Liminal

Lives: Navigating the Spaces Between (Poet and Scholar)

C.

L. Clarke

University

of Saskatchewan

This

paper takes up the question of what it means to inquire into our own

narrative or autobiographical beginnings within a narrative inquiry.

Specifically, I inquire into the use of poetic representation and

poetic expression to explore the layers of autobiographical

beginnings that inform the researcher’s life as both a scholar

and a poet. While autobiographical beginnings are only one aspect of

narrative inquiry, they constitute an essential component to

understanding our own place as researchers within a narrative

inquiry. In this paper, I examine the importance of narrative

beginnings or autobiographical beginnings to narrative inquiry.

Through the demonstration of autobiographical beginnings expressed

poetically, I argue that an examination of narrative beginnings is

essential to positioning the researcher within the research. During

the inquiry, the researcher, like the participants, is in a state of

becoming. Autobiographical beginnings bring to the surface those

factors influencing the researcher’s perspectives, thus

locating the researcher within the inquiry as well as within a larger

life context. In addition to this primary focus of locating the

researcher within the research through narrative beginnings, I

demonstrate the efficacy of employing poetic representation and

poetic expression within a narrative inquiry. Both

narrative/autobiographical beginnings and the poetic representation

of autobiographical beginnings highlight the liminal nature of the

researcher’s identity within an inquiry. My choice of poetic

representation of autobiographical beginnings is not incidental or

merely aesthetic. Poetic representation of autobiographical

beginnings within a narrative inquiry is a rigorous and effective

means of articulating the researcher’s location while, at the

same time, recognizing how the shifting nature of identity requires a

revisiting of the researcher’s perspective to remain connected

to the ways in which the narrative inquiry continuously reshapes the

researcher’s understandings. In narrative inquiry, this process

unfolds over the course of an inquiry through the telling, retelling,

and reliving of the narratives. Through the poetry shared in this

paper as well as the unpacking of the poetry, I demonstrate a small

piece of that cycle. The poetic representation already exists as a

retelling of some of my own pivotal experiences, especially pertinent

to a larger inquiry underway, examining the life and learning that

occurs on the edges of community, spaces conventionally constructed

as marginalized. My research is situated in my understanding of my

experience. As part of a larger narrative inquiry, it attends to the

conventions of narrative inquiry as a methodology (Clandinin &

Caine, 2013; Clandinin & Connelly, 2000; Caine, Estefan, &

Clandinin, 2013) while employing poetic representation to express key

moments in the researcher’s experience. In my focus on

retelling through poetry and the narrative unpacking of that poetry,

I engage in a reliving of those experiences, as does the reader. I

retell, and thus, relive my own experiences of exclusion, isolation,

and perceived marginalization. Through this retelling and reliving of

my own experiences related to life and learning on the edges of

community, I demonstrate the essential nature of autobiographical

beginnings to the deeper understanding of my research wondering about

those spaces constructed as marginalized.

Autobiographical

Narrative Beginnings: Beginning With Who I Am

Every

day begins for me with writing. I read from the works of other

writers and when some piece of what they have written resonates with

me, I respond in my own writing to those ideas. Always, my writing

returns to my life, to the specific, concrete details that make up my

life, to the moments of wonder, the questions, the veiled answers

that emerge through all this writing and thinking that comprise my

intellectual life. Often, my wondering spirals down into the past, to

the origins of my ideas that grew out of a particular moment or in a

particular place. With each recollection, I am remade through the

retelling of these moments in reflection, the rewriting of my own

history repeatedly. Inevitably, these processes of reflection and

recollection lead to poems. In the distillation of language into

poetry, I find my truest expression of self and thought. This is who

I am. Through poetry I relive the narratives of my life, and through

that reliving I become who I am. Ontologically, this process is the

basis for my identity as a poet. From a theoretical and

methodological perspective, I recognize this process as a cycle of

meaning making grounded in the tradition of narrative inquiry. At the

same time, I employ poetic expression and poetic representation of my

autobiographical beginnings in order to attend to my identity as both

a scholar and a poet. In the liminal space between my identity as

poet and my identity as scholar, I am able to inquire into ways in

which these identities might converge to create richer opportunities

for meaning making in my research.

Clandinin

and Caine (2013) use the terms autobiographical or narrative

beginnings to refer to the personal stories narrative inquirers

explore to “make evident the social and political contexts that

shaped our understandings” (p. 171). Clandinin and Connelly

(2000) assert, “One of the starting points for narrative

inquiry is the researcher’s own narrative of experience, the

researcher’s autobiography” (p. 70). Clandinin and

Connelly (2000) also say, “narrative beginnings of our own

livings, telling, retellings, and reliving help us deal with

questions of who we are in the field and who we are in the texts that

we write on our experience of the field experience” (p. 70). In

other words, inquiring into our own narrative beginnings is essential

to any research endeavor. Examining our own stories along with the

stories of our research participants is essential to understanding

the identity-making process. Because I am a narrative inquirer, I

attend to my autobiographical beginnings in order to understand

myself better as I enter into research alongside my participants. At

the same time, I recognize a strong sense of self that identifies as

a poet and requires poetic expression as part of those narrative

autobiographical beginnings. Leggo (2010) states, “For stories

to be creatively effective, they need to be shaped generatively and

generously” (p. 68). He recognizes the need to attend to the

multiple facets of our identities as researchers when he asserts, “We

need spaces for many kinds of research, including lifewriting

research that focuses on narrative, autobiographical, fictional, and

poetic knowing” (Leggo, 2010, p. 68). As Leggo suggests, my

autobiographical beginnings are both narrative and poetic. I examine

the space between my identity as scholar and my identity as poet by

sharing four original poems describing key experiences in my own life

that shaped my identity and continue to resonate through my research

wonders.

In

the Middle of the Muskeg: Locating Myself Within the Inquiry

Muskeg

I

listened in the night

through

the fog of dreams

to

the world asleep

and

not asleep

around

me.

In

the back gabled bedroom

one

narrow window looked out

over

the garage, dark paneling

the

smell of moth balls

always

cold floors.

The

wire-springed bed frame

with

the metal headboard

creaked

when I breathed

and

all I could do was breathe

and

breathe

into

the night

as

I listened,

scurrying

in the walls

relief

when grey light

touched

the edges of the window

long

before sunlight burned

past

the fire-blackened pine

and

miles of Muskeg

behind

the store.

A

bulldozer once broke through the loam, Dad said

and

sank until it was lost.

He

said, No one knows how deep

the

Muskeg is—so deep

it

might go on forever.

We

clung to a strip of gravel,

an

atoll in a sea of Muskeg.

You

couldn’t go anywhere.

There

was nowhere to go—

our

lives defined

by

the gravel pad

that

kept us all from sinking

out

of sight.

These

days I don’t travel far from home.

I

stay inside this room,

wonder

if the rest of the world exists

or

if I lie awake still afraid

surrounded

by miles of Muskeg. (Clarke, personal writing, 2013)

In

this poem, I express the sense of isolation and disconnection that

permeated my life growing up in Northern Saskatchewan. The poem

Muskeg is

concretely situated in a place that actually existed. In the early

seventies, the highway to La Ronge in Northern Saskatchewan was the

only highway leading in and out of the North. When we first moved

there, the road itself was unpaved. My parents’ store perched

on a gravel-reinforced

lot at the junction of Highway #2 and #969, leading to Montreal Lake.

On either side of the highway, except for the gravel pad where we

lived, muskeg stretched for miles in every direction, creating both a

geographical and metaphorical barrier to movement.

Clandinin

and Caine (2013) say “Place directs attention to places where

lives were lived as well as to the places where inquiry events occur”

(p. 167). Of all the places that I have lived in my life, why do my

recollections constantly return to Timber Cove and life on the edge

of the muskeg? The persistence of these memories indicates that the

experiences lived out on the edge of the muskeg hold deeply rooted

connections to the research wonders I carry with me today.

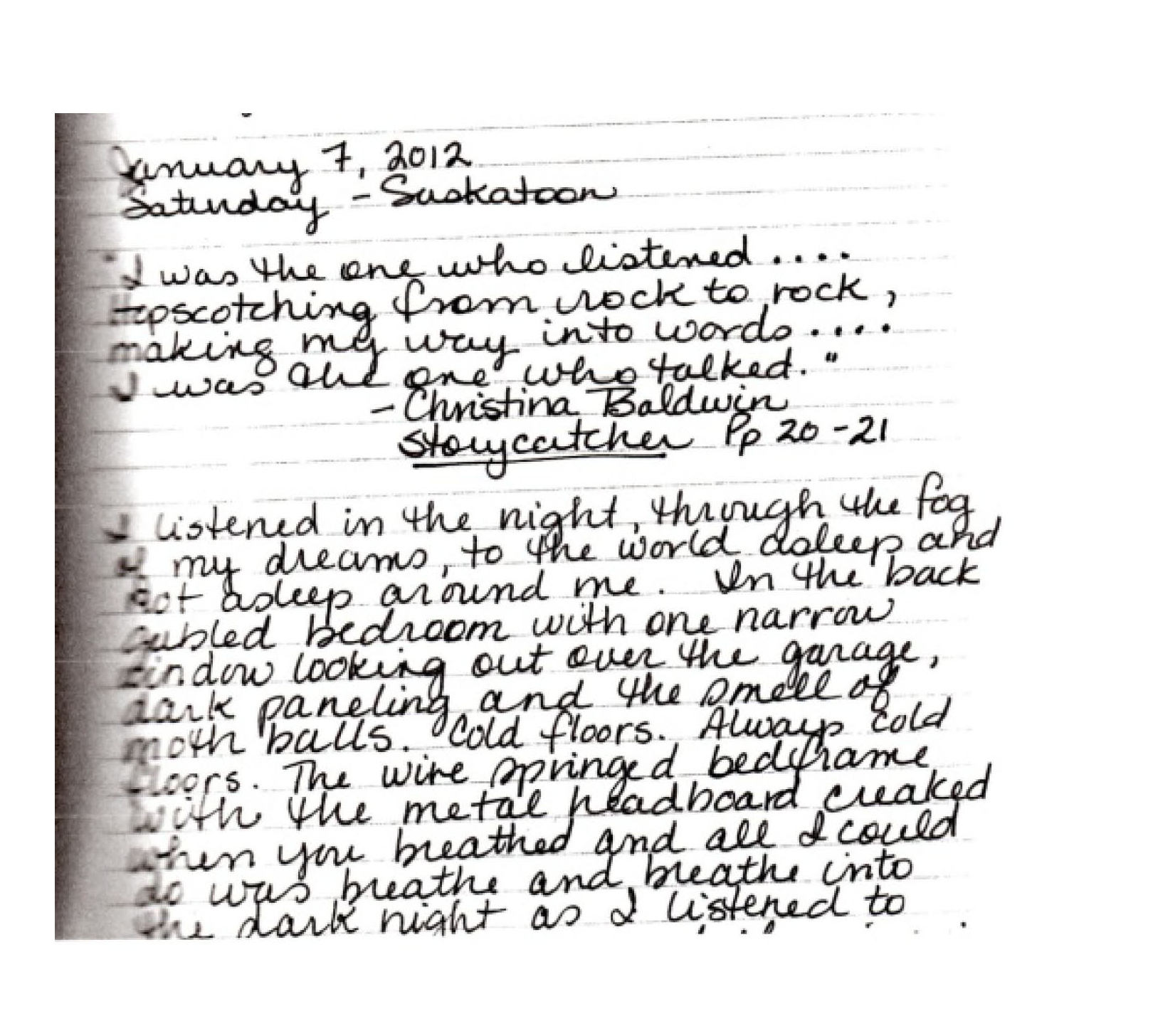

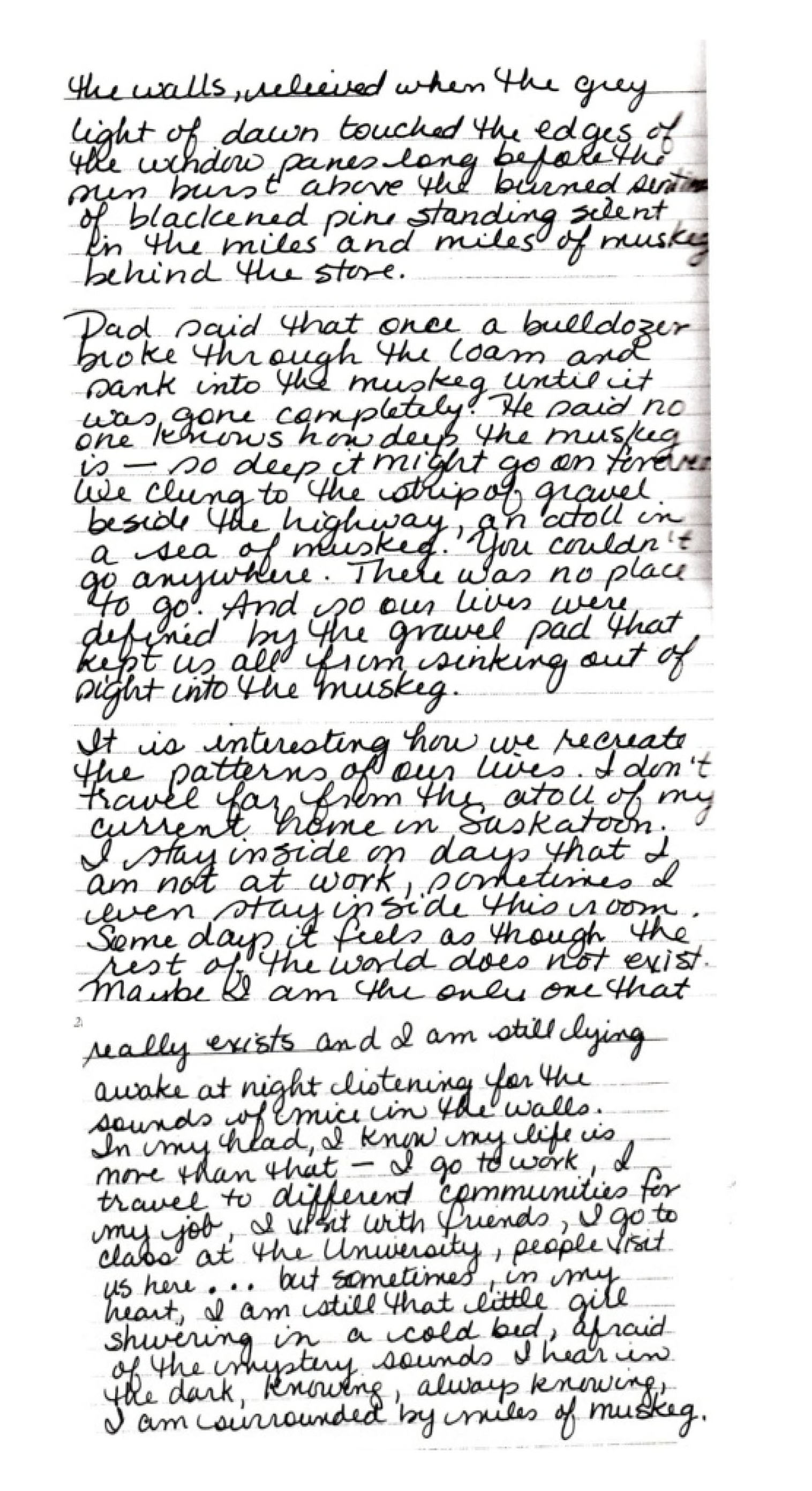

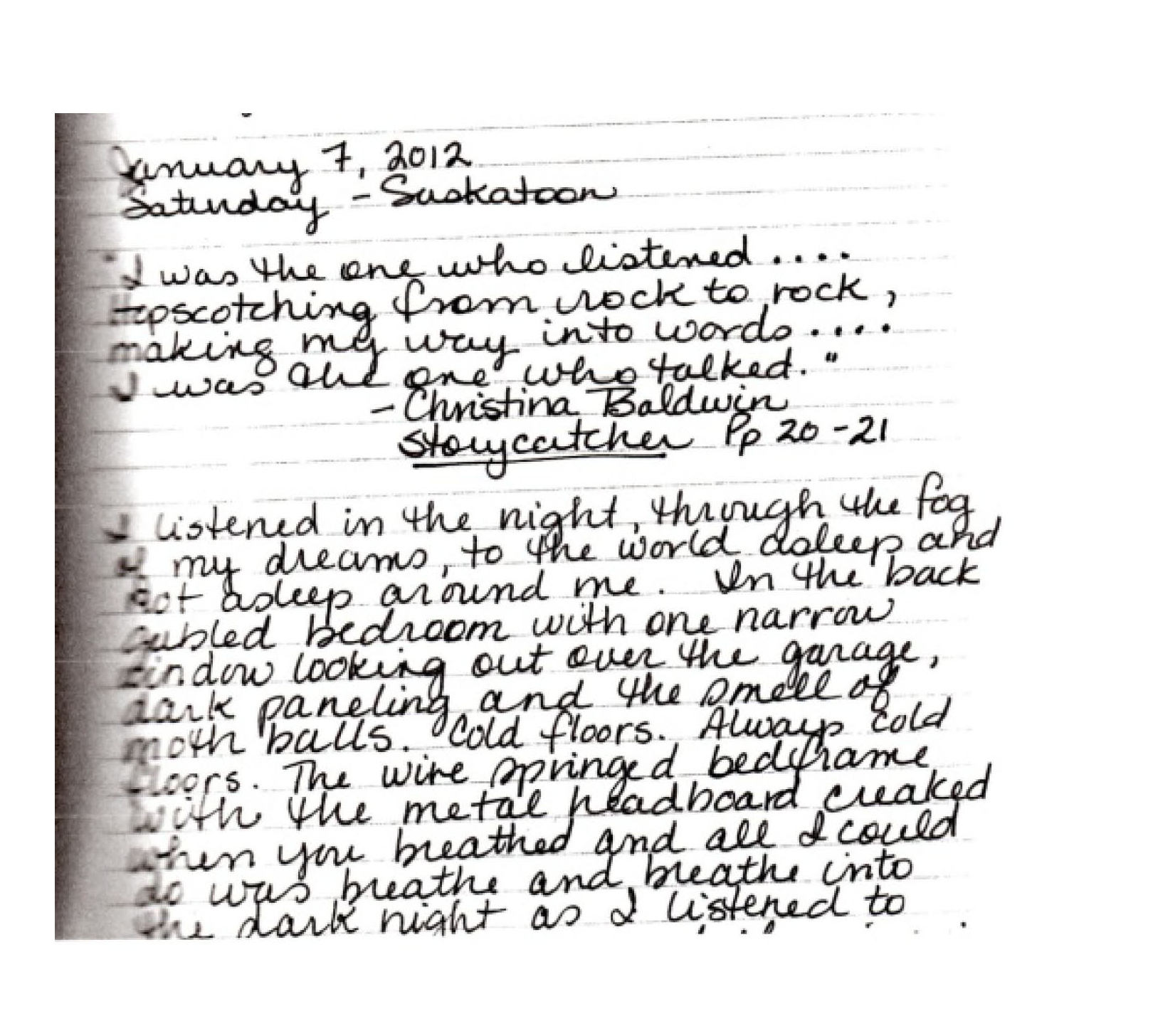

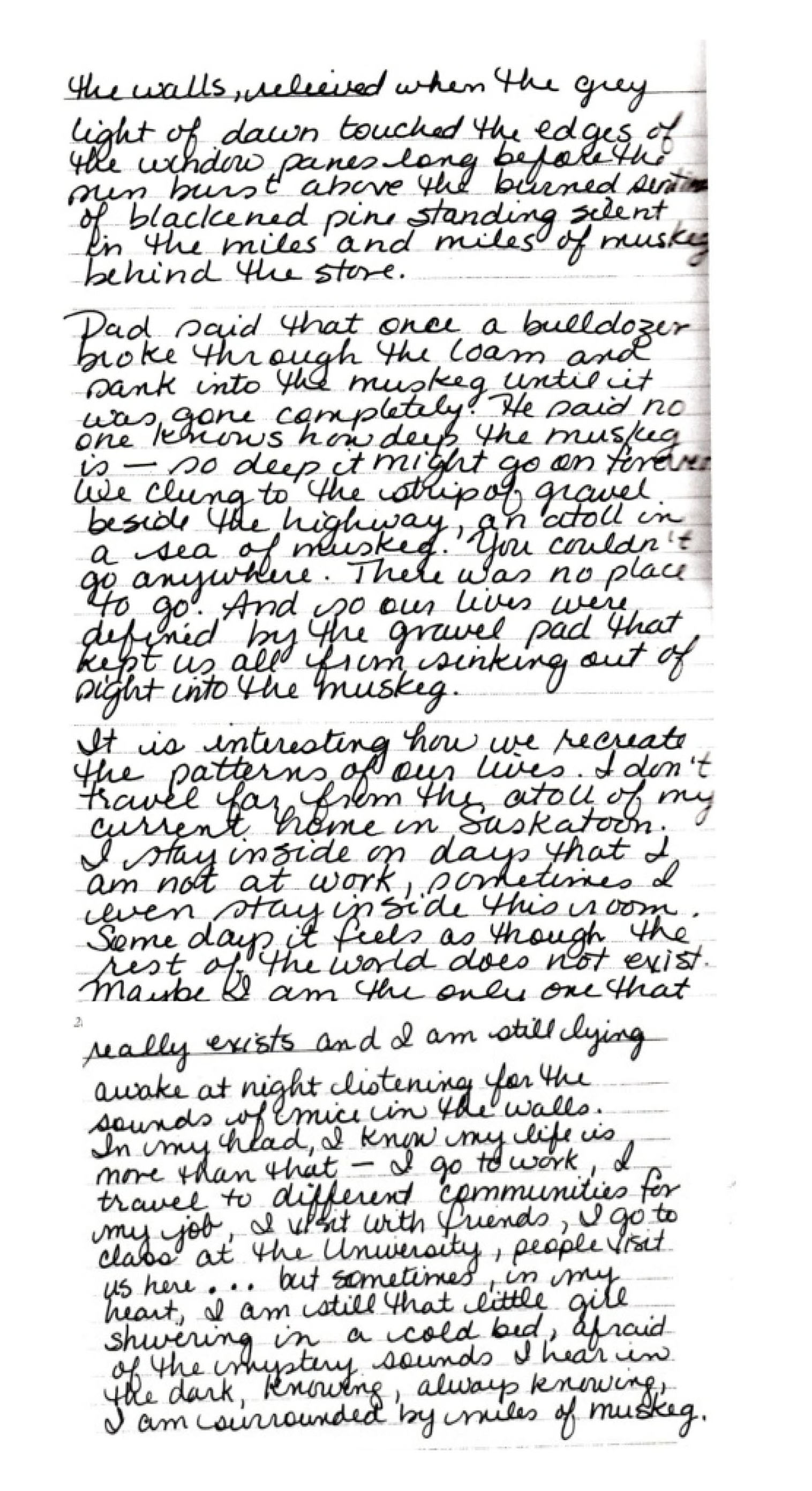

I

first began to explore the themes of the poem Muskeg in

January 2012, thinking about what part of my own life created an

interest to understand the experience of marginalization. In my

journal writing, I reached back to a place where a sense of isolation

and marginalization were most acute. I wrote about my experiences

growing up in Northern Saskatchewan as someone transplanted into that

landscape—a landscape that was, to me, foreign. In retrospect,

however, I realize that the landscape was not foreign, but rather I

was foreign to the landscape. The poem, however, is a deeper

expression of the recollection of being foreign to one’s

surroundings. Muskeg, in its temporal movement between the

past and the present, connects the experiences of the poet as a child

to the experiences of the poet as an adult—to the experiences

of the poet as a researcher. Methodologically, the poetic

representation of those recollections reaches deeper than the

recollections explicated in the journal entries. The poetic form more

richly captures the complexity of those experiences that acted to

shape my identity as a poet and that continue to shape my identity as

a researcher.

I

first began to explore the themes of the poem Muskeg in

January 2012, thinking about what part of my own life created an

interest to understand the experience of marginalization. In my

journal writing, I reached back to a place where a sense of isolation

and marginalization were most acute. I wrote about my experiences

growing up in Northern Saskatchewan as someone transplanted into that

landscape—a landscape that was, to me, foreign. In retrospect,

however, I realize that the landscape was not foreign, but rather I

was foreign to the landscape. The poem, however, is a deeper

expression of the recollection of being foreign to one’s

surroundings. Muskeg, in its temporal movement between the

past and the present, connects the experiences of the poet as a child

to the experiences of the poet as an adult—to the experiences

of the poet as a researcher. Methodologically, the poetic

representation of those recollections reaches deeper than the

recollections explicated in the journal entries. The poetic form more

richly captures the complexity of those experiences that acted to

shape my identity as a poet and that continue to shape my identity as

a researcher.

Clandinin

and Connelly (1992), drawing on the work of Schon (1979), assert,

“metaphors are no mere ‘anomalies of language’ but

are instead expressions of living” (Clandinin & Connelly,

1992, p. 369). Clandinin and Connelly (1992) further assert the

importance of metaphor in understanding teacher narratives, stating,

“We and other teachers are, in an important sense, living our

images and metaphors” (p.369). To understand Muskeg

as illustrative of a moment in my “story to live by”

(Connelly & Clandinin, 1999),1

it is necessary to understand the metaphor of the muskeg that

permeates this poem.

Muskeg

is the Cree word for bog.

The muskeg in the poem was a dangerous place because you could break

through the thin layers of mossy soil and drown in the water below.

In this way, the muskeg defined the place where I grew up as a

negative space surrounding the small gravel island built up beside

the highway that was solid enough to support the store with its

living quarters upstairs. Furthermore, the muskeg in the poem

represents the limitations that grow out of the fear of the unknown.

The landscape described in the poem identifies the sense of

limitation the poet as a young girl experienced while living so far

away from anyone else. As a child, I remember the familial travelling

in and out of communities that my parents identified as more valuable

in relation to our home place on the gravel pad. Always, the muskeg

was a benchmark for our lives in relation to other communities. As an

adult, I recognize that Muskeg

has become a benchmark for my research and autobiographical

wonderings. When I was growing up beside the muskeg, we moved through

the borders of inclusiveness and exclusiveness, our identities

shifting as we travelled through each day and through each landscape.

This movement through the borders of communities that I never seemed

to belong to regardless of their make-up

has created in me a persistent desire to understand more deeply the

experience of being on the edges of community.

As

I consider the experiences detailed in the poem Muskeg, I

realize that this poem also recognizes the impact of the stories that

parents tell to keep their children grounded to the same place,

stories that limit their sense of agency and mobility, stories that

work to keep them safe. The story of the bulldozer sinking into the

muskeg was a cautionary tale told by my father to keep my siblings

and me out of the muskeg, to keep us safe from harm. It accomplished

more than that, though—for the longest time, it defined what

was possible and what was not possible.

A

landscape of limitation, defined by borders of fear, of isolation,

and of the unknown, shaped my understanding of experience as also

defined by limitation and marginalization. This definition of the

landscape grew out of my experience as someone transplanted into the

landscape instead of being a part of it. Furthermore, in my adult

contemplations of the historical significance of our arrival and

lives on the gravel atoll beside the muskeg, I recognize that we were

settlers in the muskeg and lived with the settlers’ mentality

of mixing only with other settlers, not with those indigenous to the

area. Perhaps our lives might have been less permeated by a sense of

isolation and disconnection if we had allowed ourselves the community

of the people indigenous to the area. Perhaps they might have taught

us to view the landscape as less harsh or inhospitable if we had been

open to cultivating community with those for whom the landscape was

home.

Not

long ago I had the opportunity to share my musings on the Muskeg

with a group of colleagues during a research retreat. In an

astounding moment of serendipity, one of the research retreat

participants shared that he, too, came from the area my poem

describes. As we talked about the importance of this place to the

development of my identity, this person shared a very different and

much more positive experience of the muskeg. This sparked in me a

wondering around whether or not and how our experiences of inclusion

and exclusion might be, at least in part, a matter of perspective.

What if that perspective provided an opportunity to shift? How might

such a shift in perspective influence the identity making growing out

of that experience of place?

My

poem Muskeg

describes not only a distinct location but also the passage of time

and how the experiences of childhood reverberate through our adult

selves. Furthermore, it clearly articulates the sense of isolation

present in the researcher-poet’s

life—the feeling that the ability to interact socially was

somehow impaired by a childhood spent living in isolation. These

feelings and memories are integral to identity making, particularly

my identities as researcher and poet. As someone who has lived in a

space defined primarily by limitations, I am aware of the ways in

which we limit others’ experiences not only to define them but

also to confine them within expectations. It is this understanding of

my autobiographical beginnings as a researcher-poet,

experienced through the writing and retelling of my poems, which

heightens my interest in learning more about the ways in which life

on the edges of community unfolds for others.

Life

on the Edges: Navigating the Changing Landscape of Autobiographical

Beginnings

The

Blue Dress

I

remember the details

preserved

like dried beans in a mason jar

one

hundred and forty-five dollars a month

for

the bachelor suite at Nesbit Apartments

half

of what I made a month in my job

working

the desk at the YWCA –

one

room no bigger than a bedroom

kitchen

in a closet and a bathroom

with

a claw-foot tub

circa

1912 hardwood

three

tall windows

facing

West.

In

the way back

before

language

every

thought is an image

sealed

in cellophane.

I

am visiting my dad’s mom

in

an apartment with the same floors.

She

wears a blue dress and sips Red Rose tea

beside

the same three windows.

Something

in her frown

and

concrete chin

frightens

me

so

I never wear a blue dress –

only

blue jeans and loose peasant blouses.

My

bed is under the windows

to

catch the scraps of breeze

lifting

from burning asphalt –

downtown

Prince Albert in the summer,

as

big to me then as Los Angeles

or

New York; big enough

to

hide from change

two

floors above

the

street. (Clarke, personal writing, 2013)

The

Blue Dress is a poem that, like Muskeg,

captures the experience of living on the edges of community. It

describes my memories and my living situation as a young woman who

feared she would become like her grandmother whose life had always

seemed confined within her small apartment with little prospect for

interaction outside. Like Muskeg,

this poem relies heavily on a sense of place and provides concrete

images of the details that define that space. Less concrete, however,

is the developing identity revealed within the poems, often through

the juxtaposition of images rather than the explicit detailing of

cause and effect. Here we see a grandmother through the eyes of a

very young child whose impression is that she is rigid, unmoving, and

ultimately unhappy. The child draws a connection between her

grandmother`s sternness to the place where her grandmother lives as

well as what she wears. Within the poem, however, a temporal shift

occurs in which the past reaches forward to claim the present. The

child, now grown, finds herself in the same or a similar apartment as

the one that her grandmother lived in and despite the young woman’s

ritual act of never wearing a blue dress, she struggles to live a

different story from her grandmother`s story. There is also a sense

of unfolding awareness in the poem as the speaker realizes life in

the apartment is both similar to and different from her grandmother’s

life. This sense of the familiar within the unfamiliar creates a

moment in the woman’s life where she is stuck in place—unable

to enact change and move forward and unable to accept the life she is

living.

As

with the poem Muskeg,

the apartment described in the poem is an actual place that I lived

in when I was twenty-two. The descriptions in the poem of my

apartment are as accurate as memory allows, not fictionalized nor, as

far as I can recall, exaggerated. I also distinctly remember visiting

my grandmother in a similar apartment when I was very young. Her

apartment certainly was located within the same downtown

neighbourhood. It may even have been within the same building,

although that is somewhat unclear to me at this point. What is clear,

however, are the emotions that persistently cling to the memory and

the remembered determination to avoid my grandmother’s solitary

lifestyle. Grandma lived alone in that little apartment and I lived

alone in my similar little apartment. It seemed to me then that my

life was replicating the experiences I thought my grandmother had

experienced. I viewed that as negative and in danger of defining who

I would become in later adulthood. I cannot say specifically why this

was so concerning to me. I recall that it was tied to the employment

I had as the night receptionist at the YWCA, which provided only

enough money to live on and not enough to change my life

circumstances. My income certainly would have categorized me within

the group of the working poor, but as a young woman this was an

accepted income bracket. All of my friends who were not living at

home were living in similar tiny apartments and reveling in their

freedom. I was not reveling. I was wondering how I would keep myself

from being trapped within that socioeconomic space and place forever.

In The Blue Dress,

both the child and her adult self demonstrate a complex mix of desire

for change and fear of change. It is a position that the young woman

in the poem experiences, that I experienced—a position that the

woman must adopt due to circumstances—and it is a positioning,

a space and place that the young woman chooses to remain in.

Socioeconomic

status is one of the ways in which we define ourselves or can be

defined by others. Terms such as poor, middle class, and affluent all

serve descriptive purposes in relation to some more or less

articulated norm. While it can be argued that these methods of

defining people or groups of people are inherently constructions with

no connection to the actual experiences and life circumstances of

people, there can be no doubt that these overarching categories do

have an influence on the ways in which people define themselves.

These definitions, however close or far from reality they might be,

are part of a landscape of identity making that emerges out of the

experiences of people. In The Blue

Dress, my younger self recognizes the

starkness of her grandmother’s apartment and connects it to her

grandmother’s identity as harsh and rigid. Rightly or wrongly,

my younger self creates a causal relationship between the space/place

and the identity of her grandmother. When she finds herself living in

a strikingly similar space, she struggles to ensure that her identity

development does not become indelibly influenced by the space.

In

contemplating the themes and metaphors of The

Blue Dress and Muskeg,

I begin to wonder what part of our experiences might be externally

generated and what parts might be internally endured or accepted? At

what point do we begin to story ourselves in the ways that we are

storied? Is it possible to mark the transition or, concomitantly, to

resist the transition? Do people living and learning on the edges of

community inevitably come to see themselves as marginalized?

We

experience The Blue Dress as a retelling. The speaker in the

poem is looking back from some future that has escaped the apartment

with the three windows facing west, just as the speaker in Muskeg

escaped the gravel atoll. However, these escapes are not the foci of

the poems. They are incidental, inferred, with the primary focus

being on those experiences of isolation and marginalization, combined

with a general wondering about the details that might comprise the

experiences. Yet, as the poet, I no longer live either on the edge of

the muskeg or in the apartment from The Blue Dress. I am not

sure, however, if it is possible to view my movement out of the

muskeg and out of the apartment as having escaped those places since

their impact on my identity making and curriculum making remains. A

part of me still experiences that sense of living on the edge of

community explored in this poem. The experience of the experience

(Clandinin & Connelly, 2000) endures and informs my present

experience.

As

a an interim research text,2 based on field texts, both

Muskeg and The Blue Dress function to focus the

researcher-poet on both the experiences detailed in the poems

and the experience of the poems, which is to say “field texts

slide back and forth between records of the experience under study

and records of oneself as researcher experiencing the experience”

(Clandinin & Connelly, 2000, p. 87). As I inquire into these

interim research texts, I learn not only more about the experiences

detailed there but also about myself now, as a researcher, inquiring

into those experiences. The process is ongoing, without a stopping

point. In this way, we are always in medias res—researchers,

poets, and individuals in the middle of our stories to live by even

as we pause to inquire into them.

Beyond

the Edge: Crossing the Boundaries of Identity Within Autobiographical

Beginnings

Old Road

Drift

of exhaust

past

apartments, vacant lots

dusty

from too little rain

reminders

of cool, green scrub brush grown thick (4)

among

blackened stumps barely taller (5)

than

my eleven-year-old head

blueberries

warm with summer’s watching

always

watching

for

bears on the old road

to

the dump.

One

day

my

brothers and I followed that road

past

where it ended in a ditch

cut

crossways to keep cars out.

We

followed it through bush

thick

as planted corn, sometimes

hardly

a track amongst the spruce and poplar

until

we burst out onto a highway (18)

surprising

us, stranding us

up

to our waists (20)

in

Labrador Tea. (Clarke, personal writing, 2013)

The

poem Old Road

demonstrates the inward/outward/forward/backward movement of

narrative inquiry (Clandinin & Connelly, 1994; 2000):

By

inward, we mean toward the internal conditions, such as feelings,

hopes, aesthetic reactions, and moral dispositions. By outward, we

mean toward the existential conditions, that is, the environment. By

backward and forward, we refer to temporality—past, present,

and future. . . . to experience the experience—that is,

to do research into an experience—is to experience it

simultaneously in these four ways and to ask questions pointing each

way. (Clandinin & Connelly, 2000, p. 50)

In

the beginning of Old Road, the perspective is from the

present—the speaker is travelling in a vehicle, experiencing

the smell of exhaust and noticing the urban landscape of apartments

and vacant lots. The vegetation of the vacant lots reminds her of a

different landscape and she moves temporally from the present to the

past through her memories of the “scrub brush grown thick/among

blackened stumps” (Old Road, lines 4-5). Not only does

she move backward temporally but also she moves inward emotionally to

recall her fear of watching for bears on the road leading to the

dump.

The

experience of moving inward and backward produces the recollection of

a specific moment in the poet’s life—the day she explored

the old road with her brothers. The description of their experiences

following the old road beyond the boundaries of their community—“past

where it ended in a ditch/cut crossways to keep cars out” (Old

Road, lines 2-3)—can be read literally. This is a

description of a particular experience, a specific day, and a

specific activity, even a specific landscape, through which the

children traveled to discover what lay beyond their community.

At

the same time, expressed poetically, the articulation of the

experience invites us to think metaphorically about this experience

as well. The children breached the boundary of their community to

inquire into what might lay beyond. Metaphorically, this poem is an

exploration of possibility, of what might exist outside of

established boundaries, both in terms of experience and identity. It

details the emotion associated with the act of stepping outside of

established norms, moving beyond the borders or edges of a community.

It is in the metaphorical contemplation of the experience of border

crossing that the deeper meaning for the poet as an adult emerges.

What is the meaning of the experience of venturing beyond the

boundaries of their community? What might it mean in light of the

descriptions and meanings provided in Muskeg and The Blue

Dress? Taken as a suite of experiences, these poems suggest a

deeper motivation at work in the experiences of the girl and her

brothers. What, if anything, lay beyond the Muskeg?

At

the end of Old Road, the trio “burst out onto a highway”

(Old Road, line 18) as an unexpected outcome of their

explorations. Their surprise prevents them from following the

highway. The image of the trio stranded “up to our waists/in

Labrador Tea” (Old Road, line 19-20) suggests an

inability to move beyond the known into the unknown. The analogy of

being stranded up to their waists in Labrador Tea suggests the forces

at work in the lives of individuals to persuade stasis, to keep a

person in their comfort zone even if that comfort zone is not that

comfortable. The Labrador Tea that surrounds them is a plant

indigenous to the bush of Northern Saskatchewan muskeg. There it is

both familiar and unfamiliar: it is a familiar plant often viewed by

the children along the roadsides, and near their homes on the gravel

pad and unfamiliar because they do not understand its use, its

importance. In this sense, its potential remains a mystery. The

Labrador Tea in the poem is a metaphor for the boundary the children

must pass through to enter into a different community. The highway

the children burst out upon is a surprise and represents the

unfamiliar. The poem suggests that perhaps, for some, living and

learning on the edges of community is more comfortable, more familiar

than venturing beyond the edges or margins into the unknown.

Certainly, the poetic representation of these experiences raises

questions about the boundaries of communities, the forces that

influence individuals to adhere to those boundaries or,

concomitantly, to pass through them, and how the experiences of

living and learning on the edges of community resonate through a

person’s life to create a metaphorical echo that repeatedly

influences identity making. As Caine, Estefan, and Clandinin (2013)

assert, “In a narrative inquiry, stories are not just a medium

of learning, development, or transformation, but also a life”

(p. 578). As we compose narratives, then, we are composed.

Living

In-Between: Navigating Our Multiple Stories to Live By

Innocence

Before

there

were Sunday suppers

spaghetti

with meat sauce

brown

bag lunches with smiling faces

soft

green dresses

patent

leather shoes –

white

gloves for church

white

socks for school.

Before

there

were Halloween pillowcases filled with candy

spruce

trees heavy with tinsel

hand-kneaded

doughnuts, wood stoves, tea.

Every

bed made itself

every

mitten found its mate

every

afternoon started its own fire

to

chase the chill away before supper.

I

still look for smoke

rising

from the chimney

a

familiar face alive

in

the kitchen window

as

the bus pulls away

down

the lane.

In

this final poem of my autobiographical beginning, Innocence

breaks from the previously discussed themes of marginalization and

movement through the borders of community to capture a time in my

life when there was narrative coherence in my experiences and all the

details of those experiences reinforced a sense of belonging and

safety. The irony of the poem, of course, is that it begins by

looking back to a time of easy predictability, immediately suggesting

that the landscape of belonging has shifted and grown into something

decidedly different from the experiences detailed in the first two

stanzas. Stanza 1 and Stanza 2 begin with the temporal benchmark of

“Before” although we are never told “Before”

what. As readers, we can assume an experience so significant that it

makes the experiences detailed in the poem stand out in contrast. It

is here that we see the effectiveness of using poetic representation

as opposed to a prose narrative. In prose, there is an expectation to

complete the thought, to tell or at least show the full story of what

came before, what intervened, and what came after as the conventional

form of a prose narrative. With poetry, it is possible to leave

unspoken the intervening event, creating possibility for the reader

to fill in the gaps with their own experience.

Anyone

who knows me knows that the event of my mother’s death when I

was 17 years old stands as a benchmark for all other experiences in

my life. This is the experience that the “Before” refers

to without explicitly stating it. Interestingly, Innocence

also describes a place, and the human components of that space,

“before” the Muskeg. The scene depicted occurred

as part of my childhood before we moved to the muskeg; however, 10

years later my mother passed away. From that perspective, “Before”

could also refer to life before the muskeg. What we know from the

details provided in the poem Innocence is that there was a

coherence in the experiences of the poet prior to the life event and

that the coherence of those experiences resonates through whatever

came afterwards, so much so that she imagines arriving home to find

the same wood smoke rising from the chimney and the same treasured

person watching for her from the kitchen window. In the sense that

this experience is imagined, it is a forward-looking story

(Clandinin & Connelly, 2000), one that imagines a reconstruction

of narrative coherence in the poet-researcher’s story to

live by. At the same time, it holds within it the seed of a

backward-looking story, the realization that the person she

expects to see there will not be there. The past and the present

exist at the same time in this narrative and through the images

provided by the poet they vie for centrality. Together, the four

poems (Muskeg, The Blue Dress, Old Road, and

Innocence) individually and collectively provide a sense of

from where the researcher-poet comes, from where I come—the

experiences that shaped my identity and that resonate with me today,

informing the relationships I develop with research participants and

the insights and interpretations that grow out of those

relationships.

Brady

(2009) emphasizes the impossibility of remaining objective as a

researcher. In quantitative research, data is said to speak for

itself but, as Brady (2009) points out, “Nothing speaks for

itself. Interpretation is as necessary to human life as breathing”

(p. xi). Brady’s expression of the researcher’s

involvement in interpreting data reminds me of Connelly and

Clandinin’s (2006) emphasis on the importance of

autobiographical beginnings in narrative inquiry. Only when we begin

to understand our own narrative beginnings do we situate ourselves

positively toward understanding the personal and relational

understandings that grow out of narrative inquiry.

Inquiring

into our own narrative beginnings is essential to any research

endeavor. At the same time, trying to maintain a professional

distance from oneself as one attempts to make meaning of one’s

personal narratives leads to a sense of dividedness that is

impossible to suppress. I find it difficult to separate or

compartmentalize my understanding of self into the professional and

the personal as conventional academic discourse suggests that we

should. This is part of the reason why even in my research, poetry

takes a prominent position. I cannot separate my identity as a poet

from my identity as a researcher. The two co-exist in my work in the

same way that they co-exist in my life. For me, being both a poet and

a narrative inquirer means I live in the in-between space where

creative expression and scholarly expression overlap. As Caine,

Estefan, and Clandinin (2013) state: “These in-between spaces

are filled with uncertainty and indeterminacy. They are places of

liminality; the betwixts and betweens, which, we argue, require

attention to context(s), relationship(s), and time to explore

narratively” (p. 580). Like a Venn diagram,3 the

deepening understanding of my stories and the stories of research

participants grows from the spaces in-between creative

expression and scholarly expression where the two circles overlap. In

those spaces in-between from which the poetry emerges, a new

community of understanding forms—a relational community defined

by its overlapping borders while, at the same time, not confined by

them. This wondering from a place of liminality is all part of a

whole that wonders about life in general and seeks to make sense of

life holistically, not one compartment at a time. The children who

come into our classrooms also come with a holistic wondering about

the world and about life as a whole, not just about the subjects we

say are valuable or in the order and timelines that we present them.

In this way, my inability to compartmentalize mirrors children’s

inability to separate themselves from their identity as student and

their identities as daughters, sons, grandchildren, or whatever other

identities they might hold.

As

Trinh T. Minh-ha (1989) says, “Despite our desperate, eternal

attempt to separate, contain, and mend, categories always leak”

(p. 94). In the same way, the categories or compartments of our lives

bleed together, one into the other, until they are indistinguishable

as categories and become the liquid in a fluid process that flows

from one moment to the next without interruption. As researchers who

struggle to separate our own identities into categories, we recognize

the inappropriateness of trying to do the same in our exploration of

the identity making of our research participants, whether they are

children or adults, in a school setting or elsewhere. Identity making

is, by its very nature, complex and ongoing. Our explorations into

identity making should reflect that complexity.

A

Return to the Beginning: Exploring the Researcher’s Identity

Within the Inquiry

As

I consider my own process of identity making and the importance of

understanding my autobiographical beginnings, and as I enter into

these explorations of identity making, I am reminded of the poem

Walking at Brighton by Dave Margoshes (1988). In this poem,

Margoshes (1988) explores the retrospective narrative of a speaker

who recalls feeling on the edges of his familial community, “and

I was a stranger in the family,/always walking behind where the view

is different” (p. 16). I recognize the sentiment expressed in

Margoshes’ poem of being a stranger within your own family. The

community of my family was not a community in which I was

comfortable. Like Margoshes’ speaker, I seemed always to see

things from a different perspective than my siblings or parents,

suddenly and consistently bumping up against my difference and their

difference even though on the surface we shared the same

circumstances.

In

my own family, I lived an experience of exclusion that Clandinin et

al. (2010) detail in the context of dominant school narratives, where

the exclusion of personal narratives excludes and discourages

individuals from seeking connection with those who appear to fit into

the dominant school narrative (p. 449). My sense of disconnect came

not so much from a dominant cultural narrative in conflict with my

identity as it did from a familial narrative that storied me as

separate, as different. The identities that I carried with me, that I

still carry with me, of feeling isolated and separate, apart from

community, are integrally connected to my identity as a curriculum

maker. They are present in the narratives that emerge from my life as

well as in the moments shaped by interaction with colleagues and

children. From my earliest days a binary of self and other was

strongly established in my experience primarily through familial

curriculum-making (Clandinin et al., 2006) moments. From my very

earliest days through my own sense of not belonging to the community

of my family, I began to question the dichotomous positioning of the

centre and the edges of community. I began to wonder which, if any,

group I belonged to or if, in fact, I might belong to both.

Clandinin

et al. (2010) recognize, “Within the institutional landscape,

claiming an identity can be more challenging than passively accepting

one” (p. 473). I suggest it is not only in the institutional

landscape but also in all landscapes, including the family, where

identity making remains a complex and fragile process. In the midst

of this fragile process, I wonder what happens when children’s

sense of themselves is under attack by a dominant narrative that does

not fit coherently with their own. I wonder what it means in terms of

identity making to be excluded so readily and so regularly that the

only comfortable space is the space that excludes. What does it mean

to identity making to recognize yourself as positioned on the outside

looking in or, as Margoshes (1988) frames it, to “always be

walking behind where the view is different” (p. 16)?

Dewey

(1938) suggests context becomes the truths of a present experience,

informing our understanding of narratives as we endeavor to unpack

them. Jackson (1992) also supports an emphasis on context by arguing,

“all experience is necessarily situational and contextualized,

that there is no privileged position outside of experience from which

to achieve a free and independent (i.e., non-contextualized)

perspective” (p. 10). Jackson (1992) acknowledges the presence

of bias in all forms of inquiry and research by stating, “We

begin our search for answers already faced in one direction or

another, our proclivities pre-established, our inclinations

making us lean this way or that” (p. 20). Essentially, Jackson

argues for recognition of a bias by the researcher rather than a

futile attempt to claim objectivity and distance. If we examine the

metaphor of facing in a particular direction, it becomes clear that

we can only see what is within our field of vision—our

perspectives, then, are metaphorically determined by the “field

of vision” defined by the direction in which we look.

Jackson’s

(1992) recognition of probable bias fits well with Dewey’s

(1938) ideas about contextualized perspective. Together they assert

that our perspectives never exist in a void but rather grow out of a

context that turns in one direction or another prior to exploration.

This is not to say that a person cannot turn around to face another

direction. Jackson referred to our proclivity, preference, and

context, intersecting to create a propensity for one position or

another. In Jackson’s (1992) words, “there can be no

position outside interpretation, there is no non-interpretive

stance. There are only ways of looking, a category that includes ways

of looking at ways of looking” (p. 20). Here,

Jackson nods to the multiple layers of exploration that inform our

perspectives as we look and look at how we look—meta-narrative,

so to speak. Our understandings, by their very nature, are at best

personal interpretations.

A

Liminal Life: Both Poet and Scholar

Why

do we choose the threads we choose when we begin to unpack the field

texts from our research? Why do we notice the things we then attend

to? What is it in our own experiences that shape a particular

research experience? Brady (2009) points out, “all research

necessarily starts with an observer moving through the world as a

personally-situated [sic] sensuous and intellectual being”

(p. xi). As the four poems presented earlier demonstrate, each

person, each researcher is personally situated. Our meaning making is

inextricably bound up with our identity and the experiences that we

have and carry with us. My own experiences of living in an isolated

part of Northern Saskatchewan shaped my interest in understanding the

human experience of marginalization, it motivated me to rethink the

way I frame marginalization and to ask whether or not I might see

that space as constructed through identity and experience—as

something determined individually and organically as a result of my

experiences. Although I have provided only four brief moments of my

autobiographical beginnings expressed poetically, they capture the

essence of what has driven me to ask questions about life and

learning on the edges of community. Without exploring my own

autobiographical beginnings, and without exploring them poetically, I

would not understand as deeply as I do who I was, who I am, and who I

am becoming. Furthermore, I would not have as deep an understanding

of the factors related to my identity as a poet and scholar that not

only bring me to these research wonders but also that press me

forward through the larger inquiry itself. In an academy that so

often encourages researchers to strip themselves of all identifying

features, these poetic autobiographical beginnings are essential to

understanding how I position myself within the narrative inquires in

which I engage. They provide a contextual grounding for the

foundational focus of the work that I do. Represented poetically,

these narrative beginnings identify me not as either a poet or a

scholar but as both a poet and a scholar. In this sense, I am no

longer stranded up to my waist in Labrador Tea like the young girl in

Old Road, but rather I have begun to cross the border out of

the muskeg, to move through that boundary and into the community

beyond.

References

Brady,

I. (2009). Foreword. In M. Prendergast, C., Leggo, & P. Sameshima

(Eds.), Poetic inquiry: Vibrant voices in the social sciences

(pp. xi-xvi). Rotterdam, NL: Sense Publishers.

Caine,

V., Estefan, A., & Clandinin, D. J. (2013). A return to

methodological commitment: Reflections on narrative inquiry.

Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 57(6),

574-586.

Clandinin,

D. J. (2013). Engaging in narrative inquiry. Walnut Creek, CA:

Left coast Press, Inc.

Clandinin,

D. J., & Caine, V. (2013). Narrative inquiry. In A. Trainor &

E. Graue (Eds.), Reviewing qualitative research in the social

sciences (pp. 166-179). New York, NY: Routledge.

Clandinin,

D. J., & Connelly, F. M. (1992). Teacher as curriculum maker. In

P. W. Jackson (Ed.), Handbook of research on curriculum (pp.

363-401). New York, NY: Macmillan.

Clandinin,

D. J., & Connelly, F. M. (1994). Personal experience methods. In

N. K. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative

research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Clandinin,

D. J., & Connelly, F. M. (2000). Narrative inquiry: Experience

and story in qualitative research. San Francisco, CA:

Jossey-Bass.

Clandinin,

D. J., Huber, J., Huber, M., Murphy, M. S., Pearce, M., Orr, M. M.,

Steeves, P. (2006). Composing diverse identities: Narrative

inquiries into the interwoven lives of children and teachers.

London, UK: Routledge.

Clandinin,

D. J., Steeves, P., Yi, L., Mickelsoon, J. R., Buck, G., Pearce, M.,

Caine, V., Lessard, S., Desrochers, C., Stewart, M., & Huber, M.

(2010). Composing lives: A narrative account into the experiences

of youth who left school early. Retrieved from

http://www.research4children.com/data/documents/ComposingLivesANarrativeAccountintotheExperiencesofYouthwhoLeftSchoolEarlyFinalReportpdf.pdf

Connelly,

F. M., & Clandinin, D. J. (1999). Shaping a professional

identity: Stories of education practice. New York, NY: Teachers

College Press.

Connelly,

F. M., & Clandinin, D. J. (2006). Narrative inquiry. In J. Green,

G. Camilli, & P. Elmore (Eds.), Handbook of complementary

methods in education research (pp. 477-487). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence

Eribaum.

Dewey,

J. (1938). Experience and education (pp. 33-50). New York, NY:

Collier Books.

Jackson,

P. (1992). Conceptions of curriculum and curriculum specialists. In

P. Jackson (Ed.), Handbook of research on curriculum (pp.

3-40). New York, NY: MacMillan.

Leggo,

C. (2010, Autumn). Lifewriting: A poet’s cautionary tale.

Learning Landscapes, 4(1), 67-84.

Margoshes,

D. (1988). Walking at Brighton (pp. 16-17). Saskatoon, SK:

Thistledown Press.

Minh-ha,

T. T. (1989). Woman, native, other: Writing postcoloniality and

feminism. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Schon,

D. A. (1979). Generative metaphor: A perspective on problem—setting

in social policy. In A. Ortony (Ed.), Metaphor and thought

(pp. 254- 283). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

————

Endnotes

1

The term stories to

live by is a narrative term for

identity used by Connelly and Clandinin (1999) to demonstrate the

connection between narrative and identity.

2Clandinin

and Connelly (2000) describe interim research texts as “texts

situated in the spaces between field texts and final published

research texts” (p.133). Clandinin (2013) explains interim

research texts as a way for researchers to “continue to engage

in relational ways with participants” (p. 47) as they begin the

task of analysis of the field texts. Ideally, interim research texts

are negotiated and even co-composed with the research participants as

the researcher and participants determine together how best to create

a research text that is both authentic and compelling (Clandinin,

2013). Interim research texts, therefore, can often be partial texts

that move the ongoing interpretation from field texts to the final

research text (Clandinin, 2013).

3

Caine, Estefan, and Clandinin (2013) asserte: “Often our

understanding as narrative inquirers does not come instantaneously,

or quickly, or by engaging in clever analysis. Instead our

understanding deepens as we retell and relive our lived stories over

time, place, and social contexts” (p. 581). My experience has

certainly mirrored this sense of deepening rather than an epiphanal

sense of suddenly seeing what was unclear before. This deepening of

understanding occurs as part of the process of the relational

research that is narrative inquiry.

I

first began to explore the themes of the poem Muskeg in

January 2012, thinking about what part of my own life created an

interest to understand the experience of marginalization. In my

journal writing, I reached back to a place where a sense of isolation

and marginalization were most acute. I wrote about my experiences

growing up in Northern Saskatchewan as someone transplanted into that

landscape—a landscape that was, to me, foreign. In retrospect,

however, I realize that the landscape was not foreign, but rather I

was foreign to the landscape. The poem, however, is a deeper

expression of the recollection of being foreign to one’s

surroundings. Muskeg, in its temporal movement between the

past and the present, connects the experiences of the poet as a child

to the experiences of the poet as an adult—to the experiences

of the poet as a researcher. Methodologically, the poetic

representation of those recollections reaches deeper than the

recollections explicated in the journal entries. The poetic form more

richly captures the complexity of those experiences that acted to

shape my identity as a poet and that continue to shape my identity as

a researcher.

I

first began to explore the themes of the poem Muskeg in

January 2012, thinking about what part of my own life created an

interest to understand the experience of marginalization. In my

journal writing, I reached back to a place where a sense of isolation

and marginalization were most acute. I wrote about my experiences

growing up in Northern Saskatchewan as someone transplanted into that

landscape—a landscape that was, to me, foreign. In retrospect,

however, I realize that the landscape was not foreign, but rather I

was foreign to the landscape. The poem, however, is a deeper

expression of the recollection of being foreign to one’s

surroundings. Muskeg, in its temporal movement between the

past and the present, connects the experiences of the poet as a child

to the experiences of the poet as an adult—to the experiences

of the poet as a researcher. Methodologically, the poetic

representation of those recollections reaches deeper than the

recollections explicated in the journal entries. The poetic form more

richly captures the complexity of those experiences that acted to

shape my identity as a poet and that continue to shape my identity as

a researcher.