Exploring the Experiences of a Small Group of Saskatchewan Neophyte Aboriginal Teachers

Laurie-ann M. Hellsten, University of Saskatchewan

Jane P. Preston, University of Prince Edward Island

Michelle P. Prytula and Danielle P. Jeancart, University of Saskatchewan

Research indicates that in the United States up to 50% of beginning teachers leave the profession within their first five years and of that number between 20 to 30% leave within the first three years of starting their teaching career (Ingersoll & Smith, 2004; Kelley, 2004; Maciejewski, 2007; Suydam, 2002; Villani, 2002; Voke, 2002). Of the limited Canadian research on this topic, a study conducted in 2011 speculated that of the 75% of Alberta Bachelor of Education graduates who obtained a teaching contract following graduation, one-third were likely to quit within their first five years in the profession (Nolais, 2012). Novice teachers experience difficulties adjusting to school culture and expectations (Khamis, 2000). These early experiences set standards that guide beginning teachers for the rest of their careers (Moir & Gless, 2001) and have implications for teacher effectiveness and career length (McCormack & Thomas, 2003). Due to the Baby Boom, many teachers are currently approaching retirement age, thereby intensifying the point that increasing numbers of new teachers will be entering public schools within the near future. Retaining quality classroom teachers is critical to the success of schools, yet this is becoming an increasingly challenging task.

With regard to ethnicity and teaching, Aboriginal[1] peoples are the fastest-growing Canadian ethnic group, and Statistics Canada (2011) estimated that by 2031 up to 5% of the Canadian population will be Aboriginal, as compared to the present level of 3.4%. The greatest provincial increase in the Canadian Aboriginal population is expected in Saskatchewan, where the Aboriginal population is circa 15% (Statistics Canada, 2008). This provincial population is expected to reach 24% by 2031 and 33% by 2045 (Steele, 2011). This burgeoning population provides budding opportunities for increased numbers of Aboriginal people to enter the teaching profession. Across Canada, there is a call to actively recruit, hire, and retain Aboriginal people into the teaching profession (Preston, Cottrell, Pelletier, & Pearce, 2012; Hardes, 2006; St. Denis, 2010).[2] Although some studies have explored the dynamics of Aboriginal teachers’ professional experiences in Canada (Friesen & Orr, 1996; Legare, Pete-Willet, Ward, Wason-Ellam, & Williamson, 1998; St. Denis, Bouvier, & Battiste, 1998; Wotherspoon, 2008; Wimmer, Legare, Arcand, & Cottrell., 2009), and other research has documented the experiences of beginning teachers in Saskatchewan (Hellsten & Prytula; 2011; Hellsten, Prytula, Ebanks, & Lai, 2009; Prytula, Hellsten, & McIntyre, 2010), few, if any, studies have focused specifically on the experiences of Aboriginal beginning teachers in Saskatchewan public schools. Furthermore, few studies have specifically focused on the needs of Aboriginal teachers. Of the limited resources available, Wimmer et al., (2009) stated, “Evidence points to the need for higher education, and especially teacher education, to become better informed about the concerns of Aboriginal peoples and to be more responsive to their needs” (p. 817). One goal of our research, as demonstrated in this paper, is to respond to this research void.

The purpose of this paper is to highlight the professional experiences of selected Aboriginal neophyte teachers in Saskatchewan, Canada. The results of this research aim to identify and elaborate on the personal and professional supports for beginning Aboriginal teachers. Providing neophyte Aboriginal teachers with the resources they need has potential to influence teacher recruitment, employment, and retention rates in positive ways. As well, the results of this study have the potential to inform teacher education programs on how best to prepare teachers to meet the needs of students effectively.

Background Literature

Across Canada, there is a pronounced need for more Aboriginal teachers (Preston et al., 2012; Ball, 2004; Greenwood, de Leeuw, & Fraser, 2007; St. Denis, 2010). In addressing this lack of Aboriginal teachers, information about teacher recruitment, teaching experiences, and retention rates needs to be highlighted and addressed. St. Denis (2010) indicated that Aboriginal teachers face similar challenges to non-Aboriginal teachers, including issues of retention. Across all sectors, the teaching profession reflects a higher turnover rate than that of most other professions (Watts Hull, 2004). Thus, not only do educational systems need to be concerned with recruiting greater numbers of Aboriginal teachers but also the retention of these beginning teachers is of particular concern (Ingersoll, 2001; Watts Hull, 2004). In many schools, the high turnover and attrition rates of teachers directly influence a school division’s inability to support consistent, high-quality teaching. Research suggests that teachers with less than five years of experience are not as effective as teachers with more than five years of experience (Croninger, King Rice, Rathbun, & Nishio, 2007) and that teacher turnover negatively impacts student achievement (Ronfeldt, Loeb, & Wyckoff, 2013). Because many teachers leave the profession within the first five years, classrooms are akin to recurrent training grounds, where teachers with some experience leave the profession before becoming experts. In turn, they are replaced by novice teachers who, due to their lack of experience, perpetuate the cycle and impede the promotion of master-level teaching (Hellsten & Pryula, 2011). Otherwise stated, recruitment and retention of teachers are closely linked to teacher efficacy, which positions recruitment and retention as factors directly influencing student achievement (Mueller, Carr-Stewart, Steeves, & Marshall, 2011).

In addressing the issue of teacher retention, the following question arises: What places beginning teachers at risk of leaving the profession? Although there is a paucity of research that specifically targets Aboriginal teachers, there is much research focusing on neophyte teaching experiences in general. Prior to entering the teaching profession, studies indicate that preservice teachers are both optimistic about finding employment (Snyder, Doerr, & Pastor, 1995) and idealistic about their future careers (Martin, Chiodo, & Chang, 2001). Most new teachers indicate they feel prepared for their first year of teaching (McPherson, 2000), and that they intend to remain in the teaching profession (Ontario College of Teachers [OCT], 2003). Counterbalancing this constructive attitude, the majority of beginning teachers are then startled by their initiation into the teaching profession (Le Maistre, 2000; McPherson, 2000; Simurda, 2004). Beginning teachers often enter their first year with a similar teaching load and responsibilities to those teachers with many years of seniority (Angelle, 2006). Consequently, beginning teachers often feel overwhelmed by the demands of the profession (OCT, 2003; O’Neill, 2004; Russell, McPherson, & Martin, 2001). Other new teachers feel both isolated and immobilized by the challenges they face (Rogers & Babinski, 2002). Canadian survey results indicated that almost all new Ontario teachers were dissatisfied with the resources and support they received during their first year (McIntyre, 2004; OCT, 2003). Nolais (2012) reported that the high demands of teaching amounted to an average of 56 working hours per week—a fact which likely also influences the high teacher attrition rates. In sum, heavy teaching load, lack of sound mentorship, lack of personal support, and lack of resources are underlying reasons why teachers leave the profession after only a few years.

Theoretical Framework: Aboriginal Concept of Community

According to Absolon and Willet (2005):

One of the most fundamental principles of Aboriginal research methodology is the necessity for the researcher to locate himself or herself. Identifying, at the outset, the location from which the voice of the researcher emanates is an Aboriginal way of ensuring that those who study, write, and participate in knowledge creation are accountable for their own positionality. (p. 97)

Adhering to Indigenous research protocol and Aboriginal ways of knowing, we feel it is necessary for us to position ourselves in this work. The research team is a group of four women, who work alongside each other in teacher education. Three of us locate ourselves as outsider researchers because we are non-Indigenous researchers and educators writing about Indigenous education. One of us locates herself as an insider/outsider researcher because she is a Métis woman who works in the field of Aboriginal education, but she has never been a student of an Aboriginal Teacher Education Program. Together, we have held a variety of roles in education, including classroom teacher, school administrator, faculty, and university administrator. We acknowledge that we are speaking from a place of privilege by participating in the academy; however, we approach this research from the perspective of being greatly invested in anti-racist and inclusive education, and greatly committed to improving teacher education and the experiences of beginning teachers.

We have used the Aboriginal concept of community to help analyze the findings of this study. The Aboriginal concept of community is one of interconnected wholeness, or, as succinctly said by Atleo (2004), “Everything is one” (p. xi). From an Aboriginal standpoint, healthy and strong communal relationships are vital for survival (Wilson & Wilson, 1998). We specifically highlight communal features embedded within an Aboriginal worldview to help to examine and understand the results of this study. We were led by the participants’ worldview to describe the data as they explained it.

Chilisa (2012) explained that decolonization is “a process of conducting research in such a way that the worldviews of those who have suffered a long history of progression and marginalization are given space to community from their frames of reference” (p. 14). Kovach (2009) acknowledged that Aboriginal knowledge has been marginalized within Western research processes. Such Westernized research hegemony is about promulgating Westernized realities and value systems (Absolon, 2011; Battiste, 2008; Chilisa, 2012; Smith, 2012; Wilson, 2008). One reason why we use the Aboriginal concept of community as an analytical framework for the research is to attempt to situate our research in a somewhat decolonized location. Also, in relation to this point, one of the four authors of this paper has an Aboriginal heritage. The non-Aboriginal authors have attempted to learn from the knowledge of the Aboriginal author, which also aligns with the concept of community.

As part of a larger project on beginning teachers in Saskatchewan, we felt it was important to provide opportunities for all beginning teachers to participate and to share their thoughts and perceptions about their experiences. Thus, we specifically recruited participants across a number of characteristics, including Aboriginal ancestry, in order to represent the population of teacher candidates in Saskatchewan programs more fully. In considering the findings of the larger study, we as a team recognized that although similarities between non-Aboriginal and Aboriginal participants existed in terms of the challenges and opportunities raised by participants, there appeared to be a level of uniqueness with respect to the Aboriginal findings that might be disregarded if included only as part of the larger study. In our study, we intentionally attempted to ensure that the voices of the Aboriginal beginning teachers were not muted and we purposefully privileged Aboriginal knowledge and experience (St. Denis, 2011).

Research Methodology, Data Sources, and Analysis

This study is part of a larger program of research that focused on the experiences of beginning teachers in Saskatchewan (Hellsten et al., 2009). Extrapolating from the larger study, in this research, we used a mixed method research approach in an attempt to highlight the experiences of a small group of Aboriginal neophyte teachers. We selected a triangulation design (Creswell, Plano Clark, Gutmann, & Hanson, 2003) “to obtain different but complementary data on the same topic” (Morse, 1991, p. 122). We used descriptive analyses based on the demographic survey data (conducted first) and then we used open-ended survey items and the interviews to explore the variables of interest in greater detail. The interviews were also used to provide thick description (Denzin, 1989). The numerical and textual results were compared to generate pragmatic findings and implications. Although our research methodology is considered Westernized in paradigm (Kovach, 2010; Wilson, 2001a), we are “bringing together diverse ways of knowing and doing at the pragmatic level” (Botha, 2011, p. 323) only. Furthermore, our holistic approach means that no one source of information (i.e., demographic data) is considered in isolation (Absolon & Willett, 2004). We believe our desire for the findings to be solution-focused (Absolon & Willett, 2004) and contribute to “change out there in the community” (Weber-Pillwax, 2001) helps to alleviate some of the tension between our western methodologies and Indigenous research methodology.

We invited beginning teachers who graduated from a teacher education program in 2005 or 2006 to complete a survey and/or be interviewed. One hundred and twenty-five teacher education graduates completed the survey questionnaire and 12 beginning teachers were interviewed. Survey participants were asked to respond to items pertaining to demographic characteristics, educational and job search experiences, level and type of mentorship, and current employment experiences. In particular, the latter point targeted a description of workload, perceptions of success, and teaching challenges. Survey items included numerical and Likert-type items as well as open-ended questions. In this paper, we focus on the 18 participants who, in the survey data, self-identified as having graduated from an Aboriginal Teacher Education Program.[3] To complement the survey data, we have included the qualitative interview results of the two volunteer participants who identified as having graduated from an ATEP program. Interview participants were asked a series of reflection questions about their current employment situation (e.g., How did you decide to become a teacher? Who or what influenced your decision?), their initial teaching experiences (e.g., What is it like to teach at your school? How would you describe your overall workload as a teacher?), their preparation and supports (e.g., What kinds of support have you received as a beginning teacher?), and teaching as a career (e.g., What have you liked most about your job so far?). On average, interviews took about an hour to complete.

Survey data were entered into the IBM SPSS program. We thematically analyzed both the open-ended survey items and the interviews by creating a preliminary list of key ideas, commonalities, and differences, which converged into broader themes in response to the study’s purpose (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Creswell, 2012). Although the processes of coding the transcripts and interpreting the codes were data driven, constructed from the raw information contained in both the open-ended items and the transcribed responses of the interview questions (Boyatzis, 1998), we still attempted to consider both the mundane and the exceptional (Fine, Weiss, Wesson, & Long, 2003) and avoided focusing solely on the negative (Struthers, 2001). In doing so, we tried to avoid interpreting and representing ideas that only “buttress stereotypes, reaffirm the ideology and rhetoric of the Right, and reinscribe dominant representations” (Fine et al., 2003, p.185).

Results

In what follows, we present the survey and interview data. Survey data documented the participants’ demographic information, professional experiences, and views about the challenging aspects of the profession. The qualitative findings present issues surrounding the participants’ success in obtaining a teaching position, the beneficial supports encountered during the first year of teaching, and the challenges of first year teaching.

Survey Results

A number of key findings pertained to the teaching realties of neophyte Aboriginal teachers in this study. These findings related to the age of the teachers, the geographical locations of their residences, and the challenges they experienced during the first year of teaching. These and other issues are explicated below.

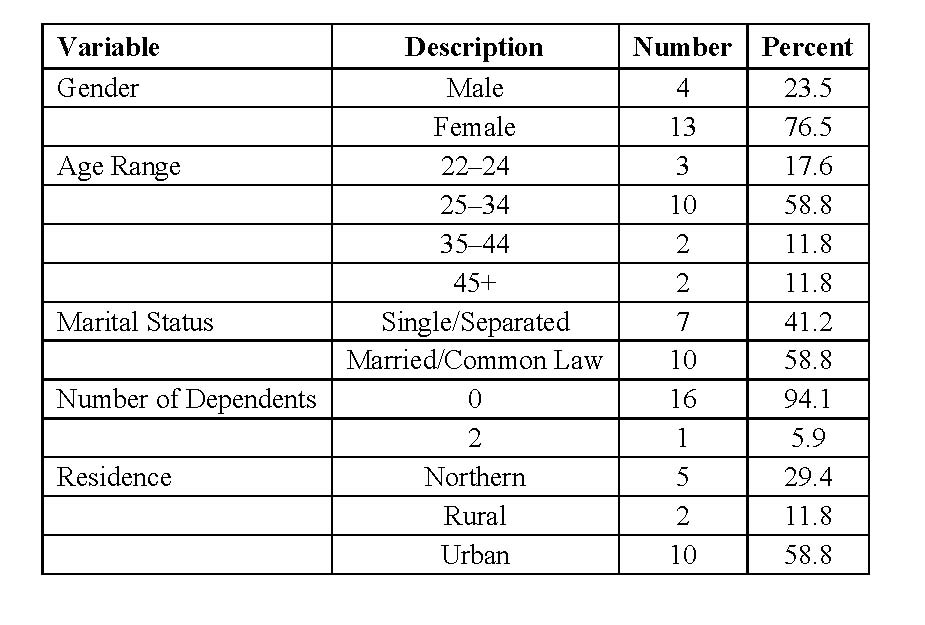

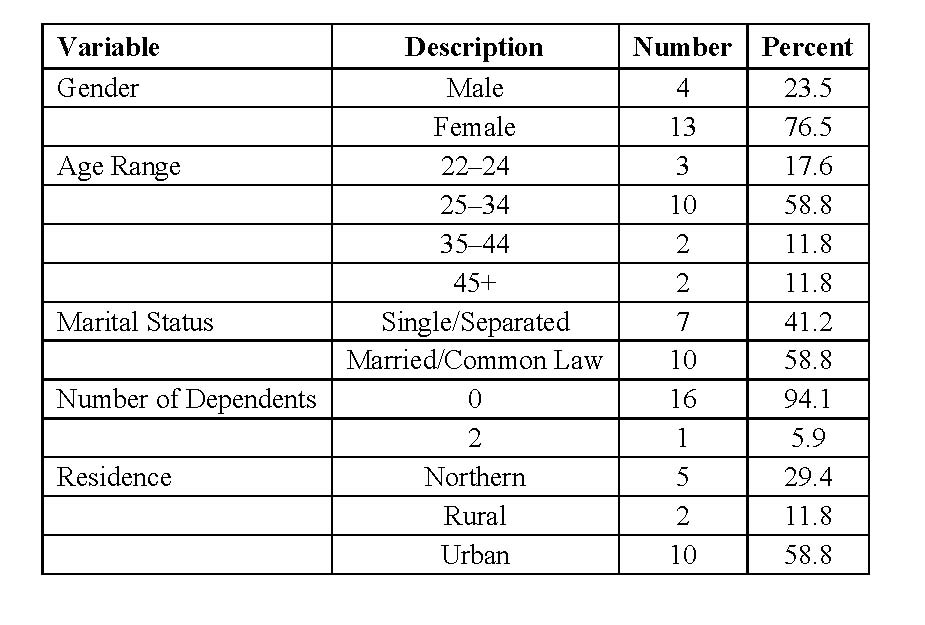

Numerical data. As mentioned previously, 18 participants who self-identified as having graduated from an ATEP program participated in the survey. Of these Aboriginal participants, the majority were female (77%), between 25 – 34 years of age (59%), had no dependent children (91%), and resided in an urban context (59%), (See Table 1 for an overview of this information).

Additional survey data showed that, although the educational training of survey participants ranged from early childhood to secondary settings, most beginning Aboriginal teachers were trained to teach in elementary or middle-school classrooms. Specializations in subject matter varied widely and included Native Studies, Cree, English, Kinesiology, Art, and Biology. All participants held a valid teaching certificate from Saskatchewan, from the Northwest Territories, or from both. Eleven of the participants were employed as teachers (10 full-time), five were actively substitute teaching, one was employed as an Assistant Aboriginal consultant in a First Nations school,[4] and one participant obtained a position outside of the field of education. Of the 10 full-time teachers, three held permanent contracts, one was on a replacement contract, and six were on temporary contracts. Four of the 10 full-time teachers were teaching in First Nations schools. Participants’ first year teaching experiences varied and ranged from teaching in Aboriginal Head Start preschool programs to teaching Grade 12 students.

Table 1

Aboriginal Survey Participant Characteristics

As a group, participants taught single and split-grade classrooms and facilitated multiple-grade and multi-subject assignments. Participants also taught students with diverse needs, and, in some situations, participants taught in classrooms where more than half of the students were on modified programs. Over half of the participants (67%) stated that they had a mentor. In describing the role of their mentor, participants explained that mentors were involved in modeling best teaching practices (61%), observing classroom teaching (50%), and assisting with student discipline (28%). One participant spoke specifically of how her mentor “took her onto the land to learn among the Elders.” When asked why they chose teaching as a profession, the top two reasons selected as “very important” or “important” were “to make a difference” (100%) and “to work with young people” (94%). Another participant noted that the “natural gifts acquired through teaching (i.e., Native women as teachers)” motivated her to become a teacher.

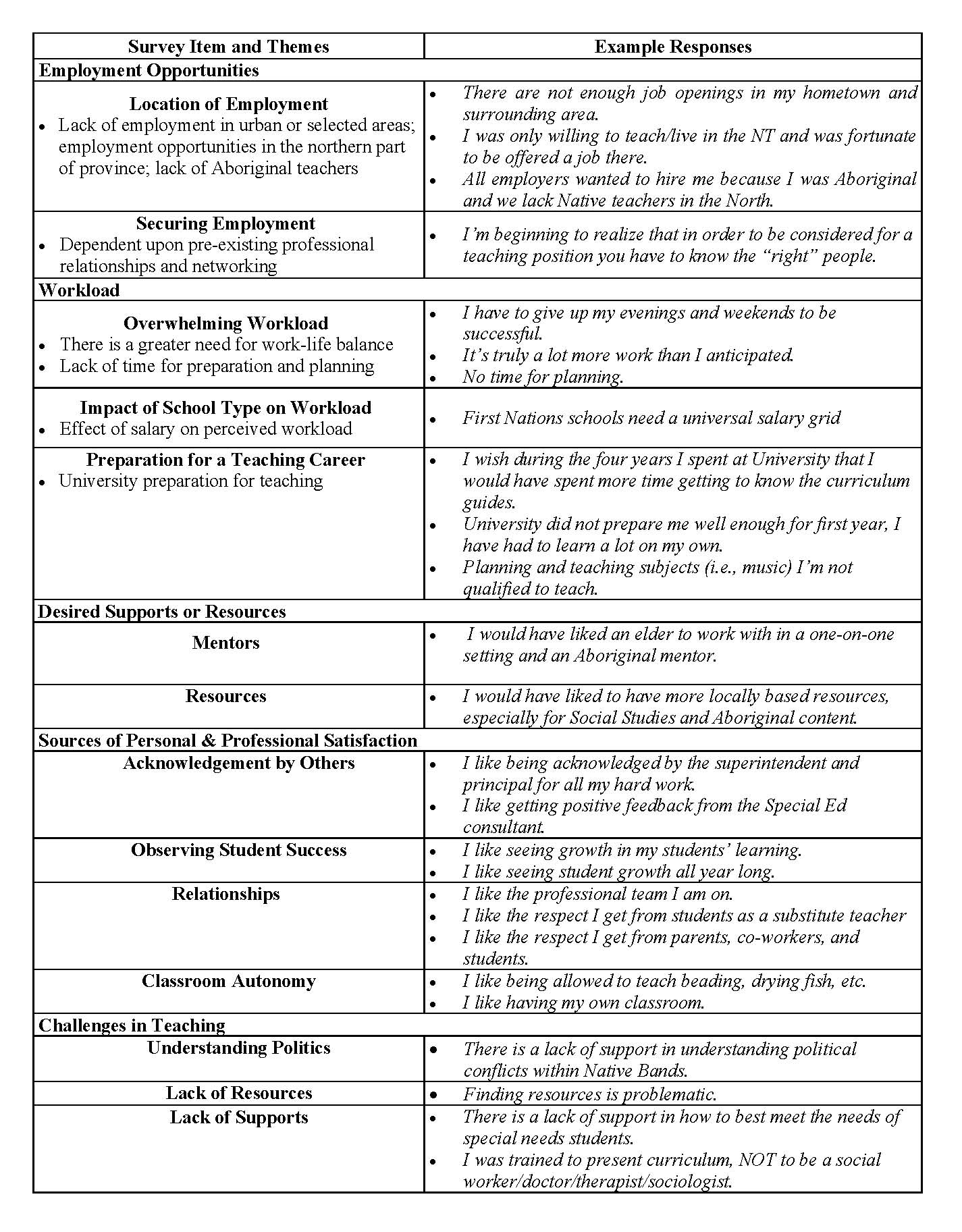

Open-ended items. Through five open-ended survey questions, participants described their first year teaching experiences with a particular focus on employment opportunities, teaching workload, desired additional supports, personal and professional satisfaction, and challenges. For each question, at least 33% of participants provided detailed written responses, which were thematically summarized. The open-ended survey topics and the resulting thematic answers are highlighted in Table 2.

The topic of the first question referred to employment opportunities; participants indicated that there was a lack of teaching jobs in some areas (e.g., urban centers) and a greater abundance of employment in Northern Saskatchewan. In general, their job search experiences underscored a need for Aboriginal teachers in schools, but they perceived that their ability to obtain employment was largely dependent upon the pre-existing professional relationships they had previously created and secured. The second item focused on teaching workload. Participants generally appeared to view their workload as overwhelming; consequently, they saw a desperate need for greater work – life balance. Some participants believed that the teacher education program did not adequately prepare them for their first year of teaching, and that this lack of preparation added to their workload because they were forced to figure things out on their own. For at least two respondents, perceived workload was impacted by salary and the inequities between the provincial K-12 and band-operated school salary grids.

With respect to the item regarding desired supports and resources, participants identified the need for mentors (i.e., Elders, Aboriginal teacher mentors) and for resources with more Aboriginal content. The fourth item focused on participants’ four main sources of personal and professional satisfaction: (a) acknowledgement by others for a job well done, (b) observing student success, (c) relationships with others (e.g., students, parents, co-workers, and administrators), and (d) teaching autonomy (e.g., ability to teach traditional Aboriginal curriculum such as beading and having responsibility for own classroom). When identifying challenges, participants emphasized three issues: (a) lack of professional support, (b) lack of resources, and (c) need to better understand band politics.

Qualitative Interview Findings

With regard to the qualitative aspect of this study, a number of themes surfaced. These themes addressed motivational aspects of teaching and spotlighted some of the successes and challenges neophyte Aboriginal teachers experienced. These themes and a description of the participants are provided below.

Table 2

Thematic Summary of Answers to Open-Ended Survey Items

Description

of interviewed participants.[5]

Two 1st-year

teachers who self-identified as graduates of an ATEP program

volunteered to participate in a phone interview. During the time of

the individual interviews, both Aboriginal teachers were just

completing their first year of full-time teaching. Brianna[6]

was an elementary teacher, in the 25‒34 years of age category,

and self-identified with full treaty status. She was a mother of two

young children and had teaching specializations in Biology and

History. At the time of the interview, she was employed on a term

contract with a provincial Kindergarten to Grade 6 school located in

Northern Saskatchewan. Although not originally from the community

where she was teaching, she and her children, at the time of the

interview, resided in the town where the school was located. Fewer

than 500 people populated the town, but it bordered two larger

communities—a First Nations community and a non-First Nations

community consisting of around 1,000 people each. Brianna’s

school enrolled approximately 300 students and provided a variety of

programs including Cree language instruction and traditions. Brianna

was the Grade 2 teacher in a classroom of 18 children who exhibited

diverse learning needs. Brianna spoke highly of the school,

describing it as “a good school” where “teamwork”

thrived, within a “community-focused” environment.

Brianna said that her school was “always doing something, not

only on weekdays but [also] on weekends too.” She characterized

herself as “goal oriented,” a “hard-worker,”

and “very organized,” and she hoped to be teaching at

this school long into the future.

Mark was the second ATEP graduate interviewed. Following employment in the financial sector, Mark graduated with teaching specializations in Native Studies and English. Mark was in the 35–44 years of age category, single, and moved into the urban community in which he was teaching. At the time of the interview, he was completing his first year teaching Grade 6 in an urban public Kindergarten to Grade 6 community school. Like Brianna, Mark was teaching on a full-time term contract; thus, he had yet to solidify his plans for the following year. Mark’s school was newly built with approximately 250 students enrolled. Twenty-eight students were in his Grade 6 classroom, including 19 boys and nine girls. Several of these children were identified as having special needs (e.g., a child with autism and a child with multiple disabilities). Mark described his school as having a number of “different programs happening.” He stated that his colleagues described him as having “administrative potential” and not “a typical first year teacher.” Mark explained that he wanted to have a long teaching career.

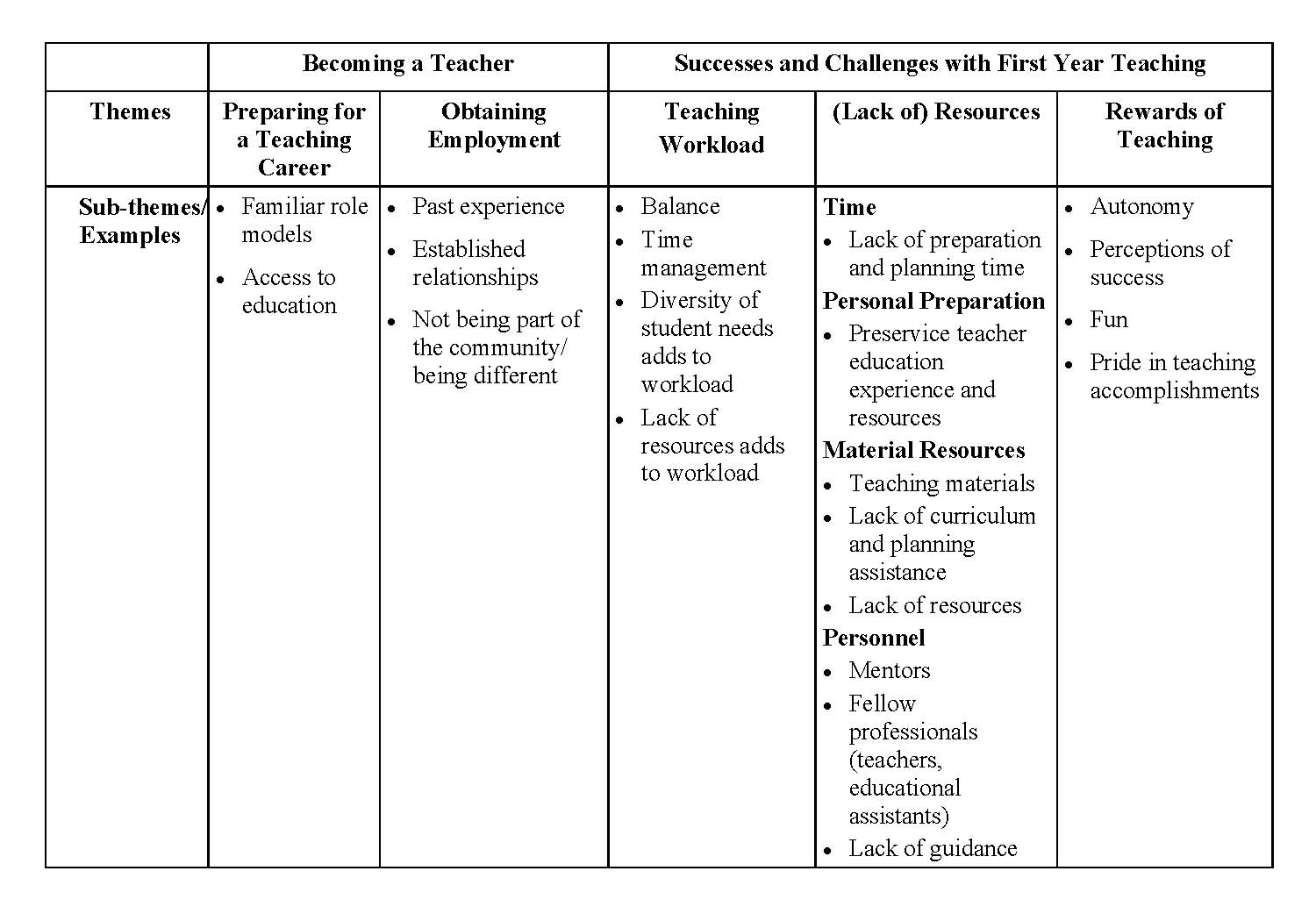

In analyzing the qualitative interviews, two categories of themes emerged. The first theme was Becoming a Teacher. On this topic, participants talked about preparing for a teaching career and obtaining employment. The second theme focused on the Successes and Challenges with First Year Teaching. As participants discussed the successes and challenges of first year of teaching, three dominant themes emerged centering on the topics of teaching workload, resources (including lack thereof), and the rewards of teaching (see Table 3).

Table 3

Themes and Sub-Themes Surfacing in Qualitative Data

Becoming

a teacher. Brianna and Mark talked about why they had decided to

become teachers and how they obtained their first job. Both Brianna

and Mark identified familial role models as significantly influencing

their decision to become a teacher. Brianna stated, “I have an

aunt and a sister who are both teachers so that made me more

interested [in teaching as a profession]. They inspired me.”

Access to education influenced Brianna in her decision to become a

teacher. Although she had considered other career options, ultimately

Brianna chose teaching because, “It [the Bachelor of Education

program] was offered in the North, and I didn’t want to move

far from home.” Two things influenced Mark's decision to become

a teacher: his lack of motivation in his former job and his sibling.

“I was in banking for 12 years, and I decided to change career

paths. My sister…is a teacher and has been for the past 18

years.”

With regard to obtaining their first teaching positions, Brianna and Mark believed that their past experience and pre-established relationships played a role in their successful job searches. Although Brianna was not from the community where she ultimately obtained her teaching position, she believed she was selected, in part, because of an established relationship. Brianna explained, “I interned in the school so I had a better chance, because they knew me.” However, Brianna stated that she felt she was scrutinized, because she was not from the community and because of her Aboriginal identity. Furthermore, Brianna did not think her Aboriginal background was advantageous in her job search at the time of her application. In fact, Brianna declared that, “I'm a full treaty Aboriginal woman. There really aren't that many [full treaty Aboriginal teachers]. There may be one other in the school so I think that worked against me.”

Brianna went on to explain that, although she believed the requirements had since changed, at the time of her hiring, there was no required quota of Aboriginal teachers to Aboriginal students. Ultimately, Brianna credited her job to the successful work she did in her internship. She explained, “I tried very hard when I was there in my internship, and I was recognized for it.” In contrast, although Mark also was not from the community where he worked, he resided “about five minutes from it” and he did not think the location of his residence mattered. Mark stated that his current principal “…worked with my sister for eight years.” Mark believed the strong reputation of his sister was advantageous to him gaining employment.

Successes and challenges with first year teaching: Resources. Brianna and Mark described the types of resources they found to be most beneficial and the types of resources they found lacking in their first year of teaching . Sub-themes emerged relating to: (a) material resources, including the availability of or lack of teaching materials, and a lack of curriculum and planning assistance; (b) personal resources, as characterized by perceived preparation or a perceived lack of preparation for the teaching profession; (c) temporal resources, as related to having/not having sufficient preparation or planning time; and (d) personnel resources, such as having access to mentors and educational assistants resources.

In terms of beneficial material resources, Brianna and Mark identified the teaching materials and unit plans gleaned from fellow teachers as one of their most valued resources. Brianna received teaching resources from the teacher who formerly taught Brianna’s class. On this point, Brianna said, “She … left everything. She didn't take one thing out of that classroom. So that made it easier for me as a first-year teacher in the K to 6 system.” Mark was appreciative of the teaching materials the Grade 4/5 teacher gave to him. On this topic, he said, “Mrs. [White], the Grade 4/5 teacher, she gives me resources and things to look at.” However, with regard to resources, Mark made an interesting comment: “You had to figure out who was going to help you and who wasn’t.”

Both Brianna and Mark identified personal preparation such as relevant university assignments and experiences as contributors to their successful first year of teaching. Brianna completed her Aboriginal teacher education program mostly in her Northern Saskatchewan community. She believed these classes helped her to learn the cultural aspects threaded into many Northern Saskatchewan schools. She viewed the local delivery of these courses as valuable, because they successfully prepared her for the cultural realities of her current students. Mark described particular university assignments as extremely useful and relevant. “All of my lesson and unit plans that I had made over those years were for Grade 5 and 6, and I actually ended up using them. They pulled me through the first couple of months.”However, Mark also mentioned that he “felt ill-prepared” for his first year of teaching. He stated, "I don't think that I was as prepared as I could've been” and, as a result, he felt he had a lot to learn on the job.

As indicated above, Brianna and Mark were thankful to the teachers who provided them with guidance about curricular issues, lesson plans, and unit plans, yet, they desired more assistance in this area. There was, however, a lack of assistance that contributed to insufficient time for planning and preparation. For example, Brianna wanted assistance in creating year plans because it was mandatory in her school that each teacher create a year plan for each subject taught. She explained that the concept of writing year plans was not adequately addressed in her university courses. Consequently, she spent much valuable time researching what a year plan was, getting samples of year plans, and determining time allotments for chunks of the year plan. Brianna also wanted assistance with unit planning and said, “I can't even remember how many unit plans I've done [at university], but I would've liked to do more.” Mark expressed a need to have more familiarity with curricula and unit planning. He explained, “Because curriculum guides are so important, I wish we had classes that spent more time exploring curriculum guides and everything in them.” With regard to unit planning, he said:

As a first year teacher, I haven't had time to sit down and write my own units. I'm out there searching for existing units, apart from the ones that I had written on my own during my four years. But I don't feel like I have time to think about writing my own units. (interview, April 2007)

Brianna and Mark indicated that finding the time to decipher curricular documents and the amount of time spent creating unit plans were some of the most difficult aspects of their first year of teaching.

Brianna and Mark identified various school personnel as being key to their success as new teachers. Brianna described her mentor as being an important professional resource to her in that the mentor provided her with many teaching resources. In contrast, Mark identified his educational assistant as a crucial person in his classroom; he stated, “I don’t know what I would do without her.” In describing how the educational assistant helped him, Mark explained, “She helps me a lot with my correcting, so she saves me a lot of hours doing this even though it’s not in her job description to do it.” In comparison, Brianna's key resource person provided her with material resources, while Mark's key resource person provided him with additional time.

Brianna and Mark also described a lack of guidance with regard to the physical structure of the school and to the dominant teaching protocols as a challenge in their first year teaching. For example, Brianna was not familiar with the physical aspects of the school. She said, “Someone … [should] show you around the school … show you where things are." She also said that she would have appreciated being directed to “someone you can go to talk to when you're having trouble.” Mark indicated he was unfamiliar with important school policies. “I didn’t find out about the … software grading system until the second report card. I was actually doing everything manually until my second reporting.” In addition, he stated, “I didn’t have anybody come up to me and talk to me about school policy for example and the expectations.” Mark suggested, “I think there should be a checklist or something for first year teachers, given by the principal and administration saying, ‘Okay, this is what new teachers should be aware of.'”

Successes and challenges with first year teaching: Teaching workload. Both Brianna and Mark described the major challenge of their first year as teachers as learning how to manage their workload. Brianna said, “Well, doing my internship I knew it [being a first year teacher] wasn’t going to be easy. I knew that I was going to have to work on time management, because I have a family … I just knew it wasn’t going to be easy.” Similarly, Mark stated, “I knew it was going to be busy… [Teaching] is a stressful job.” Although both new teachers had anticipated a heavy workload, they were each somewhat surprised by the reality of being a first year teacher. In Brianna’s case, she found that although she had overestimated the amount of work she would have to do, she was still working long hours. Brianna explained that teaching was not as hard she thought it was going to be. According to Brianna,

At the beginning, I was going in a lot in the evenings, and I learned to manage my time better, so I go in now at eight and a leave at five every night. Then I go in Sunday evening. (interview, April, 2007)

In contrast, Mark found that he had underestimated the workload and said, “I knew it was [going to be] busy—I just didn't realize it would be this busy.” He explained, “By busy, I mean time-consuming. You spend your evenings correcting, your weekends at school. This is Sunday, and I’m thinking about going in tonight. Just to get things planned.” Both new teachers found that having students with diverse needs, and a lack of resources regardless of type of resource (e.g., personnel, time, and material) added to their workload. Mark classified his workload as manageable “as long as you have really good organization skills.” Mark further explained that he is “a very organized person” but that without good organizational skills and the help of his educational assistant, the workload “wouldn't be manageable.” Brianna classified her workload as a first year teacher as “very high” and, although she too found the work manageable, she advised that:

You do have to make some sacrifices. I stay an extra hour each day and sometimes more. I don't take all my coffee breaks. I don't usually come home for lunch. I live maybe two blocks from the school and I wasn't coming home for lunch because I wanted to see my family after work and I didn't want to have to go back into the school. (interview, April, 2007)

Successes and challenges with first year teaching: Teaching is rewarding. Mark and Brianna found that teaching was rewarding and that the rewards they received, although different, contributed to their success as a first year teacher. Brianna thought that her biggest reward was seeing evidence of her students’ learning. Brianna commented that, “The best thing is just seeing the growth in the students. I was so excited at the second report card testing all the kids and realizing I’m doing my job and they are learning.” She further stated, “I am pretty proud of my accomplishments.” For Mark, he found the autonomy of being a teacher with his own classroom extremely fulfilling. Mark stated, “I like the autonomy … I like the independence that teaching brings. You know you have curriculum to teach but it's up to you how you want to teach it.”

Aboriginal Concept of Community and Neophyte Aboriginal Teachers

To analyze the findings, we directed our attention to the Aboriginal worldview where the “concept of self is rooted in the context of community and place” (Wilson, 2001b, p. 91). Within Aboriginal cultures, relationships are viewed as pervasive, profound, and reciprocal in nature (Brayboy & Maughan, 2009). From an Aboriginal perspective, a person cannot survive in isolation of others (Kainai Board of Education et al., 2004). This statement attests to the overall importance placed on family, community, relationships, and group wellness. The Aboriginal family encompasses the input of parents, caregivers, Elders, grandparents, aunt, uncles, cousins, and community members. Networking among these members results in intimate bonding, ensuring the protection, survival, and prosperity of all those within the social circle. For Aboriginal peoples, family is about extended biological and social connections made with people within the community. This concept of community can be applied to the successes and challenges that neophyte Aboriginal teachers expressed within this research. However, this Aboriginal community-approach toward assisting new teachers not only supports beginning Aboriginal teachers, but also all beginning educators regardless of ethnicity.

As a part of the Aboriginal worldview, education needs to be community based, incorporating generosity, sharing, and trust embodied by all teachers and educational leaders (Masai, Randall, Rowe, & Waring, 2004). As applicable to this study, school systems need to increase the hospitality they extend to their new teachers. Such a welcoming environment involves a complete sharing of knowledge, ideas, and resources among all teachers all the time. This community-oriented action aids in addressing large workloads, of which the participants spoke. In addition, physically, the school needs a hospitable gathering place for its community of teachers. Within the confines of a comfortable staff room or workroom, new and experienced teachers can meet for both social and professional reasons. This physical community space should also be used to celebrate the accomplishments of its newest teaching members, a point that did not surface in the data. Such a community space should embody an atmosphere of safety and encourage new teachers to share their fears and concerns with fellow community members. In turn, a healthy school community nurtures the sharing of resources, dialogue, successes, and challenges.

Understanding the community aspect of the Aboriginal worldview is akin to knowing that collectivity is more important that individualism. In turn, cooperation, collaboration, group effort, and group rewards have a key role in healthy communities (Kanu, 2011). Part of this school-wide support could include opportunities for mentoring, peer coaching, and team-teaching. In order to nurture trustful and valuable mentor-mentee teacher relationships, time needs to be allocated within the school day to foster and strengthen respectful, trustful mentorship between new and veteran teachers within the school. School-wide support for new teachers could also involve a reduction of teaching responsibilities, at least during the first year of teaching within the school community. As a final point, new teachers should be provided with professional and social opportunities to learn about the school community and its local members. Supporting the strength of one teacher is synonymous to supporting the strength of the entire staff and entire school system. Such a statement aligns with the Aboriginal worldview of interconnected wholeness.

The concept of community extends beyond the walls of the school. For example, community support is embodied through assistance provided by Teacher Federations, which should be readily available to assist beginning teachers in answering potential questions and addressing teacher concerns. To help fulfill emotional and spiritual needs of new teachers, social networking among new teachers and experienced teachers needs to include formal and informal orientations and invitations to events outside the school community. Members from outside the school community also need to play their role in welcoming new teachers to community events. More specifically, the educational leaders of the community, such as the school principal and teachers within the school, could introduce newlyinducted teachers to members of the school community (e.g., parents, community members, and local businesses) and support neophyte teachers in creating outside-of-school contacts, which are needed to sustain work-life balance.

Discussion, Implications, and Limitations

Interview participants spoke at length about how they were inspired to become teachers by familial role models. Brianna also described the delivery of a Bachelor of Education program in a community close to her home as being a significant motivator to become a teacher. These motivations reinforce the overall importance that Aboriginal peoples place on family and community. Survey participants were motivated to become teachers because of altruistic reasons such as “wanting to make a difference” and “wanting to work with young people.” Previous research by Sinclair (2008) identified that the factors that attach people to the teaching profession are commonly based on gender, ethnicity, and socioeconomic groups, with the top motivating factors being the desire to work with students and the desire to make a difference. Other research has demonstrated that Aboriginal teachers identified some similar motivating factors as non-Aboriginal teachers identified such as a passion for teaching and a view that teaching is a calling (St. Denis, 2010). However, none of the participants in the survey or interview portion of this study stated that they entered the teaching profession to share their Aboriginal identity and/or to be an Aboriginal role model. Furthermore, unlike St. Denis’s (2010) study, few of the participants in this study referred to the need for more Aboriginal teachers in the classroom. However, concluding that these factors were therefore unimportant to the Aboriginal teachers in this study is likely erroneous. It is much more likely these results flow from the semi-structured and survey methodology used in this study, which prevented deeper conversations on these specific topics.

Many of the Aboriginal survey respondents identified difficulties in obtaining employment within the teaching profession. This finding reflects similar results in the larger program of research related to this study (Hellsten, Ebanks, & Lai, 2009). In order to enhance employability, Aboriginal participants in this study and beginning teachers in the larger research study engaged in substitute teaching (Hellsten, Ebanks, & Lai, 2009). Similar to the survey respondents, one interview participant of this study stated, “It’s not what you know, it’s who you know.” Furthermore, both interview participants stated they believed that they were able to find term positions due to their previously established relationships. In addition, Brianna believed that the cultural aspects of the education she received as a student in the North helped prepare her for her position. There are practical implications of these findings. First, there is value in delivering education programs at community sites in terms of potential student recruitment, beginning teacher preparedness, and future employment opportunities. Second, internship placements are vitally important to future employability. Whenever practical, education students should be supported in finding appropriate internship placements in communities near to where they may consider future employment. This point may mean that education programs will need to reconsider how internship supervision/facilitation is conducted and may require a move towards more technologically driven facilitation methods.

Because of the underrepresentation of Aboriginal teachers in schools and the need for additional Aboriginal teacher role models, it also seems vital to provide additional supports to help Aboriginal beginning teachers successfully find employment. According to our findings, potential opportunities that may be useful in Aboriginal preservice teacher education include workshops on band-operated schools, networking with other Aboriginal educators and in-school teachers, and seminars on how to apply for substitute teaching contracts. Teacher education programs could also set up peer-to-peer mentorships (Preston, Ogenchuk, & Nsiah, 2011) that alumni could access once in the teaching profession. Such mentorships would mean that new teachers could call upon the previously established relationships that they developed with their peers during their Bachelor of Education programs. Since trust will likely already have been established in these peer-mentorship relationships, such supports have great potential to be of value.

The interview participants in this study also referenced their family, especially family members who are teachers and coworkers, as major sources of support. This finding aligns with the importance placed on family, community, and relationship in the Aboriginal worldview (Kainai Board of Education et al., 2004) as well as the results of our larger research study of beginning teachers in Saskatchewan (Hellsten et al., 2007). In terms of successes, Brianna and many of the survey participants commented on the sense of personal satisfaction they experienced from teaching, especially when they could observe student learning in action. They also noted the importance of relationships and working as part of a community of teachers. For others, including Mark and several of the survey participants, the autonomy of teaching was extremely meaningful to them and they enjoyed having their own classrooms. In one particular case, a survey participant noted her appreciation for autonomy, which resulted in the freedom to teach students culturally relevant practices such as beading.

Many of the challenges that neophyte Aboriginal teachers identified in this study are similar to those identified by other studies of beginning teachers (McIntyre, 2004; OCT, 2003; O’Neill, 2004) as well as studies of Aboriginal educators (St. Denis, 2010) and Aboriginal beginning teachers working in band-controlled schools (Wimmer et al., 2009). These challenges include feeling overwhelmed by the demands of the profession and feeling pressured by the significant workload. Other issues included a lack of personal and professional supports, and a lack of resources in addressing students’ diverse learning needs. Wimmer et al., (2009) also identified four unique challenges for Aboriginal teachers teaching in band-controlled schools including challenges stemming from a “pervasive culture of poverty”; “educational disadvantage and scarcity of resources”; “the complex dynamics of small, close‐knit communities”; and the pressures associated with working “in an educational environment that is often highly politicized,” and seldom stable or secure (Wimmer et al., 2009, p. 831). Although there appears to be some commonalities between the experiences of beginning Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal teachers, future research that focuses specifically on the experiences of Aboriginal beginning teachers is warranted to extend the depth of the conversation and explore the potential for specific cultural challenges and successes.

Mentoring was a topic addressed by the neophyte Aboriginal teachers in this study. Over half of the survey participants responded that they had a mentor. The two Aboriginal interview participants in this study also identified the importance of securing trustful mentors or guides. For both participants, these mentoring relationships were ones they had established on their own (i.e., through an unassigned mentor as neither participant had been connected to a mentor through any formal program). These results parallel findings of earlier research on beginning teacher mentorship (Hellsten, Prytula, Ebanks, & Lai, 2009; Wimmer et al., 2009) and stress the importance of relationship in the induction of new teachers. Unfortunately, neither interview participant stated if their mentor was of Aboriginal ancestry. Future research should more closely examine the impact of culture on mentorship as one survey participant specifically suggested that having access to an Elder and an Aboriginal mentor would have been a welcome source of support.

A key challenge that surfaced within the interviews and was threaded throughout the survey data pertained to the lack of unit plans and curricular documents available for first year teachers. Participants in this study spent much time and effort looking for resources, creating planning units, and deciphering curricular documents, even though their education programs provided experiences in these areas of teaching. This finding aligns with past research that asserts that many new teachers are “lost at sea” when confronting the complexities of curriculum and unit planning (Kauffman, Johnson, Kardos, Liu, & Peske, 2002, p. 273). Additional research highlights that new teachers feel ill-prepared for the planning that is expected of them during their first year of teaching (Graff, 2011). Because research suggests that effective professional learning communities are vehicles for effective teacher induction (Prytula, Makahonuk, Syrota, & Pesenti, 2009), incorporating professional learning communities into schools may be a source of support and mentorship for new teachers specifically with regard to curricular and planning issues.

Understanding the successes and challenges faced by beginning Aboriginal teachers is the first step toward updating research-driven changes to teacher preparation programs. Such changes include a greater focus on how to plan quality lessons and units in a timely fashion, how to teach in classrooms with students who have specialized learning needs, and how to incorporate Aboriginal content and localized ways of knowing into lessons. Instructors of Bachelor of Education programs may consider incorporating more unit plan constructions into their courses. On a volunteer basis, these unit plans could then be stored in an e-library, sorted by grade and subject, and accessible to all teachers in the field. Bachelor of Education programs should also provide accentuated training on how to teach in classrooms with students who have specialized learning needs including how to create individualized learning plans, how to work successfully with educational assistants, and how to acquire sound pedagogy aimed at promoting inclusive, safe, and successful classroom environments.

One of the gaps identified in our research is the need to provide Aboriginal beginning teachers with more support in understanding the politics of band-operated schools. Besides one article focusing on the experiences of beginning Aboriginal teachers in band-operated schools (Wimmer et al., 2009), we have found there to be a lack of educational resources that discuss the potential differences between provincially funded schools and band-operated schools from a practical perspective and aimed for the teacher. Potential areas of stress for teachers in band-operated schools include the politics and governance of band-operated schools, conflicts in band schools, salary grid differences, reduced budgets, curricular differences, and limits to educational programming (Carr Stewart, Marshall, & Steeves, 2011). Future research needs to explore these differences further in order to provide students with the necessary tools to be successful teachers in band-operated schools.

As part of a larger program of work, this study is limited by the fact that three of the authors are not Indigenous scholars and that we all come from the privileged place of academia. This study is also limited by the methodology utilized to study the entire group of beginning teachers. Included in the methodological limitations was our use of survey and semi-structured interviews, which restricted our ability to inquire into the potential effect of culture on Aboriginal beginning teachers’ motivations to be a teacher or other related constructs. Similarly, we encourage researchers to consider carefully the use of surveys and quantitative data in Indigenous contexts and to ensure that their methodology does not contraindicate Indigenous paradigms. We were further limited by the decontextualizing and fragmenting of the data that occurred through the thematic analysis (Kovach, 2010). It is also possible that as outsider interviewers, we may have been lacking the relational factor— that is “With more trust, there is the likelihood of deeper conversations, and consequently the potential for richer insights to the research question” (Kovach, 2010, p. 46). Future research studies exploring Aboriginal neophyte teachers should be centered in Indigenous methodologies, conducted using culturally appropriate and sensitive instruments, and initiated following appropriate preparation including attention paid to interpersonal and community relationships (e.g., visiting community and reciprocity to community and participants),(Kovach, 2010; Kuokkanene, 2010).

Conclusion

Although this study was an attempt to highlight the voices of a small sample of Aboriginal beginning teachers, we now have as many questions as answers. We would like to recreate this study, using Indigenous research methodologies such as talking circles or interviews to focus purposefully on the experiences of ATEP graduates who are employed at provincial or band-operated schools in Saskatchewan. Such a study could celebrate successes, provide solutions to common challenges, and be the impetus for potential policy and programming change at teacher education institutions.

References

Absolon, K. (2011). Kaandossiwin: How we come to know. Halifax, NS: Fernwood.

Absolon, K., & Willett, C. (2004). Aboriginal research: Berry picking and hunting in the 21st century. First Peoples Child and Family Review, 1(1), 5–17.

Absolon, K., & Willett, C. (2005). Putting ourselves forward: Location in Aboriginal research. In L. Brown & S. Strega (Eds.), Research as resistance: Critical, Indigenous and anti-oppressive approaches (pp. 97–126). Toronto, ON: Canadian Scholar’s Press.

Angelle, P. S. (2006). Instructional leadership and monitoring: Increasing teacher intent to stay through socialization. NASSP Bulletin, 90(4), 318–334.

Atleo, E. R. (2004). Tsawalk: A Nuu-chah-nulth worldview. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

Ball, J. (2004, Spring). First Nations Partnership Programs: Incorporating culture in ECE training. The Early Childhood Educator 19(1), 1–5. Retrieved from http://web.uvic.ca/fnpp/FNPP.pdf

Battiste, M. (2008). Research ethics for protecting Indigenous knowledge and heritage: Institutional and researcher responsibilities. In N. K. Denzin, Y. S. Lincoln, & L. T. Smith (Eds.), Handbook of critical and Indigenous methodologies (pp. 497–509). Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.

Botha, L. (2011). Mixing methods as a process towards indigenous methodologies. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 14(4), 313–325.

Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

Brayboy, B. M. J., & Maughan, E. (2009). Indigenous knowledge and the story of Bean. Harvard Educational Review, 79(1), 1–21.

Canadian Teachers’ Federation and Canadian Council on Learning (2010). Toronto, ON:ctffce. Retrieved from http://www.ctffce.ca/Documents/BulletinBoard/ABORIGINAL_Report2010_EN_re-WEB_Mar19.pdf

Carr Stewart, S., Marshall, J., & Steeves, L. (2011). Inequity of education financial resources: A case study of First Nations and provincial education funding in Saskatchewan. McGill Journal of Education, 46(3), 363–377.

Chilisa, B. (2012). Indigenous research methodologies. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Creswell, J. W., Plano Clark, V. L., Gutmann, M., & Hanson, W. (2003). Advanced mixed methods research designs. In A. Tashakkori & C. Teddlie (Eds.), Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research (pp. 209–240). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Croninger, R. G., King Rice, J., Rathbun, A., & Nishio, M. (2007). Teacher qualifications and early learning: Effects of certification, degree, and experience on first-grade student achievement. Economics of Education Review, 26(3), 312–324. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2005.05.008

Denzin, N. K. (1989). Interpretive interactionism. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Fine, M., Weis, L., Wesson, S., & Wong, L. (2003). For whom? Qualitative research, representations, and social responsibilities. In N.K. Denzin & Y.S. Lincoln (Eds.). The landscape of qualitative research (pp. 167–207). Thousand Oakes, CA: Sage.

Friesen, D., & Orr, J. (1996). Northern Aboriginal teachers’ voices: A constellation of stories. Regina, Saskatchewan School Trustee Association. SSTA Research Centre report #96-15.

Graff, N. (2011). “An effective and agonizing way to learn” : Backwards Design and new teachers’ preparation for planning curriculum. Teacher Education Quarterly, 38(3), 151–168.

Greenwood, M., de Leeuw, S., & Fraser, T. (2007). Aboriginal children and early childhood development and education in Canada. Canadian Journal of Native Education, 30(1), 5–18.

Hardes, J. (2006). Retention of Aboriginal students in postsecondary education. Alberta Counsellor, 29(1) 28–33.

Hellsten, L. M., Ebanks, A., & Lai, H. (2009, January). Employed or not employed? A two-year examination of Saskatchewan beginning teachers’ experiences of seeking and obtaining employment. Poster presentation at the Hawaii International Conference on Education, Honolulu, Hawaii.

Hellsten, L. M., & Prytula, M. P. (2011). Why teaching? Motivations influencing beginning teachers’ choice of profession and teaching practice. Research in Higher Education, 13, 1-19. Retrieved from http://www.aabri.com/manuscripts/11882.pdf

Hellsten, L. M., Prytula, M., Ebanks, A., & Lai, H. (2009). Teacher induction: Exploring beginning teacher mentorship. Canadian Journal of Education, 32(4), 703–733.

Hellsten, L. M., Prytula, M., Dueck, G., Karlenzig, B., Martin, S., & Reynolds, C. (2007, May). Becoming a teacher: What supports and resources do beginning teachers value? Presentation at the meeting of the Canadian Society for the Study of Education, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.

Ingersoll, R. M. (2001). A different approach to solving the teacher shortage problem. Teaching Quality Policy Briefs. Center for the Study of Teaching and Policy. Retrieved from www.depts.washington.edu/ctpmail.Briefs.html

Ingersoll, R. M., & Smith, T. M. (2004). Do teacher induction and mentoring matter? NASSP Bulletin, 88(638), 28–40.

Kainai Board of Education, Métis Nation of Alberta, Northland School Division, & Tribal Chiefs Institute of Treaty Six (2004). Aboriginal Studies 10: Aboriginal perspectives. Edmonton, AB: Duval House.

Kanu, Y. (2011). Integrating Aboriginal perspectives into the school curriculum: Purpose, possibilities, and challenges. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Kauffman, D., Johnson, S. M., Kardos, S. M., Liu, E., & Peske, H. G. (2002). “Lost at Sea”:

New teachers’ experiences with curriculum and assessment. Teachers College Record 104(2), 273–300.

Kelley, L. M. (2004). Why induction matters. Journal of Teacher Education, 55(5), 438–448.

Khamis, M. (2000). The beginning teacher. In S. Dinham & C. Scott (Eds.), Teaching in context (pp. 1–17). Camberwell: Australian Council of Educational Research.

Kovach, M. (2009). Indigenous methodologies: Characteristics, conversations, and contexts. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Kovach, M. (2010). Conversational method in Indigenous Research. First Peoples Child & Family Review, 5(1), 40–48.

Kuokkanene, R. (2010). The responsibility of the academy: A call for doing homework. Journal of Curriculum Theorizing, 26(3), 61–74.

Legare, L., Pete-Willett, S., Ward, A., Wason-Ellam, L., & Williamson, K. (1998). Diverting the mainstream: Aboriginal teachers reflect on their experiences in the Saskatchewan provincial school system. Report presented to Saskatchewan Education. Regina, SK. Retrieve from http://www.education.gov.sk.ca/diverting-mainstream

Le Maistre, C. (2000). Mentoring neophyte teachers: Lessons learned from experience. McGill Journal of Education, 35(1), 83–87.

Maciejewski, J. (2007). Supporting new teachers: Are induction programs worth the cost? District Administration, 43(9), 48–52.

Martin, L. A., Chiodo, J. J., & Chang, L. (2001). First year teachers: Looking back after three years. Action in Teacher Education, 23(1), 55–61.

Masai, J., Randall, A., Rowe, D., & Waring, F. (2004). Aboriginal leaders resistance and education. In F. Adu-Febriri (Ed.), First Nations students talk back: Voices of learning people (pp. 145–165). Victoria, BC: Camosun College.

McIntyre, F. (2004, December). New teachers thriving by third year. Professionally Speaking. Retrieved from http://professionallyspeaking.oct.ca/december_2004/reports.asp

McCormack, A., & Thomas, K. (2003). Is surviving enough? Induction experiences of beginning teachers within a New South Wales context. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 31(2), 124–138.

McPherson, S. (2000). From practicum to practice: Two beginning teachers’ perceptions of the quality of their preservice preparation. (Unpublished master’s thesis). Queen’s University, Kingston, ON.

Moir, E., & Gless, J. (2001). Quality induction: An investment in teachers. Teacher Education Quarterly, 28(1), 109–114.

Morse, J. M. (1991). Approaches to qualitative-quantitative methodological triangulation. Nursing Research, 40(2), 120–123.

Mueller, R., Carr-Stewart, S., Steeves, L., & Marshall, J. (2011). Teacher recruitment and retention in select First Nations schools. in education, 17(3). Retrieved from http://ineducation.ca/article/teacher-recruitment-and-retention-select-first-nations-schools

Nolais, J. (2012, February 6). Teacher retention: A growing Alberta problem. Metro Calgary. Retrieved from http://metronews.ca/news/calgary/37495/teacher-retention-a-growing-alberta-problem/

O’Neill, L. M. (2004). Support systems: Quality induction and mentoring programs can help recruit and retain excellent teachers and save money. Threshold, Spring, 12–15.

Ontario College of Teachers (OCT) (2003). New teacher induction: Growing into the profession. Toronto, ON: Author.

Preston, J. P., Cottrell, M., Pelletier, T. R., & Pearce, J. V. (2012). Aboriginal early childhood education in Canada: Issues of context. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 10(1), 3–18.

Preston, J. P., Ogenchuk, M. J., & Nsiah, J. K. (2011). Peer mentorship: Narratives of PhD attainment. In E. Ralph & K. D. Walker (Eds.), Adapting mentorship across the professions: Fresh insights and perspectives (pp. 123–138). Calgary, AB: Temeron/Detselig Enterprises.

Prytula, M. P., Hellsten, L. M., & McIntyre, L. J. (2010). Perceptions of teacher planning time: An epistemological challenge. Current Issues in Education, 13(4), 1–30.

Prytula, M., Makahonuk, C., Syrota, N., & Pesenti, M. (2009).Successful teacher induction through communities of practice. Saskatoon, SK: Dr. Stirling McDowell Foundation for Research into Teaching.

Rogers, D. L., & Babinski, L. M. (2002). From isolation to conversation: Supporting new teachers' development. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Ronfeldt, M., Loeb, S., & Wyckoff, J. (2013). How teacher turnover harms student achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 50(1), 4–36.

Russell, T., McPherson, S., & Martin, A. K. (2001). Coherence and collaboration in teacher education reform. Canadian Journal of Education, 26(1), 37–55.

Sinclair, C. (2008). Initial and changing student teacher motivation and commitment to teaching. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 36(2), 79–104.

Simurda, S. J. (2004). The urban/rural challenge: Overcoming teacher recruitment and retention obstacles faced by urban and rural school districts. Threshold, Spring, 22–25.

Smith, L. T. (2012). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and Indigenous peoples (2nd ed.). London, England: Zed Books.

Snyder, J. F., Doerr, A. S., & Pastor, M. A. (1995). Perceptions of preservice teachers: The job market, why teaching, and alternatives to teaching. Slippery Rock, PA: Slippery Rock University.

Statistics Canada. (2008). Aboriginal identity population by age groups, median age and sex, 2006 counts from Canada, provinces and territories. Retrieved from http://www12.statcan.ca/english/census06/data/highlights/Aboriginal/pages/Page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo=PR&Code=01&Table=1&Data=Count&Sex=1&Age=1&StartRec=1&Sort=2&Display=Page

Statistics Canada. (2011, December 7). Population projections by Aboriginal identity in Canada. The Daily. Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/111207/dq111207a-eng.htm

St. Denis, V. (2010). A study of Aboriginal teachers’ professional knowledge and experience in Canadian public schools.

St. Denis, V. (2011). Silencing Aboriginal curricular content and perspectives through multiculturalism: “There are other children here.” Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies, 33(4), 306–317. doi: 10.1080/10714413.2011.597638

St. Denis, V., Bouvier, R., & Battiste, M. (1998, October). Okiskinahamakewak – Aboriginal teachers in Saskatchewan’s publicly funded schools- Responding to the flux. Regina, SK: Saskatchewan Education Research Networking Project. Retrieved from http://www.usask.ca/education/people/battistem/okiskinahamakewak.pdf

Steele, K. (2011). The road ahead for higher ed. Toronto, ON: Academica Group. Retrieved from http://2011.pseweb.ca/cms/wp-content/files/PSEWeb-2011-Trends.pdf

Struthers, R. (2001). Conducting sacred research: An indigenous experience. Wicazo Sa Review, 16(1), 125-133. Retrieved from http://nursing.ucla.edu/workfiles/CAIIRE/Articles/conducting%20sacred%20research.pdf

Suydam, J. (2002, May 29). Teacher shortage worsening in Texas: More uncertified educators will be needed to fill the gap, research shows. Austin American Statesman, p. A1.

Villani S. (2002). Mentoring programs for new teachers: Models of induction and support. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Voke, H. (2002, May). Understanding the teacher shortage. ACSD InfoBrief, Issue 29, 1–17.

Watts Hull, J. (2004). Filling in the gaps: Understanding the root causes of the teacher shortage can lead to solutions that work. Threshold, Spring, 8–12, 15.

Weber-Pillwax, C. (2001). Coming to an understanding: A panel presentation. What is Indigenous Research? Canadian Journal of Native Education, 25(2), 166–174.

Wilson, S. (2001a). What is an Indigenous research methodology? Canadian Journal of Native Education, 25(2), 175–180.

Wilson, S. (2001b). Self-as-relationship in Indigenous research. Canadian Journal of Native Education, 25(2), 91–92.

Wilson, S. (2008). Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods. Halifax, NS: Fernworood.

Wilson, S., & Wilson, P. (1998). Relational accountability to all our relations: Editorial. Canadian Journal of Native Education, 22(2), 155–158.

Wimmer, R., Legare, L., Arcand, Y., & Cottrell, M. (2009). Experience of beginning Aboriginal teachers in band-controlled schools. Canadian Journal of Education, 32(4), 817–849.

Wotherspoon, T. (2008). Teachers’ work intensification and educational contradictions in Aboriginal communities. The Canadian Review of Sociology, 45(4), 389–418.

Endnotes

[1] Although the word Indigenous is becoming the most politically accurate term when discussing First Nation, Métis, and Inuit peoples, we have used the term Aboriginal for the following reasons. First, Saskatchewan Government documents pertaining to education tend to use the term Aboriginal. Second, our study refers to Aboriginal neophyte teachers in part because these students are graduates of an Aboriginal Teacher Education Program and Aboriginal is the term commonly associated with the program and used by faculty and students. Despite potential confusion, if an author we have cited has used the term Indigenous in their work, we have left the term unchanged in order to be respectful to the author's voice and faithful to their work.

[2] There is also a parallel call to recruit and retain Aboriginal teachers in First Nations schools (Mueller, Carr-Stewart, Steeves, & Marshall, 2011).

[3] Aboriginal education programs in Saskatchewan include the Indian Teacher Education Program (ITEP), Saskatchewan Urban Native Teacher Education Program (SUNTEP), and Northern Teacher Education program (NORTEP). In order to participate in ITEP, applicants must self-identify as having First Nations ancestry; SUNTEP applicants must self-identify as having Métis ancestry, and the vast majority of NORTEP participants have First Nations, Métis or Inuit ancestry. For a detailed description of these programs see Wimmer et al., 2009.

[4] First Nations schools are also referred to as band-operated schools and are schools funded outside of the provincial K-12 system.

[5] The comments from the interviews with Brianna and Mark (pseudonyms) are woven into the paragraphs below. The interviews with Brianna and Mark were conducted in April of 2007.

[6] Throughout this article, pseudonyms are inserted in place of real names.