You Don’t Know Me: Adolescent Identity Development Through Poetry Writing

Janette Michelle Hughes and Laura Jane Morrison

University of Ontario Institute of Technology

Cornelia Hoogland

University of Western Ontario

Modern adolescents exist in a technology-saturated world. Most use smart phones, tablets or computers, or all three, on a daily basis (Madden, et al., 2013). These devices undoubtedly impact adolescents’ identity construction during this critical developmental stage. It is through these devices that students have access to a wide variety of social networking and communication tools with which they can perform their emerging identities.

Using a mixed-methods research approach of qualitative case study analysis, quantitative surveying, Vox Autobiographia, research-voiced poems, and Vox Participare, participant voiced poems, this research investigates the relationship between a multiliteracies pedagogy, poetic inquiry, and the development of adolescent identity. More specifically, this paper focuses on two research questions:

1. How does this group of adolescents use new media tools and social media to create poetry in the classroom and explore their identities?

2. How can we engage learners to become critical producers and consumers of digital texts?

The authors worked with two classes of Grade 9 adolescents aged 14–15, as they reflected on the construction of their various online and offline identities. This was done through a poetry unit that included found, spoken word, and rhyming couplet poetry. In this unit, the students explored current themes in youth culture such as cyberbullying, depression, and body image, and the various experiences that have shaped their identities. They also created their own digital, multimodal texts to represent their understanding of online and offline identity construction. As the researchers facilitated the unit and observed the students during the project, reflecting, writing, and reflecting, the researchers wrote their own poems as part of the poetic inquiry process. Their poems both mirrored the genres taught in class and also incorporated elements of the students’ work in an effort to transform the research process to something more visceral, emotional, reflective, and authentic.

Theoretical Framework

In today’s cultural paradigm, literacy has become, according to Mills (2010), a “repertoire of changing practices for communicating purposely in multiple social and cultural contexts” (p. 247). Students possess a range of literacy experiences and skills that, for the most part, remain untapped in the traditional classroom setting (Lankshear & Knobel, 2003). What is more, students “are accustomed to reading texts that combine image, sound, and words, which are often found in digital spaces that are bound up in social practices” (Hughes, 2007, p. 3). In this way, modern literacy practices have moved beyond the static and two-dimensional (Lotherington & Jenson, 2011) and now combine the multimodal, which is defined as meaning-making through many representational modes (Jewitt & Kress, 2003), and through the digital and the social. We know that identity development is strongly linked to this convergence of social and literacy practices (Alvermann, 2010), which makes it more urgent for schools to incorporate digital social practices and multiliteracies (New London Group, 1996) in the classroom. We must do this in order to engage students and to help them develop strong critical digital literacies skills and a positive sense of self, as Subrahmanyam and Smahel (2012) explain, “constructing a stable and coherent identity is a key developmental task during adolescence” (p. 76).

At the forefront of students’ digital social practices are social networking sites (SNSs). These are defined by Ellison and boyd (2013) as sites that allow students to:

1) create uniquely identifiable profiles that consist of user-supplied content, content provided by other users, and/or system-provided data; 2) publicly articulate connections that can be viewed and traversed by others; and 3) consume, produce, and/or interact with streams of user-generated content provided by their connections on the site. (p. 158)

SNSs are particularly useful in the identity-construction process because they help students develop their “social presence” (Brady, Holcomb, & Smith, 2010). Garrison (2009) defines social presence as the “ability of participants to identify with the community, communicate purposefully in a trusting environment and develop interpersonal relationships by way of projecting their individual personalities” (p. 352). Alvermann (2010) maintains that SNSs facilitate the posturing, performance, and social interaction necessary in adolescents’ identity-construction processes. Jones and Hafner (2012) specifically discuss how Facebook walls are “like stages on which [adolescents] act out conversations with their friends” (p.154) and display their personal preferences, interests, and activities. It is through these literate activities that students are able to exercise their social presence, while simultaneously constructing their identities (Hughes & Morrison, 2013).

Thus, as students’ literacy practices become increasingly multimodal, digital, and social, there is a need not only to include these practices in modern pedagogy but also to teach students how to be critical consumers and producers of digital texts (Selber, 2004). Hobbs (2010) articulates that the point of digital and media literacy is to “simultaneously empower and protect people…we look to [it] to help us more deeply engage with ideas and information to make decisions and participate in cultural life” (p. ix).

Methodology and the Research Design

Setting and Context

The research was conducted in two Grade 9 classes at a secondary school in Toronto, Ontario over a 6-week period. A wide range of students attend the school—from low- to middle-income households and from diverse cultural backgrounds. The gender distribution in each class was unbalanced, making the overall learning environments markedly different. The first class consisted of 17 males and only nine females. Although this was the 9:00 a.m. class, it was the loudest and most boisterous of the two, which made reflective discussion difficult and staying on-task throughout the period an insurmountable challenge. The afternoon class consisted of 15 females and 10 males; in this class it was easier to hold discussions and to guide the students through reflective practice. Gender may have been a factor because schooled poetry experiences for boys “tend” to be contested because they may perceive poetry as a feminized genre (Greig & Hughes, 2009; Hughes & Dymoke, 2011). Interestingly, not all students reported access to technology, mobile devices and/or social networking sites outside of school. This was an important piece of information to obtain from the students because much hype exists in the literature surrounding millennial students and the trope of the “digital native” (Prensky, 2001). As educators, we need to be aware that not all students bring the expertise or comfort with technology we often assume they do. For some of these students, school was the only point of technology access. Yet, prior to the study, the students reported using technology rarely in school and reported never using social networking sites [SNSs] in the learning process or in the creation of their assignments. Some of the learning and authoring activities required students to reflect on their consumption and production practices on these sites; however, those students who did not have a social networking account of any kind were asked, instead, to reflect on their general online consumption and production practices, whether related to social networking or not.

One of the researchers was present throughout the entire 6 weeks as a participant observer, facilitating the poetry lessons, assisting students with the writing process, taking field notes, collecting student work, video recording each session for later viewing, administering the pre- and post-surveys, and conducting the student and teacher interviews. The two other researchers were present at the beginning of the project as participant observers, as well, to gain a more nuanced understanding of the student participants, the dynamics in both classes, and the students’ ability levels. The researchers then participated in the analysis of the data after the unit was completed and all data had been collected. The in-class researcher and classroom teacher co-delivered the poetry unit and graded the students’ process work and their poems.

A description of the participating Grade 9 teacher’s level of knowledge of experience with technology can be summarized in this found poem, based on an interview transcription (December 19, 2012):

You know what you’re talking about.

You can teach them.

But–

A lot of the times–

When teachers–

Well, you know a lot,

So, you have credibility with them.

I’m elderly and

When you try to talk to them about something,

They put up blocks.

They don’t go for it.

They resist.

The study was conducted primarily in the classroom using 14 Android tablets, which were brought in daily by the in-class researcher, and various apps, such as Poetry 101 to learn about poetic genres, devices, and poets/periods of poetry. The students also used the voice recorder and video recorder apps to respond to discussion questions and to record their spoken word poetry. Because the classroom did not have WiFi Internet access, the students also used the school’s computer lab where they were able to access Facebook, the Internet, and various other online digital tools to complete poetry writing and identity-reflection activities. The SNSs were used primarily to examine their social practices within a digital landscape, what kinds of messages they consume and produce, and how these impact their identity development.

Selection Process

Convenience sampling was used to select the two classes. One of the researchers had previously done a teaching placement at Oakwood, so she knew the participating teacher and asked him if he would be interested in participating in the project. The students in both classes and the teacher filled out consent forms prior to the start of the study. The students were told both verbally and on the forms that they had the right to decline participation in the study and that this would not negatively affect their grades. They were also told that if they so chose, they could discontinue their participation in the study at any point (during or after).

For the purposes of this article, three students were purposively selected for close case study analysis, two from the morning class and one from the afternoon class, in order to demonstrate the range of understanding and synthesis that presented across the two classes. The students chosen for the case studies were exemplary in either their understanding or lack of understanding surrounding identity construction, and the effect of poetry and social media in this process.

Data Collection and Analysis

Our research team used a qualitative research approach that employed a combination of poetic inquiry (Prendergast, Leggo, & Sameshima, 2009) and in-depth case study analysis (Stake, 2000). Because the research design required students to engage in identity exploration and construction using new media and poetry, it was fitting for the research team to engage in poetic inquiry as an investigative method in order to get closer to the participants and to better understand their experiences. Importantly, poetic inquiry has the power, as Ellis (2004) explains, to help readers “keep in their minds and feel in their bodies the complexities of concrete moments of life experience” (30). It was necessary to use an approach that would best capture and communicate the challenges of the writing and identity-exploration process for the students, and we wanted our research process to mirror the process the students were engaging with as well.

Our team produced a combination of research-voiced (Vox Authobiographia) and participant-voiced (Vox Participare) poems based on our classroom observations, field notes, interview transcripts, and the students’ own poetry (Prendergast, 2009). We wrote a selection of multivoiced poems using the poetic forms taught to the students during the poetry unit—thereby creating a parallel between our research focus and the dissemination of our findings. We relied on performance ethnography and poetic inquiry (Denzin, 2003; Prendergast, Leggo, & Sameshima, 2009) and created in “forms that others will want to read, watch, or listen to, feel and learn from” (p. 262), such as “drama, poetry, and narrative” (Glesne, 2010, p. 245). This layered, metacognitive process was an ideal way to connect with the students’ work and to reflect on the research on emotional, imaginative, and visceral levels.

Finally, our case study methodology, which included an examination of the students' writing, the transcribed interviews with students and teachers, and the digital and multimodal texts created by the students, allowed our team an in-depth look into the teaching and learning practices that emerged during the project. As Bruce (2009) points out, case studies “provide the best articulation of adolescents’ media literacy processes, especially as much of the emergent forms of their use has not been studied” (p. 302). In the case study analysis, we employed Strauss and Corbin’s (1990) traditional coding procedures to code the student interview transcripts and then used Black’s (2007) cross-case comparison to examine common emergent themes across the selected case study samples. Thematic coding (Miles, 1994) and critical discourse analysis (Fairclough, 1995) were also used when examining the data sources. As major and subthemes emerged, the codes were revised and expanded. During the data analysis, we were particularly interested in what Bruner (1994) identifies as “turning points,” looking for areas where the students presented themselves differently and started to develop an awareness of the identity-construction process and/or what it means to be media producers and activists rather than simply consumers.

The Research Design

The Digital Activities, Identity Exploration, and Poetry

Students revisited basic poetic devices using the Poetry 101 app and sharing their knowledge through group activities. They then learned about the following genres of poetry over the course of six weeks: found poetry, spoken word poetry, and rhyming couplet poetry. To study poetry and to construct their own poetry, they used Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, the skoool.ie website for interactive poetry, and the Android Poetry 101 app.

As a way of scaffolding their understanding of identity development, the students were introduced to the definition of identity, how one constructs his or her various online and offline identities, the differences and similarities between the two, and why this distinction is important. This was done through in-class activities that included visual representations and metaphors of online and offline identities, comparison charts, Venn diagrams, and small and large classroom discussions.

Found poetry. Launching into the found poetry genre, the students were provided with an example of a poem constructed entirely from Facebook status updates and asked to determine what kind of person the author might be projecting based on the types of status updates s/he posts. Following this, the students created a found poem based on their own status updates, and/or comments, or the status updates and/or comments from their “friends.” Depending on what material they chose, the students were asked to reflect on either what kind of personae they project on Facebook or what kinds of messages they are constantly exposed to on Facebook. During this process, the researchers wrote their own found poems reflecting on the students’ writing processes and their emergent understanding, or lack thereof, of multiple identities. To construct these poems, the researchers used words and phrases borrowed from the students’ poetry. Found poetry was particularly important to include in the research design because it draws on Knobel and Lankshear’s (2008) assertion that the remix is so inherently a part of our modern, digital life.

Spoken word poetry. The students were then introduced to the emotionally charged genre of spoken word poetry through three different examples on YouTube: Alicia Keys, the R & B artist Ani DiFranco, who is also a known spoken word artist, and the 2005 National Poetry Slam Finalists. After watching these examples, the students were asked to reflect on the following: What made this particular genre so engaging? What were some effective poetic devices used in this genre? Why were they effective? What themes or topics work best with spoken word poetry? After analyzing the genre, the students brainstormed youth issues that were important to them and wrote and recorded their own spoken word pieces. Simultaneously, the researchers composed spoken word pieces based on what they observed of the students during the writing process and what was and was not working in the project to date. Spoken word was important as we drew on Jewitt’s (2008) assertion that experiencing literature in a multimodal digital environment (where image, text and sound come together in one surround) adds layers of meaning that might not be conveyed in a strictly print format.

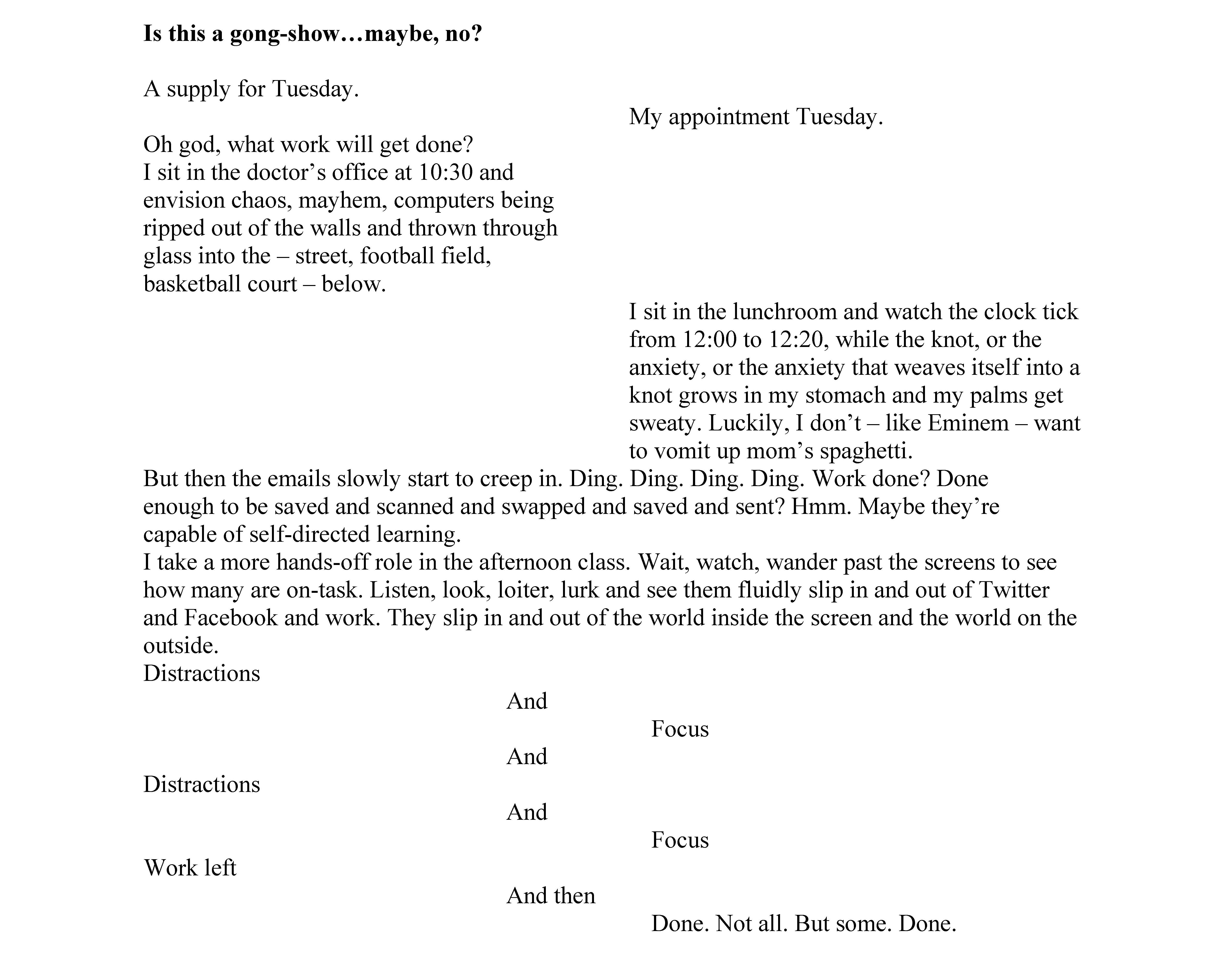

Rhyming couplet poetry/rap. Finally, the students were introduced to the rhyming couplet genre through the skool.ie interactive poetry website, which focuses on W.B. Yeats’ poem “When You Are Old.” Students read and listened to the poem, and answered questions on the poem’s theme, rhyming structure, imagery, poetic voice, metaphors, similes, and symbols. Again, the researchers wrote their own rhyming couplet poetry based on what transpired during the teaching and learning process. At this point in the project, the students were getting restless with the work-intensive process involved in analyzing and writing poetry and this restlessness started to have an impact on the in-class researcher. Interestingly, this was reflected in the researcher’s poetry where a frustrated voice begins to surface:

Found 1

The problem is clear

And, Just because I’m smiling, doesn’t mean I’m happy.

I Have

An Involuntary nervous system that stiumulates the pace of the heartbeat.

So, What’s on my mind?

Pick up every piece of MY shattered heart

I Know There Are Ways to get things off My mind: do yoga, relax...rather than

worrying.

What our society is today, I honestly can’t say.

AHHH! Monday morning...again.

At the conclusion of the research project, the students were given a consolidation activity and the choice of writing either a found, spoken word, or rhyming couplet poem on one of the following topics/writing prompts: I am what I am, relationships rebooted, love/friendships gone digital, or changing identity. Most students chose to write in the found or spoken word genre.

The Findings and Discussion

For the most part, our research team was met with many challenges as we guided the students through the process of self-reflection and identity exploration. Their initial lack of self-awareness is represented in the following research poem written in Week 3 of the study, after a variety of identity-reflection activities had been organized to prime the students’ understanding of identity construction and multiple identities. The poem represents the metaphorical wall the researcher hit due to a lack of observable “turning points” (Bruner, 1994) in the majority of students’ understanding:

DAY SIX/DEEP SIX:

so, what are the different 'hats' you wear in your everyday life?

well, I don't wear these types of hats, well, I'd wear

that toque, but that's the only one.

oh...I don't know.

ok, well, you play different roles depending on the context you're in, right? do you play any sports? are you involved in any clubs?

yea i play sports

ok, so which ones?

basketball, baseball, lacrosse...

ok, and what positions do you play...what role do you play on this team?

team captain

assistant captain

defense

ok, so you probably have different responsibilities...you probably act differently as a team captain than you do in your role as student, right?

(blank stare) i guess...

*thud

Going into the project, we were aware that the two classes had little experience with formal identity reflection and/or new poetry genres such as found poetry or spoken word, based on the students’ pre-surveys and preliminary conversations with the teacher. However, it was only once the study began that our team became aware of the extent to which the students thought (or did not think) critically about the factors that have influenced their identities and their identity-construction process. It was here we also became aware of how challenging it would be to use poetry to engage them in this reflection process, because many students associated poetry with that which is inaccessible and irrelevant to their lives. Certainly, none of the students initially saw where poetry, new media tools, and social media could converge to assist them in identity reflection and construction. They were not, at first, aware of how their different domains or discourse worlds (lifeworlds and school-based worlds) are instrumental in their identity-creation process (Cope & Kalantzis, 2000), or how the activities in which they engage in their Lifeworlds, such as their social networking practices, help to shape their literate identities. They were not aware that they could draw on these literate identities “when engaging in literate practices” (Antsey & Bull, 2006, p. 34), such as poetry writing, to further develop each student’s voice, sense of self, and agency.

However, a turning point did come when we introduced both classes to the found poetry genre and encouraged the students to reflect on how they construct their online personalities—what they edit out, choose to include, what kinds of messages they are constantly exposed to from “friends” or advertisements. While the students still encountered some difficulty in the learning and writing process, it was clear that they connected with the use of a social networking account as a metacognitive reflection and writing tool. This is demonstrated in the following observational poem written by one of the researchers when she observed one of the first turning points:

This was a particularly important change to witness in the students, because up to this point, it had been very difficult to bring their attention to, and reflection on, this philosophical question of identity. It had also been difficult to engage the students in the idea of writing poetry to explore their writerly voices—or helping them to see the different factors that influence their identity, such as new and social media. Found poetry worked well as a way for students to examine critically the messages they leave and receive in their social networking accounts. It was an accessible entry point into poetry writing, as it allowed them to use extant words and phrases, which meant that they were saved from the cognitive overload and frustrations of writer’s block.

The Case Studies: Markus, Jane, and Anita (all names are researcher-selected pseudonyms)

It was at approximately this halfway point in our study that three students stood out as exceptional. Two of the students demonstrated obvious turning points in finding voice through the poetry-writing process and seeing how the use of new media, social media, and poetry could come together to help them in the identity-development process. Essentially, in these two students we witnessed a development in their literate identities and also in their abilities to become critical consumers and producers of texts.

Case Study 1: “I Have Aged Everyday”

Markus was a shy, relatively quiet boy at the start of the project; however, the research team observed many turning points for him over the course of the study. These turning points were made apparent through the poetry he created, the divergent answers he provided on his pre- and post-project surveys, and the answers he provided in his interview regarding poetry, technology, and identity development. He was one of the students who did not participate in social media of any kind nor did he have a personal email address or access to much technology at home. In an informal in-class discussion, he shared that he had minimal access to a computer at home.

The pre-/post-survey. The pre-project survey asked if “social networking sites such as Facebook or Twitter can help you develop online identities that help you grow?” He responded, “I do not feel social networking sites can help you grow personally” (November 7th, 2012). However, after the poetry unit and an exploration of how one’s environment and social connections impact identity development, when asked the same question on the post-project survey, this time he replied: “It could help you grow because over the years, you will grow and learn [from what is recorded]”(December 20th, 2012). This was a significant turnaround in perspective and indicated to the research team that within a relatively short amount of time, approximately six weeks, this student developed an awareness about how new and social media can impact the identity-construction process, when the exploration is done in a formal, focused and reflective educational setting.

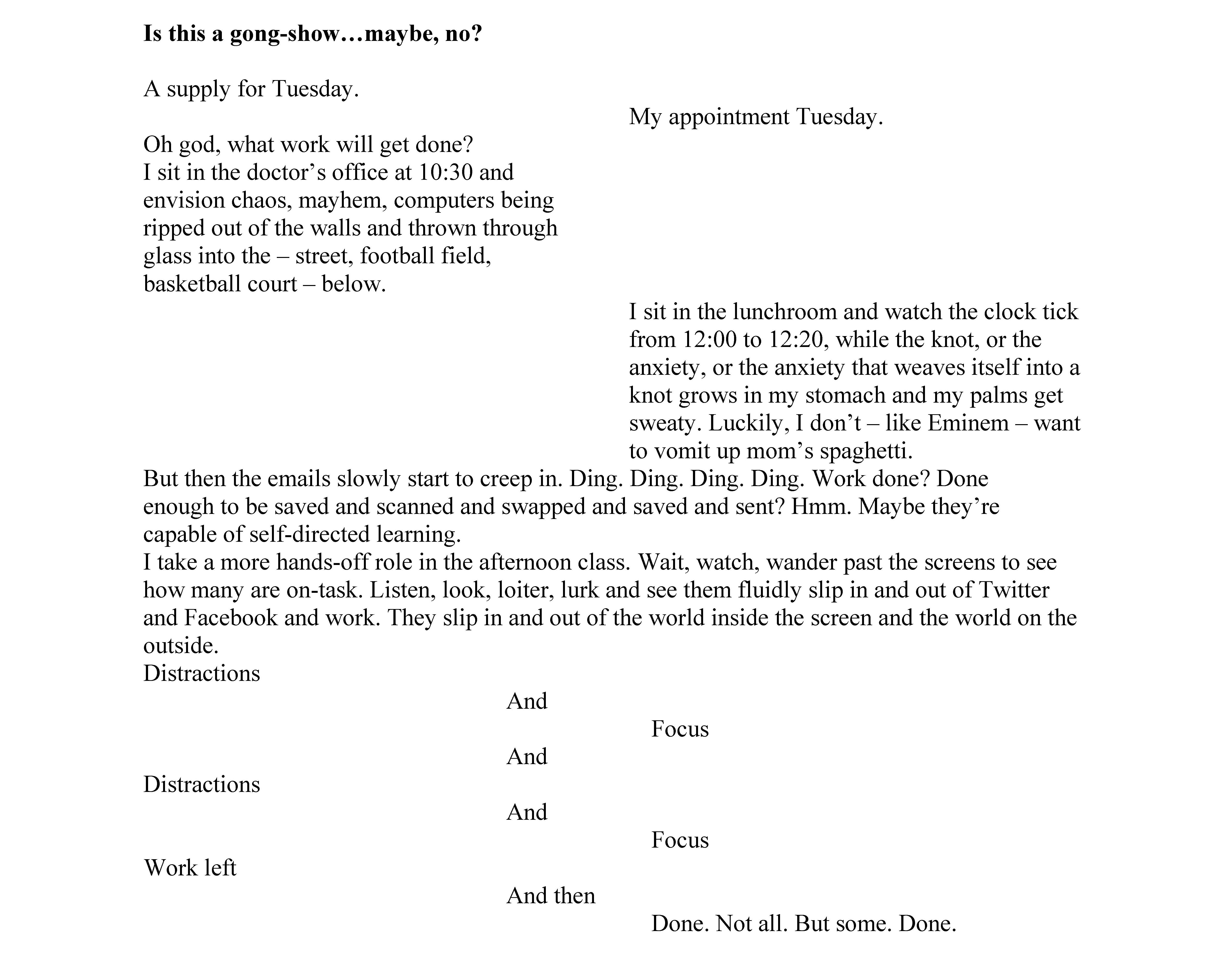

The poetry. From the beginning of the research study, Markus’s insightfulness was clear based on the comments he would share in class. From his poetry, the research team began to see the extent to which he was internalizing our classroom discussions and activities surrounding identity construction. In an informal conversation with one of the researchers, he explained that he enjoyed writing poetry and that it helped him express himself. The following example is one of the rhyming couplet poems he created to explain the process of maturation as he had experienced it thus far:

Like a puppy to a dog

Like a tadpole to a frog

They’ve grown up in a way

I have aged every day.

realizing in my mind

that I have embarrassed myself many times

comparing to actions today

those memories will stay

To the man I now talk to

To the boy I now mock to

Over time, responsibility will grow

Over time to the money I will soon owe

To be big and so proud

I feel that I’m on the 9th cloud

The fact that I fear

To mature more is much near

Figure 1. Markus’s rhyming couplets poem

As a precursor to creating this poem, the students were asked to use the web-based learning tool, skoool.ie, to read and analyze W. B. Yeats’s poem “When You Are Old.” This new media tool allowed the students time to reflect on the aging and maturation process through its guiding and interactive functions, while also demonstrating the rhyming couplets rhyme scheme. The new media tools used in the study, such as skoool.ie, engaged Markus, as he explained in his interview that he found it was easy to express himself using poetic language, devices, and this rhyming form in particular. The multimedia tools and the poetry format allowed him the creative space to explore his poetic voice and reflect on his own maturation limbo that he recognized in himself as a new Grade 9 student.

The interview. Another turning point we witnessed was in Markus’s post-project interview where he shared what he learned about himself from the project, what insights he gleaned about the identity-construction and voice-finding processes from engaging with new media, social media, and the poetry-writing process. When asked if he learned anything about himself from the project, he shared that he was he was able to reconnect with a poetic voice he had not used in a while, but one that he valued: “I used to actually write a little bit of poetry when I was younger. I kind of found…myself, you know, kind of liking poetry again, which was pretty nice. I feel a little bit more calm, relaxed” (December 19th, 2012). This affirmed for us the value of using poetry to help guide the students through the identity-reflection process because the creative expression inherent in poetry provides a unique space for students to connect with the poet that exists in everyone; poetic language is everywhere and part of the human psyche (Brady, 2009), but may be dormant. Once Markus had reconnected with his poetic voice, allowing him the agency to express himself, he reported feeling more “calm, relaxed” (December 19th, 2012).

Furthermore, when it came to the technology, Markus admitted to enjoying the intersection of new media tools, social media, and the poetry unit. He said, “I really enjoyed the tablets, like I enjoyed how you can record the poems, and, like the video, and the audio…[Regarding] social media, I think not many people for actual class work can actually go on Facebook and Twitter” (December 19th, 2012). Markus played around with the recording features of the tablets and was able to use them to record audio and video versions of his poems, particularly the spoken word poem. This was unique as the new media literally allowed the students’ voices to be projected. Markus found agency in the control he was able to exert over the rhythm and pacing of his poem when he performed or recorded it on the tablet. By the end of the six weeks, it was obvious that Markus had found a new way to express himself and a new literate voice in which he felt a sense of power and agency—two important elements in an adolescents’ process of identity construction.

Case Study 2: “I Want People to See Both Sides of Me”

Jane was another student in whom we witnessed a similar transformational process. Jane was a conscientious student and very intelligent; however, at the beginning of the project she did not stand out as an outspoken or particularly confident individual. As the poetry unit progressed, however, and as she had opportunity to share her thoughts, opinions, and knowledge through her poetry and through our in-class discussions on identity, a more assertive and self-assured voice emerged.

The post-survey. When asked on her post-survey, “Do you now feel technology can help students develop their sense of identity? If so, how?” Jane responded, “I feel technology can help students develop their sense of identity because they can explore their utmost personality in different aspects” (December 20th, 2012). Jane appreciated the multimodal affordances of the new media tools, which can help students express themselves in a variety of ways. For instance, the tablets allowed the students to combine text with speech and images in order to respond to tasks and poetry-writing assignments in class. Jane went on to explain that social media can help students to “show themselves as a whole not just one aspect of their personality. They become their true selves or they become the opposite of how they are” (December 20th, 2012). After our concentrated exploration through poetry of how one edits and constructs his or her personal profiles on social networking sites, this was the conclusion Jane came to. By the end of the project, she had begun to develop a critical eye toward the messages she both receives and produces in digital social spaces. She elaborates on how social networking sites can aid in the identity-development process by explaining:

The activity online helps you express who you are and what you are like to others because you can only show one aspect of your personality for example some people are very social and outgoing. But in the real world you could be a very shy person. So activity online helps us express who we are but only to a certain extent. (December 20th, 2012)

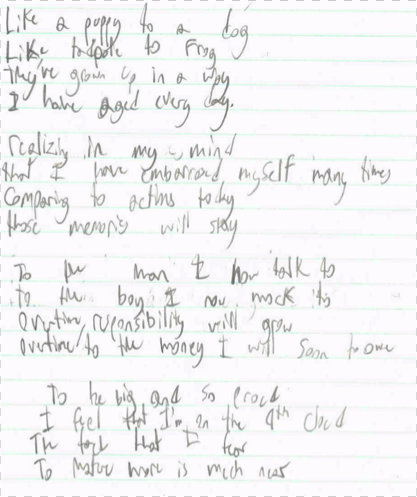

The poem. While Jane, like Markus, appeared to be an insightful student, her voice developed differently over the course of the project. Where Markus’s focus was on his personal maturation process, Jane explored her interest in political issues and developed her social justice voice through the poetry writing assignments. This is demonstrated most fully in the following found poem:

Figure 2. Jane’s found poem.

Much of the other work done in this grade nine class had little to do with politics, so Jane had not had the opportunity to express this side of her personality in the classroom. The poetry unit allowed her to merge her out-of-school interests and literary practices with her in-school assignments, by using new media, such as the Internet, to find inspiration and simultaneously explore and analyze the information she is exposed to most often in her digital practices.

The interview. By the end of the project, Jane was attuned to the various identities she had constructed in her life and what has impacted the development of these identities. Unlike the majority of the students in the class, when asked how many identities she had, she confidently responded by saying: “I would say around four,” having taken the time during the poetry unit to reflect on all of them. In an informal conversation, she elaborated on what these identities were: one identity for friends, one for family, one identity as a student, and one for social media. This awareness is important as it ultimately translates to a strong sense of self and agency.

Case Study 3: “Online or in Real Person…I’m Very the Same”

On the other end of the spectrum was one student (Anita) who stood out for her staunch rejection of the idea that individuals have multiple identities and that factors such as new media or social media could play a role in the identity-construction process. Anita was a very social and bubbly student in the classroom. She was clearly well-liked by her peers, but not exceptionally critical when it came to analyzing the poetry in class or peeling back the layers involved in the identity-construction process.

What was particularly interesting was that this student completed all the assignments and wrote all the required poems to a satisfactory, if not high standard, unlike some of the other students who did not understand or “buy into” the premise of the research/study unit. This indicated for the research team that there was still a lack of self-awareness between the development of the students’ literate identities and their ability to be critical consumers and producers of texts.

The post-survey. On her post-survey, Anita demonstrated that she had been unmoved in her opinion of identity construction. When asked, “Do you feel technology can help students develop their sense of identity? If so, how?” She responded with a straightforward, “No.” Similarly, when asked, “Do you feel social networking sites such as Facebook or Twitter can help you develop online identities that help you grow? If yes, please explain.” Again, she responded with a resounding and singular, “No.” This was an interesting finding and it highlighted the need to include identity construction as it relates to new and social media in the curriculum and to investigate further, why students feel this way about their online identity. It is clearly an important issue and there is evidently a need to bring students’ awareness to this issue in order to help them consciously create positive selves—armed with the awareness of what factors influence the development of one’s identity, for the better or worse.

The poem. Although Anita did not believe that technology, new media, or social media could help develop a student’s identity, she engaged in all the poetry writing and reflection activities and created a lighthearted, yet telling, poetic voice throughout the unit. This can be seen in her poem entitled, “What I am”:

What I am

I am young

I am fun

I like to shop

I like to drink pop

You are old

You are NOTE bold

You don't spend money

You are not funny.

I am teen

I am lean

I love to gossip

I like gloss on my lip

You are forty

You are not a party

You like the news

You wear comfy shoes

I don't get up till ten

I want TV in the den

I do my nails

I look for sales

I am what I am

You are what you are

We are what we are

No one can change that

Figure 3. Anita’s rhyming couplets poem.

Anita, along with other students who did not understand the convergence of social media, new media and identity construction, was still willing to explore the topic of identity through a unit on poetry. She, like other students, indicated that she appreciated the creativity involved in writing poetry and was able to develop a distinct poetic voice during the project, drawing on her literate identity, part of which is constructed in her out-of-school new and social media practices. In retrospect more work should have been done with students such as Anita to help them make this connection in order to help them develop critical awareness.

The interview. In her post-project interview (December 19th, 2012), she explained how she enjoyed the poetry unit, but echoed the firm beliefs previously expressed on her survey. When asked, “What did you like or dislike about the poetry unit?” She explained that she “liked the creative element” and that she “liked being able to communicate in a different way than we normally do in school.” This was similar to what both Markus and Jane communicated in their post-project feedback—explaining that they enjoyed using the multimodal media tools and using the creative format of poetry to explore and express themselves. Anita appreciated that there was an intersection of her out-of-school literary practices and her in-school literary practices in this project. This indicated that part of her engagement in the poetry, part of the reason she bought into the poetry unit, was because new and social media tools added a fresh dimension that spoke to her out-of-school literate identity. She confessed to learning something new about herself through the unit, saying “I learned that I like, I just like writing poetry now because I like expressing myself through that.” So, she was able to explore and develop her identity, however, by the end of the study, she was still unable to see the connection between new media and social media and one’s process of identity construction.

At one point in the interview, Anita offered that the new media tools helped her discover a part of her identity and present her poetic voice: “I liked [the tablets] because it was different from presenting it to the class and you can like do different things and not be embarrassed about how you sound or the way that you look.” However, when asked again in the interview if she learned “anything about your different identities?” She held firm with: “Not really, I’m kind of the same.” Even when questioned on social networking sites and if they might help one develop his/her identity, she retorted with: “No, not at all…because it’s the Internet and it’s just, it’s just there. It doesn’t really do anything. I guess it’s been there my whole life. It’s not really a big [deal].” This was an important and telling statement, as it highlighted for the research team how close millennial students are to new and social media—they are so intertwined with these cultural tools that some may not have the distance necessary to see how the tools might shape identity construction. It is very difficult to be a critical consumer and producer when one is proximally so close.

Conclusion

The study made clear that new/multimedia and social media were powerful tools for engaging this group of students in the reflective poetry-writing process. The multimodality of the new media tools honoured the students’ out-of-school literacy practices and allowed them to express themselves in ways that were comfortable, familiar, and/or to express things that could not simply be captured in the written word. Furthermore, incorporating the inherently reflective structure of a social networking site, which logs one’s online social history, helped facilitate the identity-reflection and exploration processes.

However, the study also highlighted the fact that over 50% of the students in both classes were largely unaware of their multiple identities, particularly the differences in their online and offline selves, and how these selves were constructed. Through this, we discovered that most of the adolescents in these classes were operating blindly in their online activities; unaware of how their social literacy practices affected their identity development. Weber and Mitchell (2008) remind us that identity construction is a fluid process that “constantly sheds bits and adds bits, changing through dialectical interactions with the digital and non-digital world, involving physical, psychological, social and cultural agents” (43). As a result, moving forward, we see an urgent need to incorporate online identity construction and critical digital literacies into the curriculum in order to help adolescents develop positive online and offline identities, equipped with agency and critical thinking skills.

The poetic inquiry methodology enabled the research team to connect with the students’ work on a new, metacognitive level where we were writing our own poetry based on the students’ poetry. As we incorporated their words and phrases into our own work, we felt a deeper connection to, and insight into, their cognitive and writing processes. In the following research poem, all the words and phrases were taken from student-generated poems and were arranged to communicate the chaos and confusion, and yet the hopefulness, the researcher experienced at one point in the study:

Life is a carnival

But

She just doesn't get it

He just doesn't get it

But

Impossible is nothing.

Using their words and voices, the research team was able to gain better insight into the students’ inner landscapes and emotions. Where we may have otherwise glossed over certain words and phrases, incorporating the students’ work into our own poetry gave us time to reflect on what the students were trying to communicate through their poems.

Furthermore, writing poetry after each day encouraged us to reflect on what had transpired in the classroom, during the teaching and learning process. It was an engaging and therapeutic way of gaining perspective as we recorded what went wrong, what worked, and what needed to change for future lessons and projects. Writing the poetry also helped us reflect on the writing process for the students. While it was relatively easy for the researchers to sit down and write, taking the time to do this allowed us the space to consider how challenging it might be for some of the students to write poetry. We realized that more scaffolding and support was necessary to facilitate the writing process.

To conclude, in our experience, when steps were taken to show students how their online social practices help shape their online and offline identities, we were met with resistance from many. From this, we reasoned that for these students, their digital and physical worlds have become so intertwined that they do not possess the emotional or philosophical distance necessary to internalize this “big-picture” concept. As a result, we see room for future studies to examine how best to include the exploration of online identity construction in the English classroom in order to discourage the “disembodied user” (Subrahmanyam & Smahel, 2012) and develop critically and digitally literate adolescents.

References

Alvermann, D. E. (2010). Adolescents’ online literacies: Connecting classrooms, digital media, & popular culture. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Anstey, M., & Bull, G. (2006). Teaching and learning multiliteracies: Changing times, changing literacies. Newark, NJ: International Reading Association.

Black, R. (2007). Digital design: English language learners and reader reviews in online fiction. In M. Knobel & C. Lankshear (Eds.), A new literacies sampler (pp. 115–136). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Brady, I. (2009). Foreward. In M. Prendergast, C. Leggo, & P. Sameshima (Eds.), Poetic inquiry: Vibrant voices in the social sciences (pp.13–29). Rotterdam, NL: Sense Publications.

Brady, K., Holcomb, L., & Smith, B. (2010). The use of alternative social networking sites in higher educational settings: A case study of the E-learning benefits of Ning in education. Journal of Interactive Online Learning, 9(2), 151-160.

Bruce, D. (2009). Reading and writing video: Media literacy and adolescents. In L. Christenbury (Ed.), Handbook of adolescent literacy research (pp. 287–303). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Bruner, J. (1994). Acts of meaning: Four lectures on mind and culture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Cope, B., & Kalantzis, M. (Eds.). (2000). Multiliteracies: Literacy learning and the design of social futures. London: Routledge.

Denzin, N. K. (2003). Performance ethnography: Critical pedagogy and the politics of culture. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Ellis, C. (2004). The ethnographic I: A methodological novel about autoethnography. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira.

Ellison, N. B., & boyd, d. (2013). Sociality through social network sites. In W. H. Dutton (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of internet studies (pp. 151-172). Oxford, ENG: Oxford University Press.

Fairclough, N. (1995). Critical discourse analysis: The critical study of language. London, ENG: Longman Publishing Group.

Garrison, D. R. (2009). Communities of inquiry in online learning: Social, teaching and cognitive presence. In C. Howard et al. (Eds.), Encyclopedia of distance and online learning (2nd ed., pp. 352-355). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Glesne, C. (2010). Becoming qualitative researchers: An introduction. New York, NY: Longman.

Greig, C., & Hughes, J. M. (2009). A boy who would rather write poetry than throw rocks at cats is also considered to be wanting in masculinity: Poetry, masculinity, and baiting boys. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 30(1), 91-105. doi: 10.1080/01596300802643124

Hobbs, R. (2010). Digital and media literacy: A plan of action. Washington, DC: The Aspen Institute.

Hughes, J. (2007, October). Poetry: A powerful medium for literacy and technology development. . What Works? Research into Practice Series. The Literacy and Numeracy Secretariat, Ontario Ministry of Education. Retrieve from http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/literacynumeracy/inspire/research/Hughes.pdf

Hughes, J., & Dymoke, S. (2011). “Wiki-Ed Poetry”: Transforming Preservice Teachers’ Preconceptions About Poetry and Poetry Teaching. Journal of Adult and Adolescent Literacy, 55(1), 45-46. Retrieve from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1598/JAAL.55.1.5/pdf

Hughes, J., & Morrison, L. (2013). Using Facebook to explore adolescent identities. International Journal of Social Media and Interactive Learning Environments,1(4), 370-386. doi: 10.1504/IJSMILE.2013.057464

Jewitt, C. (2008). Multimodality and literacy in school classrooms. Review of Research in Education, 32(1), 241–267. doi:10.3102/0091732X07310586

Jewitt, C., & Kress, G. (2003). Multimodal literacy. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Jones, R. H., & Hafner, C. A. (2012). Understanding digital literacies: A practical introduction. New York, NY: Routledge.

Knobel, M., & Lankshear, C. (2008). Remix: The art and craft of endless hybridization. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 52(1), 22-33.

Lankshear, C., & Knobel, M. (2003). New literacies: Changing knowledge and classroom learning. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press.

Lotherington, H., & Jenson, J. (2011). Teaching multimodal and digital literacy in L2 settings: New literacies, new basics, new pedagogies. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 31, 226-246. doi: 10.1017/S0267190511000110

Madden, M., Lenhart, A., Cortesi, S., Gasser, U., Duggan, M., Smith, A., & Beaton, M. (2013, May 21). Teens, social media, and privacy. Retrieved from http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2013/Teens-Social-Media-And-Privacy.aspx

Miles, M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded handbook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Mills, K. A. (2010). A review of the ‘digital turn’ in the New Literacy Studies. Review of Educational Research, 80(2), 246-271.

The New London Group. (2005). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66(1), 60-92.

Prendergast, M. (2009). Introduction: The phenomena of poetry in research–‘Poem is What?’ Poetic inquiry in qualitative social science research. In M. Prendergast, C. Leggo, & P. Sameshima (Eds.), Poetic inquiry: Vibrant voices in the social sciences (pp. 13-29). Rotterdam: Sense Publications.

Prendergast, M., Leggo, C., & Sameshima, P. (Eds.). (2009). Poetic inquiry: Vibrant voices in the social sciences. Rotterdam, NL: Sense Publishers.

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital native, digital immigrants. On the Horizon, 9(5), 1-6.

Selber, S. (2004). Multiliteracies for a digital age. Carbondale, Ill: Southern Illinois Press.

Stake, R. (2000). Case studies. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 435–454). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory, procedures and techniques. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Subrahmanyam, K., & Smahel, D. (2012). Digital youth: The role of media in development. New York, NY: Springer.

Weber, S., & Mitchell, C. (2008). Imagining, keyboarding, and posting identities: Young people and new media technologies. In D. Buckingham (Ed.), Youth, identity, and digital media (pp. 25-48). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.