“The Receiver No Longer Holds the Sound”: Parents, Poetry, and the Voices We Create in the World

Heather McLeod, Memorial University, and Gisela Ruebsaat

In this paper, we explore how poetic inquiry (Brady, 2009; Prendergast, 2009; Butler-Kisber, 2012) informed by duoethnography (Sawyer & Norris, 2013) enables us to know our parents better and to reflect on our relationships with them after their deaths (Leggo, 2010; Stewart, 2010). We are interested in how this process of inquiry deepens our thinking about the nature of research and writing as well as about teaching and community work. We believe that self-study can be linked to teaching for social justice; by studying our own practices we can begin to comprehend our potential marginalization of others (Bride, as cited in Mcleod, 2011). By unearthing the roots of our own professional voices through a process of writing as personal inquiry, we are in a better position to ask: How does the voice we use in the classroom or other professional contexts affect our students/listeners/readers? If we adopt a detached professional mantle are we unconsciously attaching a higher rank to a particular style/form of narrative? By making our narrative choices conscious, can we create a safe space, a more level playing field, which invites other players in? As noted by Wiebe and Snowber (2012), a notion of “professionalism” implies that the personal and the professional cannot coexist; teachers have control in the classroom and the personal should not interfere because it has nothing to add. Wiebe and Snowber argue that in poetry there is a way to resist retreating to the security of our public roles, and to challenge paradigms of personal exclusion with honesty. Through the process of poetic inquiry we engage with our personal stories. By working with the images embedded in these stories, we potentially pave the way for more subtle narratives to emerge and be heard, both for ourselves and for our students/listeners/readers. As Wiebe and Snowber (2012) suggest, “If one cannot hear the interior quakes of a life, it is very difficult to hear the quakes and questions of our students” (p. 459). By modelling a process of personal inquiry, we also encourage our students/listeners/readers to engage in their own processes of inquiry, and thereby, to support the development and expression of their own voices, a key building block of learning.

Sources for our work include the poetry of Heather’s father. which four decades after his early death at age 43 is still preserved by the family but remains unpublished. For him, writing poetry seems to have been a way of charting, commenting, and thinking through the vicissitudes of his lived experience (Soutar-Hynes, 2012). Other sources include Gisela’s interviews with her mother before her death and anecdotes her mother told Gisela as she was growing up. These were vignettes about war, death, migration, and survival, threads now interwoven with Gisela’s memories of her mother and now informing Gisela’s work with victims of violence. (Ruebsaat, 2009a, 2009b, 2013a, 2013b).

Poetic inquiry is a new, imaginative, and innovative research initiative. It enables “magnified encounters with life as lived, up close and personal” (Brady, 2009, p. 12). The poetic speaks out in everyday life in its lived language. Poetry is, in a sense, a more direct kind of research: “Instead of writing through abstract concepts…poets write in and with the facts and frameworks of what they see in themselves in relation to others, in particular landscapes, emotional and social situations” (Brady, 2009, p. 15).

Prendergast (2009) argues that poetic inquiries tend to belong to a category distinguished by the voice that is engaged. Our work is a combination of two such categories: (a) Vox Autobiographia/Autoethnographia or researcher voiced poems with the data sources, including reflective/creative/autobiographical/autoethnographical writing and/or field notes and journal entries (Gisela writing about stories from her mother); and (b) Vox Partcipare or participant voiced poems written from interview transcripts or solicited directly from participants (Heather’s father’s poems).

Gisela is interested in how her family history and poetic voice inform her social justice work in the legal milieu dealing with violence against women. By engaging in poetic inquiry, she acknowledges the power of personal narrative to effect social change. Traditional legal discourse relies on abstract language and the use of logical argument. As a legal analyst conducting interdisciplinary social action research that calls for active engagement, she finds the question of voice and resonance critical. Without embodied language, which evokes emotion and draws the reader in, key elements of the story are rendered invisible. The naked human voice and its persuasive power in the narrative are lost. Certain forms of knowledge are best evoked through image or metaphor. These subtle threads will disappear from the discourse if it relies primarily on direct authoritative statements made by a dispassionate observer. Boughn (2013) discusses poetry as a linguistic mode of knowledge in which knowing is multiple, diverse, dynamic, and layered simultaneously. Poetic inquiry reminds us that aesthetic choices are, in fact, political choices. The importance of personal story—the individual voice speaking in its everyday cadence—is slowly gaining recognition in the legal community, with fiction writers training lawyers on the art of persuasion using literary writing techniques.

Through the lens of poetry, we have been able to see beyond the received family histories of whom our parents were and to fashion a more layered and nuanced picture not only of them but also of the social forces that shaped them, and in turn shaped us as researchers and social activists. War, class, and gender were significant factors that moulded our parents’ lives in different ways. We have structured our paper to reflect our dialogue. Further, we acknowledge that the creations arising from our research dialogue are, in the end, our stories about our parents (Leggo, 2010).

The current iteration of our project draws on the practice of duoethnography (Sawyer & Norris, 2013). Duoethnography views life history as an informal curriculum and sees meaning, not as a static element, but rather as something that is explored and created through dialogue with the research partner. Duoethnographers select a theme to investigate and, working in tandem, engage in a process of data analysis (with the data often including cultural artifacts from their lives), and abduction, or imaginative thinking about the data. In some cases the dialogue between the researchers is made explicit through the publication of transcripts. Duoethnographers juxtapose narratives of difference to examine and open new perspectives and experience. Sawyer and Norris (2013) argue that “Generative detail is found in description, not explication; in questions, not definitive statements; and in story, not abstract understandings” (p 43). Further, they argue “The goal is to present sufficient thick descriptive detail-showing not telling-to allow the reader to engage imaginatively in and be altered by the conversation” (Sawyer & Norris, 2013, p. 46). The dialogue in duoethnography is not only between researchers but also between researchers and their perceptions of cultural artefacts from their lives including stories, memories, compositions, and critical incidents. By examining personal and cultural artefacts and by engaging in collaborative critique, duoethnographers make their assumptions and perspectives explicit. By writing in the first person and avoiding the abstract authoritative voice, duoethnographers invite readers into the conversation. Sections of their study may be written in script format, alternating between speakers.

Duoethnography was a good fit for us in part because of our long-standing friendship. Our process involved long walks and open-ended conversations. We continued this synergy via our writing process in which one of us would write a portion, and then the other would write a portion, so our dialogue continued back and forth. We both used some existing poems as the springboard or data sources for the dialogue and analysis as well as our own personal histories as further context or framework.

Duoethnography is nested within a conception of how narratives work within the broader culture (Sawyer & Norris, 2013). As Said (1993) has argued, “The power to narrate, or to block other narratives from forming and emerging, is very important to culture and imperialism, and constitutes one of the main connections between them” (pp. xii-xiii). Thus, a commitment to social justice may involve critical self-analysis of the internalization of colonialism, domination, and unjust discourses. Sawyer and Norris (2013) call for a process whereby educators become conscious of the internalization of oppression. They note that even educators working from a social justice perspective, might be engaged in action to the detriment of personal reflection and analysis. Thus, without being aware of it, we risk re-enacting oppressive narratives. However, personal reflection and analysis can allow action to be informed, discourse reframed, and language reconsidered.

Additionally, Said’s (1993) notion of the power to narrate and the connection to culture and dominance is fruitful when thinking about our families of origin. Self-analysis of the internalization of domination leads us to question who within our families composed the dominant narrative. Pelias (2008) writes, “Families are often delicately balanced systems, constructed through carefully made scripts and written in codes for use both within and outside their walls” (p. 1311). In Gisela’s family culture there was a lead voice that set the tone and created a hierarchical structure based on age, gender, and level of education attained. This structure determined both who and what was heard. Very limited space was created to encourage younger or more tentative voices to emerge. These other voices would be included in the family narrative only to the extent that their musical line harmonized flawlessly with the dominant melody. Jazz-like forms and extemporaneous improvisation were not part of the structure. Silences, gestures, and other subtle forms of communication were not given prominence. Therefore, seeking balance, Gisela explored her mother’s anecdotes—which were often fragmentary or elliptical. For Heather, it was worth examining her father’s poetic narrative from an adult perspective. This narrative was only known to Heather in her youth and was almost forgotten. Her father’s poems created a window, a glimpse, into Donald’s world and his voice within that world.

In our exploration of the development of voice within larger family and cultural narratives, we took somewhat different approaches. Heather examined her father’s words—the poetry he wrote over a lifetime. This is the direct voice at a particular moment. Gisela explored whom her mother was by writing poems based on her mother’s remembered stories or based on images created from fragments of stories Gisela heard after her mother’s death. This is construction through memory. Helpful to us is Stewart’s (2010) conception of language as “mothertongue,” a notion that “burrows into the layers of our complex relationship with language, created through our cultural and social histories, begun with a relationship with a parent or parents, held in our bodies, and present in our voices” (Stewart, 2010, p. 88).

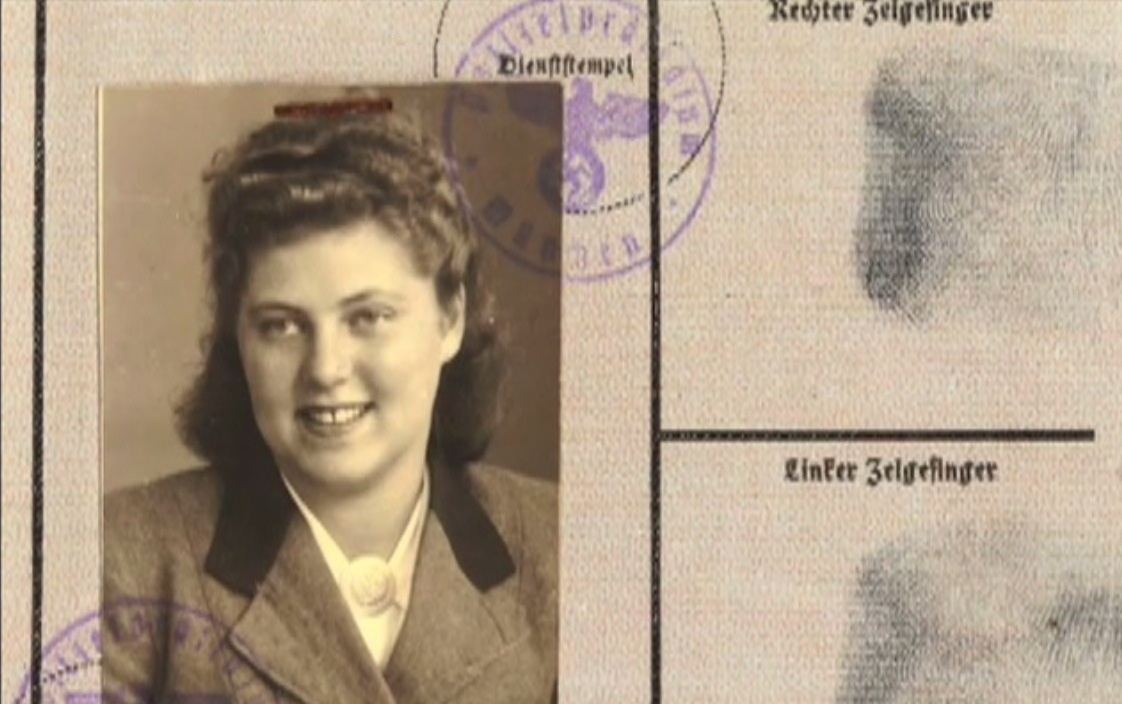

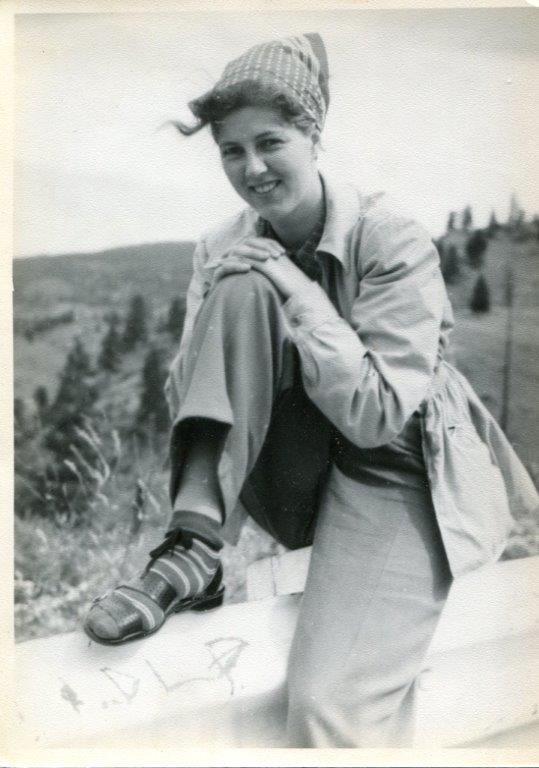

Heather’s father, Donald McLeod, and Gisela’s mother, Ursula Schumacher, were born in the late 1920s and were teenagers during the Second World War. Later, as adults, they both lived in British Columbia, Canada. They never met. Their voices were marginalized: Donald’s through the operations of class, regional disparity, and ultimately by his early death; and Ursula’s through the inequities associated with gender, language, and immigration status. Nevertheless, they strove to reach beyond their marginalization through the acquisition of education and language.

Rebellion/Leadership—Gisela

My mother was the oldest of the three Schumacher girls. Her father taught math and physical education at a boys’ school in Nazi Germany. The Schumachers lived in a tiny farming community on the shores of the Rhine. There were no boys in the family. Before the war, my grandfather taught my mother and her two younger sisters to swim in the river. My grandmother never went in the water. She never appeared in a bathing suit. The Rhine is a dangerous place, romantic, wild, with unpredictable currents and murky water. As a math teacher, my grandfather tried to instil in his daughters a respect for authority. As a physical education teacher, though, he taught them that timidity was not the route to safety. Instead, they should rely on their own strength and ingenuity, and their physical prowess, as the means to survival. For my mother, this teaching was translated into a particular form of leadership:

Schumi’s Turn

The clock strikes in my Aunt Hedwig’s house in Bonn.

We drink dark afternoon coffee, eat apricot torte.

My Aunt serves and Gertrude lifts her cup from its saucer,

tells me about my mother at school:

This nun would line us up, our palms open

as if to receive the communion wafer then

whack us one by one with a stick.

We all pulled our hands back

as she stood before us that black spectre.

It was just before The War.

Schumi’s turn comes, your mother,

she is quick, she runs from the line-up

here, there everywhere

in and out of rows all around the classroom

knocks over desks as she turns

the nun must give chase, her habit askew

your mother’s blond curls fly.

The rest of us stay in line,

press our lips together, hold our breath to bursting

bubbles of laughter escape our throats

to join Schumi in flight.

Gertude puts her coffee cup down on the saucer she still holds,

that porcelain sound in this living room now.

My Aunt joins us, shakes her head slow, smiles

offers more torte.

A late sun bounces back from the hall mirror

I squint as rays hit my face

apricots sit on my tongue.

Voice for Justice—Heather

In Canada, my father was a teenager with a predisposition to the literary arts. In the early 1940s, he was enthusiastic about moving from rural Manitoba to Victoria, BC, which was possible because in wartime my grandfather’s skills as an electrician were in demand for shipbuilding. In contrast, during my father’s childhood his family had barely survived the unemployment and poverty of the Great Depression with the aid of a relief settlement plan, which saw over 7000 city-dwelling Canadian families toiling on rural farms (Struthers, 1983). Perhaps because of these experiences, my father was always attuned to injustice. In this he may have followed the lead of his mother, who had contested government policies on the steps of Manitoba’s provincial legislature in Winnipeg. Despite having only attained a Grade 3 education, in later years, she expressed herself in rhyming verse some of which involved social protest.

In Victoria, the transition from a rural one-room school to a city school with subject specialist teachers was fascinating for my father and he took a leadership role in the school newspaper. In 1945 as a Grade 9 student he wrote the following condemnation of graft and government corruption. Despite his mother’s interest in social justice, his parents were not explicitly political and my father would not have been exposed to the radical press. A messy pencilled scrawl on a piece of now-fragile lined paper with only a few edits, the untitled poem (here slightly edited) does not appear to have been written as a school assignment. It seems that Donald begins at the end of World War I and concludes with the end of World War II, collapsing the economic distress of the 1930s in Canada into a murderous but nevertheless, perhaps understandable, social rebellion. My father’s emerging voice reflects the zeitgeist of the times and a feeling of what it was to be an enraged 15-year-old appalled by the momentous world events of 1945.

The summer and autumn had ended the war

And in the winter t’was no peace yet

It was a piteous sight to see all around

Men lie rotting the world around,

Every day the jobless poor

Crowded to the Premier’s door

For he took of a nation’s store

And all the people they could tell

His bank-book to be furnished well,

At last this crook appointed a way

To quiet the poor without delay

He be bade ten thousand a ditch to dig

Whilst he washed down another swig

The bread line grew from day to day

And poor people’s savings dwindled away

The devil then began to pray

The parliament to without delay

Build a police force

The people by this time had heard

He planned to drive them as a herd

To concentration camps.

And from there a pigs sty, make, them work

For bread and swill

A concentration camp!

And when the nation these things hear

It goes further than the ear

Down, Down with Premier.

The people to the cities swarmed

Before—He’d been warned

The pigs had on him descended.

And ere that Premier’s corpse was cold

The nation in a bloody war was wrought

Down, came the order

And from this chaos what shall rise

O for what cause have young men died

In World war No. II

That this should happen to them

Who tried law and order to defend

Down with the grafters.

Down to the End

O trust you not in politics

In parties or in men

For each is but for profit

To betray you in the end

The love of gold, the love of gains

And of worldly pleasures

Shall in time their morals rust

And toss you to the devil.

My father’s concept of wrongdoing as leading the guilty party to punishment by the devil and his use of vocabulary such as “be bade” (a longer form of the word bade used in older versions of the Bible) show his familiarity with Christianity; however, while his high tone may indicate his youth, the poetry that followed in later decades continued to lament and rage against injustice. Indeed, his strong critical voice joined the voices of others as part of a long tradition of the social justice work of poetry (see Prendergast, 2012). Throughout his life my father was conscious of his poetic voice and continued to nurture it; in the 1960s, he typed some of his poems and included, in an altered form, the final two verses of the above 1945 work, noting the year of creation and his school grade. For him they were, perhaps, the “moral of the story”.

Escape/Displacement/Translation—Gisela

When the war broke out in Germany, my mother was a teenager without a father around. Before he left to fight, my grandfather had taught my mother how to navigate strong currents and escape dangerous whirlpools. Then, during the war and long after, he was gone, starving in a prisoner of war camp.

Thus, during the chaos of war and its aftermath, my mother was left largely to her own devices. She kept an ever present ear to the ground for sounds of danger. The notion of physical escape as the primary survival strategy became deeply ingrained.

Questions I Always Wanted to Ask My Mother

How did you swing it? After the war.

How did you break free, the train so full that no hand holds were left.

You had to belt yourself onto the last car, onto the railing,

that balcony off the end of the German caboose rumbling off and away,

that grey that I see in pictures.

There is no photo of this. You lean back,

the dark smoke, the wind, the wave of your hair, long then.

How did you do this?

The arch of your back. The iron of the last car leaving,

the track ahead,

the swell of your abdomen ripe with child.1

While Heather’s father dealt with injustice by developing his own personal language of rebellion and social commentary, my mother carved a path to safety through physical migration.

My parents left Germany after the war, my father first. Later my mother travelled over on a freighter with two young children: my older brother and sister. While the idea of emigration appealed to my mother’s love of adventure and physical challenge, the crossing was rough and the journey brought with it a profound sense of psychological dislocation. Her homeland, the country of her youth, lay in bombed-out ruins. Both her parents and two sisters had stayed behind. Two years later, when my mother’s youngest sister came over to visit, she died by drowning in a Canadian river. Like my mother, she had been taught to swim in strong currents, to be hyper-vigilant and to escape from danger. Like my mother, she survived the devastation of war. But unlike my mother, she did not survive the harsh new landscape. She was swept over a waterfall, broke her neck, and died.

My

childhood was filled with such tales-—tales of migration and

life-threatening crossings over water and land, the stories

themselves transported from another place. These dramas were meant to

entertain, but were always laced with unresolved trauma. When I

interviewed my mother near the end of her life, I asked, “Should

we speak German or English?” She chose English. She had

reinvented herself by learning to speak a new language in a new

world.

Going to Germany

It’s not only boats that cross water.

Travelling morse code messages

make a foreign sound:

tapping, dots and dashes

abstract on the page.

Going back with a new suitcase,

hard red.

Arriving with no key.

A father searches through his old collection

to find one that fits.

Leaving the motherland,

two toddlers tied together

with rope on the decks of the winter Atlantic

sick with loss and the tossing.

Then a father’s death.

Trying to return.

Papers invalid.

Crying before a man in uniform.

A sudden softening, the stamp of approval

and the movement towards something.

Now a son leaves home.

He must cross a huge new continent to go back,

first by train.

The holding at the station, the dark eyes,

the damp faces left behind.

Empty shoes with loose laces,

the unknown return.

The visit of a sister,

her death by water.

The gravestone sent over.

The search for remains.

Bodies lost

and at least two languages

once tied down to place.

The entry codes sometimes forgotten.

Numbers and buttons on a tiny key pad.

The overseas telephone voice gets fainter.

The receiver no longer holds the sound.2

When she first came to Canada in her early 20s, my mother had only schoolgirl English. Then in her 40s, despite family opposition, she started university and ultimately obtained her Masters in Literature and a Teaching Degree. Her English was masterful and in the end it seemed as if this was now her home language. Only her lingering accent still carried the loss and dislocation she felt.

I too have English as my working language. And from my mother, I have a love of literature and poetry. Unlike her, though, I have worked most of my professional life in the legal milieu using language in a different way to build a persuasive argument and defend against verbal attack. We both share a focus on safety as the primary concern.

Questioning Voice—Heather

Social, moral, and ethical concerns continued to occupy my father as he aged. In addition to volumes of poetry, philosophy, popular history, and science, his library included postwar paperbacks with graphic photos of the atrocities of the mid-twentieth century European concentration camps. After high school, the pressures of finding work, and later, the requirement to financially support his growing family, meant that my father did not get the opportunity to nurture his poetic aspirations at university. Still, he needed to express his voice; his concerns with social justice are evident in his poetry: From the 1950s through to his death in 1974 his poems focused on war; religious and social conformity, intolerance and hypocrisy; racial oppression; the meaning of life; and the inexorable fact of death. He sometimes noted when a poem was written in response to a media event and often recorded the exact minute it was put to paper. For most of that time, he worked for the British Columbia Telephone Company as a foreman. The job took our family first to a tiny isolated island community, next to a far-flung suburb of Vancouver, and finally to a northern town where, to my knowledge, there was little chance of sharing his poems with anyone. Nor, as far as I know, did he ever attempt to publish them.

My father died when I had just turned 17 and I received a legacy: a pile of paper—a disorganized collection of his writings. The majority of the poems and essays were penned with a ballpoint on used envelopes in his black spidery scrawl and showed little evidence of editing. They were hard to decipher. Other poems had been composed at his manual Remington typewriter. Many were critical of society, and therefore, to the young optimist that I was, seemed “dark.” For years I could not face them. For example, in the following poem (edited for length) he used the structure of the “Lord’s Prayer” as a scaffold to issue a condemnation of religious hypocrisy amongst churchgoers. I chose this one because the date shows that it was written on my birthday.

Nov. 14/64 11:30 p.m.

They dishonour the aged

They disown their youth

On earth, unto the end.

And in the mass say,

“Our Father who art in Heaven.’

They worship power

They bow to money

On earth, unto the end.

And in the mass say,

“Hallowed be Thy name.’

They refuse to feed the poor freely

They say let them work when there is none

On earth, unto the end.

And in the mass say,

‘Give us this day our daily bread’.

They threaten wars

They refer to peace as weakness

On earth, unto the end.

And in the mass say,

‘But deliver us from evil.’

They deny Thy power

They deny Thy glory

On earth, forever and ever.

And in the mass say,

‘For Thine is the power and glory forever and ever.’

They seek their own ends

They seek their own destiny

On earth, unto its end.

And in the mass we say,

‘Amen.’

By using the word “we” in the final verse my father also implicated himself as a hypocrite. At this time, he was struggling with his intellectual and moral commitment to the United Church of Canada.

New Understandings: Teaching

Heather

Such work involves remembering details about my father and my sustained attention means that I create new understandings. I am now older than he was at his death and realize that his writings are those of a relative youth—he only survived to young middle age. Also, despite his belief in the value of education, strongly enunciated to us when we were young, I now recall he had not had a very solid education himself. My appreciation of his work has grown and I am intrigued by his practice of using poetry to chart and reflect on his experience (see Soutar-Hynes, 2012).

Window

Time magazine asks “Is God dead?”

And, Dad, you wonder.

Digesting

The United Church Observer,

Buber’s philosophy,

Modern European Poetry,

The Screwtape Letters.

A workingman, writing a ‘window’

early death.

Decades pass, your tattered poems mute

scrawled on

graph paper, foolscap, manila,

Safeway and Super Value writing tablets,

used envelopes, Travel Lodge notepaper,

orange Daily Colonist stop delivery notices,

a Miracle Sandwich Spread box top.

Your window, my gift,

my professorship, your dream.

My concern has been to rescue fragments of my father’s story in an attempt to amplify his voice and this work has offered much to my teaching. Examining the origins of my professional voice led me to wonder how the voice I use in the classroom influences my students. By employing a detached voice perhaps, I imply that this particular form of narrative has high value. Through modelling personal inquiry through poetry, I am able to encourage my students to engage in their own processes of inquiry and thereby support the growth and expression of their voices, which is so important to learning. Further, by exploring my own history and practices, I am more able to hear marginalized voices (Bride, cited in McLeod, 2011), while my telling of personal stories may help students relate to each other. Through making my narrative choices conscious, I have created a safer space in which others feel invited to play, and finally, by cultivating the images in my personal stories, I pave the way for more finely drawn narratives to emerge and be heard, for both my students and myself.

Gisela

My mother’s leadership style was embodied from the start. We see this in the poem, Schumi’s Turn, and it never changed. Perhaps as a young adult I filled the gap in my mother’s narrative by abandoning my childhood voice and adopting the disembodied, analytical, and at times aggressive voice of the lawyer and social activist. In some ways, this was an early attempt to find my place alongside the dominant voice within my family of origin and to avoid being locked into a subordinate pre-scripted position. But as a poet, I am also attentive to the more elliptical voice, the subtle voice, the voice that emerges in the spaces created by silence and personal reflection. H. L. Goodall Jr. (2005) speaks of a narrative inheritance within families and how the incomplete narratives of our parents are often given to us to fulfill. For me, this is the story teller, the more inward looking reflective part of my mother that she had to suppress in order to survive. I now ask: If my mother had grown up in peacetime what kind of leader would she have become? Would she have had the space, the safety, to let her fragments, her vignettes, evolve into something more robust? As a poet and social activist, I can now pick up at least some of the abandoned threads of her life narrative and ask how these relate to my own trajectory. In working with the images left to me by my mother, I have learned more about how she told a story—the cryptic action elements she focussed on, the absence of an analytical framing device, the lack of political context. As a child, I received these images in the spirit they were given: This is just what happened; we survived and these events seemed normal to us.

Throughout this process, I ask, Where does the voice of the child come from? I see it has deep roots in one’s early context: in books, music, community, and church, as well as in the conversations of parents and their friends and in the languages they choose to speak, things that are said and things that are only implied, nestled within an image or within the body. This is the intellectual and artistic context that the family provides.

Lineage

After Patrick Lane’s Poem “Family”

My father is an axe swung high overhead,

his steel edge

just catches that glint of sun out back.

His blade whistles down through space,

his handle gripped by some unseen executioner.

My mother is a pair of walking boots

grabbed and put on two feet, quick

when the soldiers come to the house,

just before the long forced march

into winter.

Now, no one is home.

I am the gate to the garden.

My latch is unlocked, my hinges creak

open shut, open shut

with the force of an oncoming storm.

Having

a voice that is listened to and recognized in the professional milieu

is a privilege, whether one works as a teacher, a lawyer, or a

writer. By engaging in poetic inquiry, I have learned how the

development and ethical use of my own voice is influenced by my

ability to hear, to listen more deeply, more acutely, for suggestions

and implications that may underlie the voices of others. I now listen

for the undertones, sometimes contained in unformed or fragmented,

and possibly, wounded voices. Partly through hearing my mother’s

voice, I have learned to listen for and embrace sensations and

emotions as part of the narrative, and to weave these elements into

my retelling. From her I have learned that sometimes too much

analysis gets in the way. The development of my listening ear is not

something I can assume; it must be practiced and honed through a

process of writing as open inquiry with no preconceived outcome in

mind. This can be achieved through the craft of poetry.

Through this work, I am also reminded how I can use my voice in different ways, and that this is in itself a political statement, an aesthetic positioning. In the more traditional lawyer’s role, I might use the professional stage I have to demonstrate my perceived oral virtuosity and “win over” others through the use of tightly constructed arguments. This is using the authoritative voice as a kind of power play. However, with practice, the more poetic voice can create space and an emotional context for others, encouraging their voices to form part of the dialogue, the meaning making. This process of facilitating collective inquiry is something I continue to use in my writing and in my social justice work, training police, prosecutors, and those who advocate on behalf of women and children who are victims of crime.

Epistemology, Writing, and Research

The two of us have always shared rich verbal dialogues and now it has expanded into written form. Having met when we were both students of history at the University of British Columbia, we wonder if the structure of our dialogue reflects this orientation from our impressionable undergrad years? There seems to be a kind of shorthand or common base or foundation that allows us to build ideas together quickly even though we have been operating with different discourses in recent years: Heather in Education and Gisela in Law. Perhaps this harkens back to an earlier time in our intellectual development and touches a deeper layer or vein? We learned to view the writing of history as rooted within the humanities. As researchers, we could be engaged and passionate; we did not have to perform as “objective” observers. We questioned the possibility of a truly “dispassionate” voice.

Further, we understood that language is not separate from the theme or area being studied and is not to be ignored. Language is itself part of the analysis and the positioning of the work. Our experience is that the writing process is a form of inquiry (Richardson & St. Pierre, 2008). As we change the wording and framing of our piece in response to further dialogue, different themes emerge or rise up. For Gisela, hypervigilance and escape are significant themes in her mother’s narrative. While this was present to some extent as an image in the Lineage poem (putting on the boots when soldiers come), Gisela had not articulated it consciously until much later through a process of discussion with Heather, and through revising and refining this article, which includes a prose analysis portion.

We are reminded that poems carry within them coded information not readily available to the logical brain engaged in purely analytical writing. The poetic realm is a place where ideas emerge sooner and in a denser, more enigmatic form. The poem is a container that can later be unpacked both through analysis and through working with the image.

Though Gisela wrote her poems in a private setting, the subject matter, imagery, and themes were influenced by the process of dialogue with Heather while on long walks together in the forests and neighbourhoods of Victoria. We both let the conversation take its own course and had faith that the important themes emerging in our walks would naturally find their way into the work, rather than transcribing them, possibly limiting them their flow at the time. Schumi’s Turn, a poem about Ursula’s school years, was not planned but emerged organically from discussions and readings regarding the role of the teacher and Donald’s experiences moving from a rural one-room schoolhouse to an urban school.

Oral presentation also infuses our writing. Because meaning is made jointly, the part played by the audience is important, too.

Gisela considered, “How would the poems work with the framing device of the prose part of the article?” She asked questions such as: Do I write the poem differently because of its positioning in a larger prose piece which includes analysis of content? Will the poems still stand on their own? Do they need to? To what extent are the poems part and parcel of the larger article? Would it even be appropriate to separate them out from the larger piece? Or rather, in contrast, perhaps the piece that is created through the process of poetic inquiry and duoethnography is its own distinct form made up of a combination of poetry and prose.

In his discussion of poetic inquiry Brady (2009) notes, “Poetic processes can be used both as tools of discovery and a unique mode of reporting research” (p. 14). Indeed, the poignancy of the final lines of Gisela’s poem “Going to Germany” served as a tool of discovery for Heather. Reading, “The overseas telephone voice gets fainter. The receiver no longer holds the sound” evoked her own experience—the crackling, long distance phone connection and the awkward hesitancies of her last conversation with her father. Further Window, Heather’s poem for her father, can be understood, as Brady suggests, as a report of research resulting from our dialogue as co-researchers and through her dialogue with her father’s poems as personal and cultural artefacts (Sawyer & Norris, 2013). By creating a poem of response, Heather strengthens her own voice in the world.

References

Boughn, M. (2013). The new American poetry revisited—again. Retrieved from www. dooneyscafe. com/archives/3761

Brady, I. (2009). Forward. In M. Prendergast, C. Leggo, & P. Sameshima (Eds.), Poetic inquiry: Vibrant voices in the social sciences (pp. 12-17). Boston, MA: Sense Publishers.

Butler-Kisber, L. (2012). Poetic inquiry. In S. Thomas, A. Cole, & S. Stewart (Eds. ), The art of poetic inquiry (pp. 142-176). Halifax, NS: Backalong Books.

Goodall, H.L., Jr. (2005). Narrative inheritance: A nuclear family with toxic secrets. Qualitative Inquiry, 11(4), 492-513. doi: 10.1177/1077800405276769

Leggo, C. (2010). Writing a life: Representation in language and image. Transnational Curriculum Inquiry, 7(2), 47-61. Retrieved from: http://nitinat. library. ubc. ca/ojs/index. php/tci

McLeod, H. (2011). "House very strong”: Six families, one house, and the life of an arts-based research project. In C. McLean & R. Kelly (Eds.), Creative arts in research for community and cultural change (pp. 255-274). Calgary, AB: Detsilig.

Pelias, R. J. (2008). H. L. Goodall’s A need to know and the stories we tell urselves. Qualitative Inquiry, 14(7), 1309-1313. doi: 10.1177/1077800408322680

Prendergast, M. (2009). Introduction: The phenomena of poetry in research. In C. Leggo & P. Sameshima (Eds.), Poetic inquiry: Vibrant voices in the social sciences (pp. xix-xiii). Boston, MA: Sense Publishers.

Prendergast, M. (2012). Poetic inquiry and the social poet. In S. Thomas, A. Cole, & S. Stewart (Eds. ), The art of poetic inquiry (pp. 488-502). Halifax, NS: Backalong Books.

Richardson, L., & St. Pierre, E. A. (2008). Writing: A method of inquiry. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Collecting and interpreting qualitative materials (3rd ed., pp. 959-978). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Ruebsaat, G. (2009a). Superwoman. Island Writer Magazine, 7(1), 12.

Ruebsaat, G. (2009b). Constellation. Island Writer Magazine, 7(1), 35-38.

Ruebsaat, G. (2013a). Going to Germany. In J. Huebert (Ed. ). Pathways not posted. (3rd ed., p. 9). Victoria, BC: Quadra Books.

Ruebsaat, G. (2013b). Questions I always wanted to ask my mother. In P. Lane (Ed.), In that wild place (p. 14). Lantzville, BC: Leaf Press.

Said, E. (1993). Culture and imperialism. New York, NY: Alfred. A. Knopf.

Sawyer, R., & Norris, J. (2013). Duoethnography: Understanding qualitative research. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Stewart, S. (2010). The grief beneath your mothertongue: Listening through poetic inquiry. Learning Landscapes: Poetry and Education: Possibilities and Practices, 4(1), 85-104.

Soutar-Hynes, M. (2012). Points of articulation: A letting go and a reaching towards—a poet’s journey. In S. Thomas, A. Cole, & S. Stewart (Eds.), The art of poetic inquiry (pp. 427-445). Halifax, NS: Backalong Books.

Struthers, J. (1983). No fault of their own: Unemployment and the Canadian welfare state 1914-1941. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Wiebe, S., & Snowber, C. (2012). En/lived vulnere: A poetic of impossible pedagogies. In S. Thomas, A. Cole, & S. Stewart (Eds.), The art of poetic inquiry (pp. 446-461). Halifax, NS: Backalong Books.

Endnotes

——————

1 “Questions I always wanted to ask my mother” first appears in 2013 in P. Lane (Ed.), In that wild place (p. 14), Lantzville, BC: Leaf Press.

2 A different version of “Going to Germany” first appears in 2013 in J. Huebert (Ed.), Pathways not posted (p. 9, 3rd ed.). Victoria, BC: Quadra Books.