners develop a sense of what

it means to create poetic work that tells a story. As Debbie Carter

(2011) points out, it is important to have parents and other extended

community members as part of the process. For example, in our

preservice teacher education English/language arts classrooms,

students engage in writing activities over the course of the term.

They are asked to revisit their work and “polish” a piece

to be shared in a class collection. During the last class, we

celebrate their writing through a “literary café”

whereby students are invited to share their writing aloud. It is

wonderful to see how proud students are to see their work in print.

A

Project of Ekphrastic Poetics

Since 2000, we have been

working on a project of ekphrastic poetics. We have been working with

several themes simultaneously, that of intergenerational knowledge

and natural landscapes. As Kucer (2014) points out, “writers

reach their goals by developing a series of plans” (p. 206).

Rather than providing a concrete example of what learners should

model their writing from, we often begin our journey of poetic

inquiry with timed writing activities, designed to take students

toward a research direction of their own choice. If time permits, we

move beyond these preliminary activities to small-group discussions

about the writing activities. Students are invited to continue their

dialogue through electronic technologies (texting, email, etc.) to

further explore their understandings, much as we do in our own

research and poetic inquiry.

We engage with ecological

knowledge from both our foremothers and forefathers as they are

reproduced culturally via intergenerational practices passed down in

the form of stories and culturally aesthetic practices. We are

researchers living in a time of heightened ecological crisis, which

influences us to turn our focus toward aesthetics embedded in the

natural world. Our inclusion of the photo “Mirrored Sunrise”

below is an example of one of the places that we have been developing

a relationship with learning about the indigenous plants and the ways

in which they can be used as medicine both through the collection of

food and teas. We document our understandings through photographs,

conditioned writing practices, and poetry in our practice of

ekphrastic poetics. Not only did we create conditions for poetic

response, but also we paid close attention to our practices. For

example, we use our photographs of the natural world to help

structure and organize our theorization about the ways in which

identity and a sense of self evolve by telling our stories.

We

organized our ekphrastic approach to writing poetry, for the most

part, through timed writing practices, an understanding of mimesis as

an imaginative practice, dwelling in natural environments

(photographing/documenting), and prompted by a notion that one must

become attentive to language. Being attentive to languages and

literacies usually requires that words be clarified and historically

traced in order for a deeper meaning to evolve. For this purpose, the

word organize can be traced back to the Latin word organum

(The Oxford English Dictionary, p. 92). The root of the

word, organ, has a history of being associated with wind

instruments made of pipes that were played in musical harmony.

Organic pipes were assembled into an organized structure and systemic

form. Musical harmony relied on the connectedness and coordination of

its intricate parts. During the 15th century, the meaning

expanded to include body organs. The first body parts identified as

organs were speech organs such as the larynx, which is a means of

communication. Later, an expansive understanding of this word

included any instrument or medium of communication. The word

instrument and the word instruct have the same roots. From these

historical definitions, the verb organize is related to structural

forms, (both the parts and the whole working in harmony) and

instruction (that includes learning through communication via bodily

organs). We draw on this definition to further understand how the

interconnectedness of language (both in the form of visual culture

that is dominated by media and textual representation) and

identity-formation (of a sense of self), evolves through interpretive

response activities.

By

interpretive response activities, we are referring to spending time

in natural environments, photographing our experiences in order to

allow a poetic response to emerge. For example, the following

Kulnieks (2009) photograph titled, “Mirrored Sunrise”

prompted the poetic response titled, “Myths of Weeds”

below.

Figure 1.

“Mirrored Sunrise” (Kulnieks, 2009)

Myths of Weeds

Deep

in the forest of our minds

sword-shaped

cattail stalks soar westward

soft-fleshed

bulrushes rise above shallow marshlands

where

sleeping willows rest in shadows of water lilies

primrose

attracts night-flying moths

hidden

in small clusters of sumac, milkweed, and wild leek

as

myths of weeds crisscross long stalked Great Burduck

filling

Mother Nature’s pantry in a furtive profusion of versatile

delicacies

time

counted in seasons of food gathered and hunted

soil

tilled by hands stained blue with berries

trees

exchanging our air and energy

water

moving information from faraway times

where

wood cooks the food we eat

uncontaminated

by chemicals with longer names than the food

processed

by your hands that placed seeds into the earth

that

gave life when dreams brought us beyond the places

where

colours were learned through a landscape of life

on

summer days you brought me to the hazelnuts

showed

me how to take away the sting by soaking fingers with saliva

to

where mushrooms peered through earth

and

how to break branches for the fire

transform

roots into flowers

that

return each summer

(Kulnieks

&Young, 2014)

Our poem “Myths of

Weeds” tells a story of the delicateness of the earth and the

importance of planting and gathering food. “Mirrored Sunrise”

captures the colours of the early morning sun as the day begins.

Oliver Sacks (1995) points out, colour “is a sense that

interweaves itself in all our visual experiences and is so central in

our imaginations and memory, our knowledge of the world, our culture

and art” (p. 33). The title of the poetic response, “Myths

of Weeds,” evokes a sense of silent language that embodies the

senses. Abram (1996) writes, “Our own speaking, then, does not

set us outside of the animate landscape but—whether or not we

are aware of it—inscribes us more fully in its chattering,

whispering soundful depths” (p. 80). Language is constituted

both by silence through wordless participation and perceptual

immersion in a silent yet expressive world and by sound through a

poetic production of expressive speech. As Abram (1996) explains,

“Language cannot be genuinely studied or understood in

isolation from the sensuous reverberation and resonance o active

speech” (p. 75). Drawing upon Abram’s understanding of

the sensorial experience, what follows is an example of our

collaborative conditioned writing practices.

Figure

2. “Mushrooms” (Vectīrele, 2014)

Earth

Song

Shadows

under

wind swept dock

reveal

our bodies

ebb

and flow

a

symbolic web

soothed

by summer breeze

beneath

ivy wrapped hills

we

hear a robin’s lullaby

her

mating call over the swollen lake

breaking

the silence for the velvet night

capable

wings floating homeward

far

above the ground soar through the trees

as

she sings a bird song

for Gaia

our earth Goddess

grandmother

walks forest paths

as

she has during spring and fall since childhood

searching

along forest and meadow paths

for

mushrooms, berries and other medicines

they

are part of her literacies

translated

in languages

shapes,

sizes, colour shades, scents

knowing

being essential to life

and

knowing movement along these places was healthy

and you

know where

she

knows where the water is

and

how to help the plants thrive

along

the lakes and streams

where

the clear-cutting scraped the vegetation to earth and rock

(Kulnieks

&Young, 2014)

As Melissa Nelson (2008)

reminds us, “The future of our individual and collective health

and vitality depends on us reclaiming and creating healthy food

traditions” (p. 181). Our collaborative approach to writing

poetry comes from hours of spending time in natural spaces, dialogues

about our understanding of intergenerational knowledge and indigenous

traditional teachings that inform our pedagogical process. “Earth

Song” captures much of our dialogue about the importance of

what our grandmothers knew about natural landscapes, indigenous

plants and medicines, and the importance of intergenerational

knowledge that passes down to us through her stories and recipes.

Grandmother is also a metaphorical symbol that signifies a

regeneration of life.

In

addition to being attentive to language as part of an ekphrastic

approach to writing poetry, we focus on the importance of exploring

local ecologies and the ways in which through the imagination new

understandings are achieved through poetic narratives. As learners,

we relate, sympathize, and identify with aesthetic, textual, and

ecological forms, while participating in the practice of

storytelling; ekphrastic poetics becomes a part of that work.

Learners who make connections to these forms will often feel

comfortable and search for deeper more detailed and meaningful

interpretations as ecology plays an important role in the experience.

Literary theorist, Jonathan Culler (1997) understands this response;

he states, “stories, the argument goes, are the main way we

make sense of things, whether in thinking of our lives as a

progression leading somewhere or in telling ourselves what is

happening in the world” (p. 83). Ekphrastic poetics, then,

enables learners to think about their own experiences in new ways and

provides a locale for experiencing the importance of paying attention

to language, the work of interpretation, and the exploration of the

ecology in natural landscapes. This conceptual activity allows for a

(re)assessment of views, a (re)construction of meanings, and a move

toward imaginative conceptualizations beyond lived experiences as it

fosters a development of ecological habits of mind by reminding us

that we are embedded and interconnected with our local ecosystem.

Our final example,

“Grandmother Poem” is an example of poetic inquiry as it

traces a journey, as research participant, towards a deeper

understanding of developing a relationship with a particular place in

Southern Ontario.

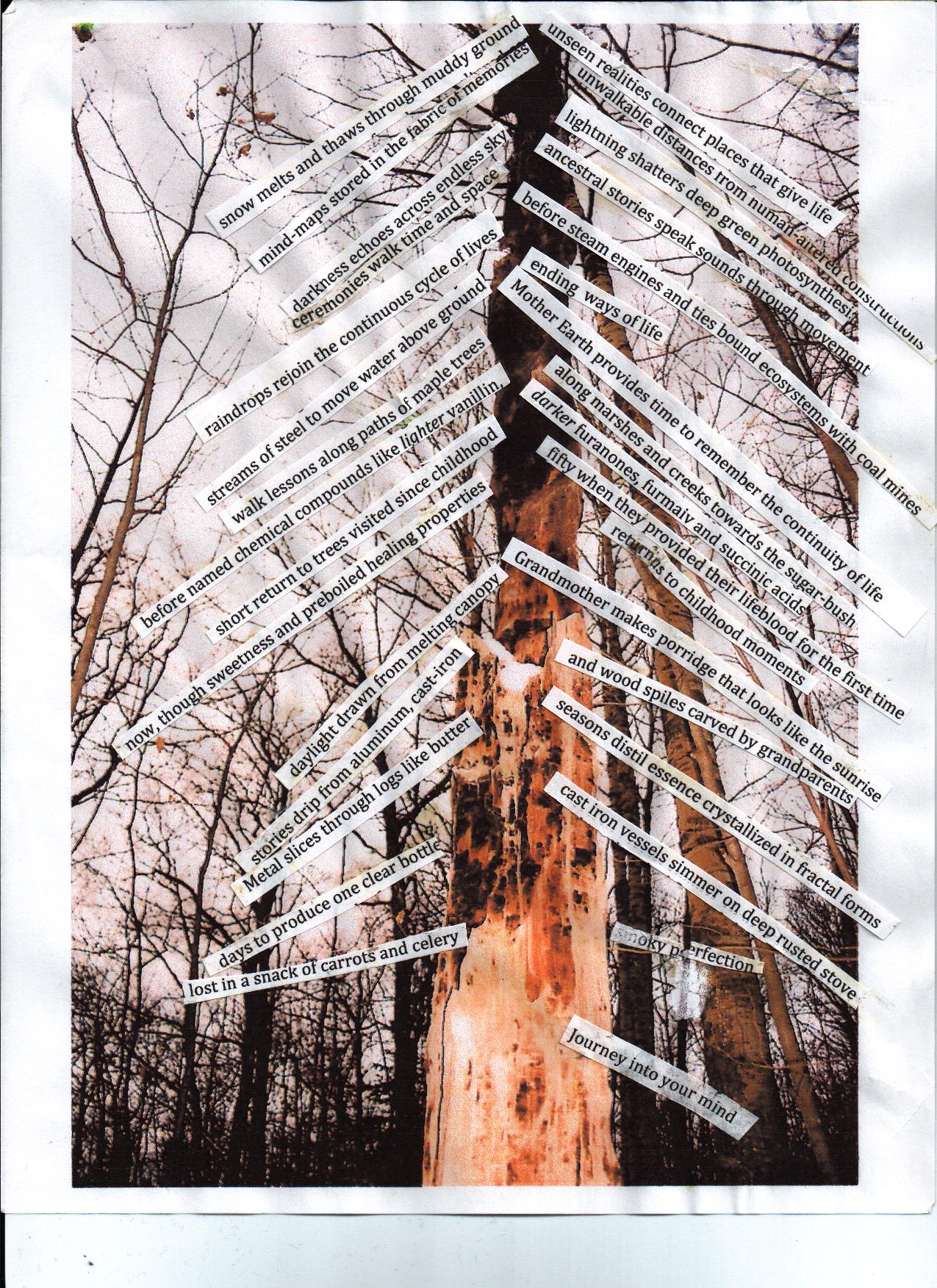

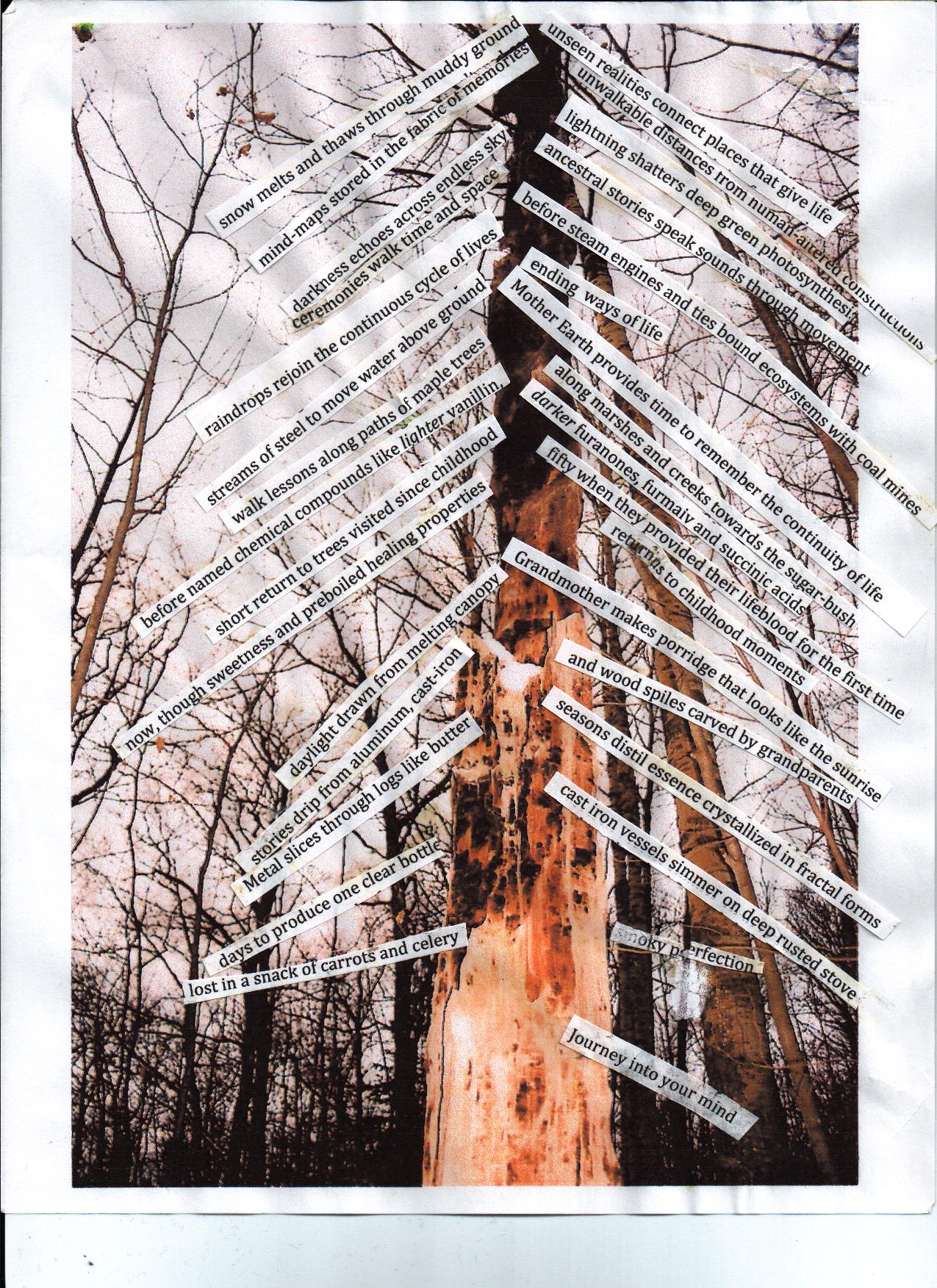

Figure

3.“Grandmother Poem” (Kulnieks, 2012)

In the “Grandmother

Poem,” Kulnieks (2012) traces a journey of learning how to make

maple syrup as an investigation of exploring intact ecosystems. This

poem began as part of an environmental autobiography many years ago.

We have used this poem in graduate and undergraduate classes as well

as during conference presentations as an example of developing a

connection between images and place as a beginning space for poetic

inquiry. The poem began as an inquiry into considering ancestral

teachings about place and plants but evolved into research

specifically regarding how maple syrup is made. It includes the

chemicals that the maple syrup contains. The visual representation

also outlines the cyclical transformation of life. In addition to

birth and rebirth, the language that comes from the branches suggests

human engagement with natural elements, for example, the dead tree.

The fire imagery associated with the ancient scorched tree-trunk also

points to the transformation of the tree that takes place beyond

human use. The poem is an example of bringing images and poetry

together. Through this process, we draw upon Linda Lambo and Tammy

Ryan’s (2012) research about how photography can be used in the

classroom to inspire the development of language researching and

learning opportunities for students: “Families, many of whom

had not actively participated in school functions before, brought

favourite foods, read each other’s albums, and shared personal

stories” (p. 100). This sharing of information in a picnic

format is a way of enabling learners to make connection between their

language learning and the world beyond the classroom. Connecting

classroom learning about nutrition with poetic writing can also

inspire an interest in the types of foods and eating habits that

students and parents engage with throughout their lives by

emphasizing the importance of ecology and intergenerational knowledge

in learning environments.

Ekphrastic

Poetics in Teacher Education: Implications for Pedagogy

We introduce the

classical form of ekphrastic poetics in our teacher education

classrooms framed by a discussion of the ways in which aesthetic

cultural forms and the natural world play an integral part in

organizing subjectivity. We model and participate in classroom

writing practices in order that students have an opportunity to

develop strong poetic habits of mind and perhaps to share these in

their own classrooms. We encourage a dialogue about the ways in which

poetry is linked to the imagination through mimesis. Mimesis, as the

art of imitation, is an important part of pedagogical practices in

terms of spending time observing one’s surroundings. It serves

as the basis for all learning: paying attention to what we are seeing

around us. Mimesis symbolizes the surprising steps that can be taken

along a path in becoming a stronger writer and teacher. By drawing on

William Pinar’s (1995) conceptualization of “curriculum

as aesthetic text,” we become aware of the ways in which the

imagination is provoked through an affective response to visual

senses. In this way, deep emotional resonance can be evoked through

what artist educator, Elliot Eisner (as cited in Pinar, 1985) refers

to as “four senses in which teaching can be considered an art”

which we apply to the creation of eco-poetic work (p. 581). First, as

a teacher of poetry, one should be accomplished in their craft

because the role of artist and educator are inseparable and embodied.

Second, as a teacher of poetry, we make judgements during the

teaching process based on qualities discerned during the course of

the process. Third, as artist and educator, we balance what Eisner

terms “automacy and inventiveness” (as cited in Pinar,

1985, p. 581) through different weekly writing exercises along a

continuum of inquiry into learning to write poetry. Eisner suggests

that it is the teacher who must model pedagogical practices that

provoke the possibility of surprise in teaching and learning.

Finally, there must be a balance of “routinized behaviours”

(as cited in Pinar, 1985, p. 581) with creativity in the classroom.

It is essential to create the conditions that evoke the imagination

in pedagogical settings. In Pinar’s (1995) words:

To

understand the role of the imagination in the development of the

intellect, to cultivate the capacity to know aesthetically, to

comprehend the teacher and his or her work as inherently aesthetic:

these are among aspirations of that scholarship which seeks to

understand curriculum as aesthetic text. (p. 604)

We

conceptualize the work of ekphrastic poetics as a curriculum and

aesthetic-ecological text. By introducing new forms into teacher

education classrooms such as ekphrastic poetics, learners can develop

relationships between their ever-evolving senses of self and their

engagements with natural aesthetic forms.

To

answer our question that we posed at the beginning, “How

does one begin writing a poem that connects language, place and

intergenerational knowledge?”, we have

turned our attention to ekphrastic poetics, a classical art form, and

theorized its importance as a literary form. We have ascribed to the

notion that forms function to organize experiences of

identity-formation. The answer lies in the way in which this notion

of poetry is framed. Aesthetic forms are inherently organizing

phenomena that are often inspired by the natural world. By pointing

to our own example of engaging in ekphrastic poetics, together with

the ways in which we introduce this classical form in our teacher

education classrooms, we are opening possibilities of using literary

forms in the exploration of the ways in which forms organize and

mediate human subjectivities. In this way, responding to

visual culture involves paying attention to the natural environment,

language, mimesis, the imagination, and the affective response they

provoke through conditioned interpretive practices. Just as humans

can form relationships with particular literary forms, they can form

relationships with visual and natural forms. These relationships are

important as they inform pedagogical practices and provide insight

into research about our connections with local environments.

The

close study of works of visual and natural relationships with intact

ecosystems is important and by carefully working with one idea, such

as ekphrastic poetics, new details can surface and consequently a new

outlook can be evoked. Forms are influential in the ways learners

experience identity and the particularity of ekphrastic poetics is

interesting and relates not only to language but also to

representational forms and lived experience. Since humans need forms

to help them organize a sense of self, interpretative practices with

ekphrastic poetics provide learners with a form to negotiate a sense

of self in relation to the world. Keeping in mind that, according to

Bruner (1990), this self finds itself lodged in the

cultural-historical situation as well as in the private

consciousness, forms are mediated and organized by language. Poetry

organizes human consciousness in particular ways, and ekphrastic

poetics can become one form that organizes perception and helps to

foster ecological habits of mind in teacher education.

References

Abram, D. (1996). The

spell of the sensuous: Perception in a more-than-human world. New

York, NY: Pantheon Books.

Bruner,

J. (1990). Acts of meaning. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University

Press.

Carter,

D. (2011). Teachers' voices: Welcoming family collaboration. In R.

Powell & E. Rightmyer (Eds.), Literacy for all students: An

instructional framework for closing the gap (pp. 71-85). New

York, NY: Routledge: Taylor & Francis.

Culler,

J. (1997). Literary theory: A very short introduction. New

York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Davis,

B., Sumara, D., & Luce-Kapler, R. (2000). Engaging minds:

Learning and teaching in a complex world. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence

Erlbaum Associates.

Denham,

R. D. (2010). Poets on painting: A bibliography. Jefferson,

NC: McFarland.

Duncan-Jones,

K. (Ed.). (1989). Sir Philip Sidney: A critical edition of the

major works. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Greene,

M. (1995). Releasing the imagination: Essays on education, the

arts, and social change. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass

Publishers.

Heffernan,

J. A. (2004). Museum of words: The poetics of ekphrasis from Homer

to Ashbery. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Kennedy,

D. (2013). The ekphrastic encounter in contemporary British poetry

and elsewhere. Farnham, UK: Ashgate.

Kucer,

S. (2014). Dimensions of literacy: A conceptual base for teaching

reading and writing in school settings. New York, NY: Routledge,

Taylor and Francis.

Kulnieks,

A. (2009). Ecopoetics and the epistemology of landscape:

Interpreting Indigenous and Latvian ancestral ontologies.

Toronto, ON: York University. Unpublished Dissertation.

Kulnieks,

A. (2012). Grandmother poem. Rampike, 21(1), p. 79

Poetics: Part One.

Kulnieks,

A., & Young, K. (2014). Ekphrastic poetics: Reflecting poetry

beyond images. Unpublished Manuscript.

Lambo,

L. & Ryan, T. (2012). Traversing the "literacies"

landscape: A semiotic perspective on early literacy acquisition and

digital literacies instruction. In E. Baker (Ed.), The new

literacies: Multiple perspectives on research and practice (pp.

88-105). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Nelson,

M. (2008). Original instructions: Indigenous teachings for a

sustainable future. Rochester, VT: Bear & Company Publishers.

Organize.

(1989). In the Oxford English Dictionary. London, England:

Oxford University Press.

Prendergast,

M. (2004). Ekphrasis

and inquiry: Artful writing on arts-based topics in educational

research.

Proceedings

from the Second International Imagination in Education Research Group

Conference, Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, British Columbia.

Retrieved from

http://www.indabook.org/preview/lTBabTVl6DXtk-K9jf8G5Rf9maQmqkGgUFVuHfgJf2I,/EKPHRASIS-AND-INQUIRY-ARTFUL-WRITING-ON-ARTS.html?query=Inquiry-Based-Topics

Pinar,

W. (1995). Understanding curriculum. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Sacks,

O. (1995). An anthropologist on Mars. New York, NY: Random

House.

Turner,

F. (1985, August). Cultivating the American garden: Toward a secular

view of nature. Harper's Magazine, 45-52.

Vectīrele,

Z. (2014). Free Entrance: Collecting stories through photographs.

Unpublished Manuscript.

Young,

K. (2006). The pedagogic force of ekphrastic poetics. Language and

Literacy: A Canadian E-Journal, 8(2), 1-18.

Zwicky,

J. (2008). Songs for relinquishing the earth. London, ON:

Brick Books.