The Radiance of the Small

Alexandra Fidyk, University of Alberta

Lorri Neilsen Glenn, Mount Saint Vincent University

Merle Nudelman

We are surrounded by paradoxes—in darkness, light; inside despair, courage. Truth speaks and yet often we do not hear. Mystery beckons to be known but we cannot perceive it until we open to our connection with the larger world.

Do we strive to live consciously and intimately with the natural world, in harmony with the transcendence and tragedy that whirl in its rhythms? We perceive the slim line between here and not here, the inevitability of losses. This is the challenge and a conundrum: to integrate within ourselves the dark/light cycles of the natural world, yet flourish in times of grief and pain. But how does one lose and be grateful? How do we create harmony between body and soul?

Here we explore the lessons of a snail wedded to the earth, astute in its slowness, in its minute shadow; we listen for the small-throated life; we adopt the unapologetic, razor eyes of the raven.

Merle:

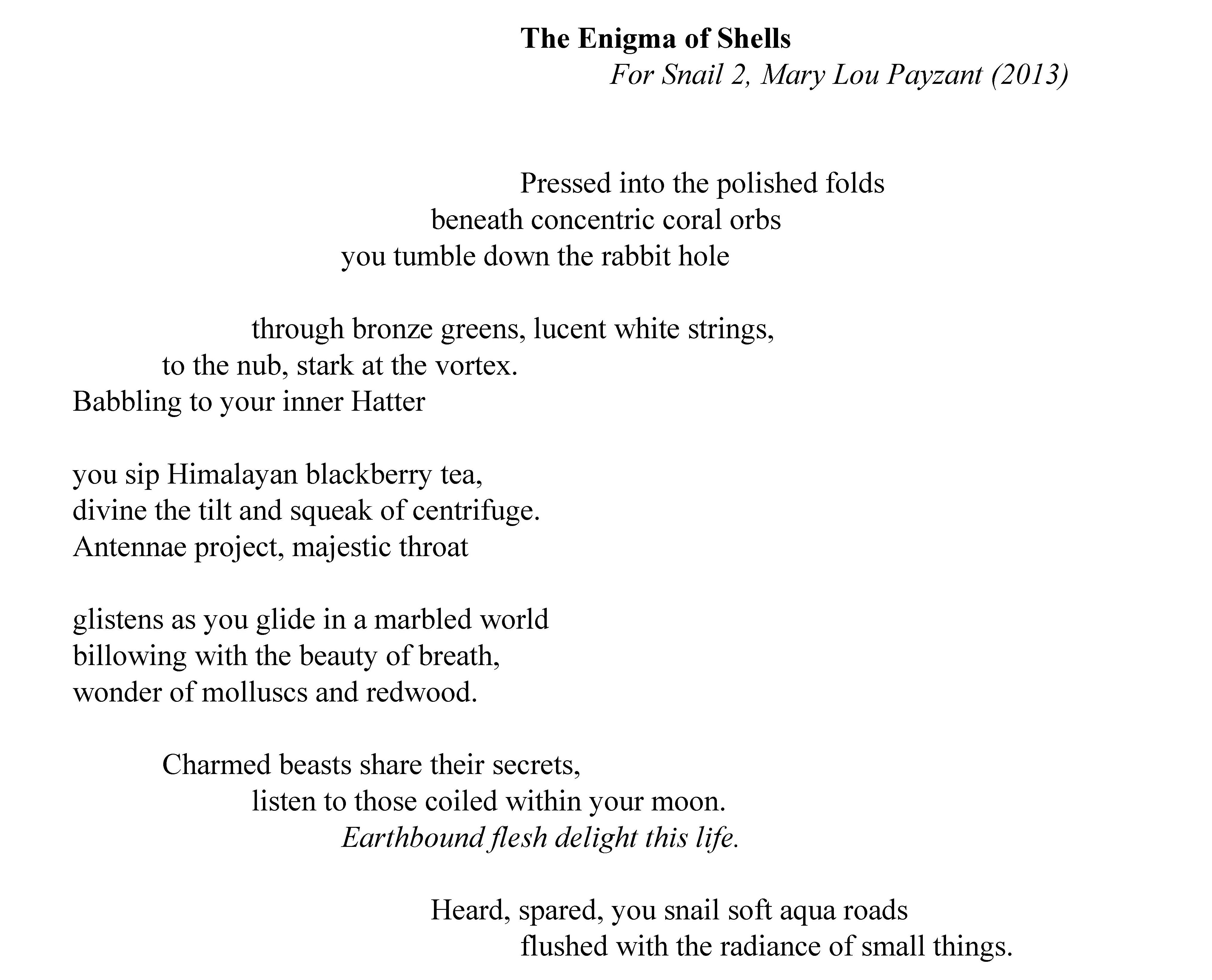

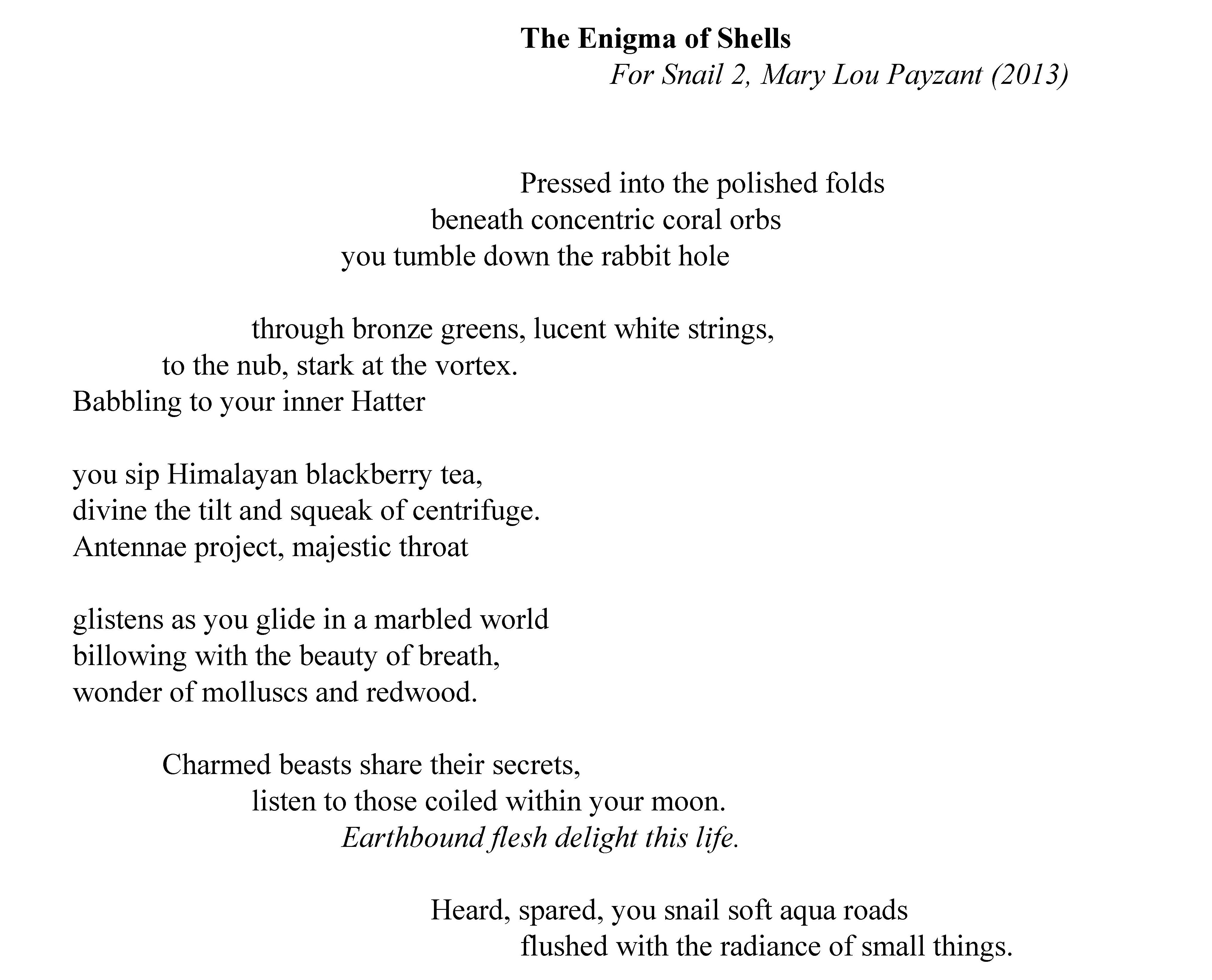

During a period of severe ill health, I chose to ground myself and expand my focus by writing poems crafted in response to paintings created by studio artists of the Women’s Art Association of Canada. Visual art coaxed me away from rational analysis and eased me down into the tunnel winding towards the subconscious and intuition. Why such a suffering darkness? What were the lessons to be culled and cherished in the glow of healing? The poems evoked some answers but I intuited that there was a deeper knowing to be extracted from this process.

In the fourth poem of this series, the beauty of simplicity appeared. Profound truths reside in the rings of a snail's smooth shell.

What would this particular poem tell me if I entered each line closely? Baring my heart to the poem, I swam into the well of each word and listened for the echoes.

Pressed into the polished folds / beneath concentric coral orbs

Boneless and pliable after the onslaught of illness, you search for a cure in unexpected places, slot your struggles within available glib and easy meanings – the deceptively optimistic loops spinning inside loops and revealing nothing.

you tumble down the rabbit hole

Emotion and body out of your placid control, you keep falling deeper into the subterranean darkness beneath the fantasy world of magical solutions.

through bronze greens, lucent white strings / to the nub, stark at the vortex.

You pass through the rooms of your conscious awareness that shelter the naïve, idealized beliefs of the untested and then, finally, you arrive at the core of things and the truths lurking there.

Babbling to your inner Hatter

Mumbling hopeful, intellectual gibberish to yourself, your bored and spiteful mind responds with psychological riddles, which you mutely ponder as you slowly settle into the exhalation of white space.

you sip Himalayan blackberry tea, / divine the tilt and squeak of the centrifuge.

Thoughts calming, you are centered, fully awake. Insight sharpens and speaks through intuitive strands. Clarity, white and pure as divine light, reveals aspects of reality and unreality, axis angles of the karmic wheel of the Universe.

Antennae project, majestic throat / glistens as you glide in a marbled world

Senses and sensitivities are heightened. Awed by the transformative power of the mind and touched by the exquisiteness of this complex world, you fully re-enter life at ease in your body and with your place in the fabric of being.

billowing with the beauty of breath, / wonder of molluscs and redwood.

Free and easy as a sail catching a steady breeze, you rejoice in living and in the miracle of everything.

Charmed beasts share their secrets, / listen to those coiled within your moon.

In response to your gratitude and your nascent wisdom, the sphere of magic opens to you and you, in turn, open to the mystery and release the darkness clutched within your soul.

Earthbound flesh delight this life.

Now the soul is free to speak and advise. At this moment, it says, you are tied to this body, to this material place. That is a gift even with the suffering, even with the sorrow. Peace is yours when you stay wisely aware and dismiss the angered judge with her caustic jury. This is your opportunity to be with courage and to go through the tall doors as they appear. In return, you must bring light to this earth and joy to other beings. This delights all life, including your own.

Heard, spared, you snail soft aqua roads / flushed with the radiance of small things.

Healthful zest restored, you walk with thoughtful gladness amidst the wonders of this realm and find magnificence everywhere even in the tiny snail.

The alchemy between luminous awareness and darkness flickers and burns.

*****

Lorri:

At the peak of the blizzard, I could not see the ocean for white, hear for the howl, but through the windows, snow-edged quilt patches, I could make out dark dots flicking, flicking against the side of the barn.

How do they live? It’s 30 degrees below zero. I opened the latch, and the door flung itself against me in fury. The devil himself roaring his way inside—roaring and tugging at the container of seeds I grasped as I made my way out to the edge of the deck, the air like frigid teeth at my face. I walked as a penguin might, fearful of ice, and then, snow blind, my gait loosened on the sleek surface. Behind me, the door crashed against the inside wall.

I had to throw the seeds. It was not possible to make my way to the bird feeder on the ice in this wind; instead, I swung my arm blindly toward the wall of the barn where I’d seen them. Bits of grain and sunflower seeds swirled, picking at my face, flying upward and out, landing who knows where. Under the white wall, against the dark shape of the building. Flick. Bounce. Under the howling wind, I barely heard the cheeping.

Small-throated life.

I must remember this.

Two months later, winter still pressing us into submission, an email brought my husband startling news. His lifelong friend was in critical condition. It had happened within a day. Janet’s husband updated her friends over email every day for a week, long descriptions of medical procedures, written with the kind of control that comes only from despair wanting voice. The tracheostomy, the steroids, the H1N1 specialist. Up, down; hope, fear. An extended family, a community on tenterhooks—stunned at how slender the line between here, not here; breath, no breath.

Then, the final email: “Her lungs let her down.” My husband booked a flight and gathered with 200 people as shocked as he to sing, look at old photos, exchange stories about a vital, active, creative woman. A life slammed shut as rapidly as a door in a fierce wind.

Small-throated life. Its radiance. The startling force of its tender presence. Absence, presence: I learn each day how thin the veil is.

To echo and rephrase Merle’s question: What can I learn if I enter each of these moments closely?

We tend to live large and noisy in the busy containers of our worlds—at least I do. And, caught up with shallow urgencies, I become largely unaware, deaf to the small-throated. I’ve known since I was a child I am mortal, but I also know in the middle of life, it’s easy to dull this awareness. It’s the suddenness of a death such as Janet’s that brings me back to the radiance of the small.

Years ago, during a decade of losses, as I studied the desert fathers’ work, along with the words of a wealth of scholars, theologians, and poets on faith and the spirit, I began to learn what poet Elizabeth Bishop (1977) calls the “art of losing.” As she wrote: “So many things are filled with the intent to be lost that their loss is no disaster” (Bishop, 1977, line 2) She is writing ironically, of course: the poem, “One Art” is a villanelle, a structure enabling her to contain her tears. It speaks eloquently of the profound effects—the depth charges—of loss. I believe one’s life work, as I have written elsewhere, is learning to lose. Learning to let go and to wave goodbye to our losses with deep gratitude for their gifts.

But the small-throated. Bird sounds in a blizzard: the radiance of the small. A single movement on the surface. I’ve learned how the force of life impels, resists being extinguished. How in the long winters of my life it’s important I work at being aware of my own and others’ presence, their bodily selves. Close enough to hear them call, even if I cannot see or feel them.

*****

Alexandra:

A black Raven came to my door years ago

and flew away one spring.

He returned on Christmas, the first thing

I saw out my steamed morning window.

(It was not the gift I had imagined.)

Sentinel pines, still northern lake,

haunting silence –

a Saskatchewan winter.

And there –

against the frozen white,

against the freeze frame of lake, its vast expense,

white against white, adorned, encased

by the glitter of hoarfrost,

his shining blue-black feathers

radiant with life sheen, betrayed

this harsh place.

Its unbearable-ness.

Its arduous survival. Life, suspended.

He hops on the snow-packed earth, stealing

bits of this and that, scraps unseen

by any other eye,

divining the story of this land.

The Raven is no ordinary bird.

There is something ancient and distinguished about a raven: mischievous trickster, acrobat and skillful master of flight, harbinger of death and the knowing eye.

Across cultures and history, stories confirm the relationship between human and raven: it is an ancient pairing. When we were nomadic peoples, we revered ravens as companions “who inspired poets and engendered creation myths” (Heinrich, 1999, p. 145). Marija Gimbutas (1989) describes our mythological relationship through the Celtic shape-shifting goddess of death, the Morrigan, who appears as “a hag, a beautiful woman, or a raven” (p. 189). In Germanic mythology the Valkyrie, the beautiful attendants to Odin, the god of war, poetry and wisdom, are identified with “the raven, the dark bird of the dead” (Gimbutas, 1989, p. 189). In both references, raven’s association is to woman; together they signal a fate. Such descriptions locate this winged familiar in the ink-black darkness of life.

This bird—its arrival, departure, and return—has storied my life. Like the barren Saskatchewan winter-scape framed against the presence of this messenger, my fate—a chronic neurological illness that plunged me sharply into aging—stripped me to the bone. It cut me small and turned me “to the nub, stark at the vortex.” A defeat of “I,” not the relinquishing of ego-centeredness common to midlife, but a shattering of the organizer and container of the self. This stripping included the collapse of organs, spawning of tumors, degeneration of vertebrae and jaw, and contamination of blood. Vital centres of my brain—those responsible for memory, personality, emotions and complex functioning—atrophied. Burnt up. In the demise of the matrix of cellular interconnectivity, memories dissolved, relationships died. Imagination, curiosity, joy, patience, relatedness, life force—all disappeared.

Then the greatest theft: words. The winged trickster famed for both the gifts of communication (oratory, poetry, and alphabet) and silence, stole their magic and meaning, leaving no-thing in return. With the loss of my ability to read and write, I lost hold of life as it was known. Life, suspended.

Naked, a body remained—empty and still. Weeks passed into months. Months passed into years. There was no re-entry into life, no ease with the body. This was not a heroine’s journey.

Five years of intensive treatment and words have begun to return. To an outer eye, I have resumed a recognizable life. But the curvature of my day remains wed to the life-and-death cycle of the invading spirochete. While I no longer dwell in the darkest crevices of the underworld, like those who have eaten of the red pomegranate, this place of suspension is now home. While the blackest of black has waned to dark blue, the depth of the former blackness has not disappeared. Just as the loss of a loved one never vanishes—the “blue is ‘darkness made visible’” (Hillman, n.d., p. 37). Cloaked in blue-black, Raven remains my companion.

Not every descent swings upward. The heroine returns from the night-sea journey in better shape for the tasks of life. She has endured and so she returns en-lightened. Nekyia is another journey entirely. The land of “Blacker than Black” (Hillman, 1997, p. 50) swallows the “soul into a depth for its own sake so that there is no return” (Hillman, 1979, p. 168). The night-sea journey common to midlife is marked by an increasing inner intensity, a fire within that burns away rigid patterns. This fallow ground is where light gets in. Nekyia, however, sinks “below that pressurized containment, that tempering of the fires of passion, to a zone of utter coldness” (Hillman, 1979, p. 168). Descent to the underworld. Of this journey, there is no return. No homeward turn.

Hades is the ultimate dissolver of the luminous world. Each moment of blackening is the “harbinger of alteration, of invisible discovery, and of dissolution of attachments to whatever has been taken as truth and reality” (Hillman, 1997, p. 49). Black darkens and sophisticates the eye so that it can see through. Alchemists call this work the caput mortuum, death head or raven’s head. It requires both a living through and a seeing through death and loss and sorrow. “The principle of the art is the raven” (Jung, 1963/1989, para 37). To see by means of black. To live by the Raven’s eye. And to be at home in suffering.

*****

“What can we learn if we enter each of these moments closely?”

We are both larger and smaller than we had imagined. Offering this awareness we make peace

with death which resides inside each life and with a life that stretches beyond death.

References

Bishop, E. (1977). One art. (From Farrar, Straus, & Giroux, 1983, The Complete Poems 1926-1979). Reproduced online at http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/176996

Gimbutas, M. (1989). The language of the goddess. San Francisco, CA: Harper & Row.

Hillman, J. (n.d.). Alchemical blue and the unio mentalis. Retrieved from http://www.pantheatre.com/pdf/6-reading-list-JH-blue.pdf

Heinrich, B. (1999). Mind of the raven. New York, NY: Cliff Street Books.

Hillman, J. (1979). The dream and the underworld. New York, NY: Avon.

Hillman, J. (1997). The seduction of black. In S. Marlan (Ed.), Fire in the stone: The alchemy of desire (pp. 42-53). Wilmette, IL: Chiron.

Jung, C. G. (1963/1989). The paradoxa. In Mysterium Coniunctionis. The Collected Works of C. G. (Jung. (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.), volume 14, (pp. 42-88). Bollingen Series. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Payzant, M. L. (2013). Snail 2. Acrylic on canvas, 8" x 10."